Baalbek

| Baalbeck بعلبك | |

|---|---|

|

Temple of Jupiter in Baalbeck | |

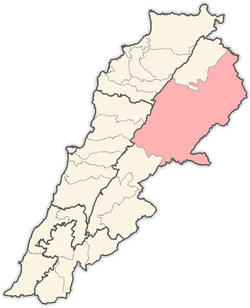

Baalbeck Location in Lebanon | |

| Coordinates: 34°0′25″N 36°12′14″E / 34.00694°N 36.20389°ECoordinates: 34°0′25″N 36°12′14″E / 34.00694°N 36.20389°E | |

| Country |

|

| Governorate | Beqaa Governorate |

| District | Baalbeck District |

| Area | |

| • City | 7 km2 (3 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 16 km2 (6 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,170 m (3,840 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City | 82,608 |

| • Metro | 105,000 |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| • Summer (DST) | +3 (UTC) |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iv |

| Designated | 1984 (8th session) |

| Reference no. | 294 |

| State Party |

|

| Region | Arab States |

Baalbeck, also known as Baalbek (Arabic: بعلبك / ALA-LC: Baʻalbik, Lebanese pronunciation: [ˈbʕalbik]) is a town in the Beqaa Valley of Lebanon situated east of the Litani River. Known as Heliopolis (Greek: Ἡλιούπολις) during the period of Roman rule, it was one of the largest sanctuaries in the empire and contains some of the best preserved Roman ruins in Lebanon. The gods that were worshipped at the temple – Jupiter, Venus, and Bacchus – were grafted onto the indigenous deities of Hadad, Atargatis, and a young male god of fertility. Local influences are seen in the planning and layout of the temples, which vary from the classic Roman design.

Baalbeck is home to the annual Baalbeck International Festival. The town is about 85 km (53 mi) northeast of Beirut and about 75 km (47 mi) north of Damascus. It has a population of approximately 82,608, mostly Shia Muslims.

Archaeology

Tell Baalbeck

There has been much conjecture about earlier levels at Baalbeck with suggestions that it may have been an ancient settlement. The German expedition in 1898 reporting nothing prior to Roman occupation.[1] Recent archaeological finds have been discovered in the deep trench at the edge of the Jupiter temple platform during cleaning operations. These finds date the site Tell Baalbeck from the PPNB neolithic to the Iron Age. They include several sherds of pottery including a teapot spout, evident to date back to the early bronze age.[2] Previous excavations under the Roman flagstones in the Great Court unearthed three skeletons and a fragment of Persian pottery dated to around 550–330 BC. The fragment featured cuneiform letters and images of figurines.[3]

History

Prehistory

The history of settlement in the area of Baalbeck dates back about 9,000 years, with almost continual settlement of the tell under the Temple of Jupiter, which was a temple since the pre-Hellenistic era.[4]

Nineteenth century Bible archaeologists wanted to connect Baalbeck to the "Baalgad" mentioned in Joshua 11:17, but the assertion has seldom been taken up in modern times. In fact, this minor Phoenician city, named for the "Lord (Baal) of the Beqaa valley" lacked enough commercial or strategic importance to be rated worthy of mention in Assyrian or Egyptian records so far uncovered, according to Hélène Sader, professor of archaeology at the American University of Beirut.

Heliopolis, the City of the Sun

After Alexander the Great conquered the Near East in 334 BC, the existing settlement was named Heliopolis (Ἡλιούπολις) from helios, Greek for sun, and polis, Greek for city. The city retained its religious function during Greco-Roman times, when the sanctuary of the Heliopolitan Jupiter-Baal was a pilgrimage site. Trajan's biographer records that the emperor consulted the oracle there. Trajan inquired of the Heliopolitan Jupiter whether he would return alive from his wars against the Parthians. In reply, the god presented him with a vine shoot cut into pieces. Macrobius, a Latin grammarian of the 5th century, mentioned Zeus Heliopolitanus and the temple, a place of oracular divination. Starting in the last quarter of the 1st century BC (reign of Augustus) and over a period of two centuries (reign of Philip the Arab), the Romans had built a temple complex in Baalbeck consisting of three temples: Jupiter, Bacchus and Venus. On a nearby hill, they built a fourth temple dedicated to Mercury.

