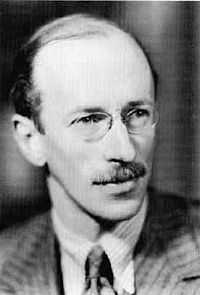

B. H. Liddell Hart

Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart (31 October 1895 – 29 January 1970), commonly known throughout most of his career as Captain B. H. Liddell Hart, was an English soldier, military historian and military theorist. He is often credited with greatly influencing the development of armoured warfare,[1] although some research casts some doubt on the extent of his influence upon the pre-war German military.[2]

Life and career

Childhood

Born in Paris, the son of an English Methodist minister, Liddell Hart received his formal academic education at St Paul's School in London and at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. His mother's side of the family, the Liddells, came from Liddesdale, on the border with Scotland, and were associated with the South-Western Railway. The Harts were farmers from Gloucestershire and Herefordshire.[3] As a child he was fascinated by aviation.[4]

World War I

On the outbreak of World War I in 1914 Liddell Hart volunteered to become an officer in the Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. He fought on the Western Front. Liddell Hart's front line experience was relatively brief, confined to two short spells in the autumn and winter of 1915, being sent home from the front after suffering concussive injuries from a shell burst. He was promoted to the rank of captain. He returned to the front for a third time in 1916, in time to participate in the Battle of the Somme. He was hit three times without serious injury before being badly gassed and sent out of the line on 19 July 1916.[5] His battalion was nearly wiped out on the first day of the offensive, a part of the 60,000 casualties suffered in the heaviest single day's loss in British history. The experiences he suffered on the Western Front profoundly affected him for the rest of his life.[6] Transferred to be Adjutant to Volunteer units in Stroud and Cambridge, he spent a great deal of time training new units.[7] During this time he wrote several booklets on infantry drill and training, which came to the attention of General Sir Ivor Maxse. After the war he transferred to the Army Educational Corps and was given the opportunity to prepare a new edition of the Infantry Training Manual. In this manual Liddell Hart strove to instill the lessons of 1918, and carried on a correspondence with Maxse, a commanding officer during the Battle of Hamel and the Battle of Amiens.[8] These battles provided a practical demonstration of tactics for attacking an entrenched enemy.

Marriage

In April 1918 Liddell Hart married Jessie Stone, the daughter of J. J. Stone – who had been his assistant adjutant at Stroud[9] – and their son Adrian was born in 1922.[10]

Journalist and military historian

Liddell Hart was placed on half-pay from 1924.[11] He later retired from the Army in 1927. Two mild heart attacks in 1921 and 1922, probably the long-term effects of his gassing, precluded his further advancement in the downsized post-war army. He spent the rest of his career as a theorist and writer. In 1924 he became a lawn tennis correspondent and assistant military correspondent for the Morning Post covering Wimbledon and in 1926 publishing a collection of his tennis writings as The Lawn Tennis Masters Unveiled.[12] He worked as the Military Correspondent of the Daily Telegraph from 1925 to 1935, and of The Times from 1935 to 1939.

In the mid to late twenties Liddell Hart wrote a series of histories of major military figures, through which he advanced his ideas that the frontal assault was a strategy that was bound to fail at great cost in lives. He argued that the tremendous losses Britain suffered in the Great War were due to her commanding officers not appreciating this fact of history. He believed the British decision in 1914 to directly intervene on the Continent with a great army was a mistake. He claimed that historically "the British way in warfare" was to leave Continental land battles to her allies, intervening only through naval power, with the army fighting the enemy away from its principal front in a "limited liability".[13] In the histories he wrote on Scipio Africanus Major (1926), the Great Captains (1927) and Sherman (1929) he made the argument for maneuver warfare and taking the indirect approach to reach one's objectives. In the thirties Liddell Hart continued along this vein, and added the admonition that in the Great War Britain had moved away from her traditional strategy of using her naval superiority to attack her adversaries in places unexpected and at times of her choosing, and instead committed herself to a large army of conscripted men who fought on the Continent in direct confrontation with continental armies. The idea of keeping the British army off the continent thereby keeping British casualties low appealed to many people, including Neville Chamberlain.

