Baltringer Haufen

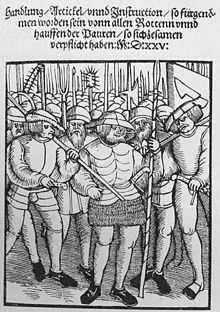

The Baltringer Haufen (also spelled Baltringer Haufe, German for Baltringen Band, Baltringen Troop or Baltringen Mob) was prominent among several armed groups of peasants and craftsmen during the German Peasants' War of 1524-1525. The name derived from the small Upper Swabian village of Baltringen, which lies approximately 25 kilometres (16 mi) south of Ulm in the district of Biberach, Germany. In the early modern period the term Haufe(n) (literally: heap) denoted a lightly organised military formation particularly with regard to Landsknecht regiments.[1]

Formation of the Baltringer Haufen

According to the account of a nun from nearby Heggbach Abbey, local peasants assembled and conferred in an inn at Baltringen for the first time on Christmas Eve 1524.[2] From then on regular meetings took place,[3] the number of attendants reaching 80 at the beginning of February 1525. Whereas in other regions the peasants met and discussed at markets, in Baltringen this occurred during the Fastnacht (Carnival) season, which aided conspirative gatherings in that peasants were wont to travel from village to village for eating and drinking, giving them the opportunity to discuss matters at hand.[4] Drawing participants from the whole region, these meetings eventually became more regular, taking place every Tuesday with the number of attendants gradually swelling to 400, at which point meetings were beginning to be held in open space, the Baltringer Ried, a boggy area (now drained) just outside the village of Baltringen. On 3 or 4 February 1525 the peasants chose as their representative Ulrich Schmid (Huldrich Schmid), a blacksmith from the nearby village of Sulmingen, who hesitantly accepted the task.[5]

The peasants' demands

Soon the authorities learnt of these meetings and representatives of the Swabian League, an association of Imperial cities, principalities, both ecclesiastic and secular, and knights, contacted the Baltringer Haufen. While the Imperial cities advocated negotiations and mediation, the princes pleaded for a strategy of violence. The Imperial League chose as their representatives Johann von Königsegg, Wilhelm von Köringen and the mayor of Ulm, Ulrich Neidhardt, who met the peasants in the Baltringer Ried on 9 February 1525 asking them to write down their complaints. One week, later, on 16 February 1525, in the presence of between 10000 to 150000 peasants,[6] a list of complaints was delivered in written form to the representatives of the Swabian League: more than 300 written complaints, one for each village.[7]

The main complaint made by the Baltringen peasants was the fact that they were serfs. They also requested the reduction of rents and annual duties in kind, as well as the abolition of death duty. Furthermore, they asked not to be burdened with socage any longer and to be allowed to utilise timber from the forests. They also opposed the little tithe but were prepared to pay great tithe in order to provide for the upkeep of their respective local priest.[8]

Following the reply by of the Swabian League, delivered on 27 February 1525, Ulrich Schmid justified the peasants' demands by referring to the "Divine Law",[9] the concept of which, as opposed to the Traditional (Old) Law, meaning the traditional legal norms, offered a completely new perspective in the legal relationship between lord and peasant. The political order had to be compared with the divine will as manifested in the Bible. By doing so, the peasant challenged the whole concept of traditional law. Ulrich Schmid, the representative of the Baltringer Haufen, rejected the traditional legal process through the Imperial Chamber Court to solve the complaints of the peasants. Theologians had to decide as to whether the peasants' demands were justified.[10] Ulrich Schmid proposed that a group of men, learnèd and steeped in Christian lore, should decide what constitutes this "Divine Law". The representatives of the Swabian League concurred and announced that they would also pray to God in order to ensure that these learnèd men would be chosen.[11] Ulrich Schmid hoped that regarding this issue he would be helped in Memmingen[12] where he managed to recruit Sebastian Lotzer, a journeyman furrier, to take on the role of clerk to the Baltringer Haufen. On 28 February 1525, the Baltringer Haufen officially declared its formation to the Imperial city of Ehingen in a missive composed by Lotzer. The wording of this missive seems to imply that there may already have been contacts between Lotzer, who resided in Memmingen and had been active as clerk to the Memminger peasants, and Schmid well before the end of February 1525.[13]

