Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney

| Polycystic Kidney Disease | |

|---|---|

Polycystic kidneys | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | Q61 |

| ICD-9 | 753.1 |

| OMIM | 601313 173910 |

| DiseasesDB | 10262 |

| MedlinePlus | 000502 |

| eMedicine | radio/68 |

| MeSH | D016891 |

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease ("ADPKD", "autosomal dominant PKD" or "Adult-onset PKD") is an inherited systemic disorder that predominantly affects the kidneys, but may affect other organs including the liver, pancreas, brain, and arterial blood vessels. Approximately 50% of people with this disease will develop end stage kidney disease and require dialysis or kidney transplantation. Progression to end stage kidney disease usually happens in the 4th to 6th decades of life.[1] Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease occurs worldwide and affects about 1 in 400 to 1 in 1000 people.[2][3]

Defects in two genes are thought to be responsible for ADPKD. In 85% of patients, ADPKD is caused by mutations in the gene PKD1 on chromosome 16 (TRPP1); in 15% of patients mutations in PKD2 (TRPP2) are causative.[1]

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease is a distinct disease that also leads to cysts in the kidneys and liver, typically presents in childhood, only affects about 1 in 20,000 people[4] and has different causes and prognosis.

Pathophysiology

Recent studies in fundamental cell biology of cilia and flagella using experimental model organisms such as the round worm Caenorhabditis elegans and the mouse Mus musculus have shed light on how PKD develops in human patients.[5]

All cilia and flagella are constructed and maintained by the process of intraflagellar transport, a cellular function that is also essential for the insertion of proteins at specific sites along cilia and flagella membranes. These inserted membrane proteins can initiate environmental sensing and intracellular signaling pathways. They play a special role in the cilia of renal epithelial cells, and are thought to be critical for normal renal cell development and function and are sorted out and localized to the cilia of renal epithelial cells by the aforementioned intraflagellar transport mechanism. Ciliated epithelial cells line the lumen of the urinary collecting ducts and sense the flow of urine. Failure in flow-sensing signaling results in proliferation of these renal epithelial cells, producing the characteristic multiple cysts of PKD. PKD may result from mutations of signaling and environmental sensing proteins, or failure in intraflagellar transport.[6]

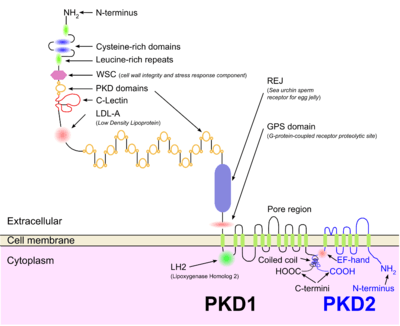

Two PKD genes, PKD1 and PKD2, encode membrane proteins that localize to a non-motile cilium on the renal tube cell. Polycystin-2 encoded by PKD2 gene is a calcium channel that allows extracellular calcium ions to enter the cell. Polycystin-1, encoded by PKD1 gene, is thought to be associated with polycystin-2 protein and regulates polycystin-2's channel activity. The calcium ions are important cellular messengers, which trigger complicated biochemical pathways that lead to quiescence and differentiation. Malfunctions of polycystin-1 or polycystin-2 proteins, defects in the assembly of the cilium on the renal tube cell, failures in targeting these two proteins to the cilium, and deregulations of calcium signaling all likely cause the occurrence of PKD.

Genetics

As stated above, defects in two genes are thought to be responsible for ADPKD. In 85% of patients, ADPKD is caused by mutations in the gene PKD1 on chromosome 16 (TRPP1); in 15% of patients mutations in PKD2 (TRPP2) are causative.[1][7]

PKD and the "two hit" hypothesis

The two hit hypothesis (aka Knudson hypothesis ) is often used to explain the manifestation of polycystic kidney disease later in life even though the mutation is present at birth. This term is borrowed from cancer research stating that both copies of the gene present in the genome have to be "silenced" before cancer manifests itself (in Knudson's case the silenced gene was Rb1). In ADPKD the original "hit" is congenital (in either the PKD1 or PKD2 genes) and the subsequent "hit" occurs later in life as the cells grow and divide. The two hit hypothesis as it relates to PKD was originally proposed by Reeders in 1992.[8] Support for this hypothesis comes from the fact that ARPKD patients develop disease at birth, and somatic mutations in the "normal" copy of PKD1 or PKD2 have been found in cyst-lining epithelia