In a series of articles for The Times from November 1935 to November 1936, Liddell Hart argued that Britain's role in the next European war could be entrusted to the air force. This was one avenue Liddell Hart theorized Britain could pursue to defeat her enemies while avoiding the high casualties and limited influence that Britain could impart by placing a large conscript army on the Continent. He believed that Britain should inform the French that Britain would provide assistance from the sea and air.[14] These ideas influenced Chamberlain, then Chancellor, who argued in discussions of the Defence Policy and Requirements Committee for a strong air force rather than a large army that would fight on continental Europe.[15] The idea of winning a war through air power alone was not new. Guilio Douhet had put forward a similar argument in "Command of the Air" published in 1921.[16] Liddell Hart was again taking a developing technology and making expanded use of it to project power.

Influence on Chamberlain

As Prime Minister in 1937, Chamberlain placed Liddell Hart in a position of influence behind British grand strategy of the late thirties.[17] In May he prepared schemes for the reorganization of the British Army for defence of the empire and delivered them to Sir Thomas Inskip, the Minister for the Co-Ordination of Defence. In June he gained an introduction to the Secretary of State for War, Leslie Hore-Belisha. Through July 1938 the two had an unofficial, close advisorial relationship. Liddell Hart provided Hore-Belisha with ideas that he would argue for in Cabinet or committees.[17] On 20 October 1937, Chamberlain wrote to Hore-Belisha: "I have been reading in Europe in Arms by Liddell Hart. If you have not already done so you might find it interesting to glance at this, especially the chapter on the “Role of the British Army”". Hore-Belisha wrote in reply: "I immediately read the “Role of the British Army” in Liddell Hart's book. I am impressed by his general theories".[18]

Liddell Hart, with Hore-Belisha, drafted a paper on 'The Role of the Army' in November 1937 in which they argued that home defence and empire defence were the primary responsibilities of the army, and that the defence of other people's territory was a secondary role.[19] On 15 November Hore-Belisha wrote to Liddell Hart that "the Cabinet was moving towards the discontinuance of an Expeditionary Force for the Continent"[20] and the next day wrote again to Liddell Hart, claiming Chamberlain was pleased by their paper on the role of the British Army and had requested from Liddell Hart a paper on 'The Reorientation of the Regular Army for Imperial Defence".[21]

World War II

With the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 the War Cabinet reversed the Chamberlain policy advanced by Liddell Hart. With Europe on the brink of war and Germany threatening an invasion of Poland, the cabinet chose instead to advocate a British and Imperial army of 55 divisions, for intervention on the Continent to come to the aid of Poland, Norway and France.[22]

Post-World-War-II

Shortly after World War II Liddell Hart acting in an official capacity had opportunity to interview many of the German generals in captivity and gain their perspective on the events of the war. Liddell Hart provided commentary on their outlook. The work was published as The Other Side of the Hill (UK Edition, 1948) and The German Generals Talk (condensed US Edition, 1948). General Guderian was not among those officers interviewed by Liddell Hart. A few years later Liddell Hart was given the opportunity to review the notes that Erwin Rommel had kept during the war. Rommel had kept these notes with the intention of writing of his experiences after the war. Some of the notes had been destroyed by Rommel and the rest had been looted by Americans, but were later found and returned to Frau Rommel. The Rommel family allowed Liddell Hart to review these notes, along with his letters home to his wife and son. The writings, along with notes and commentary by General Fritz Bayerlein and Liddell Hart were published in 1953 as The Rommel Papers. Many years later historian Jay Luvaas had the opportunity to speak with General Friedrich von Mellenthin, a former Rommel staff officer. According to Luvaas: Since Liddell Hart rarely if ever deviated from his established schedule, it was my responsibility to entertain the general for several hours, which provided the opportunity to inquire whether Rommel had in fact ever mentioned Liddell Hart in his presence. "Oh yes," he assured me, "many times. He had a good opinion of his writings. That is why I have come from South Africa to meet him."[23]

The Queen made Liddell Hart a Knight Bachelor in the New Year Honours of 1966.

Theories

Theory of the Indirect Approach

Liddell Hart set out following World War I to address the causes of the war's high casualty rate. He arrived at a set of principles that he considered the basis of all good strategy. Liddell Hart believed the failure to act upon these principles which was the case for nearly all commanders in World War I led to the high casualty rate.

