Autogyro

| Autogyro | |

|---|---|

ELA 07S in flight. |

An autogyro (from Greek α’υτός + γύρος, self-turning), also known as gyroplane, gyrocopter, or rotaplane, is a type of rotorcraft which uses an unpowered rotor in autorotation to develop lift, and an engine-powered propeller, similar to that of a fixed-wing aircraft, to provide thrust. While similar to a helicopter rotor in appearance, the autogyro's rotor must have air flowing through the rotor disc to generate rotation. Invented by the Spanish engineer Juan de la Cierva to create an aircraft that could fly safely at slow speeds, the autogyro was first flown on 9 January 1923, at Cuatro Vientos Airfield in Madrid.[1] De la Cierva's aircraft resembled the fixed-wing aircraft of the day, with a front-mounted engine and propeller in a tractor configuration to pull the aircraft through the air. Under license from Cierva in the 1920s and 1930s, the Pitcairn & Kellett companies made further innovations.[2] Late-model autogyros patterned after Etienne Dormoy's Buhl A-1 Autogyro and Igor Bensen's designs feature a rear-mounted engine and propeller in a pusher configuration. The term Autogiro was a trademark of the Cierva Autogiro Company, and the term Gyrocopter was used by E. Burke Wilford who developed the Reiseler Kreiser feathering rotor equipped gyroplane in the first half of the twentieth century. The latter term was later adopted as a trademark by Bensen Aircraft.

Principle of operation

An autogyro is characterized by a free-spinning rotor that turns because of passage of air through the rotor from below.[3][4] The vertical (downward) component of the total aerodynamic reaction of the rotor gives lift for the vehicle, and sustains the autogyro in the air. A separate propeller provides forward thrust, and can be placed in a tractor configuration with the engine and propeller at the front of the fuselage (e.g., Cierva), or pusher configuration with the engine and propeller at the rear of the fuselage (e.g., Bensen).

Whereas a helicopter works by forcing the rotor blades through the air, drawing air from above, the autogyro rotor blade generates lift in the same way as a glider's wing by changing the angle of the air[3] as the air moves upwards and backwards relative to the rotor blade.[5] The free-spinning blades turn by autorotation; the rotor blades are angled so that they not only give lift,[6] but the angle of the blades causes the lift to accelerate the blades' rotation rate, until the rotor turns at a stable speed with the drag and thrust forces in balance.

|

| |

|

|

Because the craft must be moving forward (with respect to the surrounding air) in order to force air through the overhead rotor, autogyros are generally not capable of vertical takeoff or landing (unless in a strong headwind). A few types have shown short takeoff or landing.

Pitch control of the autogyro is by tilting the rotor fore and aft; roll control is by tilting the rotor laterally (side to side). Three designs to affect the tilt of the rotor are a tilting hub (Cierva), swashplate (Air & Space 18A), or servo-flaps. A rudder provides yaw control. On pusher configuration autogyros, the rudder is typically placed in the propeller slipstream to maximize yaw control at low airspeed (but not always, as seen in the McCulloch J-2, with twin rudders placed outboard of the propeller arc).

Flight controls

There are three primary flight controls: control stick, rudder pedals, and throttle. Typically, the control stick is termed cyclic and tilts the rotor in the desired direction to provide pitch and roll control (some autogyros do not tilt the rotor relative to the airframe, or only do so in one dimension, and have conventional control surfaces to vary the remaining degrees of freedom). The rudder pedals provide yaw control, and the throttle controls engine power.

Secondary flight controls include the rotor transmission clutch, also known as a pre-rotator, which when engaged drives the rotor to start it spinning before takeoff, and collective pitch to reduce blade pitch before driving the rotor. Collective pitch controls are not usually fitted to autogyros, but can be found on the Air & Space 18A and McCulloch J-2 and the Westermayr Tragschrauber and are capable of near VTOL performance. Unlike a helicopter, autogyros without collective pitch or another jump start facility need a runway to take off; however, they are capable of landing with a very short or zero ground roll. Like helicopters, each autogyro has a specific height–velocity diagram for safest operation, although the dangerous area is usually smaller than for helicopters.[7]

Rocket powered autogyro

So-called tipjets, actually hydrogen peroxide rockets, are placed at the tips of the rotor. The rockets are used only during takeoff and emergency landing, so they do not consume much propellant. The hydrogen peroxide rockets are light-weight, inexpensive, reliable, noisy, and transform the autogyro into an aircraft that has almost all the advantages of a helicopter (specifically vertical takeoffs and landings) at a fraction of the helicopter cost. Furthermore, the engine weight and engine power may be reduced by half because a smaller engine is needed for takeoff. The Fairey Jet Gyrodyne and Fairey Rotodyne had true tipjets instead of the rockets. They were technically successful but were not mass-produced due to concerns about tipjet noise.