Relation to other rare genetic disorders

Recent findings in genetic research have suggested that a large number of genetic disorders, both genetic syndromes and genetic diseases, that were not previously identified in the medical literature as related, may be, in fact, highly related in the genetypical root cause of the widely varying, phenotypically-observed disorders. Thus, PKD is a ciliopathy. Other known ciliopathies include primary ciliary dyskinesia, Bardet-Biedl syndrome, polycystic liver disease, nephronophthisis, Alstrom syndrome, Meckel-Gruber syndrome, and some forms of retinal degeneration.[9]

Diagnosis

A definite diagnosis of ADPKD relies on imaging or molecular genetic testing. The sensitivity of testing is nearly 100% for all patients with ADPKD who are age 30 years or older and for younger patients with PKD1 mutations; these criteria are only 67% sensitive for patients with PKD2 mutations who are younger than age 30 years. Large echogenic kidneys without distinct macroscopic cysts in an infant/child at 50% risk for ADPKD are diagnostic. In the absence of a family history of ADPKD, the presence of bilateral renal enlargement and cysts, with or without the presence of hepatic cysts, and the absence of other manifestations suggestive of a different renal cystic disease provide presumptive, but not definite, evidence for the diagnosis.

Molecular genetic testing by linkage analysis or direct mutation screening is available clinically; however, genetic heterogeneity is a significant complication to molecular genetic testing. Sometimes a relatively large number of affected family members need to be tested in order to establish which one of the two possible genes is responsible within each family. The large size and complexity of PKD1 and PKD2 genes, as well as marked allelic heterogeneity, present obstacles to molecular testing by direct DNA analysis. In the research setting, mutation detection rates of 50-75% have been obtained for PKD1 and ~75% for PKD2. Clinical testing of the PKD1 and PKD2 genes by direct sequence analysis is now available, with a detection rate for disease-causing mutations of 50-70%.

Genetic counseling may be helpful for families at risk for polycystic kidney disease.

Treatment

While limited medications and research into other treatments have recently been showing promise, Polycystic Kidney Disease currently has no cure. However, some treatment options are available, ranging from symptomatic to attempting to delay the onset of end-stage renal failure (such as blood pressure control, etc.).

Renal cysts often become excessively enlarged and causes intra-abdominal pressure and pain. Symptomatic cysts and complex renal cysts often need intervention in order to alleviate pain. Such intervention can take various forms, ranging from analgesic medication, percutaneous ultrasound guided needle aspiration, with or without sclerotherapy, laparoscopic or open surgical cyst deroofing, total or partial nephrectomy,[10] dialysis, to kidney transplant.

Analgesic Medication

Over-the-counter pain medications, such as paracetamol (acetaminophen) can relieve pain.

Renal cyst aspiration

Aspiration with Sclerotherapy for symptomatic simple renal cysts is simple, minimally invasive and is claimed to be highly effective. It is often recommend as the first therapeutic option in patients with symptomatic renal cysts.[11] Renal cyst aspiration alone consists of the insertion of a needle into the identified cyst, under ultrasound guidance, and draining the cyst liquid. However, without sclerotherapy, cyst reaccumulation with symptom recurrence is common. Currently, in many instances, first-line therapy for symptomanitc simple renal cysts is aspiration in combination with sclerotherapy.[12][13] The instillation of a sclerosing agent into a renal cyst following aspiration significantly reduces the rate of recurrence. Response rates of 77% to 97% have been reported. Reports have also suggested that multiple sclerotherapy treatments may increase the success rate of the treatment.[12][13] 95% ethanol, 1–3% sodium tetradecyl sulphate, 50% acetic acid, 10% ethanolamine oleate and bismuth phosphate are the sclerosants usually used.[10]

Laparoscopic cyst deroofing

Laparoscopic cyst deroofing (also referred to as decortication/marsupialization)[10] entails laparoscopic surgery in order to surgically remove one or more kidney cysts. Such surgery is usually only indicated after earlier cyst aspiration has confirmed that the cyst is responsible for pain.[14] Laparoscopic deroofing is rapidly becoming accepted as the surgical intervention of choice for symptomatic renal cysts persisting after aspiration sclerotherapy.[10] The process consist of the insertion of four laparoscopic ports, the camera and instruments into the abdominal cavity, where a workspace is created. The relevant kidney and identified kidney cyst(s) is located and the top of the cyst is removed by cutting a hole in the cyst wall, releasing all the fluid.[15][16]

