Azerbaijani language

| Azerbaijani | |

|---|---|

| Azeri, Azeri Turkish, and Azerbaijani Turkish | |

| Azərbaycan dili | |

| Pronunciation | [ɑzærbɑjdʒɑn dili] |

| Native to | |

| Ethnicity | Azerbaijani |

Native speakers | 26 million (1997–2010)[1] |

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

az |

| ISO 639-2 |

aze |

| ISO 639-3 |

aze – inclusive codeIndividual codes: azj – North Azerbaijani azb – South Azerbaijani slq – Salchuq qxq – Qashqai |

| Glottolog |

azer1255 (North Azeri–Salchuq)[2]sout2696 (South Azeri–Qashqa'i)[3] |

| Linguasphere |

part of 44-AAB-a |

|

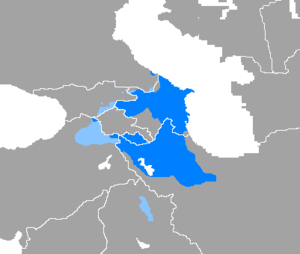

Location of Azerbaijani speakers in the Caucasus regions where Azerbaijani is the language of the majority regions where Azerbaijani is the language of a significant minority | |

| Part of a series on |

| Azerbaijani people |

|---|

| Culture |

| By country or region |

| Religion |

|

| Language |

| Persecution |

|

Azerbaijani (pronunciation: /ˌaːzərbaɪˈdʒɑːni/, /-ˈʒɑːni/),[4][5] Azeri (/aːˈzɛəri/, /əˈ-/),[4][5] Azeri Turkish or Azerbaijani Turkish ([ɑzærbɑjdʒɑn dili]) is a language belonging to the Turkic language family, spoken primarily in the South Caucasus region by the Azerbaijani people also known as Azerbaijani Turks. The language is spoken mainly in Azerbaijan, Iran (especially Iranian Azerbaijan), Georgia, Russia (especially Dagestan Republic) and Turkey, and also in parts of Iraq, Syria and Turkmenistan. North Azerbaijani is spoken in Azerbaijan, where it is the official language, and also southern Dagestan, in the southern Caucasus Mountains and in parts of Central Asia. South Azerbaijani has speakers mainly in the northwest of Iran (also known as Iranian Azerbaijan), where it is known as Türki or Türkü, and also in parts of Iraq and Turkey. Azerbaijani is a member of the Oghuz branch of the Turkic languages. It is closely related to Turkish, Qashqai, Turkmen and Crimean Tatar with which it is, to varying degrees, mutually intelligible.[6]

Etymology

Azerbaijani people in Azerbaijan and Iranian Azerbaijan refer to their language as Türki which literally means Turkish. In 1992–1993, when Azerbaijan Popular Front Party was in power in Azerbaijan, the official language of Azerbaijan was renamed by the parliament as Türk dili ("Turkish"). However, since 1994 the Soviet-era name of the language, Azərbaycan dili ("Azerbaijani"), has been re-established and reflected in the Constitution because of the political reasons. Varlıq, the most important literary Azerbaijani magazine published in Iran, uses the term Türki ("Turkish" in English or "Torki" in Persian) to refer to the Azerbaijani language. Azeris in Iran often refer to the language as Türki, distinguishing it from İstanbul Türki ("Istanbul Turkish"), the official language of Turkey. Some people also consider Azerbaijani to be a dialect of a greater Turkish language and call it Azərbaycan Türkcəsi ("Azerbaijani Turkish or Turkish of Azerbaijan"), and scholars such as Vladimir Minorsky used this definition in their works. ISO encodes its two varieties, North Azerbaijani and South Azerbaijani, as distinct languages. According to the Linguasphere Observatory, all Oghuz languages form part of a single "outer language" of which North and South Azerbaijani are "inner languages".