He reduced this set of principles to a single phrase: the indirect approach. The indirect approach had two fundamental principles:

- direct attacks against an enemy firmly in position almost never work and should never be attempted

- to defeat the enemy one must first upset his equilibrium, which is not accomplished by the main attack, but must be done before the main attack can succeed.

In Liddell Hart's words,

In strategy the longest way round is often the shortest way there; a direct approach to the object exhausts the attacker and hardens the resistance by compression, whereas an indirect approach loosens the defender's hold by upsetting his balance.

As a corollary he explained

The profoundest truth of war is that the issue of battle is usually decided in the minds of the opposing commanders, not in the bodies of their men.

Liddell Hart argued that success can be gained by keeping one's enemy uncertain about the situation and one's intentions. By delivering what he does not expect and has therefore not prepared for, he will be mentally defeated.

Liddell Hart explained that one should not employ a rigid strategy revolving around powerful direct attacks nor fixed defensive positions. Instead, he preferred a more fluid elastic defence, where a mobile contingent can move as necessary in order to satisfy the conditions for the indirect approach. He later offered Erwin Rommel's Northern Africa campaign as a classic example of this theory. Liddell Hart's theory closely matches what is currently referred to as Manoeuvre warfare, and has been advanced by John Boyd and his OODA loop Theory of combat and maneuver.

He arrived at his conclusions following his own experience of heavy losses suffered by Britain in the static warfare of the First World War. In developing his theory about indirect approach he looked back through history for those commanders whose careers supported his theories: men such as Sun Tzu, Napoleon, and Belisarius. Perhaps the best example was the career of William Tecumseh Sherman. In discussing these commanders Liddell Hart sought to illustrate and promote his idea of the indirect approach. He also advocated the indirect approach as a valid strategy in other fields of endeavour, such as business.

As of 2009, Liddell Hart's personal papers and library form the central collection in the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives at King's College London.[24]

Controversy over influence on the Panzerwaffe

Following the Second World War Liddell Hart pointed out that the German Wehrmacht adopted theories developed from those of J.F.C. Fuller and from his own, and that it used them against the United Kingdom and its allies (1939-1945) with the practice of what became known as Blitzkrieg warfare.[25] Some revisionist military historians have questioned the extent of the influence which the British officers, and in particular Liddell Hart, had in the development of the method of war practiced by the Panzerwaffe in 1939-1941.

That Fuller and Liddell Hart played a role is supported by multiple sources, including Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma, one of the early developers of armoured warfare in Germany, who said: "The German tank officers closely followed the British ideas on armoured warfare, particularlarly those of Liddell Hart, also General Fuller's."[26] Two influential German officers with ties to the Nazi regime, Werner von Blomberg and Walther von Reichenau, read much of Liddell Hart's work and translated Liddell Hart's "The British Way in Warfare" into German. They circulated his ideas on mechanization throughout the Reichswehr.[27] Guderian reviewed and expanded upon these ideas. In discussing the developments in armoured warfare in the European nations and Soviet Russia in his book Achtung – Panzer!, Guderian underscored the conflicts between the British military command and the British protagonists for mechanization, specifically naming General Fuller, Martel and Liddell-Hart.[28] This is further illustrated by Major General F. W. von Mellenthin, who in contrasting the development of German armoured warfare techniques with British developments at the same time, commented "In spite of warnings by Liddell Hart on the need for co-operation between tanks and guns, British theories of armoured warfare tended to swing in favor of the 'all-tank' concept."[29] At one point the Chief of the German General Staff, Ludwig Beck, a more conservative officer, reportedly became so exasperated with Guderian and other younger officers expounding on the potential of armoured warfare that he said he wished he could have six months without having to hear Liddell Hart's name.[30] In "Achtung – Panzer!", written in 1937, Guderian mentioned Liddell Hart as a proponent of mechanization:

In order to overcome the first of these disadvantages, the one related to unsupported armour, the protagonists of mechanization - General Fuller, Martel, Liddell Hart and others - advocated reinforcing the all tank units by infantry and artillery mounted on permanently assigned armoured vehicles, together with mechanized engineers, and signals, support and supply elements.[31]

Notes Guderian brought to his first meeting with Hitler as the Inspector General of Armoured Troops (1943) indicate he intended to read out a paper by Liddell Hart on "the organization of armoured forces, past and future".[32]