Pusher vs tractor configuration

Modern autogyros typically follow one of two basic configurations. The most common design is the pusher configuration, where the engine and propeller are located behind the pilot and rotor mast, such as in the Bensen "Gyrocopter". It was developed by Igor Bensen in the decades following World War II, and came into widespread use shortly afterward.

Less common today is the tractor configuration. In this version the engine and propeller are located at the front of the aircraft, ahead of the pilot and rotor mast. This was the primary configuration in early autogyros, but became less common after the advent of the helicopter. It has enjoyed a revival since the mid-1970s.

History

Juan de la Cierva was a Spanish engineer and aeronautical enthusiast. In 1921, he participated in a design competition to develop a bomber for the Spanish military. De la Cierva designed a three-engined aircraft, but during an early test flight, the bomber stalled and crashed. De la Cierva was troubled by the stall phenomenon and vowed to develop an aircraft that could fly safely at low airspeeds. The result was the first successful rotorcraft, which he named Autogiro in 1923.[8] De la Cierva's autogyro used an airplane fuselage with a forward-mounted propeller and engine, a rotor mounted on a mast, and a horizontal and vertical stabilizer.

Early development

De la Cierva's first three designs (C.1, C.2, and C.3) were unstable because of aerodynamic and structural deficiencies in their rotors. His fourth design, the C.4, made the first documented flight of an autogyro on 17 January 1923, piloted by Alejandro Gomez Spencer at Cuatro Vientos airfield in Madrid, Spain (9 January according to Cierva).[4] De la Cierva had fitted the rotor of the C.4 with flapping hinges to attach each rotor blade to the hub. The flapping hinges allowed each rotor blade to flap, or move up and down, to compensate for dissymmetry of lift, the difference in lift produced between the right and left sides of the rotor as the autogyro moves forward.[8][9] Three days later, the engine failed shortly after takeoff and the aircraft descended slowly and steeply to a safe landing, validating De la Cierva's efforts to produce an aircraft that could be flown safely at low airspeeds.

De la Cierva developed his C.6 model with the assistance of Spain's Military Aviation establishment, having expended all his funds on development and construction of the first five prototypes. The C.6 first flew in February 1925, including a flight of 10.5 km (6.5 mi) from Cuatro Vientos airfield to Getafe airfield in about 8 minutes, a significant accomplishment for any rotorcraft of the time. Shortly after De la Cierva's success with the C.6, Cierva accepted an offer from Scottish industrialist James G. Weir to establish the Cierva Autogiro Company in England, following a demonstration of the C.6 before the British Air Ministry at RAE Farnborough, on 20 October 1925. Britain had become the world centre of autogyro development.

A crash in February 1927, caused by blade root failure, led to an improvement in rotor hub design. A drag hinge was added in conjunction with the flapping hinge to allow each blade to move fore and aft and relieve in-plane stresses, generated as a byproduct of the flapping motion. This development led to the Cierva C.8, which, on 18 September 1928, made the first rotorcraft crossing of the English Channel followed by a tour of Europe.

The U.S. industrialist Harold Frederick Pitcairn, upon learning of the successful flights of the autogyro, had previously visited De la Cierva in Spain. In 1928 he visited him again, in England, after taking a C.8 L.IV test flight piloted by Arthur H.C.A. Rawson. Being particularly impressed with the autogyro's safe vertical descent capability, Pitcairn purchased a C.8 L.IV with a Wright Whirlwind engine. Arriving in the United States on 11 December 1928 accompanied by Rawson, this autogyro was redesignated C.8W.[4] Subsequently, production of autogyros was licensed to a number of manufacturers, including the Pitcairn Autogiro Company in the U.S. and Focke-Wulf of Germany.