History and evolution

Today′s Azerbaijani languages evolved from the Eastern Oghuz branch of Western (Oghuz) Turkic[7] which spread to the Caucasus, in Eastern Europe,[8][9] and northern Iran, in Western Asia, during the medieval Turkic migrations, and has been heavily influenced by Persian.[10] Arabic also influenced the language, but Arabic words were mainly transmitted through the intermediary of literary Persian.[11]

Azerbaijani gradually supplanted the Iranian languages in what is now northern Iran, and a variety of Caucasian languages in the Caucasus, particularly Udi. By the beginning of the 16th century, it had become the dominant language of the region, and was a spoken language in the court of the Safavid Empire.

The historical development of Azerbaijani can be divided into two major periods: early (c. 16th to 18th century) and modern (18th century to present). Early Azerbaijani differs from its descendant in that it contained a much larger number of Persian, and Arabic loanwords, phrases and syntactic elements. Early writings in Azerbaijani also demonstrate linguistic interchangeability between Oghuz and Kypchak elements in many aspects (such as pronouns, case endings, participles, etc.). As Azerbaijani gradually moved from being merely a language of epic and lyric poetry to being also a language of journalism and scientific research, its literary version has become more or less unified and simplified with the loss of many archaic Turkic elements, stilted Iranisms and Ottomanisms, and other words, expressions, and rules that failed to gain popularity among the Azerbaijani-speaking masses.

Between c. 1900 and 1930, there were several competing approaches to the unification of the national language in Azerbaijan popularized by the literati, such as Hasan bey Zardabi and Mammad agha Shahtakhtinski. Despite major differences, they all aimed primarily at making it easy for semi-literate masses to read and understand literature. They all criticized the overuse of Persian, Arabic, Ottoman Turkish, and other foreign (mainly Russian) elements in both colloquial and literary language and called for a simpler and more popular style.

The Russian conquest of the South Caucasus in the 19th century split the language community across two states; the Soviet Union promoted development of the language, but set it back considerably with two successive script changes[12] – from Perso-Arabic script to Latin and then to Cyrillic – while Iranian Azerbaijanis continued to use the Perso-Arabic script as they always had. Despite the wide use of Azerbaijani in Azerbaijan during the Soviet era, it became the official language of Azerbaijan only in 1956.[13] After independence, Azerbaijan decided to switch back to the Latin script.

Literature

Classical literature in Azerbaijani was formed in the fifteenth century[14] based on the various Early Middle Ages dialects of Tabriz and Shirvan (these dialects were used by classical Azerbaijani writers Nasimi, Fuzuli, and Khatai). Modern literature in Azerbaijan is based on the Shirvani dialect mainly, while in Iran it is based on the Tabrizi one. The first newspaper in Azerbaijani, Əkinçi was published in 1875.

In mid-19th century it was taught in the schools of Baku, Ganja, Shaki, Tbilisi, and Yerevan. Since 1845, it has also been taught in the University of St. Petersburg in Russia.

Lingua franca

Azerbaijani served as a lingua franca throughout most parts of Transcaucasia (except the Black Sea coast), in Southern Dagestan,[15][16][17] Eastern Turkey, and Iranian Azerbaijan from the 16th century to the early 20th century,[18][19] alongside the cultural, administrative, court literature, and most importantly official language of all these regions, namely Persian.[20] Per the 1829 Caucasus School Statute, Azerbaijani was to be taught in all district schools of Ganja, Shusha, Nukha (present-day Shaki), Shamakhy, Guba, Baku, Derbent, Erivan, Nakhchivan, Akhaltsikhe, and Lankaran. Beginning in 1834, it was introduced as a language of study in Kutaisi instead of Armenian. In 1853, Azerbaijani became a compulsory language for students of all backgrounds in all of the South Caucasus with the exception of the Tiflis Governorate.[21]

Varieties

Azerbaijani language is considered to be a variety of Turkish language. Azerbaijani is sometimes classified as two languages or dialects, North Azerbaijani and South Azerbaijani. Although there is a fair degree of mutual intelligibility between them, there are also morphological and phonological differences. Four varieties have been accorded ISO 639-3 codes: North Azerbaijani, South Azerbaijani, Salchuq, and Qashqai. Glottolog, based on Johanson (2006) and Pakendorf (2007), classifies North Azeri with Salchuq in one branch of the Oghuz languages, and South Azeri with Qashqai in another.