Formation of the Christian Alliance

On the initiative of Lotzer and Schmid, representatives of three peasants' armies, the Baltringer Haufen, the Allgäuer Haufen and the Seehaufen (based near Lake Constance), both of which had formed shortly after the Baltringer Haufen, met in Memmingen where they decided to merge and, on 6 March 1525, formed the Christian Association.[14] In a letter they informed the Swabian League of the association's formation and declared their intention not to use violence while asking the League to refrain also from violence. Based on the demands by the Baltringer Haufen and with the probable participation of the Memmingen preacher Christoph Schappeler the association worked out the most famous document of the German Peasants' War, the Twelve Articles, in which the idea of "Divine Law" was combined with the peasants' demands. On 7 March 1525 Sebastian Lotzer, the Baltringers' clerk, also penned the Federal Ordinance (Bundesordnung), the Christian Association's draft constitution.[15] On 15 and 16 March 1525, during further deliberation of the assembled peasants at Memmingen, a list of persons, who were supposed to evaluate and examine the peasants' wishes, demands and aims, and were to ascertain what actually constitutes "Divine Law" was published. It contains 14 names amongst which were well-known reformers such as Martin Luther, Philipp Melanchthon and Huldrych Zwingli as well as Archduke Ferdinand of Austria and Frederick of Saxony. The Swabian League rejected the list. It seems that this list was the main bone of contention in the negotiations between the representatives of the Swabian League and the peasants.[16] A second, amended list was published on 20 March 1525 and presented to the Swabian League in Ulm on 24 March 1525. The names on this list were supposed to be less contentious, comprising persons of more local and regional importance.[17] The following day, a new proposal, developed by the mayors of Kempten and Ravensburg, was handed over to the peasants' representatives, containing demands for the dissolutions of the Christian Alliance, the formation of an arbitration court, distancing of the peasants from the idea of "Divine Law" and obedience to the authorities.[18] The peasants were given until 2 April to decide on these counter-demands.[19]

Escalation

The Swabian League had been in conflict with Duke Ulrich of Württemberg for several years. As a consequence, at the beginning of 1525 the troops of the Swabian League commanded by Georg Truchsess von Waldburg (later known as Bauernjörg) were occupied in suppressing an attempt by Duke Ulrich to regain his throne. At the behest of Leonhard von Eck, the Bavarian chancellor and the most influential person within the Swabian League, negotiations with the peasants were to be stalled until the war against Duke Ulrich was successfully concluded, so that the League's troops deployed in this war could be utilised against the peasants.[20] During the second half of March 1525 the Swabian League's military action against Duke Ulrich of Württemberg finally ended which freed forces to intervene in Upper Swabia. In a letter dated 25 March 1525 the Baltringer Haufen complained that soldiers belonging to the Swabian League had started to attack villages. They emphasised again that they demanded nothing but the application of the "Divine Law." The situation escalated after news that troops of the Swabian League, consisting of 8000 footsoldiers and 3000 cavalry,[21] had arrived at Ulm reached the peasants on 26 March 1525. The same day the peasants looted Schemmerberg Castle which was in the possession of the Salem Abbey. The following day, as a reaction to the slaying by troops of the Swabian League of a landlord from Griesingen returning from Memmingen, 8000 enraged peasants stormed and looted, amongst others, Heggbach Abbey, Laupheim Castle, Untersulmetingen Castle and Achstetten Castle, the latter two were also burnt to the ground.[22] The monasteries of Gutenzell, Ochsenhausen, Wiblingen and Marchtal were forced to support the Baltringer Haufen by provisioning the peasants with goods. At the same time intense diplomatic activities by the Upper Swabian cities were instigated in order to prevent a military confrontation between the peasants and the Swabian League by appealing to both parties to refrain from violence. In the end all these efforts were to no avail.[23]

