Automatic sequence

An automatic sequence (or k-automatic sequence) is an infinite sequence of terms characterized by a finite automaton. The n-th term of the sequence is a mapping of the final state of the automaton when its input is the digits of n in some fixed base k.[1][2] A k-automatic set is a set of non-negative integers for which the sequence of values of its characteristic function is an automatic sequence: that is, membership of n in the set can be determined by a finite state automaton on the digits of n in base k.[3][4]

An automaton reading the base k digits from the most significant is said to be direct reading, and from the least significant is reverse reading.[4] However the two directions lead to the same class of sequences.[5]

Every automatic sequence is a morphic word.[6]

Automaton point of view

Let k be a positive integer, and D = (E, φ, e) be a deterministic automaton where

also let A be a finite set, and π:E → A a projection towards A.

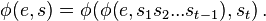

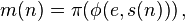

Extend the transition function φ from acting on single digits to acting on strings of digits by defining the action of φ on a string s consisting of digits s1s2...st as:

Define a function m from the set of positive integers to the set A as follows:

where s(n) is n written in base k. Then the sequence m = m(1)m(2)m(3)... is called a k-automatic sequence.[1]

Substitution point of view

Let σ be a k-uniform morphism of the free monoid E∗, so that  and which is prolongable[7] on

and which is prolongable[7] on  : that is, σ(e) begins with e. Let A and π be defined as above. Then if w is a fixpoint of σ, that is to say w = σ(w), then m = π(w) is a k-automatic sequence over A:[8] this is Cobham's theorem.[2] Conversely every k-automatic sequence is obtained in this way.[4]

: that is, σ(e) begins with e. Let A and π be defined as above. Then if w is a fixpoint of σ, that is to say w = σ(w), then m = π(w) is a k-automatic sequence over A:[8] this is Cobham's theorem.[2] Conversely every k-automatic sequence is obtained in this way.[4]

Decimation

Fix k > 1. For a sequence w we define the k-decimations of w for r=0,1,...,k-1 to be the subsequences consisting of the letters in positions congruent to r modulo k. The decimation kernel of w consists of the set of words obtained by all possible repeated decimations of w. A sequence is k-automatic if and only if the k-decimation kernel is finite.[9][10][11]

1-automatic sequences

k-automatic sequences are normally only defined for k ≥ 2.[1] The concept can be extended to k = 1 by defining a 1-automatic sequence to be a sequence whose n-th term depends on the unary notation for n, that is (1)n. Since a finite state automaton must eventually return to a previously visited state, all 1-automatic sequences are eventually periodic.

Properties

For given k and r, a set is k-automatic if and only if it is kr-automatic. Otherwise, for h and k multiplicatively independent, then a set is both h-automatic and k-automatic if and only if it is 1-automatic, that is, ultimately periodic.[12] This theorem is also due to Cobham,[13] with a multidimensional generalisation due to Semënov.[14][15]

If u(n) is a k-automatic sequence then the sequences u(kn) and u(kn−1) are ultimately periodic.[16] Conversely, if v(n) is ultimately periodic then the sequence u defined by u(kn) = v(n) and otherwise zero is k-automatic.[17]

Let u(n) be a k-automatic sequence over the alphabet A. If f is a uniform morphism from A∗ to B∗ then the word f(u) is k-automatic sequence over the alphabet B.[18]

Let u(n) be a sequence over the alphabet A and suppose that there is an injective function j from A to the finite field Fq. The associated formal power series is

The sequence u is q-automatic if and only if the power series fu is algebraic over the rational function field Fq(z).[19]

Examples

The following sequences are automatic:

- Thue-Morse sequence: take E = A = {0, 1}, e = 0, π = id, and σ such that σ(0) = 01, σ(1) = 10; we get the fixpoint 01101001100101101001011001101001..., which is in fact the Thue-Morse word. The n-th term is the parity of the base 2 representation of n and the sequence is thus 2-automatic.[1][2][20][21] The 2-kernel consists of the sequence itself and its complement.[22] The associated power series T(z) satisfies

- over the field F2(z).[23]

- Rudin–Shapiro sequence[20][24]

- Baum–Sweet sequence[25]

- Regular paperfolding sequence[21][26][27] and a general paperfolding sequence with a periodic sequence of folds[28]

- The period-doubling sequence, defined by the parity of the power of 2 dividing n; it is the fixed point of the morphism 0 → 01, 1 → 00.[29]

Automatic real number

An automatic real number is a real number for which the base-b expansion is an automatic sequence.[30][31] All such numbers are either rational or transcendental, but not a U-number.[32][33] Rational numbers are k-automatic in base b for all k and b.[31]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Allouche & Shallit (2003) p.152