In a non-randomised controlled trial of patients with symptomatic simple renal cysts, who had recurrence of symptoms after initial response to simple aspiration, pain recurred in all five patients treated with cyst aspiration and sclerotherapy at a mean follow-up of 17 months, whereas all seven patients treated with laparoscopic deroofing were pain-free at a mean follow-up of 17.7 months. Laparoscopic renal cyst deroofing is therefore very effective and current evidence on the safety and efficacy of laparoscopic deroofing of simple renal cysts is adequate to support the use of this procedure.[10][17]

In another comparative study of patients with symptomatic simple renal cyst, 52 patients underwent ultrasound guided percutaneous aspiration sclerotherapy and 20 patients underwent laparoscopic deroofing of simple renal cysts. Laparoscopic deroofing of renal cysts demonstrated only a 5% recurrence rate compared with an 82% recurrence rate for sclerotherapy. In contrast to the above results, it is interesting that most case series on aspiration sclerotherapy claim high success rate.[10][18]

Nephrectomy

In severe cases, nephrectomy may be advised. Nephrectomy is the surgical removal of a kidney. There are various indications for this procedure, such as a non-functioning kidney (which may cause high blood pressure).

Dialysis

Dialysis is a process for removing waste and excess water from the blood, and is used primarily as an artificial replacement for lost kidney function in people with renal failure. Dialysis treatments replace some of the kidneys’ functions through diffusion (waste removal) and ultrafiltration (fluid removal).

Kidney Transplant

Kidney transplantation or renal transplantation is the surgical organ transplant of a kidney into a patient with end-stage renal disease.

Research directions

Vasopressin suppression (Tolvaptan)

It is known that the molecule cAMP is involved in the enlargement of kidney cysts in PKD kidneys.[19] Various studies on rodents have shown that a hormone, called vasopressin, increases levels of cAMP in the body. When mice with PKD were given a chemical that blocks vasopressin, there was an impressive decrease in kidney size and some preservation of kidney function. Similarly, when studied mice consumed excessive amounts of water (which decreases levels of vasopressin), a similar result was seen. It has therefore been suggested that consuming large amounts of water may possibly assist in the treatment of early stage PKD.[20][21]

As humans do not always mimic rodents in clinical trials, it is currently not yet certain whether vasopressin inhibitors, such as water, will have corresponding results in humans, or what negative effects excessive water intake may have on the kidneys of individuals with PKD. Clinical trials are currently underway in this field.[22]

It has also been suggested that treatment with medications inhibiting vasopressin may assist in the management of PKD and reduce the speed at which kidney cysts form and grow, delaying the onset of end stage renal failure. Clinical trials are currently underway in the testing of Tolvaptan, a U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved medication which has not yet been approved for use in the treatment of PKD.[23] Studies have shown that ADPKD cyst growth progresses more slowly with Tolvaptan. However, adverse effects appear to be common.[24][25]

USA

In April 2013, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. announced that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has accepted for priority review the company's new drug application for the potential use of Tolvaptan for the treatment of ADPKD. Phase III clinical trial results that form the basis of the regulatory filing were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.[26][27] However, in August 2013, the FDA sent a complete response letter to the company indicating that it "cannot approve the application in its present form" and requesting "additional information".[28][29] Otsuka's chief strategic officer indicated that it was evaluating the content of the FDA's response and will work closely with the agency to determine if there are viable paths forward to address its outstanding questions.[28]

EU

In December 2013 Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. announced that the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has accepted the submission of a marketing authorisation application (MAA) for the potential approval of Tolvaptan for the treatment of ADPKD.[30]

Japan

In March 2014, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. announced that it has become the first company in the world to obtain regulatory approval for a pharmacological treatment of ADPKD. Samsca (generic name: Tolvaptan) has been approved in Japan in 7.5-mg and 15-mg tablet forms for extended use for the additional indication of ADPKD. Also, the new dosage form of 30-mg Samsca tablets has received approval for the indication of ADPKD.[31]