Despite ample access and evidence to the facts, Shimon Naveh sought to undermine Liddell Hart's influence in Israeli military circles by claiming that after World War II Liddell Hart "created" the idea of Blitzkrieg as a military doctrine:

"It was the opposite of a doctrine. Blitzkrieg consisted of an avalanche of actions that were sorted out less by design and more by success."[33]

Naveh advanced this argument as a means to attack the credibility of Liddell Hart, who had become highly influential among the Israeli military.[34]

Naveh claimed that by "manipulation and contrivance, Liddell Hart distorted the actual circumstances of the Blitzkrieg formation and obscured its origins. Through his indoctrinated idealization of an ostentatious concept he reinforced the myth of Blitzkrieg. By imposing, retrospectively, his own perceptions of mobile warfare upon the shallow concept of Blitzkrieg, he created a theoretical imbroglio that has taken 40 years to unravel".[35] Naveh claimed that in his letters to German generals Erich von Manstein and Guderian, as well as to relatives and associates of Rommel, Liddell Hart "imposed his own fabricated version of Blitzkrieg on the latter and compelled him to proclaim it as original formula".[36]

(Naveh has a long history of attacking the intelligence and character of people he is in intellectual conflict with, including the General Staff of the Israel Defense Forces. Of these men he claimed in an interview: "They are on the brink of illiteracy. The army's tragedy is that it is managed by battalion commanders who were good and generals who did not receive the tools to cope with their challenges. Halutz is not stupid, even Dudu Ben Bashat is not stupid, even though he is an idiot, and his successor, Major General Uri Marom (sic), is a total bastard."[37])

To buttress his attack upon Liddell Hart, Naveh sought to highlight the fact that the edition of Guderian's memoirs published in Germany differed from the one published in the United Kingdom. Guderian neglected to mention the influence of the English theorists such as Fuller and Liddell Hart in the German-language versions. One example of the influence of these men on Guderian was the report on the Battle of Cambrai published by Fuller in 1920, who at the time served as a staff officer at the Royal Tank Corps. Liddell Hart alleged that Guderian read and later took up his findings and theories on armoured warfare, which thus helped to formulate the basis of operations that would become known as Blitzkrieg warfare. These tactics involved deep penetration of the armoured formations supported behind enemy lines by bomb-carrying aircraft. Dive bombers were the principal agents of delivery of high explosives in support of the forward units.[38]

Though the German version of the Guderian memoirs mentions Liddell Hart, it did not ascribe to him his role in developing the theories behind armoured warfare. An explanation for the difference between the two translations can be found in the correspondence between the two men. In one letter to Guderian, Liddell Hart reminded the German general that he should provide him the credit he was due, offering "You might care to insert a remark that I emphasized the use of armoured forces for long-range operations against the opposing Army's communications, and also the proposed type of armoured division combining Panzer and Panzer-infantry units – and that these points particularly impressed you."[39] (In his early writings on mechanized warfare Liddell Hart had proposed that infantry be carried along with the fast-moving armoured formations. He described them as "tank marines" like the soldiers the Royal Navy carried with their ships. He proposed they be carried along in their own tracked vehicles and dismount to help take better-defended positions that otherwise would hold up the armoured units. This contrasted with Fuller's ideas of a tank army, which put heavy emphasis on massed armoured formations. Liddell Hart foresaw the need for a combined arms force with mobile infantry and artillery, which was similar but not identical to the make-up of the panzer divisions that Guderian developed in Germany.[40])

Guderian corrected the oversight, and did as Liddell Hart requested.[41] When Liddell Hart was questioned in 1968 about the oversight and difference between the English and German editions of Guderian's memoirs, he graciously replied merely: "There is nothing about the matter in my file of correspondence with Guderian himself except...that I thanked him...for what he said in that additional paragraph."[42]

MI5 controversy

On 4 September 2006, MI5 files were released which showed that in early 1944 MI5 had suspicions that plans for the D-Day invasion had been leaked. Liddell Hart had prepared a treatise titled Some Reflections on the Problems of Invading the Continent which he circulated amongst political and military figures. It is possible that in his treatise Liddell Hart had correctly deduced a number of aspects of the upcoming Allied invasion, including the location of the landings. MI5 suspected that Liddell Hart had received plans of the invasion from General Sir Alfred "Tim" Pile who was in command of Britain's anti-aircraft defences. MI5 placed him under surveillance, intercepting his telephone calls and letters. The investigation showed no suggestion that Liddell Hart was involved in any subversive activity. No case was ever brought against Pile. Liddell Hart stated his work was merely speculative. It would appear that Liddell Hart had simply perceived the same problems and arrived at similar conclusions as the Allied general staff.[1][43]