The city, then known as Heliopolis (there was another Heliopolis in Egypt), was made a colonia by Septimius Severus in 193, having been part of the territory of Berytus on the Phoenician coast since 15 BC. Work on the religious complex there lasted over a century and a half and was never completed. The dedication of the present temple ruins, the largest religious building in the entire Roman empire, dates from the reign of Septimius Severus (193–211 AD), whose coins first show the two temples. In commemoration, no doubt, of the dedication of the new sanctuaries, Severus conferred the rights of the ius Italicum on the city.

Today, only six Corinthian columns remain standing. Eight more were disassembled and shipped to Constantinople under Justinian's orders circa 532-537 CE, for his basilica of Hagia Sophia.

The greatest of the three temples was sacred to Jupiter Baal, ("Heliopolitan Zeus"), identified here with the sun, and was constructed during the first century AD (completed circa 60 AD) on top of a podium and foundations presumably from a previous temple of undetermined origin or date.[5][6] With it were associated a temple to Venus and a lesser temple in honor of Bacchus (though it was traditionally referred to as the "Temple of the Sun" by Neoclassical visitors, who saw it as the best-preserved Roman temple in the world – it is surrounded by forty-two columns nearly 20 meters in height). Thus three Eastern deities were worshipped in Roman guise: thundering Jove, the god of storms, stood in for Baal-Hadad, Venus for ‘Ashtart and Bacchus for Anatolian Dionysus.

The original number of Jupiter columns was 54 columns. The architrave and frieze blocks weigh up to 60 tons each, and one corner block over 100 tons, all of them raised to a height of 19 m (62.34 ft) above the ground.[7] This was thought to have been done using Roman cranes. Roman cranes were not capable of lifting stones this heavy; however, by combining multiple cranes they may have been able to lift them to this height. If necessary they may have used the cranes to lever one side up a little at a time and use shims to hold it while they did the other side.

The Roman construction involved the creation of an immense raised plaza onto which the actual buildings were placed. Another of the Roman ruins, the Great Court, has six 20 m (65.62 ft) tall stone columns surviving, out of an original 128 columns. It was built 5 metres on top of an earlier gigantic, monumental T-shaped construction consisting of podium, staircase and foundation walls.[8] These walls are built of about 24 monoliths at their lowest level each weighing approximately 300 tons. The western, tallest retaining wall has a second course of monoliths containing the famous trilithon: a row of three stones, each over 19 metres long, 4.3 metres high and 3.6 metres broad, cut from limestone. They weigh approximately 800 tons each.[9]

A fourth, still larger stone called Stone of the Pregnant Woman lies unused in a nearby quarry about 1 mile from the town.[10] – its weight, often exaggerated, is estimated at 1,000 tons.[11] An even larger stone, weighing approximately 1,200 tons,[12] lies in the same quarry across the road

In the summer of 2014, a German team from the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, led by Jeanine Abdul Massih of the Lebanese University excavating the site discovered a sixth, much larger stone suggested to be the world's largest ancient block. The stone was found underneath and next to the Stone of the Pregnant Woman ("Hajjar al-Hibla") and measures around 19.6 × 6 × 5.5 metres. It is estimated to weigh an impressively heavy 1,650 tons.[13]

Jupiter-Baal was represented locally (on coinage) as a beardless god in long scaly drapery holding a whip in his right hand and thunderbolts and ears of wheat in his left. Two bulls supported him. In this guise he passed into European worship in the 3rd century and 4th century. The icon of Helipolitan Zeus (in A.B. Cook, Zeus, i:570–576) bore busts of the seven planetary powers on the front of the pillarlike term in which he was encased. A bronze statuette of this Heliopolitan Zeus was discovered at Tortosa, Spain; another was found at Byblos in Phoenicia. A comparable iconic image is the Lady of Ephesus.[14]

Other emperors enriched the sanctuary of Heliopolitan Jupiter each in turn. Nero (54–68 AD) built the tower-altar opposite the Temple of Jupiter; Trajan (98–117) added the forecourt to the Temple of Jupiter, with porticos of pink granite brought from Aswan in Egypt. Antoninus Pius (138–161) built the Temple of Bacchus, the best preserved of the sanctuary's structures, for it was protected by the rubble of the site's ruins. It is enriched with refined reliefs and sculpture. Septimius Severus (193–211) added a pentagonal temple of Venus, who as Aphrodite had enjoyed an early Syrian role with her consort Adonis ("Lord", the Aramaic translation of "Baal."). Emperor Philip the Arab (244–249) was the last to add a monument at Heliopolis: the hexagonal forecourt. When he was finished Heliopolis and Praeneste in Italy were the two largest sanctuaries in the Western world.