North Azerbaijani

North Azerbaijani,[22] or North Azeri, is the official language of Azerbaijan. It is closely related to the modern Turkish due to the fact that Azerbaijani language is a Turkic language. It is also spoken in southern Dagestan, along the Caspian coast in the southern Caucasus Mountains, and scattered through Central Asia. There are some 7.3 million native speakers, and about 8 million second-language speakers.

The Shirvan dialect is the basis of Standard Azerbaijani. Since 1992, it has been officially written with a Latin/Roman script in Azerbaijan, but the older Cyrillic script was still widely used in the late 1990s.[23]

South Azerbaijani

South Azerbaijani,[24] or South Azeri, is spoken in northwestern Iran and to a lesser extent in neighboring regions of Iraq and Turkey, with smaller communities in Afghanistan and Syria. In Iran, the Persian word for Azerbaijani is Torki,[25] which literally means Turkish; in Azerbaijani it is usually pronounced as Türkü. In Iran, it is spoken in East Azerbaijan and West Azerbaijan, Ardabil, Zanjan, and parts of Kurdistan, Hamadan, Markazi, Qazvin and Gilan. It is also spoken in some districts of Tehran and across Tehran Province. Most sources report the percentage of South Azerbaijani speakers at around 16 percent of the Iranian population, or approximately 16.9 million people worldwide.[26]

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n̪ | ||||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t̪ | d̪ | t͡ʃ | d͡ʒ | c | ɟ | k | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | f | v | s̪ | z̪ | ʃ | ʒ | x | ɣ | h | |||

| Approximant | l | j | ||||||||||

| Tap | ɾ | |||||||||||

- /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ are realised as [t͡s] and [d͡z] respectively in the areas around Tabriz and to the west, south and southwest of Tabriz (including Kirkuk in Iraq); in the Nakhchivan and Ayrum dialects, in Cəbrayil and some Caspian coastal dialects;[27]

- In most dialects of Azerbaijani, /c/ is realized as [ç] when it is found in the coda position or is preceded by a voiceless consonant (as in çörək [t͡ʃøˈɾæç] – "bread"; səksən [sæçˈsæn] – "eighty").

- /k/ appears only in words borrowed from Russian or French (spelled, as with /c/, with a k).

- /w/ exists in the Kirkuk dialect as an allophone of /v/ in Arabic loanwords.

- In the Baku dialect, /ov/ may be realised as [oʊ], and /ev/ and /øv/ as [œy], e.g. /ɡovurˈmɑ/ → [ɡoʊrˈmɑ], /sevˈdɑ/ → [sœyˈdɑ], /dœvˈrɑn/ → [dœyˈrɑn], as well as with surnames ending in -ov/-ev (borrowed from Russian).[28]

- In the colloquial language, /x/ is usually pronounced as [χ]

Vowels

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unr. | Rnd. | Unr. | Rnd. | |

| Close | i | y | ɯ | u |

| Mid | e | ø | o | |

| Open | æ | ɑ | ||

The vowels of the Azerbaijani language are, in their alphabetical order, a, e, ə, ı, i, o, ö, u, ü. There are no diphthongs in Azerbaijani when two vowels come together; when that occurs in some Arabic loanwords, each vowel retains its individual sound.

Writing system and alphabets

Before 1929, Azerbaijani was written only in the Perso-Arabic script. In 1929–1938 a Latin alphabet was in use for North Azerbaijani (although it was different from the one used now), from 1938 to 1991 the Cyrillic script was used, and in 1991 the current Latin alphabet was introduced, although the transition to it has been rather slow. In Iran, Azerbaijani is still written in Perso-Arabic script.