In 1927 Engelbert Zaschka, a pioneering German engineer, invented a combined helicopter and autogyro. The principal advantage of the Zaschka machine is in its ability to remain motionless in the air for any length of time and to descend in a vertical line, so that a landing may be accomplished on the flat roof of a large house. In appearance, the machine does not differ much from the ordinary monoplane, but the carrying wings revolve around the body.

Development of the autogyro continued in search for a means to accelerate the rotor prior to takeoff (called prerotating). Rotor drives initially took the form of a rope wrapped around the rotor axle and then pulled by a team of men to accelerate the rotor – this was followed by a long taxi to bring the rotor up to speed sufficient for takeoff. The next innovation was flaps on the tail to redirect the propeller slipstream into the rotor while on the ground. This design was first tested on a C.19 in 1929. Efforts in 1930 had shown that development of a light and efficient mechanical transmission was not a trivial undertaking. But in 1932, the Pitcairn-Cierva Autogiro Company of Willow Grove, Pennsylvania, United States, finally solved the problem with a transmission driven by the engine.

Buhl Aircraft Company produced its Buhl A-1, the first autogyro with propulsive rear motor, designed by Etienne Dormoy and meant for aerial observation (motor behind pilot and camera). It had its maiden flight on 15 December 1931.[10]

De la Cierva's early autogyros were fitted with fixed rotor hubs, small fixed wings, and control surfaces like those of a fixed-wing aircraft. At low airspeeds, the control surfaces became ineffective and could readily lead to loss of control, particularly during landing. In response, Cierva developed a direct control rotor hub, which could be tilted in any direction by the pilot. De la Cierva's direct control was first developed on the Cierva C.19 Mk. V and saw production on the Cierva C.30 series of 1934. In March 1934 this type of autogyro became the first rotorcraft to take off and land on the deck of a ship, when a C.30 performed trials on board the Spanish navy seaplane tender Dédalo off Valencia.[11]

Later that year, during the leftist Asturias' revolt in October, an autogyro made a reconnaissance flight for the loyal troops, marking the first military employment of a rotorcraft.[12]

When improvements in helicopters made them practical, autogyros became largely neglected. Also, they were susceptible to ground resonance.[9] They were, however, used in the 1930s by major newspapers, and by the United States Postal Service for mail service between the Camden, New Jersey airport and the top of the post office building in downtown Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[13]

World War II

The Avro Rota autogyro was used by the Royal Air Force to calibrate the coastal radar stations during and after the Battle of Britain.[14]

In World War II, Germany pioneered a very small gyroglider rotor kite, the Focke-Achgelis Fa 330 "Bachstelze" (Water-wagtail), towed by U-boats to provide aerial surveillance.

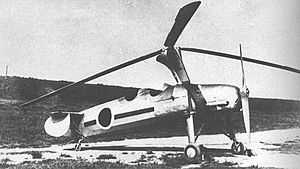

The Imperial Japanese Army developed the Kayaba Ka-1 Autogyro for reconnaissance, artillery-spotting, and anti-submarine uses. The Ka-1 was based on the Kellett KD-1 first imported to Japan in 1938. The craft was initially developed for use as an observation platform and for artillery spotting duties. The Army liked the craft's short take-off span, and especially its low maintenance requirements. In 1941 production began, with the machines assigned to artillery units for spotting the fall of shells. These carried two crewmen: a pilot and a spotter.

Later, the Japanese Army commissioned two small aircraft carriers intended for coastal antisubmarine (ASW) duties. The spotter's position on the Ka-1 was modified to carry one small depth charge. Ka-1 ASW autogyros operated from shore bases as well as the two small carriers. They appear to have been responsible for at least one submarine sinking.

Postwar developments

The autogyro was resurrected after World War II when Dr. Igor Bensen, a Russian immigrant in the USA, saw a captured German U-Boat's Fa 330 gyroglider and was fascinated by its characteristics. At work he was tasked with the analysis of the British military "Rotachute" gyro glider designed by expatriate Austrian Raoul Hafner. This led him to adapt the design for his own purposes and eventually market the B-7. Bensen submitted an improved version, the Bensen B-8M, for testing to the United States Air Force, which designated it the X-25.[15] The B-8M was designed to use surplus McCulloch engines used on flying unmanned target drones.