On 31 March 1525 troops of the Swabian League based at Erbach moved towards Dellmensingen in order to loot the village. Even though the commanding office of this detachment, Count Wilhelm von Fürstenberg, had planned to cross the Danube with all his forces, he did not manage to have his artillery traverse the river and due to the boggy terrain the cavalry could not be utilised either. Parts of the Baltringer Haufen, however, had been deployed at Dellmensingen. During the ensuing battle 50 soldiers of the Swabian League lost their lives. Consequently, the attacking troops retreated over the river Danube.[24] Further skirmishes took place near Achstetten, Oberstadion and Zwiefalten during which several villages, after having been looted, were set ablaze by troops of the Swabian League. Following these first unsuccessful attempts to subdue the Baltringer Haufen, Georg Truchsess von Waldburg then turned to face the challenge of the seemingly more threatening peasant army that had formed near Leipheim. During the ensuing battle, the Leipheimer Haufen was utterly defeated on 4 April 1525; their leaders, Hans Jakob Wehe and seven others, were executed by being beheaded the next day.[25] On 10 April 1525 the Swabian League's army under the command of Georg Truchsess von Waldburg departed Leipheim in order to return to Upper Swabia. The next day the army encountered a band of peasants near Laupheim who decided to make a stand on the hill where the local church stood.[26] During the ensuing battle, the army of the Swabian League killed 150 farmers, scattering the survivors into the surrounding forests.[27] This enabled Georg Truchsess von Waldburg to proceed to Baltringen where he arrived on 12 April 1525, accompanied by a force of 400 men. The remaining forces of the Baltringer Haufen between Biberach and Ulm capitulated unconditionally. In spite of orders by the Swabian League, the village of Baltringen was not burnt to the ground.[28]

Aftermath

Some units (Fähnlein) of the Baltringer Haufen, however, took part in the Battle of Leipheim on 14 April 1525, whereas others had joined forces with the Seehaufen and the Allgäuer Haufen and were part of the forces confronted by Georg Truchsess von Waldburg in mid-April 1525 near Weingarten. The army of the Swabian League was clearly outnumbered by the peasants. Georg Truchsess von Waldburg did not dare to attack the Haufen and chose instead to negotiate. This led to the Treaty of Weingarten, a treaty between the Swabian League and the Seehaufen and the Allgäuer Haufen on 17 April 1525.[29] The Swabian League, however, refused the subsequent application of the treaty's terms to the Baltringer Haufen.[30]

After their military defeat, the peasants had to renew their oath of allegiance, followed by a wave of claims for compensation. The peasants form Baltringen were punished particularly severe: even though the village was not put to the torch as ordered by the Swabian League,[31] they had to pay double the punitive damages other villages had to pay.[32] Generally, villages that were thought to have been involved with or sympathetic to the Baltringer Haufen were ordered to pay fines. In Biberach, for example, the Spital, a charitable institution and at the same time a large landowner in Upper Swabia, imposed fines on 684 of its approximately 2400 subjects in 38 villages.[33]

The leaders of the Baltringer Haufen, Ulrich Schmid, Sebastian Lotzer and Christoph Schappeler, managed to save their lives by escaping to Switzerland.[34]

The immediate retribution of the Swabian League consisted of the execution of those leading figures of the uprising it managed to apprehend. Since most of the prominent figures of the Baltringer Haufen had eluded capture, the Swabian League resorted to executing a number of peasants as a deterrent.[35] Yet, even six months later, in September 1525, Hans Burkhard von Ellerbach, the lord of Laupheim, had 14 peasants arrested, two of which were executed by decapitation.[36]