Perso-Arabic and Cyrillic alphabets do not have marked vowels making it hard to write proper Azerbaijani sounds. Perso-Arabic and Cyrillic alphabets and letters are not fitting the Azerbaijani pronunciation and the Latin alphabet needed some extra adaptations such as ğ and ı. The Azerbaijani Latin alphabet is based on the Turkish Latin alphabet because of their linguistic connections and mutual intelligibility. Әə, Xx, and Qq, the letters are available only in Azerbaijani for sounds which do not exist as separate phonemes in Turkish. Keep in mind that the letter "c" in Azerbaijani and Turkish pronounced like English j in the word jam, "j" pronounced like English s in the word measure, and "ç" is pronounced like English ch in the word chat.

The following letters are in Latin (Azerbaijan since 1991) & Perso-Arabic (Iran; Azerbaijan until 1922).

- Aa ﺍ

- - short as in 'along' or long as in 'army'.

- Bb ﺏ

- - pronounced like 'b' in 'bell'.

- Cc ﺝ

- - pronounced like 'J' in Japan.

- Çç چ

- - pronounced like 'ch' in chat..

- Dd ﺩ

- - pronounced like 'd' in dog; otherwise, like 'th' in 'the'.

- Ee ﻩ

- - pronounced like soft 'e' in Embassy. This can be long as in 'bate'.

- Əə ع

- - pronounced like 'a' in fat. (This letter was represented by Ää from 1991-1992). This is long as in 'bate' or 'cape'.

- Ff ﻑ

- - pronounced like 'f' in 'fold'.

- Gg گ

- - pronounced like hard 'g' in goal.

- Ğğ ﻍ

- - pronounced at the back of throat like the French 'r'

- Hh ﺡ / ﻩ

- - pronounced like 'h' in 'hat'.

- Xx ﺥ

- - pronounced like 'Spanish j' (or 'Persian kh').

- Iı ی

- - pronounced like 'u' in 'butter' or 'Sutton'.

- İi ی

- - pronounced like 'i' in 'pit'. This can be 'ee' as in 'meet'.

- Jj ژ

- - pronounced like 'j' (or 'zh') in déjà vu.

- Kk ک

- - pronounced like 'k' in 'kill'.

- Qq ﻕ

- - pronounced like 'q' in 'Qatar'; usually a slide between 'g' in 'goal' and 'k' in 'kill'.

- Ll ﻝ

- - pronounced like 'l' in 'Lauren'

- Mm ﻡ

- - pronounced like 'm' in 'Mom'.

- Nn ﻥ

- - pronounced like 'n' in 'noon'.

- Oo ﻭ

- - pronounced like 'o' in note.

- Öö ﻭ

- - same as in 'German Ö' and 'Turkish Ö'.

- Pp پ

- - pronounced like 'p' in Police.

- Rr ﺭ

- - Roll you r's!

- Ss ﺙ / ﺱ / ﺹ

- - pronounced like 's' in sizzle.

- Şş ﺵ

- - pronounced like 'sh' in shape.

- Tt ﺕ / ﻁ

- - pronounced like 't' in tape.

- Uu ﻭ

- - pronounced like 'u' in put.

- Üü ﻭ

- - pronounced like 'Turkish Ü'.

- Vv ﻭ

- - pronounced like 'v' in 'van'; otherwise, like 'w' in 'world'.

- Yy ی

- - pronounced like 'y' in year.

- Zz ﺫ / ﺯ / ﺽ / ﻅ

- - pronounced like 'z' in zebra, same as 's' in 'nose' or 'his'.