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Berstel et al (2009) p.78

- ↑ Allouche & Shallit (2003) p.168

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Pytheas Fogg (2002) p.13

- ↑ Pytheas Fogg (2002) p.15

- ↑ Lothaire (2005) p.524

- ↑ Allouche & Shallit (2003) p.212

- ↑ Allouche & Shallit (2003) p.175

- ↑ Allouche & Shallitt (2003) p.185

- ↑ Lothaire (2005) p.527

- ↑ Berstel & Reutenauer (2011) p.91

- ↑ Allouche & Shallit (2003) pp.345-350

- ↑ Cobham, Alan (1969). "On the base-dependence of sets of numbers recognizable by finite automata". Math. Systems Theory 3 (2): 186–192. doi:10.1007/BF01746527.

- ↑ Semenov, A. L. (1977). "Presburgerness of predicates regular in two number systems". Sibirsk. Mat. Zh. (in Russian) 18: 403–418.

- ↑ Point, F.; Bruyère, V. (April 1997). "On the Cobham-Semenov theorem". Theory of Computing Systems 30 (2): 197–220. doi:10.1007/BF02679449.

- ↑ Lothaire (2005) p.529

- ↑ Berstel & Reutenauer (2011) p.103

- ↑ Lothaire (2005) p.532

- ↑ Berstel & Reutenauer (2011) p.93

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Lothaire (2005) p.525

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Berstel & Reutenauer (2011) p.92

- ↑ Lothaire (2005) p.528

- ↑ Berstel & Reutenauer (2011) p.94

- ↑ Allouche & Shallit (2003) p.154

- ↑ Allouche & Shallit (2003) p.156

- ↑ Allouche & Shallit (2003) p.155

- ↑ Lothaire (2005) p.526

- ↑ Allouche & Shallit (2003) p.183

- ↑ Allouche & Shallit (2003) p.176

- ↑ Shallitt (1999) p.556

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Allouche & Shallit (2003) p.379

- ↑ Adamczewski, Boris; Bugeaud, Yann (2007), "On the complexity of algebraic numbers. I. Expansions in integer bases", Annals of Mathematics 165 (2): 547–565, doi:10.4007/annals.2007.165.547, Zbl 1195.11094

- ↑ Bugeaud, Yann (2012), Distribution modulo one and Diophantine approximation, Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics 193, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 192–193, ISBN 978-0-521-11169-0, Zbl pre06066616

- Allouche, Jean-Paul; Shallit, Jeffrey (2003). Automatic Sequences: Theory, Applications, Generalizations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82332-6. Zbl 1086.11015.

- Berstel, Jean; Lauve, Aaron; Reutenauer, Christophe; Saliola, Franco V. (2009). Combinatorics on words. Christoffel words and repetitions in words. CRM Monograph Series 27. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-4480-9. Zbl 1161.68043.

- Berstel, Jean; Reutenauer, Christophe (2011). Noncommutative rational series with applications. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications 137. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19022-0. Zbl 1250.68007.

- Berthé, Valérie; Rigo, Michel, eds. (2010). Combinatorics, automata, and number theory. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications 135. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51597-9. Zbl 1197.68006.

- Shallit, Jeffrey (1999). "Number theory and formal languages". In Hejhal, Dennis A.; Friedman, Joel; Gutzwiller, Martin C.; Odlyzko, Andrew M.. Emerging applications of number theory. Based on the proceedings of the IMA summer program, Minneapolis, MN, USA, July 15--26, 1996. The IMA volumes in mathematics and its applications 109. Springer-Verlag. pp. 547–570. ISBN 0-387-98824-6.

- Lothaire, M. (2005). Applied combinatorics on words. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications 105. A collective work by Jean Berstel, Dominique Perrin, Maxime Crochemore, Eric Laporte, Mehryar Mohri, Nadia Pisanti, Marie-France Sagot, Gesine Reinert, Sophie Schbath, Michael Waterman, Philippe Jacquet, Wojciech Szpankowski, Dominique Poulalhon, Gilles Schaeffer, Roman Kolpakov, Gregory Koucherov, Jean-Paul Allouche and Valérie Berthé. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84802-4. Zbl 1133.68067.

- Loxton, J. H. (1988). "13. Automata and transcendence". In Baker, A.. New Advances in Transcendence Theory. Cambridge University Press. pp. 215–228. ISBN 0-521-33545-0. Zbl 0656.10032.

- Pytheas Fogg, N. (2002). Substitutions in dynamics, arithmetics and combinatorics. Lecture Notes in Mathematics 1794. Editors Berthé, Valérie; Ferenczi, Sébastien; Mauduit, Christian; Siegel, A. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-44141-7. Zbl 1014.11015.