Ken Wallis developed a miniature autogyro craft, the Wallis autogyro, in England in the 1960s, and autogyros built similar to Wallis' design appeared for a number of years. Ken Wallis' designs have been used in various scenarios including military training, police reconnaissance, and in another case a search for the Loch Ness Monster.

Three different autogyro designs have been certified by the Federal Aviation Administration for commercial production: the Umbaugh U-18/Air & Space 18A of 1965, the Avian 2-180 Gyroplane of 1967, and the McCulloch J-2 of 1972. All have been commercial failures, for various reasons.

Bensen Gyrocopter

The basic Bensen Gyrocopter design is a simple frame of square aluminium or galvanized steel tubing, reinforced with triangles of lighter tubing. It is arranged so that the stress falls on the tubes, or special fittings, not the bolts. A front-to-back keel mounts a steerable nosewheel, seat, engine, and a vertical stabilizer. Outlying mainwheels are mounted on an axle. Some versions may mount seaplane-style floats for water operations.

Bensen-type autogyros use a pusher configuration for simplicity and to increase visibility for the pilot. Power can be supplied by a variety of engines. McCulloch drone engines, Rotax marine engines, Subaru automobile engines, and other designs have been used in Bensen-type designs.

The rotor is mounted atop the vertical mast. The rotor system of all Bensen-type autogyros is of a two-blade teetering design. There are some disadvantages associated with this rotor design, but the simplicity of the rotor design lends itself to ease of assembly and maintenance and is one of the reasons for its popularity. Aircraft-quality birch was specified in early Bensen designs, and a wood/steel composite is used in the world speed record holding Wallis design. Gyroplane rotor blades are made from other materials such as aluminium and GRP-based composite blades.

Because of Bensen's pioneering of the concept and the popularity of his design, "Gyrocopter" has become a generic term for pusher configuration autogyros.

The success of Bensen triggered a number of other designs, some of them fatally flawed with an offset between the centre of gravity and thrust line, risking a Power Push-Over (PPO or bunt-over) causing death to the pilot and giving gyroplanes in general a poor reputation – in contrast to Cierva's original intention and early statistics. Most new autogyros are now safe from PPO.[16]

21st century development and use

In 2002, Groen Brothers Aviation's Hawk 4 provided perimeter patrol for the Winter Olympics and Paralympics in Salt Lake City, Utah. The aircraft completed 67 missions and accumulated 75 hours of maintenance-free flight time during its 90-day operational contract.[17]

Over 1,000 autogyros worldwide are used by authorities for military and law enforcement, but the first US Police authorities to evaluate an autogyro are the Tomball, Texas, police, on a $40,000[18] grant from DoJ together with city funds,[19] costing much less than a helicopter to buy ($75,000) and operate ($50/hour).[20][21] Although it is able to land in 40-knot crosswinds,[22] a minor accident happened when the rotor was not kept under control in a wind gust.[23]

Since 2009 several projects in Kurdistan, Iraq have been realized. In 2010 the first autogyro was handed over to the Kurdish Minister of Interiors, Mr. Karim Sinjari. Targets of the projects are the training of pilots which should control and monitor for the interior ministry the approach and takeoff paths of the airports in Erbil, Sulaymaniyah, and Dohuk to prevent terroristic encroachments. The gyroplane pilots also form the backbone of the pilot crew of the Kurdish police which are trained to pilot on Eurocopter EC 120 B helicopters.[24][25][26]

From 2009 to 2010 for the first time a world tour was undertaken by autogyro. The German pilot couple Melanie and Andreas Stütz flew in 18 months in different gyroplane types in Europe, southern Africa, Australia, New Zealand, USA and South America. The adventure was documented in the book "WELTFLUG – The Gyroplane Dream" and in the film "Weltflug.tv - The Gyrocopter World Tour".[27]

Certification by national aviation authorities

UK certification

Some autogyros, such as the Rotorsport MT03,[28] MTO Sport (open tandem), & Calidus (enclosed tandem), and the Magni Gyro M16C (open tandem)[29] & M24 (enclosed side by side) have type approval by the United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) under British Civil Airworthiness Requirements CAP643 Section T.[30] Others operate under a permit to fly issued by the Popular Flying Association similar to the US experimental aircraft certification. However, the CAA's assertion that autogyros have a poor safety record means that a permit to fly will be granted only to existing types of autogyro. All new types of autogyro must be submitted for full type approval under CAP643 Section T.[31] Beginning in 2014, the CAA allows gyro flight over congested areas.[32]