Vitamin B3

Recently, Xiaogang Li, Ph.D., an associate professor of Nephrology and Hypertension and a member of the KU Kidney Institute, found that vitamin B3 helped naturally inhibit the activity of the protein Sirtuin 1 (encoded by the Sirt1 gene) that influences the formation and growth of cysts.[32] Li and colleagues were able to show that vitamin B3 slowed the creation of cysts and restored kidney function in mice with PKD. The results were published in the June 17, 2013 Journal of Clinical Investigation.[33]

Because vitamin B3 is a commonly used supplement with little reported toxicity, Li hopes that efforts to test its effectiveness might bypass the early phase clinical trials that test toxicity in humans. "Promising therapies with vitamin B3 might rapidly be translated into human phase III clinical trials without years of normally required drug testing," Li says. Li believes that administration of Vitamin B3 to a neonate, toddler or adolescent will effectively prevent or delay cyst formation and can be used for a lifetime.

Niacin VS Nicotinamide

Vitamin B3 comes in two principal forms: niacin (nicotinic acid) and nicotinamide (niacinamide). When taken in low doses for nutritional purposes, these two forms of the vitamin are essentially identical. However, each has its own particular effects when taken in high doses.[34][35] Online sources referring to the therapeutic potential of Vitamin B3 in relation to ADPKD are inconsistent regarding whether the most effective form of Vitamin B3 is Niacin[36][37][38][39] or Nicotinamide.[40][41][42][43] However, Sirtuin proteins are known to be inhibited by nicotinamide,.[40][43] The original published article by Li and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Investigation also expressly refers to nicotinamide, as opposed to niacin.[40]

Naringenin

One study has indicated that a natural product found in grapefruit may prevent kidney cysts from forming.[44][45][46] Naringenin, which is also present in other citrus fruits, has been found to successfully block the formation of kidney cysts, by regulating the PKD2 protein, which is one of the genes responsible for the condition. For their research, the team conducted an experiment on a single-celled amoeba containing a protein called Polycystin-2 which is coded by the PKD2 gene. This is one of the proteins associated with the development of ADPKD. It was discovered that when naringenin came into contact with the PKD2 protein, it became regulated, blocking the formation of cysts.[46]

Prognosis

Despite significant research, prognosis of this disease has changed little over time. It is suggested that avoidance of caffeine may prevent cyst formation. Although not well-proven, treatment of hypertension and a low protein diet may slow progression of the disease.

Between PKD1 and PKD2, the former has the worse prognosis.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Grantham, Jared (Oct 2, 2008). "Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease". New England Journal of Medicine 359 (14): 1477–1485. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0804458. PMID 18832246.

- ↑ Torres, Vicente; Harris, Peter C (20 May 2009). "Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the last 3 years". Kidney International 76 (2): 149–168. doi:10.1038/ki.2009.128. PMC 2812475. PMID 19455193.

- ↑ DALGAARD OZ (1957). "Bilateral polycystic disease of the kidneys; a follow-up of two hundred and eighty-four patients and their families". Acta Med. Scand. Suppl. 328: 1–255. PMID 13469269.

- ↑ Zerres K, Mücher G, Becker J et al. (1998). "Prenatal diagnosis of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD): molecular genetics, clinical experience, and fetal morphology". Am. J. Med. Genet. 76 (2): 137–44. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19980305)76:2<137::AID-AJMG6>3.0.CO;2-Q. PMID 9511976.

- ↑ Calvet, James P. (Oct 2002). "Cilia in PKD—Letting It All Hang Out". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 13 (10): 2614–16. PMID 12239253.

- ↑ Yoder BK, Hou X, Guay-Woodford LM (Oct 2002). "The Polycystic Kidney Disease Proteins, Polycystin-1, Polycystin-2, Polaris, and Cystin, Are Co-Localized in Renal Cilia". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 13 (10): 2508–2516. doi:10.1097/01.ASN.0000029587.47950.25. PMID 12239239.

- ↑ First Aid for the USMLE. 2011, pg. 472

- ↑ Reeders ST (1992). "Multilocus polycystic disease". Nat. Genet. 1 (4): 235–7. doi:10.1038/ng0792-235. PMID 1338768.