Assessment

The Baltringer Haufen had a major influence on the German Peasants' War in Upper Swabia and beyond. Even though it was not successful in persuading the other Haufen to follow its demand of non-violence and its invocation of the "Divine Law",[37] its leaders nevertheless suggested the merging of the three dominant peasant armies in the region to form the Christian Alliance. The influence and contribution of the Baltringer Haufen is clearly visible in the Twelve Articles and the Federal Ordinance both of which became the most important manifestos of the German Peasants' War.[38] The insurrection failed because the Baltringer Haufen supported a policy of non-violence until the arrival of the troops of the Swabian League and was therefore unprepared for a military conflict. Even though many of the peasants had some military experience and the Baltringer Haufen had artillery at its disposal, they lacked cavalry. What turned out to be even more important, however, was the lack of military and political leaders who were able to survey and assess the situation as a whole and combine the multitude of local complaints into an effective challenge the Swabian League had to reckon with.[39] Differences in opinion between the three Haufen with regards to the Federal Ordinance meant that the Allgäuer Haufen and the Seehaufen did not come to the aid of the Baltringer Haufen once the Swabian League moved its troops against it. The Swabian League was well aware of this disunity.[40] None of the various Haufen seemed to have been generally prepared to operate outside their own region, or come to the assistance of other Haufen under attack, which facilitated the suppression of the insurrection by the troops of the Swabian League.[41] Yet, the peasants' uprising left its marks on Upper Swabia. Following the Treaty of Weingarten, a series of contracts between peasants and their lords was concluded with the result that the situation of the peasants slowly began to change for the better, economically as well as legally.[42] In particular, the living conditions of the serfs began to improve; serfdom was gradually to be phased out over the next centuries.[43]

The Baltringer Haufen remembered

In the basement of Baltringen's town hall two rooms are dedicated to the commemoration of the Baltringer Haufen. The museum, called "Place of Remembrance for the Baltringer Haufen - Peasants' War in Upper Swabia", evolved out of a former single-room museum, called the "Peasants' War Parlour", founded in 1984, following a resolution by the local council, and designed by Franz Liesch. Its purpose was to document the history of the Baltringer Haufen. By doing so, Baltringen became the first place in West Germany to establish a museum dedicated to the Peasants' War. On the 475th anniversary of the events in 1525, the new premises, following a concept designed by Benigna Schönhagen, were opened on 7 April 2000 by Peter Blickle.[44]

See also

References

- ↑ D. W. Sabean, Landbesitz und Gesellschaft am Vorabend des Bauernkriegs, p. 8

- ↑ F. Baumann, Quellen, p. 277.

- ↑ A. Waas, Die Bauern im Kampf um Gerechtigkeit: 1300 - 1525, p. 179

- ↑ J. M. Stayer, The German Peasants’ War and Anabaptist Community of Goods, p. 21

- ↑ Johannes Kesslers Sabbata, p. 173ff.

- ↑ G. Schenk, Laupheim, p. 23; some sources report up to 18000 peasants.

- ↑ Johannes Kesslers Sabbata, p. 323f

- ↑ D. W. Sabean, Landbesitz und Gesellschaft am Vorabend des Bauernkriegs, p. 87f

- ↑ Johannes Kesslers Sabbata, p. 325

- ↑ P. Blickle, Von der Leibeigenschaft zu den Menschenrechten, p. 88f

- ↑ P. Blickle, Die Revolution von 1525, p. 5f

- ↑ Johannes Kesslers Sabbata, p. 326

- ↑ M. Arnold, Handwerker als theologische Schriftsteller, p. 187

- ↑ P. Blicke, Die Revolution von 1525, p. 152

- ↑ G. Seebaß, Artikelbrief, Bundesordnung und Verfassungsentwurf, p. 95

- ↑ R. Stauber, Memmingen: Der Bauernaufstand im Zunfthaus 1525, p. 176

- ↑ P. Blickle, From the Communal Reformation to the Revolution of the Common Man, p. 63

- ↑ W. Zimmermann, Allgemeine Geschichte des Großen Bauernkrieges, p. 150

- ↑ H. Schreiber, Der deutsche Bauernkrieg, p. 29ff

- ↑ C. Greiner, Die Politik des Schwäbischen Bundes, p. 26ff

- ↑ A. Weill, Der Bauernkrieg, p. 179

- ↑ Johannes Kesslers Sabbata, p. 329f

- ↑ P. Blickle, Die Revolution von 1525, p. 173f

- ↑ W. Zimmermann, Geschichte des großen Bauernkrieges, vol. 1, p. 172f

- ↑ H. Brackert, Bauernkrieg und Literatur, p. 103

- ↑ G. Schenk, Laupheim, p. 24

- ↑ Beschreibung des Oberamts Laupheim, p. 85

- ↑ Johannes Kesslers Sabbata, p 332

- ↑ H. Rabe, Reich und Glaubensspaltung, p. 201

- ↑ C. Greiner, Die Politik des Schwäbischen Bundes, p. 80f

- ↑ S. Ott, Oberschwaben, p. 111

- ↑ Beschreibung des Oberamts Laupheim, p. 85

- ↑ D. Stievermann, Geschichte der Stadt Biberach, p. 179

- ↑ G. Franz, Der Deutsche Bauernkrieg, W. Packull, The Origins of Swiss Anabaptism, p. 53;

