Australian feral camel

| Australian Feral Camel | |

|---|---|

| |

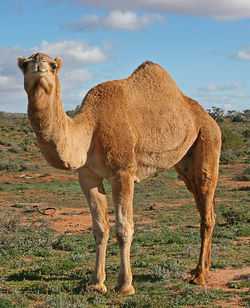

| Dromedary, Camelus dromedarius, the dominant species of the Australian feral camel | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Camelidae |

| Genus: | Camelus |

| Species: | Camelus dromedarius, Camelus bactrianus |

| Binomial name | |

| Camelus dromedarius, Camelus bactrianus Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Australian feral camels are feral populations of two species of camel; mostly dromedaries (Camelus dromedarius) but also some bactrian camels (Camelus bactrianus). Imported into Australia from Arabia, India and Afghanistan[1] during the 19th century for transport and construction during the colonisation of the central and western parts of Australia, many were released into the wild after motorised transport replaced the camels' role in the early 20th, forming a fast-growing feral population.

By 2008, it was feared that this population numbered about one million, and was projected to double every 8–10 years. Serious degradation of the local environment also threatened native species. A culling program was introduced in response, and by 2013 the feral population was estimated to have been reduced to around 300,000.

History

The first 24 camels were imported in 1860 for the Burke and Wills expedition. At least 15,000 camels with their handlers came to Australia between 1870 and 1900, primarily for transport use across the centre of the arid continent.[2] Most of these camels were dromedaries, especially from India, including the Bikaneri war camel from Rajasthan as a riding camel and lowland Indian camels for heavy work. Other dromedaries included the Bishari riding camel of North Africa and Arabia. Camels from the other main camel species, bactrians, were introduced from China and Mongolia.[3]

The first camel

The first suggestion of bringing camels to Australia was made in 1822 by Conrad Malte-Brun, whose Universal Geography contains the following;

For such an expedition, men of science and courage ought to be selected. They ought to be provided with all sorts of implements and stores, and with different animals, from the powers and instincts of which they may derive assistance. They should have oxen from Buenos Aires, or from the English settlements, mules from Senegal, and dromedaries from Africa or Arabia. The oxen would traverse the woods and the thickets; the mules would walk securely among rugged rocks and hilly countries; the dromedaries would cross the sandy deserts. Thus the expedition would be prepared for any kind of territory that the interior might present. Dogs also should be taken to raise game, and to discover springs of water; and it has even been proposed to take pigs, for the sake of finding out esculent roots in the soil. When no kangaroos and game are to be found the party would subsist on the flesh of their own flocks. They should be provided with a balloon for spying at a distance any serious obstacle to their progress in particular directions, and for extending the range of observations which the eye would take of such level lands as are too wide to allow any heights beyond them to come within the compass of their view.[4]

Decline in use and rise as a pest

After their use was finally superseded by modern transport by around 1930, some cameleers released their camels into the wild. These camels became the source for the large population of feral camels still existing today. Australia is the only country with feral herds of camels, and has the largest population of feral camels and the only herd of dromedary (one-humped) camels exhibiting wild behaviour in the world. (Other feral dromedary populations existed in the 20th century in Doñana National Park in Spain, and in the southwestern United States, while a small population of wild Bactrian camels still exists in the Gobi Desert.) Live camels are exported to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Brunei and Malaysia, where disease-free wild camels are prized as a delicacy. Australia's camels are also exported as breeding stock for Arab camel racing stables and for use in tourist venues in places such as the United States.[5]

In 2008 the number of feral camels was estimated to be more than one million, with the capability of doubling in number every 8–10 years.[6][7] The Australian Feral Camel Management Project, established in 2009, succeeded in culling over 160,000 camels, and by 2013 the feral population estimate was reduced to around 300,000.[8] Exports to Saudi Arabia where camel meat is consumed began in 2002.[9]

Impact on the environment

Although their impact on the environment is not as severe as some other pests introduced in Australia, camels ingest more than 80% of the plant species available. Degradation of the environment occurs when densities exceed two animals per km2, which is presently the case throughout much of their range in the Northern Territory where they are confined to two main regions: the Simpson Desert and the western desert area of the Central Ranges, Great Sandy Desert and Tanami Desert. Some traditional food plants harvested by Aboriginal people in these areas are seriously affected by camel-browsing. While having soft-padded feet makes soil erosion less likely, they do destabilise dune crests, which can contribute to erosion. Feral camels do have a noticeable impact on salt lake ecosystems, and have been found to foul waterholes.[7]

Effect on infrastructure

The effects on built infrastructure may be severe, as camels may sometimes destroy taps, pumps and even toilets as a means to obtain water, particularly in times of severe drought. They also damage stock fences and cattle watering points. These effects are felt particularly in Aboriginal and other remote communities where the costs of repairs are prohibitive.

Drought conditions in Australia during the first decade of the 21st century (the "Millennium drought") were particularly harsh, leading to thousands of camels dying of thirst in the Outback.[10] The problem of invading camels searching for water became great enough for the Australian authorities to plan to eradicate as many as 6,000 camels that had become a nuisance in the community of Docker River,[11] where the camels were causing severe damage in their search for food and water.[12] The planned cull was reported internationally and drew a strong reaction.[13][14]

See also

- Camel train

- Camel meat

References

- ↑ <http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-22522695>

- ↑ australia.gov.au > About Australia > Australian Stories > Afghan cameleers in Australia Accessed 8 May 2014.

- ↑ "Camel fact sheet". DSEWPaC. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-08-06. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- ↑ Conrad Malte-Brun, Universal Geography: Containing the description of India and Oceanica, Volume III 'containing the description of India and Oceanica', Book LVI 'Oceanica', Part IV 'New Holland and its dependancies', p.568. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, London 1822.

- ↑ From Australian outback to Saudi tables | csmonitor.com

- ↑ Managing the impacts of feral camels in Australia: a new way of doing business. Desert Knowledge CRC Report Number 47. Accessed 8 May 2014.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Northern Territory > Department of Land Resource Management > Feral Camel Accessed 8 May 2014.

- ↑ Ninti One > Managing the impacts of feral camels across remote Australia: Overview of the Australian Feral Camel Management Project Accessed 8 May 2014.

- ↑ "Australia supplies Saudis with camels". BBC News (British Broadcasting Corporation). 11 June 2002. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ Thousands of rotting camels polluting Australia's Outback News.com.au, 3 December 2009. Accessed 8 May 2014.

- ↑ Town lives in fear of marauding camels The Australian, 25 November 2009. Accessed 8 May 2014.

- ↑ "Australia Plans To Kill Thirsty Camels". CBS News. Associated Press. 26 November 2009. Archived from the original on 27 November 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ↑ Camel-lovers boycott 'Third World' Australia news.com.au, 2 December 2009. Accessed 8 May 2014.

- ↑ Camel-loving Saudis respond to cull The Australian, 21 January 2010. Accessed 8 May 2014.

External links

- Distribution and abundance of the feral camel (Camelus dromedarius) in Australia

- Camels Down Under, archived. Arthur Clark. pages 16–23 of the January/February 1988 print edition of Saudi Aramco World.

- National Feral Camel Action Plan

- Camels Australia Export Camel Industry Association website.

| ||||||||||||||