The extreme license of the Heliopolitan worship of Aphrodite was often commented upon by early Christian writers, who competed with one another to execrate her worship. Eusebius of Caesarea, down the coast, averred that 'men and women vie with one another to honour their shameless goddess; husbands and fathers let their wives and daughters publicly prostitute themselves to please Astarte'. Constantine, making an effort to curb the Venus cult, built a basilica in Heliopolis. Theodosius I erected another, with a western apse, occupying the main court of the Jupiter temple, as was Christian practice everywhere. The vast stone blocks of its walls were taken from the temple. Today nothing of the Theodosian basilica remains.

Early Islamic period

In 637 AD, the Muslim army under Abu Ubaida ibn al-Jarrah captured Baalbeck after defeating the Byzantine army at Battle of Yarmouk. It was still an opulent city and yielded rich plunder. It became a bone of contention between the various Syrian dynasties and the caliphs first of Damascus, then of Egypt. The place was fortified and took on the name al-Qala‘ ("fortress"; see Alcala) but in 748 was sacked again with great slaughter. The Byzantine Emperor John Tzimisces sacked the city in 975. In 1090 it passed to the Seljuks and in 1134 to Zengi; but after 1145 it remained attached to Damascus and was captured by Saladin in 1175. The Crusaders raided its valley more than once but never took the city. Three times shaken by earthquakes in the 12th century, it was dismantled by 1260 when it served as the Mongol base for the last unsuccessful attack upon the Mamlukes of Egypt. But it revived, and most of its fine mosque and fortress architecture, still extant, belonged to the reign of Sultan Qalawun (1282), during which Abulfeda describes it as a very strong place. In 1400 Timur pillaged it.

Ottoman period

In 1517, it passed, with the rest of Syria, to the Ottoman Empire. But Ottoman jurisdiction was merely nominal in the Lebanon, since the Ottomans awarded the Harfush’s family of Baalbek the local iltizam concessions plus a nominal military rank (the district governorship of Homs) in recognition of their social prominence among the Shiite village population of the Bekaa Valley.[15] Baalbeck, badly shaken in the Near East earthquake of 1759, was really in the hands of the Metawali who retained it against other Lebanese tribes. The colossal and picturesque ruins attracted particularly intrepid Westerners since the 18th century. English visitor Robert Wood was not simply a tourist: his carefully measured drawings were engraved for The Ruins of Baalbeck (1757), which provided some excellent new detail in the Corinthian order that British and European Neoclassical architects added to their vocabulary. Robert Adam, for example, based a bed[16] and one of the ceilings at Osterley House on the ceiling of the Temple of Bacchus, and the portico of St George's, Bloomsbury is based on that temple's portico.[17]

Even after Jezzar Pasha, the rebel governor of Acre province, broke the power of the Metawali in the last half of the 18th century, Baalbeck was no destination for the traveller unaccompanied by an armed guard. The chaos that succeeded his death in 1804 was ended only by the Egyptian occupation in 1832. With the treaty of London (1840) Baalbek became really Ottoman, the Encyclopædia Britannica (1911) reported and since about 1864 had attracted great numbers of tourists. In November 1898, the German Emperor Wilhelm II on his way to Jerusalem and passing by Baalbeck was equally struck by the magnificence of the ruins projecting from the rubble and the dreary condition. Within a month, the German archaeological team he dispatched was at work on the site. The campaign produced meticulously presented and illustrated series of volumes.

2006 Israel-Lebanon conflict

On August 4, 2006, as part of the 2006 Lebanon War, Israeli helicopter-borne soldiers supported by bombs from aircraft entered the Shi'ite Islamic Hikmeh Hospital in Baalbeck to capture senior members of Hezbollah who were considered to be responsible for the kidnapping of the two Israeli IDF soldiers on July 13, 2006, and who were believed to be residing in the building. The fighting caused minor damage to the hospital. Several gunmen were killed, and weapons and ammunition were seized from inside the hospital building. No patients were hospitalized at the time.[18][19] It has been reported that during the conflict, vibrations caused by bombs damaged the ruins. UNESCO offered help to coordinate restoration efforts.[20]

World Heritage Site

"Baalbeck, with its colossal structures, is one of the finest examples of Imperial Roman architecture at its apogee", UNESCO reported in making Baalbeck a World Heritage Site in 1984.[21] When the committee inscribed the site, it expressed the wish that the protected area include the entire town within the Arab walls, as well as the southwestern extramural quarter between Bastan-al-Khan, the Roman site and the Mameluk mosque of Ras-al-Ain. Lebanon's representative gave assurances that the committee's wish would be honored.