Biographies

- The principal posthumous biography of Liddell Hart, Alex Danchev's Alchemist of War: The Life of Basil Liddell Hart, written with the cooperation of Liddell Hart's widow. It reveals, for example, that Liddell Hart connived at the planting of an endorsement of his own work in the English-language version of Panzer Leader, the autobiography of Heinz Guderian.

- Brian Bond wrote Liddell Hart: a study of his military thought (Cassell, 1977; Rutgers University Press, 1977), which showed that Liddell Hart's writings in the 1920s and 1930s had a marked influence on the German officer corps, in particular German generals Werner von Blomberg and Walther von Reichenau, among many others. Bond also outlined Liddell Hart's writings on the Israel Defense Forces' campaigns of 1956 and 1967, and his broad influence among Israeli military thinkers. For balance, it should be noted that Brian Bond had a friendship and close personal links with Basil Liddell Hart, and so his work should be read with that information in mind.

- John J. Mearsheimer's "Liddell Hart and the Weight of History" (New York, 1988), published by the Cornell University Press and part of the Cornell Studies in Security Affairs, is a well-researched look at Liddell Hart's claims of theoretical prophecy and influence over the personalities and event of the Second World War. In particular, Mearsheimer uses primary evidence to look at Liddell Hart's claims to have predicted the fall of France by Blitzkrieg tactics and that he was influential with German generals and thinkers (notably Guderian) in the 1930s. What emerges are serious questions as to Liddell Hart's version of history.

In popular culture

- In his collection, Ficciones, Jorge Luis Borges intertextually weaves "Captain Liddell Hart" into the fictional short story The Garden of Forking Paths.

Bibliography of B. H. Liddell Hart

- Scipio Africanus: Greater Than Napoleon (originally: A Greater than Napoleon: Scipio Africanus; W Blackwood and Sons, London, 1926; Biblio and Tannen, New York, 1976)

- Lawn Tennis Masters Unveiled (Arrowsmith, London, 1926)

- Great Captains Unveiled (W. Blackwood and Sons, London, 1927; Greenhill, London, 1989)

- Reputations 10 Years After (Little, Brown, Boston, 1928)

- Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American (Dodd, Mead and Co, New York, 1929; Frederick A. Praeger, New York, 1960)

- The decisive wars of history (1929) (This is the first part of the later: Strategy: the indirect approach)

- The Real War (1914–1918) (1930), later republished as A History of the World War (1914–1918).

- Foch, the man of Orleans In two Volumes (1931), Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, England.

- The Ghost of Napoleon (Yale University, New Haven, 1934)

- T.E. Lawrence in Arabia and After (Jonathan Cape, London, 1934)

- World War I in Outline (1936)

- The Defence of Britain (Faber and Faber, London, 1939; Greenwood, Westport, 1980)

- The Current of War, London: Hutchinson, 1941

- The strategy of indirect approach (1941, reprinted in 1942 under the title: The way to win wars)

- The way to win wars (1942)

- The Revolution in Warfare, London: Faber and Faber, 1946

- The Other Side of the Hill. Germany's Generals. Their Rise and Fall, with their own Account of Military Events 1939–1945, London: Cassel, 1948; enlarged and revised edition, Delhi: Army Publishers, 1965

- "Foreword" to Heinz Guderian's Panzer Leader (New York: Da Capo., 1952)

- Strategy: the indirect approach, third revised edition and further enlarged London: Faber and Faber, 1954

- The Rommel Papers, (editor), 1953

- The Tanks – A History of the Royal Tank Regiment and its Predecessors: Volumes I and II (Praeger, New York, 1959)

- "Foreword" to Samuel B. Griffith's Sun Tzu: the Art of War (Oxford University Press, London, 1963)

- The Memoirs of Captain Liddell Hart: Volumes I and II (Cassell, London, 1965)

- History of the Second World War (London, Weidenfeld Nicolson, 1970)

- Why don't we learn from history? (Hawthorn Books, New York, 1971)

References

- Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Files reveal leaked D-Day plans". BBC News. 4 September 2006.

