Axiom of determinacy

The axiom of determinacy (abbreviated as AD) is a possible axiom for set theory introduced by Jan Mycielski and Hugo Steinhaus in 1962. It refers to certain two-person games of length ω with perfect information. AD states that every such game in which both players choose natural numbers is determined; that is, one of the two players has a winning strategy.

The axiom of determinacy is inconsistent with the axiom of choice (AC); the axiom of determinacy implies that all subsets of the real numbers are Lebesgue measurable, have the property of Baire, and the perfect set property. The last implies a weak form of the continuum hypothesis (namely, that every uncountable set of reals has the same cardinality as the full set of reals).

Furthermore, AD implies the consistency of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory (ZF). Hence, as a consequence of the incompleteness theorems, it is not possible to prove the relative consistency of ZF + AD with respect to ZF.

Types of game that are determined

Not all games require the axiom of determinacy to prove them determined. Games whose winning sets are closed are determined. These correspond to many naturally defined infinite games. It was shown in 1975 by Donald A. Martin that games whose winning set is a Borel set are determined. It follows from the existence of sufficient large cardinals that all games with winning set a projective set are determined (see Projective determinacy), and that AD holds in L(R).

Incompatibility of the axiom of determinacy with the axiom of choice

The set S1 of all first player strategies in an ω-game G has the same cardinality as the continuum. The same is true of the set S2 of all second player strategies. We note that the cardinality of the set SG of all sequences possible in G is also the continuum. Let A be the subset of SG of all sequences which make the first player win. With the axiom of choice we can well order the continuum; furthermore, we can do so in such a way that any proper initial portion does not have the cardinality of the continuum. We create a counterexample by transfinite induction on the set of strategies under this well ordering:

We start with the set A undefined. Let T be the "time" whose axis has length continuum. We need to consider all strategies {s1(T)} of the first player and all strategies {s2(T)} of the second player to make sure that for every strategy there is a strategy of the other player that wins against it. For every strategy of the player considered we will generate a sequence which gives the other player a win. Let t be the time whose axis has length ℵ0 and which is used during each game sequence.

- Consider the current strategy {s1(T)} of the first player.

- Go through the entire game, generating (together with the first player's strategy s1(T)) a sequence {a(1), b(2), a(3), b(4),...,a(t), b(t+1),...}.

- Decide that this sequence does not belong to A, i.e. s1(T) lost.

- Consider the strategy {s2(T)} of the second player.

- Go through the next entire game, generating (together with the second player's strategy s2(T)) a sequence {c(1), d(2), c(3), d(4),...,c(t), d(t+1),...}, making sure that this sequence is different from {a(1), b(2), a(3), b(4),...,a(t), b(t+1),...}.

- Decide that this sequence belongs to A, i.e. s2(T) lost.

- Keep repeating with further strategies if there are any, making sure that sequences already considered do not become generated again. (We start from the set of all sequences and each time we generate a sequence and refute a strategy we project the generated sequence onto first player moves and onto second player moves, and we take away the two resulting sequences from our set of sequences.)

- For all sequences that did not come up in the above consideration arbitrarily decide whether they belong to A, or to the complement of A.

Once this has been done we have a game G. If you give me a strategy s1 then we considered that strategy at some time T = T(s1). At time T, we decided an outcome of s1 that would be a loss of s1. Hence this strategy fails. But this is true for an arbitrary strategy; hence the axiom of determinacy and the axiom of choice are incompatible.

Infinite logic and the axiom of determinacy

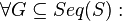

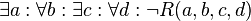

Many different versions of infinitary logic were proposed in the late 20th century. One reason that has been given for believing in the axiom of determinacy is that it can be written as follows (in a version of infinite logic):

OR

OR

Note: Seq(S) is the set of all  -sequences of S. The sentences here are infinitely long with a countably infinite list of quantifiers where the ellipses appear.

-sequences of S. The sentences here are infinitely long with a countably infinite list of quantifiers where the ellipses appear.

In an infinitary logic, this principle is therefore a natural generalization of the usual (de Morgan) rule for quantifiers that

are true for finite formulas, such as  OR

OR  .

.

Large cardinals and the axiom of determinacy

The consistency of the axiom of determinacy is closely related to the question of the consistency of large cardinal axioms. By a theorem of Woodin, the consistency of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory without choice (ZF) together with the axiom of determinacy is equivalent to the consistency of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory with choice (ZFC) together with the existence of infinitely many Woodin cardinals. Since Woodin cardinals are strongly inaccessible, if AD is consistent, then so are an infinity of inaccessible cardinals.

Moreover, if to the hypothesis of an infinite set of Woodin cardinals is added the existence of a measurable cardinal larger than all of them, a very strong theory of Lebesgue measurable sets of reals emerges, as it is then provable that the axiom of determinacy is true in L(R), and therefore that every set of real numbers in L(R) is determined.

See also

- Axiom of real determinacy (ADR)

- AD+, a variant of the axiom of determinacy formulated by Woodin

- Axiom of quasi-determinacy (ADQ)

- Martin measure

References

- Jech, Thomas (2002). Set theory, third millennium edition (revised and expanded). Springer. ISBN 3-540-44085-2.

- Kanamori, Akihiro (2000). The Higher Infinite (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 3-540-00384-3.

- Martin, Donald A.; Steel, John R. (Jan 1989). "A Proof of Projective Determinacy". Journal of the American Mathematical Society 2 (1): 71–125. doi:10.2307/1990913. JSTOR 1990913.

- Moschovakis, Yiannis N. (1980). Descriptive Set Theory. North Holland. ISBN 0-444-70199-0.

- Mycielski, Jan; Steinhaus, H. (1962). "A mathematical axiom contradicting the axiom of choice". Bulletin de l'Académie Polonaise des Sciences. Série des Sciences Mathématiques, Astronomiques et Physiques 10: 1–3. ISSN 0001-4117. MR 0140430.

- Woodin, W. Hugh (1988). "Supercompact cardinals, sets of reals, and weakly homogeneous trees". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 85 (18): 6587–6591. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.18.6587. PMC 282022. PMID 16593979.