- ↑ Badano, Jose L.; Norimasa Mitsuma; Phil L. Beales; Nicholas Katsanis (September 2006). "The Ciliopathies : An Emerging Class of Human Genetic Disorders". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 7: 125–148. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. PMID 16722803.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Laparoscopic Deroofing of Large Renal Simple Cysts Causing Gastric Symptoms

- ↑ Treatment of symptomatic simple renal cysts by percu... [BJU Int. 2005] - PubMed - NCBI

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Smith's Textbook of Endourology - Google Books

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Smith's Textbook of Endourology, edited by Arthur D. Smith

- ↑ http://www.cuh.org.uk/cms/sites/default/files/publications/PIN0591_laparoscopic_de-roofing_of_simple_renal_cyst.pdf

- ↑ cyst-deroofing

- ↑ Laparoscopic deroofing of simple renal cysts

- ↑ Consonni P, Nava L, Scattoni V, Bianchi A, Spaliviero M, Guazzoni G, Bellinzoni P, Bocciardi A, Rigatti P, Arch Ital Urol Androl. 1996 Dec; 68(5 Suppl):27-30.

- ↑ Okeke AA, Mitchelmore AE, Keeley FX, Timoney AG, BJU Int. 2003 Oct; 92(6):610-3.

- ↑ "cAMP Regulates Cell Proliferation and Cyst Formation in Autosomal Polycystic Kidney Disease Cells". Jasn.asnjournals.org. 2000-07-01. Retrieved 2012-02-16.

- ↑ Welcome to the Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD) Charity UK

- ↑ http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/content/4/6/1140.full.pdf

- ↑ "High Water Intake to Slow Progression of Polycystic Kidney Disease - Full Text View". ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved 2012-02-16.

- ↑ "Otsuka Maryland Research Institute, Inc. Granted Fast Track Designation For Tolvaptan In PKD". Medicalnewstoday.com. Retrieved 2012-02-16.

- ↑ Tolvaptan in autosomal dominant polycy... [Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011] - PubMed - NCBI

- ↑ CLINJASN | Mobile

- ↑ Otsuka's New Drug Application for Tolvaptan, the Investigational Compound for Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD), Accepted for Review by the US Food and Drug...

- ↑ N Engl J Med 2012; 367:2407-2418December 20, 2012DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205511 : http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1205511

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 FDA turns down Otsuka's kidney disease candidate - PMLiVE

- ↑ FDA Responds to Tolvaptan New Drug Application - PKD Foundation

- ↑ European Medicines Agency (EMA) Accepts Otsuka's Marketing Authorisation Application (MAA) for Tolvaptan, an Investigational Compound for Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney ...

- ↑ Otsuka Pharmaceutical's Samsca® Approved in Japan as the World's First Drug Therapy for ADPKD, a Rare Kidney Disease | Business Wire

- ↑ J Clin Invest. 2013;123(7):3084–3098. doi:10.1172/JCI64401 : http://m.jci.org/articles/view/64401

- ↑ Vitamin B3 holds promise for treating polycystic kidney disease, research suggests

- ↑ NYU Langone Medical Center

- ↑ Niacin and niacinamide (Vitamin B3): MedlinePlus Supplements

- ↑ PKD Clinic: Niacin and PKD - PKD Treatment

- ↑ How Much Niacin Per Day Should I Consume With PKD - Kidney Healthy Web

- ↑ 3 Ways To Stop Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD) | Healthy Lifestyle Wiki

- ↑ Polycystic Kidney Disease And Vitamin B3 (niacin)

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 JCI - Sirtuin 1 inhibition delays cyst formation in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease

- ↑ Vitamin B3 and Polycystic Kidney Disease - PKD Treatment

- ↑ Sirtuin 1 inhibition delays cyst format - PubMed Mobile

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 http://www.cell.com/trends/biochemical-sciences/abstract/S0968-0004(05)00194-5?cc=y?cc=y

- ↑ Naringenin inhibits the growth of Dictyosteli... [Br J Pharmacol. 2013] - PubMed - NCBI

- ↑ Could grapefruit be good for your kidneys? - ScienceDaily

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Citrus fruits may prevent kidney cysts - Medical News Today

Additional images

-

Adult polycystic kidney.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney. |

- Photo demonstrating size of polycystic kidneys

- http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/polycystic/index.htm

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/disease/PKD.html

- The Polycystic Kidney Disease Foundation website - more details on trials, treatments, nutrition, and support.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||