- ↑ T. Sea, Schwäbischer Bund und Bauernkrieg, p. 150

- ↑ P. Blickle, Gemeinde und Gemeindeverfassung in Laupheim, p. 221

- ↑ A. Waas, Die Bauern im Kampf um Gerechtigkeit: 1300 - 1525, p. 180

- ↑ P. Blickle, Der Bauernkrieg, p. 23; P. Blickle, From the Communal Reformation to the Revolution of the Common Man, p. 99

- ↑ A. Laufs, Rechtsentwicklungen in Deutschland, p. 125

- ↑ G. P. Sreenivasan, The Peasants of Ottobeuren, 1487-1726, p. 40

- ↑ J. M. Stayer, The German Peasants' War and the Rural Reformation, p. 136

- ↑ H. Carl, Der Schwäbische Bund 1488 - 1534, p. 496

- ↑ A. Laufs, Rechtsentwicklungen in Deutschland, p. 129

- ↑ "Erinnerungsstätte Baltringer Haufen". Baltringer Haufen - Freunde der Heimatgeschichte e.V. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

Primary Sources

- Baumann, Franz Ludwig (ed.) (1975), Quellen zur Geschichte des Bauernkriegs in Oberschwaben (repr. ed.), Hildesheim: Olms, ISBN 3-487-05554-6

- Schiess, Traugott (ed.) (1911), Johannes Kesslers Sabbata: St. Galler Reformationschronik 1523-1539, Leipzig: Verein für Reformationsgeschichte

- Schreiber, Heinrich(ed.) (1863), Der deutsche Bauernkrieg. Gleichzeitige Urkunden, Freiburg: Franz Xaver Wangler

Further reading

- Arnold, Martin (1990), Handwerker als theologische Schriftsteller. Studien zu Flugschriften der frühen Reformation (1523 - 1525) (in German), Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, ISBN 3-525-87396-4

- Blickle, Peter (1979). "Gemeinde und Gemeindeverfassung in Laupheim". In Diemer, Kurt. Laupheim (in German). Weißenhorn: Konrad. pp. 219–234. ISBN 3-87437-151-4.

- Blickle, Peter (1998), From the Communal Reformation to the Revolution of the Common Man, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-10770-3

- Blickle, Peter (2002), Die Revolution von 1525 (in German) (4 ed.), München: Ouldenbourg, ISBN 3-486-44264-3

- Blickle, Peter (2006), Der Bauernkrieg. Die Revolution des gemeinen Mannes (in German) (3 ed.), München: C.H. Beck, ISBN 3-406-43313-8

- Blickle, Peter (2006), Von der Leibeigenschaft zu den Menschenrechten. Eine Geschichte der Freiheit in Deutschland (in German) (2 ed.), München: Beck, ISBN 3-406-50768-9

- Brackert, Helmut (2000), Bauernkrieg und Literatur (in German), Leinfelden-Echterdingen: DRW-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-7995-5224-0

- Carl, Horst (1975), Der Schwäbische Bund 1488 - 1534. Landfrieden und Genossenschaft im Übergang vom Spätmittelalter zur Reformation (in German) (1 ed.), Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-00782-3

- Garlepp, Hans-Hermann (1987), Der Bauernkrieg von 1525 um Biberach an der Riss. Eine wirtschafts- und sozialgeschichtliche Betrachtung der aufständischen Bauern (in German), Frankfurt am Main: Lang, ISBN 3-8204-0274-8

- Greiner, Christian (1974), "Die Politik des Schwäbischen Bundes während des Bauernkrieges 1524/1525 bis zum Vertrag von Weingarten", Zeitschrift des Historischen Vereins für Schwaben (in German) 68: 7–94