Moving the stones

The quarry was slightly higher up[22][23] than the temple itself so no lifting was required to move the stones the 800 meters (2,600 ft) to the temple. In 1977, Jean-Pierre Adam made a brief study suggesting the large blocks could have been moved on rollers with machines using capstans and pulley blocks, a process which he theorised could use 512 workers to move a 557 tonne block (approximately 243 tonnes lighter than the trilithon blocks).[22][24] Archaeologists date the temple to the Julio-Claudian period, the first two centuries AD.[25] The temple was built over an earlier unfinished structure. According to Daniel Lohmann, "The unfinished pre-Roman sanctuary construction was incorporated into a master plan of monumentalisation. Apparently challenged by the already huge pre-Roman construction, the early imperial Jupiter sanctuary shows both an architectural megalomaniac design and construction technique in the first half of the first century AD."[26]

Gallery

-

The Eastern Façade

-

Temple of Jupiter

-

Temple of Jupiter From Below

-

Temple of Jupiter from the Great Court

-

Great court

-

Temple of Bacchus

-

Entrance into the Bacchus Temple

-

Propylaea at the entrance of the site

-

Pillars of the former mosque

-

Plan of the temple complex

-

View of Baalbeck 1890–1900

-

Exterior of Baalbeck temple. Shaft of unknown function leads to the interior of what is now the museum.

-

Roof sculpture of an unknown God

-

.jpg)

Roof sculpture of Ceres

-

.jpg)

Roof sculpture supposedly of Mark Antony

-

.jpg)

Roof sculpture supposedly of Cleopatra

Climate

Baalbeck experiences a semi-arid Mediterranean climate with hot, dry summers and relatively cold, sometimes snowy, winters.

| Climate data for Baalbeck | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) |

9.3 (48.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

24.1 (75.4) |

29.2 (84.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.5 (90.5) |

28.6 (83.5) |

20.2 (68.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

20.26 (68.47) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

4.9 (40.8) |

8.0 (46.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.6 (76.3) |

20.8 (69.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

10.6 (51.1) |

5.8 (42.4) |

14.23 (57.63) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.5 (31.1) |

0.2 (32.4) |

2.6 (36.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

10.0 (50) |

14.2 (57.6) |

16.1 (61) |

16.5 (61.7) |

12.7 (54.9) |

9.5 (49.1) |

5.2 (41.4) |

1.7 (35.1) |

7.88 (46.21) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 149 (5.87) |

112 (4.41) |

96 (3.78) |

25 (0.98) |

10 (0.39) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

21 (0.83) |

69 (2.72) |

111 (4.37) |

593 (23.35) |

| Avg. rainy days | 14 | 12 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 11 | 69 |

| Source: chinci | |||||||||||||

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Baalbeck is twinned with:

See also

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- List of colossal sculpture in situ

- List of megalithic sites

Notable people

- Saint Barbara

- Assi El Helani, Lebanese singer

References

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Baalbek". Encyclopædia Britannica 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 89–90.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Baalbek". Encyclopædia Britannica 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 89–90.- Adam, Jean-Pierre (1977), "À propos du trilithon de Baalbeck: Le transport et la mise en oeuvre des mégalithes", Syria 54 (1/2): 31–63, doi:10.3406/syria.1977.6623

- Frauberger, Heinrich: Die Akropolis von Baalbeck (Keller : Frankfurt a. M., 1892. – 14, 22 S. : überw. Ill.) (pdf 24,6 MB)

- Ruprechtsberger, Erwin M. (1999), "Vom Steinbruch zum Jupitertempel von Heliopolis/Baalbeck (Libanon)", Linzer Archäologische Forschungen 30: 7–56

Notes

- ↑ Theodor Wiegand (1925). Baalbeck: Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen und Untersuchungen in den Jahren 1898 bis 1905. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-002370-1. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae; Frances Pinnock; Licia Romano; Lorenzo Nigro (2010). Proceedings of the 6th International Congress of the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East: 5–10 May 2009, "Sapienza", Universita di Roma. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 208–. ISBN 978-3-447-06216-9. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ↑ Nina Jidejian (1975). Baalbeck: Heliopolis, city of the sun, p. 15. Dar el-Machreq Publishers : distribution, Librairie Orientale. ISBN 978-2-7214-5884-1. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ↑ German Archaeological Institute The urban planning and historical development of the Roman sanctuary of Baalbeck

- ↑ Rowland Jr, Benjamin "The Vine-Scroll in Gandhāra", Artibus Asaie Vol. 19, No. 3/4 (1956), pp. 353–361 "It is apparent from a graffito on one of the columns of the Temple of Jupiter that that building was nearing completion in 60 A.D."