Vocabulary

Notice that Azerbaijani has informal and formal ways of saying things. This is because there is more than one meaning to "you" in Turkic languages like Azerbaijani and Turkish (as well as in many other languages). The informal you is used when talking to close friends, relatives, animals or children. The formal you is used when talking to someone who is older than you or someone for whom you would like to show respect (a professor, for example). As in many Romance languages, personal pronouns can be omitted, and they are only added for emphasis. Azerbaijani is a very phonetic language, so pronunciation is very easy. Most words are pronounced exactly as they are spelled.

| Category | English | Azerbaijani |

|---|---|---|

| Basic expressions | yes | hə /hæ/ |

| no | yox /jox/ | |

| hello | salam /sɑlɑm/ | |

| goodbye | sağ ol /ˈsɑɣ ol/ | |

| sağ olun /ˈsɑɣ olun/ (formal) | ||

| good morning | sabahınız xeyir /sɑbɑhı(nı)z xejiɾ/ | |

| good afternoon | günortanız xeyir /ɟynoɾt(ɯn)ɯz xejiɾ/ | |

| good evening | axşamın xeyir /ɑxʃɑmɯn xejiɾ/ | |

| axşamınız xeyir /ɑxʃɑmɯ(nɯ)z xejiɾ/ | ||

| Colours | black | qara /gɑɾɑ/ |

| blue | göy /ɟœj/ | |

| cyan | mavi /mɑːvi/ | |

| brown | qəhvəyi/qonur | |

| grey | boz /boz/ | |

| green | yaşıl /jaʃɯl/ | |

| orange | narıncı /nɑɾɯnd͡ʒɯ/ | |

| pink | çəhrayı | |

| purple | bənövşəyi | |

| red | qırmızı /gɯɾmɯzɯ/ | |

| white | ağ /ɑɣ/ | |

| yellow | sarı /sɑɾɯ/ |

Numbers

| Number | Word |

|---|---|

| 0 | sıfır /ˈsɯfɯɾ/ |

| 1 | bir /biɾ/ |

| 2 | iki /ici/ |

| 3 | üç /yt͡ʃ/ |

| 4 | dörd /dœɾd/ |

| 5 | beş /beʃ/ |

| 6 | altı /ɑltɯ/ |

| 7 | yeddi /jetti/ |

| 8 | səkkiz /sæcciz/ |

| 9 | doqquz /dokkuz/ |

| 10 | on /on/ |

For numbers 11–19, the numbers literally mean "10 one, 10 two" and so on.

| Number | Word |

|---|---|

| 20 | iyirmi /ijiɾmi/ |

| 30 | otuz /otuz/ |

| 40 | qırx /gɯɾx/ |

| 50 | əlli /ælli/ |

See also

- Historical linguistics

- Language families and languages

Notes

References

- ↑ Azerbaijani at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

North Azerbaijani at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

South Azerbaijani at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Salchuq at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Qashqai at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "North Azeri–Salchuq". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "South Azeri–Qashqa'i". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Roach, Peter (2011), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521152532

- ↑ Sinor, Denis (1969). Inner Asia. History-Civilization-Languages. A syllabus. Bloomington. pp. 71–96. ISBN 0-87750-081-9.

- ↑ "The Turkic Languages", Osman Fikri Sertkaya (2005) in Turks – A Journey of a Thousand Years, 600-1600, London ISBN 978-1-90397-356-1

- ↑ Wright, Sue; Kelly, Helen (1998). Ethnicity in Eastern Europe: Questions of Migration, Language Rights and Education. Multilingual Matters Ltd. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-85359-243-0.

- ↑ Bratt Paulston, Christina; Peckham, Donald (1 October 1998). Linguistic Minorities in Central and Eastern Europe. Multilingual Matters Ltd. pp. 98–115. ISBN 978-1-85359-416-8.

- ↑ L. Johanson, "AZERBAIJAN ix. Iranian Elements in Azeri Turkish" in Encyclopædia Iranica .

- ↑ John R. Perry, "Lexical Areas and Semantic Fields of Arabic" in Csató et al. (2005) Linguistic convergence and areal diffusion: case studies from Iranian, Semitic and Turkic, Routledge, p. 97: "It is generally understood that the bulk of the Arabic vocabulary in the central, contiguous Iranic, Turkic and Indic languages was originally borrowed into literary Persian between the ninth and thirteenth centuries CE ..."