- ↑ Mearsheimer, John (1988). Liddell Hart and the Weight of History. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-2089-X.

- ↑ Bond p. 12

- ↑ Bond p. 13

- ↑ Bond pp. 16-17

- ↑ Bond p. 16

- ↑ Bond p. 19

- ↑ Bond p. 25

- ↑ Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart, The memoirs of Captain Liddell Hart: Volume 1 (1965 edition), p. 31 : "In April I married the younger daughter, Jessie, of my former assistant adjutant at Stroud, J. J. Stone..."

- ↑ Liddell Hart, Adrian John (1922–1991) at aim25.ac.uk, accessed 3 May 2011

- ↑ Bond p. 32

- ↑ "Hart, Sir Basil Henry Liddell". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- ↑ Barnett, p. 503.

- ↑ Liddell Hart, Memoirs, Vol I, pp. 296-299, pp. 380-381.

- ↑ Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (London: Methuen, 1972), pp. 497-499.

- ↑ Douhet, Giulio (1921). Command of the Air.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Barnett, p. 502.

- ↑ Minney p. 54

- ↑ Liddell Hart, Memoirs, Vol II, p. 50.

- ↑ Liddell Hart, Memoirs, Vol II, p. 55.

- ↑ Liddell Hart, Memoirs, Vol II, pp. 56-57.

- ↑ Barnett, p. 576.

- ↑ Luvaas p. 15

- ↑ Lidell Hart archive, KCL

- ↑ Naveh p. 107.

- ↑ Liddell Hart The Other Side of the Hill p. 91

- ↑ Bond p. 218

- ↑ Guderian, 1937, p. 141

- ↑ Mellenthin, p. xvi

- ↑ Bond p. 224

- ↑ Guderian, 1937, p. 141

- ↑ Guderian, 1953, p. 295

- ↑ Naveh 1997, pp. 107–108.

- ↑ Bond p. 238

- ↑ Naveh 1997, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Naveh 1997, p. 109.

- ↑ Feldman, Yotam (Oct 25, 2007). "Dr. Naveh, or, how I learned to stop worrying and walk through walls". Haaretz.

- ↑ Corum p. 42

- ↑ Danchev 1998, pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Bond p. 29

- ↑ Danchev 1998,p. 235.

- ↑ Danchev 1998, p. 239

- ↑ Michael Evans (4 September 2006). "Army writer nearly revealed plans of D-Day". London: The Times.

- Bibliography

- Bond, Brian, Liddell Hart: A Study of his Military Thought. London: Cassell, 1977.

- Cambridge Encyclopedia v.68

- Corum, James S. The Roots of Blitzkrieg: Hans von Seeckt and German Military Reform Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1992. ISBN 0-7006-0541-X.

- Danchev, Alex, Alchemist of War: The Life of Basil Liddell Hart. London: Nicholson, 1998. ISBN 0-7538-0873-0

- Danchev, Alex, "Liddell Hart and the Indirect Approach", 873-0 Journal of Military History, Vol. 63, No. 2. (1999), pp. 313–337.

- Guderian, Heinz Panzer Leader New York Da Capo Press Reissue edition, 1952.

- Luvaas, Jay Liddell Hart and the Mearsheimer Critique: A "Pupil's" Retrospective U.S. Army War College, March 1990

- Mearsheimer, John, Liddell Hart and the Weight of History. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-8014-2089-X

- von Mellenthin, Friedrich (1955). Panzer Battles: A Study of the Employment of Armor in the Second World War. Cassell. ISBN 978-0-345-32158-9.

- Minney, R.J. (ed.) The Private Papers of Hore-Belisha London: Collins, 1960.

- Naveh, Shimon, In Pursuit of Military Excellence; The Evolution of Operational Theory. London: Francass, 1997. ISBN 0-7146-4727-6.

- Further reading

External links

- "Defense Is the Best Attack". Time Magazine. 9 October 1939.

- "The Indirect Approach: In Sales Campaigns", a white paper on the application of Liddell Hart's teachings to sales

- Basil Henry Liddell Hart at Find a Grave

|