- ↑ Lohmann, Daniel. "Giant Strides towards Monumentality: The architecture of the Jupiter Sanctuary in Baalbek/Heliopolis", Bolletino di Archaologia, Volume Speciale, 2010, pp. 29–30 "Due to the lack of remains of temple architecture, it can be assumed that the temple this terrace was built for was never completed or entirely destroyed before any new construction started."

- ↑ J. J. Coulton: "Lifting in Early Greek Architecture", The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 94 (1974), p. 16

- ↑ Lohmann (2010) p. 29 "Current survey and interpretation, show that a pre-Roman floor level about 5 m lower than the late Great Roman Courtyard floor existed underneath"

- ↑ Adam 1977, p. 52

- ↑ Alouf, Michael M., 1944: History of Baalbeck. American Press. p. 139

- ↑ Ruprechtsberger 1999, p. 15

- ↑ Ruprechtsberger 1999, p. 17

- ↑ Kehrer, Nicole., Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Libanesisch-deutsches Forscherteam entdeckt weltweit größten antiken Steinblock in Baalbek, 21.11.14

- ↑ Robert Graves, The Greek Myths I.4

- ↑ THE SHIITE EMIRATES OF OTIOMAN SYRIA (MID-17m -MID-18m CENTURY), STEFAN HELMUT WINTER, THE UNlVERSIlY OF CHICAGO, CHICAGO, ILUNOIS AUGUST 2002, Page 238.

- ↑ "Center for American Architecture and Design – Center 9". Utexas.edu. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "St George's Bloomsbury. (Church of England)". Web.archive.org. 2007-11-04. Archived from the original on 2007-11-04. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ↑ "Minute by Minute:: August 2". lebanonupdates.blogspot. 2 August 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Butters, Andrew Lee (August 2, 2006). "Behind the Battle for Baalbeck: Residents in the ancient Lebanese city knew an Israeli attack was imminent". Time.com. Retrieved 14 September 2006.

- ↑ Karam,Zeina, "Cleanup to Start at old sites in Lebanon", AP, 4 October 2006

- ↑ "The Entrance to the Temple of Jupiter". World Digital Library. 1890–1923. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Adam, Jean Pierre; Anthony Mathews (1999). Roman Building: Materials and Techniques. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-415-20866-6.

- ↑ Hastings, James (2004, originally published 1898–1904). A Dictionary of the Bible: Volume IV: (Part II: Shimrath -- Zuzim), Volume 4. University Press of the Pacific. p. 892. ISBN 978-1-4102-1729-5. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Adam, Jean-Pierre., A propos du trilithon de Baalbeck. Le transport et la mise en oeuvre des mégalithes, Syria, 1977, Volume 54, Numéro 54-1-2, pp. 31–63.

- ↑ Kropp, Andreas; Daniel Lohmann (April 2011). "‘Master, look at the size of those stones! Look at the size of those buildings!’1 Analogies in Construction Techniques Between the Temples at Heliopolis (Baalbeck) and Jerusalem". Levant (1): 38–50. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ↑ Lohmann (2010), p. 29. "

- ↑ "Climate History for Baableck, Lebanon". Retrieved October 2011.

- ↑ Syaifullah, M. (October 26, 2008). "Yogyakarta dan Libanon Bentuk Kota Kembar". Tempo Interaktif. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

Further reading

- "Ba'albek", Cook's Tourists' Handbook for Palestine and Syria, London: T. Cook & Son, 1876

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Baalbeck. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baalbek. |

- 360 Panorama of the Temples of Baalbeck

- The monuments of Baalbeck in panorama photography

- Google Maps satellite view

- UNESCO World Heritage Review describing Baalbeck

- Baalbeck International Festival – music, from traditional Arabic to rock

- Archaeological research in Baalbeck

| ||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||