- ↑ "Alphabet Changes in Azerbaijan in the 20th Century". Azerbaijan International. Spring 2000. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ Language Commission Suggested to Be Established in National Assembly. Day.az. 25 January 2011.

- ↑ Mark R.V. Southern. Mark R V Southern (2005) Contagious couplings: transmission of expressives in Yiddish echo phrases, Praeger, Westport, Conn. ISBN 978-0-31306-844-7

- ↑ Pieter Muysken, "Introduction: Conceptual and methodological issues in areal linguistics", in Pieter Muysken (2008) From Linguistic Areas to Areal Linguistics, p. 30-31 ISBN 90-272-3100-1

- ↑ Viacheslav A. Chirikba, "The problem of the Caucasian Sprachbund" in Muysken, p. 74

- ↑ Lenore A. Grenoble (2003) Language Policy in the Soviet Union, p. 131 ISBN 1-4020-1298-5

- ↑ Nikolai Trubetzkoy (2000) Nasledie Chingiskhana, p. 478 Agraf, Moscow ISBN 978-5-77840-082-5 (Russian)

- ↑ J. N. Postgate (2007) Languages of Iraq, p. 164, British School of Archaeology in Iraq ISBN 0-903472-21-X

- ↑ Homa Katouzian (2003) Iranian history and politics, Routledge, pg 128: "Indeed, since the formation of the Ghaznavids state in the tenth century until the fall of Qajars at the beginning of the twentieth century, most parts of the Iranian cultural regions were ruled by Turkic-speaking dynasties most of the time. At the same time, the official language was Persian, the court literature was in Persian, and most of the chancellors, ministers, and mandarins were Persian speakers of the highest learning and ability"

- ↑ "Date of the Official Instruction of Oriental Languages in Russia" by N.I.Veselovsky. 1880. in W.W. Grigorieff ed. (1880) Proceedings of the Third Session of the International Congress of Orientalists, Saint Petersburg (Russian)

- ↑ "Azerbaijani, North – A language of Azerbaijan" Ethnologue, accessed 8 December 2008

- ↑ Schönig (1998), pg. 248.

- ↑ "Azerbaijani, South – A language of Iran" Ethnologue, accessed 8 December 2008

- ↑ "Azerbaijani, South". Ethnologue. 1999-02-19. Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- ↑ Persian Studies in North America by Mohammad Ali Jazayeri

- ↑ Shiraliyev, Mammadagha. The Baku Dialect. Azerbaijan SSR Academy of Sciences Publ.: Baku, 1957; p. 41

External links

| Azerbaijani edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Azerbaijani. |

| Azerbaijani language test of Wikinews at Wikimedia Incubator |

| South Azerbaijani test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- A blog on Azerbaijani language resources and translations

- (Russian) A blog about the Azerbaijani language and lessons

- azeri.org, Azerbaijani literature and English translations.

- Online bidirectional Azerbaijani-English Dictionary

- Learn Azerbaijani at learn101.org.

- Pre-Islamic roots

- Azerbaijan-Turkish language in Iran by Ahmad Kasravi.

- Azerbaijan tongue with Japanese translation at the Wayback Machine (archived 14 October 2007) including sound file.

- Azerbaijan-Turkish and Turkish-Azerbaijan dictionary

- Azerbaijani<>Turkish dictionary (Pamukkale University)

- Azerbaijan Language with Audio

- Azerbaijani thematic vocabulary

- AzConvert, an open source Azerbaijani transliteration program.

- Azerbaijani Alphabet and Language in Transition, the entire issue of Azerbaijan International, Spring 2000 (8.1) at azer.com.

- Learn the easiest Turkic dialect: Azerbaijani lessons with video and grammar notes in English, phrasebooks in Spanish, Italian and Hungarian.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||