In 2005, the CAA issued a mandatory permit directive (MPD) which restricted operations for single-seat autogryos, and were subsequently integrated into CAP643 Issue 3 published on 12 August 2005.[30] The restrictions are concerned with the offset between the centre of gravity and thrust line, and apply to all aircraft unless evidence is presented to the CAA that the CG/Thrust Line offset is less than 2 inches (5 cm) in either direction. The restrictions are summarised as follows:

- Aircraft with a cockpit/nacelle may be operated only by pilots with more than 50 hours solo flight experience following the issue of their licence.

- Open-frame aircraft are restricted to a minimum speed of 30 mph (26 knots), except in the flare.

- All aircraft are restricted to a Vne (maximum airspeed) of 70 mph (61 knots)

- Flight is not permitted when surface winds exceed 17 mph (15 knots) or if the gust spread exceeds 12 mph (10 knots)

- Flight is not permitted in moderate, severe or extreme turbulence and airspeed must be reduced to 63 mph (55 knots) if turbulence is encountered mid-flight.

These restrictions do not apply to autogyros with type approval under CAA CAP643 Section T, which are subject to the operating limits specified in the type approval.

United States certification

A certificated autogyro must meet mandated stability and control criteria; in the United States these are set forth in Federal Aviation Regulations Part 27: Airworthiness Standards: Normal Category Rotorcraft.[33] The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration issues a Standard Airworthiness Certificate to qualified autogyros. Amateur-built or kit-built aircraft are operated under a Special Airworthiness Certificate in the Experimental category.[34] Per FAR 1.1, the FAA uses the term "gyroplane" for all autogyros, regardless of the type of Airworthiness Certificate. They are considered airplanes and must abide by all no fly zones in US airspace

World records

In 1931, Amelia Earhart (USA) flew a Pitcairn PCA-2 to a women's world altitude record of 18,415 ft (5,613 m).[35]

Wing Commander Ken Wallis (UK) held most of the autogyro world records during his autogyro flying career. These include a time-to-climb,[36] a speed record of 189 km/h (111.7 mph),[37] and the straight-line distance record of 869.23 km (540.11 mi). On 16 November 2002, at 89 years of age, Wallis increased the speed record to 207.7 km/h (129.1 mph)[38] – and simultaneously set another world record as the oldest pilot to set a world record.

The autogyro is one of the last remaining types of aircraft which has not yet been used to circumnavigate the globe. Expedition Global Eagle was the first attempt in history to circumnavigate the globe using an autogyro.[39] The expedition set the record for the longest flight over water by an autogyro during the segment from Muscat, Oman, to Karachi.[40] The attempt was finally abandoned because of bad weather after a trip totalling 7,500 miles (12,100 km).

As of 2014, Andrew Keech (USA) holds several records. He made a transcontinental flight in his self-built Little Wing Autogyro "Woodstock" from Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, to San Diego, California, in October 2003 and set three world records for speed over a recognized course.[41] The three records were verified by tower personnel or by official observers of the United States' National Aeronautic Association (NAA). On 9 February 2006 he broke two of his world records and set a record for distance, ratified by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI): Speed over a closed circuit of 500 km (311 mi) without payload: 168.29 km/h (104.57 mph),[42] speed over a closed circuit of 1,000 km (621 mi) without payload: 165.07 km/h (102.57 mph),[43] and distance over a closed circuit without landing: 1,019.09 km (633.23 mi).[44][45]

| Year | Pilot | Record type | Record | Aircraft | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Ken Wallis (UK) | Speed over a 3 km course | 207.7 km/h[38] | Wallis Type WA-121/Mc (GBAHH) | Oldest pilot to set record |

| 1998 | Ken Wallis (UK) | Time to climb, 3000m | 7mn 20s[36] | Wallis Type WA-121/Mc (G-BAHH) | |

| 2004 | Andrew Keech (USA) | Altitude without payload | 8049 m[46] | Little Wing LW-5 (N100MK) | Web |

| 2007 | Andrew Keech (USA) | Distance without landing | 1414.64 km[47] | Little Wing LW-5 (N100MK) |

Norman Surplus (UK) from Larne in Northern Ireland, became the second person to attempt a world circumnavigation by Autogyro aircraft on 22 March 2010. Flying a Rotorsport UK MT-03 Autogyro, registered G-YROX, the Gyrox Goes Global expedition commenced from a local sports field in the pilot's home town. Special arrangements for time keeping were made so that the Official FAI world record attempt could commence from this unusual starting point, as no conventional airfield had been established in the Larne area at this time. By 30 April 2010, G-YROX and pilot had flown (solo and without autopilot) through England, France, Italy, Greece, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, UEA, Oman, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and Myanmar to reach Thailand. On passing through Jamshedpur, India, Norman had surpassed the previous longest distance ever flown by an Autogyro, set by Barry Jones in 2004. On 1 May 2010 G-YROX suffered damage during a forced ditching event in a shallow lake alongside Nong Prue Airfield in Thailand. The flight was considerably delayed while permission to repair the UK-registered aircraft in Thailand was sought. This process lasted nine weeks, and the subsequent repair of the aircraft took a further three weeks. The circumnavigation flight was recommenced on 1 August 2010 and quick progress was made through Thailand, West Malaysia, East Malaysia and the Philippines. The flight was once more delayed in mid-August 2010 with initial permission difficulties for entry in Japan. By early September 2010, with the prospect of the Bering Sea crossing corridor soon closing for the long Arctic winter ahead, the decision was made to overwinter the aircraft in the Philippines at Woodlands Airpark, Luzon Island. In mid-May 2011 the flight was recommenced but a further nine weeks of permission delays for Japan ensued. The flight finally got under way again in mid-July 2011 and flew into Japan via Okinawa Island. Again quick progress was made, with the aircraft arriving in late July 2011 at Shonai Airport, Yamagata prefecture, NW Japan. Further permission difficulties for entry into the Russian Far East effectively grounded the aircraft since August 2011. Given the ongoing refusal from the Russian government, the onward circumnavigation flight to the Bering Sea was cancelled and the G-YROX was transported in shipping container to the US in December 2014 where it is passing the winter . En-route between Northern Ireland and Japan, Norman Surplus has established nine FAI world records for Autogyro flight.[48]

Autogyros in fiction

An indication of the pre-World War II popularity of the autogyro, its subsequent decline and later rise of interest can be inferred from its appearances in fiction of the day. Appearances include:

- In the film International House (1933), W. C. Fields's character flies around the globe in his autogyro The Spirit of Brooklyn.

- In the film It Happened One Night (1934), the bridegroom King Westley arrives dramatically for the wedding, piloting the Kellett K-3 Autogiro NC12691.[49]

- An autogyro briefly appears in Alfred Hitchcock's movie The 39 Steps (1935).

- Batman's first aircraft was an autogyro. The "Batgyro" was introduced in Detective Comics #31 in September 1939. It only made three appearances before being replaced by a more conventional fixed-wing aircraft.

- In the classic science fiction film of H.G. Wells' Things to Come (1936), the heroes of the story arrive dramatically at the Space Gun in an Art Deco-style autogyro (at 83m), to mitigate the destruction of the Space Gun by extremists. The autogyro in the film was designed by celebrated art deco designer Norman Bel Geddes, who assisted production designer William Cameron Menzies on the look of the world of tomorrow.

- Fictional characters Doc Savage[50] and The Shadow featured autogyros in their 1930s and 1940s pulp magazine adventures, as did Tom Strong in his pulp styled comic.[51]

- Little Nellie, the autogyro featured in the 1967 James Bond film You Only Live Twice, was a Ken Wallis WA-116 design and was piloted by Wallis in its film scenes. In the film it was shipped by Q in four suitcases and assembled before use.[52][53]

- A Wallis WA-116T two-seat autogyro is flown by character Ben Driscoll in an episode of the 1979 USA NBC-TV television science-fiction miniseries The Martian Chronicles. Driscoll flies the aircraft for "fifteen hundred miles" just to meet Genevieve Seltzer, whom he believes to be the last woman on Mars.[54][55]

- In the 1974 Doctor Who story, Planet of the Spiders, the Doctor uses a Campbell Cricket autogyro (G-AXVK) as part of a chase sequence.[56][57]

- In Hayao Miyazaki's 1979 anime film, The Castle of Cagliostro, Count Cagliostro utilizes an autogyro, notably against Lupin and company when they attempt to escape his castle residence with Clarisse in tow.

- An autogyro was heavily featured in the second Mad Max film, released in 1981, appearing in several scenes with its pilot, the Gyro Captain, as a major character. The pilot used in the flying sequences was Gerry Goodwin, doubling for the actor, Bruce Spence.[58]

- An autogyro appeared in the 1983 G.I. Joe toyline and 80's cartoons as the Cobra F.A.N.G.(Fully Armed Negator Gyrocopter).

- In the 1991 film, The Rocketeer, the hero Cliff Secord and his girlfriend Jenny are rescued from an exploding zeppelin at the last second by an autogyro piloted by their friend Peevy and a fictional Howard Hughes.

- The 2004 film Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events depicted a play put on by the acting troupe of the villain, Count Olaf, in which a prop autogyro was used for the Count's dramatic entrance.

See also

- CarterCopter / Carter PAV

- Fairey Rotodyne

- Groen Brothers Aviation

- Gyrodyne

- Rotor kite

- Helicopter

- List of autogyro models

- Piasecki Aircraft Corporation

- Rotary-wing hang glider

References

- ↑ Vector Flight

- ↑ Pitcairn-Cierva PCA-1A, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Bensen, Igor. "How they fly - Bensen explains all" Gyrocopters UK. Accessed: 10 April 2014. Quote: "air.. (is) deflected downward"

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Charnov, Bruce H. Cierva, Pitcairn and the Legacy of Rotary-Wing Flight Hofstra University. Accessed: 22 November 2011.

- ↑ http://www.phenix.aero/PHE-1210.html Gyrocopter vs. Helicopter

- ↑ "Autorotation", Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House, Inc. 17 April 2007 http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Autorotation

- ↑ Greg Gremminger. "HEIGHT VELOCITY CURVE for GYROPLANES" Magni Gyro. Accessed: December 2013.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Juan De La Cierva" Centennial of Flight Commission, 2003. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "The Contributions of the Autogyro." Centennial of Flight Commission, 2003. Retrieved: 28 January 2011.

- ↑ Buhl Aircraft Company site=www.rcgroups.com Buhl A-1 autogyro - 1931 and The Buhl A-1 Autogiro

- ↑ "The first Dedalo was an aircraft transportation ship and the first in the world from which an autogyro took off and landed." Naval Ship Systems Command, US: Naval Ship Systems Command technical news.1966, v. 15–16, page 40

- ↑ Payne, Stanley G. (1993). Spain's first democracy: the Second Republic, 1931–1936. Univ of Wisconsin Press, p. 219. ISBN 0-299-13674-4

- ↑ Pulle, Matt (5 July 2007). "Blade Runner". Dallas Observer. Vol. 27 (Issue 27) (Dallas, Tx). pp. 19–27.

- ↑ Burns, R.W. (1988). Radar Development to 1945. IEE. p. 139. ISBN 0-86341-139-8.

- ↑ Jenkins et al. AMERICAN X-VEHICLES, X-25 NASA, June 2003. Accessed: 18 February 2012.

- ↑ O'Conner, Timothy.This is not your father's gyroplane, Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA). Accessed: 12 February 2011.

- ↑ "Olympic Security Aided by Groen Brother's Hawk", Aero-News Network

- ↑ Supgul, Alexander. Tomball Police Equipped with Gyroplane 22 March 2011. Accessed 13 September 2011.

- ↑ Hauck, Robert S. Broadening horizons AirBeat Magazine July/August 2011. Accessed September 13, 2011. Video

- ↑ ALEA 2011: Autogyro debuts in the sky over Texas 22 July 2011. Accessed September 13, 2011.

- ↑ Hardigree, Matt. Flying the Police Aircraft of the Future, Wired (magazine) Video September 13, 2011. Accessed September 13, 2011.

- ↑ Desmon Butts Houston Chronicle

- ↑ "CEN14TA116" "Probable Cause" NTSB, April 23, 2014. Accessed: May 16, 2014.