- Franz, Günther (1977), Der Deutsche Bauernkrieg (in German) (11 ed.), Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, ISBN 3-534-00202-4

- Königlich Statistisch-Topographisches Bureau (Württemberg) (ed.) (1856), Beschreibung des Oberamts Laupheim (in German), Stuttgart: Hallberger

- Kuhn, Elmar (2000), Der Bauernkrieg in Oberschwaben (in German), Tübingen: Bibliotheca Academica Verlag, ISBN 3-928471-28-7

- Laufs, Adolf (1996), Rechtsentwicklungen in Deutschland (in German) (5 ed.), Berlin: de Gruyter, ISBN 3-11-014620-7

- Liesch, Franz (2004), Der Baltringer Haufen (in German), Baltringen: Verein Baltringer Haufen

- Ott, Stefan (1972), Oberschwaben. Gesicht einer Landschaft (in German) (2 ed.), Ravensburg: Maier, ISBN 3-473-43555-4

- Packull, Werner O. (1985), "The Origins of Swiss Anabaptism in the Context of the Reformation of the Common Man", Journal of Mennonite Studies 3: 36–59

- Rabe, Horst (1989), Reich und Glaubensspaltung. Deutschland 1500 - 1600 (in German), München: Beck, ISBN 3-406-30816-3

- Sabean, David Warren (1972), Landbesitz und Gesellschaft am Vorabend des Bauernkriegs. Eine Studie der sozialen Verhältnisse im südlichen Oberschwaben in den Jahren vor 1525 (in German), Stuttgart: Fischer, ISBN 3-437-50161-5

- Schenk, Georg (1976), Laupheim: Geschichte, Land, Leute (in German), Weißenhorn: Konrad, ISBN 3-87437-136-0

- Scott, Tom; Scribner, Robert W. (1991), The German Peasants' War: A History in Documents, Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, ISBN 0-391-03681-5

- Sea, Thomas S. (1975). "Schwäbischer Bund und Bauernkrieg. Bestrafung und Pazifikation". In Hans-Ulrich Wehler (ed.). Der deutsche Bauernkrieg 1524-1526 (in German). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht,. pp. 129–167. ISBN 3-525-36400-8.

- Seebaß, Gottfried (1988), Artikelbrief, Bundesordnung und Verfassungsentwurf. Studien zu 3 zentralen Dokumenten des südwestdeutschen Bauernkriege (in German), Heidelberg: Winter, ISBN 3-533-03987-0

- Sreenivasan, Govind P. (2004), The Peasants of Ottobeuren, 1487-1726. A Rural Society in Early Modern Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-83470-8

- Stauber, Reinhard (2003). "Memmingen: Der Bauernaufstand im Zunfthaus 1525". In Alois Schmid, Katharina Weigand (eds.). Schauplätze der Geschichte in Bayern (in German). München: Beck. pp. 165–183. ISBN 3-406-50957-6.

- Stayer, James M. (1991), The German Peasants’ War and Anabaptist Community of Goods, Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, ISBN 0-7735-0842-2

- Stayer, James M. (2000). "The German Peasants' War and the Rural Reformation". In Pettegree, Andrew (eds.). The Reformation World. London: Routledge. pp. 127–145. ISBN 0-415-16357-9.

- Stievermann, Dietrich (1991), Geschichte der Stadt Biberach (in German), Stuttgart: Theiss, ISBN 3-8062-0564-7

- Waas, Adolf (1976), Die Bauern im Kampf um Gerechtigkeit: 1300 - 1525 (in German) (2 ed.), München: Callwey, ISBN 3-7667-0069-3

- Weill, Alexandre (1847), Der Bauernkrieg (in German), Darmstadt: E. W. Leske

- Zimmermann, Wilhelm (1842), Allgemeine Geschichte des großen Bauernkrieges (in German) 2, Stuttgart: Franz Heinrich Köhler

- Zimmermann, Wilhelm (1856), Geschichte des großen Bauernkrieges nach Urkunden und Augenzeugen (in German) 1, Stuttgart: Rieger'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung

- Zimmermann, Wilhelm (1856), Geschichte des großen Bauernkrieges nach Urkunden und Augenzeugen (in German) 2, Stuttgart: Rieger'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung