Balkans Campaign (World War I)

| Balkans Theatre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War I | |||||||

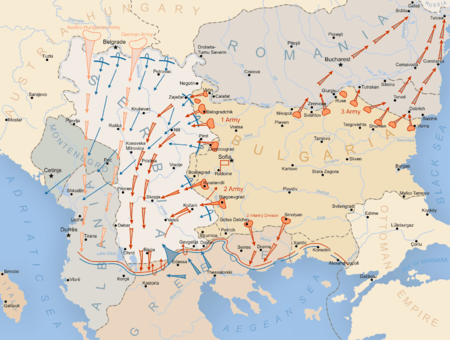

The Balkan Peninsula. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

The Balkans Campaign of World War I was fought between the Central Powers, represented by Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, Germany and the Ottoman Empire on one side and the Allies, represented by France, Montenegro, Russia, Serbia, and the United Kingdom (and later Romania and Greece, who sided with the Allied Powers) on the other side.

Overview

The prime cause of World War I being the hostility between Serbia and Austria-Hungary, so it isn't surprising that some of the earliest fighting took place between Serbia and its powerful neighbour to the north: Austria-Hungary. Serbia held out against Austria-Hungary for more than a year before it was conquered in late 1915.

Dalmatia was a strategic region during World War I that both Italy and Serbia intended to seize from Austria-Hungary. Italy entered the war in 1915 upon agreeing to the Treaty of London that guaranteed Italy a substantial portion of Dalmatia.

Allied diplomacy was able to bring Romania into the war in 1916 but this proved disastrous for the Romanians. Shortly after they joined the war, a combined German, Austrian and Bulgarian offensive conquered two-thirds of their country in a rapid campaign which ended in December 1916. However, the Romanian and Russian armies managed to stabilize the front and hold on to Moldavia.

In 1917, Greece entered the war on the Allied side, and in 1918, the multi-national Allied Army of the Orient, based in northern Greece, finally launched an offensive which drove Bulgaria to seek peace, recaptured Serbia and finally halted only at the border of Hungary in November 1918.

Serbian Campaign

The Serbian Army was successfully able to rebuff the larger Austro-Hungarian Army due to Russia's assisting invasion from the north. In 1915 the Austro-Hungarian Empire placed additional soldiers in the south front while succeeding to engage Bulgaria as an ally.

Shortly after the Serbian forces were attacked from both the north and east, forcing a retreat to Greece. Despite the loss, the retreat was successful and the Serbian Army remained operational in Greece with a newly established base.

Romanian Campaign

Romania before the war was an ally of Austria-Hungary but, like Italy, refused to join the war when it started. The Romanian government finally chose to side with the Allies in August 1916, the main reason for this was that they wanted the occupation and annexation of Transylvania, to the Kingdom of Romania. The war started as a total disaster for Romania. Before the year was out, the Germans, Hungarians, Austrians, Bulgarians and Ottomans had conquered Wallachia and Dobruja – and captured more than half of its army as POWs.

In 1917, re-trained (mainly by a French expeditionary corps under the command of General Henri Berthelot) and re-supplied, the Romanian Army, together with a disintegrating Russian Army, were successful in containing the German advance into Moldavia.

In May 1918, after the German advance in Ukraine and Russia signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Romania, surrounded by the Central Powers forces, had no other choice but to sue for peace (see Treaty of Bucharest, 1918).

After the successful offensive on the Thessaloniki front which knocked Bulgaria out of the war, Romania re-entered the war on November 10, 1918.

Italian Campaign

Prior to direct intervention in World War I, Italy occupied the port of Vlorë in Albania in December 1914.[5] Upon entering the war, Italy spread its occupation to region of southern Albania beginning in the autumn 1916.[5] Italian forces in 1916 recruited Albanian irregulars to serve alongside them.[5] Italy with permission of the Allied command, occupied Northern Epirus on 23 August 1916, forcing the neutralist Greek Army to withdraw its occupation forces from there.[5]

In June 1917, Italy proclaimed central and southern Albania as a protectorate of Italy while Northern Albania was allocated to the states of Serbia and Montenegro.[5] By 31 October 1918, French and Italian forces expelled the Austro-Hungarian Army from Albania.[5]

Dalmatia was a strategic region during World War I that both Italy and Serbia intended to seize from Austria-Hungary. Italy joined the Triple Entente Allies in 1915 upon agreeing to the London Pact that guaranteed Italy the right to annex a large portion of Dalmatia in exchange for Italy's participation on the Allied side. From 5–6 November 1918, Italian forces were reported to have reached Lissa, Lagosta, Sebenico, and other localities on the Dalmatian coast.[6]

By the end of hostilities in November 1918, the Italian military had seized control of the entire portion of Dalmatia that had been guaranteed to Italy by the London Pact and by 17 November had seized Fiume as well.[7] In 1918, Admiral Enrico Millo declared himself Italy's Governor of Dalmatia.[7] Famous Italian nationalist Gabriele d'Annunzio supported the seizure of Dalmatia, and proceeded to Zadar in an Italian warship in December 1918.[8]

Bulgarian Campaign

In the aftermath of the Balkan Wars Bulgarian opinion turned against Russia and the western powers, whom the Bulgarians felt had done nothing to help them. The government aligned Bulgaria with Germany and Austria-Hungary, even though this meant also becoming an ally of the Ottomans, Bulgaria's traditional enemy. But Bulgaria now had no claims against the Ottomans, whereas Serbia, Greece and Romania (allies of Britain and France) were all in possession of lands heavily populated by Bulgarians and thus perceived as Bulgarian.

Bulgaria, recuperating from the Balkan Wars, sat out the first year of World War I. When Germany promised to restore the boundaries of the Treaty of San Stefano, Bulgaria, which had the largest army in the Balkans, declared war on Serbia in October 1915. Britain, France and Italy then declared war on Bulgaria.

Although Bulgaria, in alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, won military victories against Serbia and Romania, occupying much of Southern Serbia (taking Nish, Serbia's war capital in November 5), advancing into Greek Macedonia, and taking Dobruja from the Romanians in September 1916, the war soon became unpopular with the majority of Bulgarian people, who suffered enormous economic hardship. The Russian Revolution of February 1917 had a significant effect in Bulgaria, spreading antiwar and anti-monarchist sentiment among the troops and in the cities.

In September 1918 the Serbs, British, French, Italians and Greeks broke through on the Macedonian front. While Bulgarian forces stopped them in Dojran and they didn't succeed to occupy Bulgarian lands, Tsar Ferdinand was forced to sue for peace.

In order to head off the revolutionaries, Ferdinand abdicated in favour of his son Boris III. The revolutionaries were suppressed and the army disbanded. Under the Treaty of Neuilly (November 1919), Bulgaria lost its Aegean coastline in favour of the Principal Allied and Associated Powers (transferred later by them to Greece) and nearly all of its Macedonian territory to the new state of Yugoslavia, and had to give Dobruja back to the Romanians (see also Dobruja, Western Outlands, Western Thrace).

Macedonian front

In 1915 the Austrians gained military support from Germany and, with diplomacy, brought in Bulgaria as an ally. Serbian forces were attacked from both north and south and were forced to retreat. The retreat was skillfully carried out and the Serbian army remained operational, even though it was now based in Greece.

The front stabilised roughly around the Greek border, through the intervention of a Franco-British-Italian force which had landed in Salonica. The German generals had not let the Bulgarian army advance towards Salonika, because they hoped they could persuade the Greeks to join the Central powers.

In 1918, after a prolonged build-up, the Allies, under the energetic French General Franchet d'Esperey leading a combined French, Serbian, Greek and British army, attacked out of Greece. His initial victories convinced the Bulgarian government to sue for peace. He then attacked north and defeated the German and Austrian forces that tried to halt his offensive.

By October 1918 his army had recaptured all of Serbia and was preparing to invade Hungary proper. The offensive halted only because the Hungarian leadership offered to surrender in November 1918.

Results

The Russians had to pour extra divisions and supplies to keep the Romanian army from being utterly destroyed again by the Austro - Hungarian and Bulgarian army.. According to John Keegan, the Russian Chief of Staff, General Alekseev, was very dismissive of the Romanian army and argued that they would drain, rather than add to the Russian reserves (John Keegan, World War I, pg 307). Alekseev was proven correct in his analysis.

The French and British kept six divisions each on the Greek frontier from 1916 till the end of 1918. Originally, the French and British went to Greece to help Serbia, but with Serbia's conquest in the fall of 1915, their continued presence was pointless. For nearly three years, these divisions accomplished essentially nothing and only tied down half of the Bulgarian army, which wasn't going to go far from Bulgaria in any event.

In fact, Keegan argues that "the installation of a violently nationalist and anti-Turkish government in Athens, led to Greek mobilization in the cause of the "Great Idea" - the recovery of the Greek empire in the east - which would complicate the Allied effort to resettle the peace of Europe for years after the war ended." (Keegan pg. 308).

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Spencer Tucker. The European powers in the First World War: an encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis, 1996, pg. 173. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ↑ http://www.cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr/page/affichepage.php?idLang=en&idPage=12546

- ↑ "British Army statistics of the Great War". Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ↑ România în războiul mondial (1916-1919), vol. I, pag. 58

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Nigel Thomas. Armies in the Balkans 1914-18. Osprey Publishing, 2001. Pp. 17.

- ↑ Giuseppe Praga, Franco Luxardo. History of Dalmatia. Giardini, 1993. Pp. 281.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Paul O'Brien. Mussolini in the First World War: the Journalist, the Soldier, the Fascist. Oxford, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Berg, 2005. Pp. 17.

- ↑ A. Rossi. The Rise of Italian Fascism: 1918-1922. New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2010. Pp. 47.

Sources

- D. J. Dutton, 'The Balkan Campaign and French War Aims in the Great War', The English Historical Review, Vol. 94, No. 370 (Jan., 1979), pp. 97–113

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Balkans theatre of World War I. |

| Bulgaria in World War I | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prelude | South-western front: Serbian Campaign, Macedonian front | Romanian front • Outcome • Others | Important persons |

|

1912–1913 1913

Neutrality

1914 1915

|

Commanders

Nikola Zhekov • Kliment Boyadzhiev • Georgi Todorov• Stefan Nerezov • Vladimir Vazov

Field Armies

Battles

1915 Morava Offensive • Ovche Pole Offensive • Kosovo Offensive (1915) • Battle of Krivolak 1916 First battle of Doiran • Battle of Lerin • Battle of Struma • Monastir Offensive 1917 Second battle of Doiran • 2nd Cerna Bend • Second battle of Monastir 1918 Battle of Skra-di-Legen • Battle of Dobro Pole • Third battle of Doiran |

Commanders

Nikola Zhekov • Panteley Kiselov • Stefan Toshev • Todor Kantardzhiev • Ivan Kolev

Field Armies

Battles

1916 Battle of Turtucaia • Battle of Dobrich • First Cobadin • Flămânda Offensive • Second Cobadin • Battle of Bucharest Outcome

1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk • Armistice of Focşani • Treaty of Bucharest • Protocol of Berlin Outcome

Others

|

|