- ↑ Iraq Defence & Security Summit 2012, The Aussie Aviator, 4 April 2012, Retrieved on 4 June 2012

- ↑ Kurdistan's traffic police to have helicopters, AKNews, 17 December 2011, Retrieved on 4 June 2012

- ↑ 5 Traffic Helicopters Arrive in Kurdistan, Iraq Business News, 28 February 2012, Retrieved on 4 June 2012

- ↑ Weltflug - The Gyrocopter World Tour

- ↑ "Type: RotorSport UK MT-03" (PDF). Gyroplane type approval data sheet (TADS). United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-02. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- ↑ "Magni M16C Type Approval Data Sheet (TADS)" (PDF). UK Civil Aviation Authority. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "CAP 643 British Civil Airworthiness Requirements Section T Light Gyroplanes" (PDF). United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- ↑ "CAP 733 Permit to Fly Aircraft" (PDF). United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority. p. 20, Chapter 3, Section 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- ↑ Van Wagenen, Juliet. "CAA Removes Overflight Restrictions on Gyroplanes" Aviation Today, 31 October 2014. Accessed: 17 November 2014.

- ↑ "Current FAR by Part". Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- ↑ "Experimental Category Operating Amateur-built, Kit-built, or Light-sport Aircraft". Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- ↑ "Achievements". Official Amelia Earhart website. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "FAI Record ID #5346 - Autogyro, Time to climb to a height of 3 000 m" Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Retrieved: 28 November 2013.

- ↑ "FAI Record ID #303 - Autogyro, Speed over a straight 15/25 km course" Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Retrieved: 28 November 2013.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "FAI Record ID #7601 - Autogyro, Speed over a 3 km course" Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Retrieved: 28 November 2013.

- ↑ BBC News You only live twice? A Nottingham man is part of a team hoping to circumnavigate the globe in one of James Bond's gadgets. Quote: "The autogyro is the only aircraft never to circumnavigate the globe. But now a team of soldiers are bidding to do just that and make a piece of aviation history."

- ↑ The Yorkshire Post The Eagle has landed – but pilot vows to try again Quote: "509-mile flight from Muscat to Karachi, the longest over water by an autogyro" 22 October 2004

- ↑ "Class E (Rotorcraft) record claims ratified". Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. 26 February 2004. Retrieved 12 September 2014. 1 2 1+2

- ↑ "FAI Record ID #13113 - Speed over a closed circuit of 500 km without payload" Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Retrieved: 12 September 2014.

- ↑ "FAI Record ID #13115 - Speed over a closed circuit of 1000 km without payload" Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Retrieved: 12 September 2014.

- ↑ "FAI Record ID #13111 - Speed over a closed circuit without landing" Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Retrieved: 12 September 2014.

- ↑ "History of Records: Andrew C. KEECH (USA)". Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ "FAI Record ID #9597 - Autogyro, altitude" Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Retrieved: 28 November 2013.

- ↑ "FAI Record ID #14695 - Autogyro, distance without landing" Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Retrieved: 28 November 2013.

- ↑ Norman Surplus (GYROX) list on FAI: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

- ↑ The KELLETT K-3 AUTOGIRO NC12691 Page of the Davis-Monthan Airfield Register Website

- ↑ "Doc piloting his gyro". Art Nocturne. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ↑ "Tom Strong and his Phantom Autogyro". America's Best Comics. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ↑ "Trivia: You Only Live Twice". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ↑ "K.H. Wallis". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ↑ "Wing Commander K. H. Wallis". Norfolk & Norwich Group of Advanced Motorists. Archived from the original on 14 March 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2009.

- ↑ "Kenneth Wallis". gyroplanpassion.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2009.

- ↑ "Ady Godwin Car Repairs (formerly Campbell Aircraft Ltd)". doctorwholoactions.net. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

- ↑ "Doctor Who – Top Gear". youtube.com. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

- ↑ "Gerry Goodwin". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- Rotorcraft Flying Handbook, FAA Manual H-8083-21, Chapters 15–22. Washington, DC: Flight Standards Service, Federal Aviation Administration, U.S. Dept. of Transportation, 2001. ISBN 1-56027-404-2.

- WELTFLUG - The Gyroplane Dream, 2013. ISBN 978-1493760947.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Autogyros. |

- "Development of the Autogiro : A Technical Perspective" : J. Gordon Leishman: Hofstra University, New York, 2003.

- Jeff Lewis' in-depth history of the Autogyro

- Popular Rotorcraft Association (United States)

- "Will Autogiro Banish Present Plane?", March 1931, pg 28

- "Feathering Of Blades Increase Gyro's Speed", April 1932, Popular Mechanics

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||