Attributable risk

In epidemiology, attributable risk is the difference in rate of a condition between an exposed population and an unexposed population.[1] Attributable risk is mostly calculated in cohort studies, where individuals are assembled on exposure status and followed over a period of time. Investigators count the occurrence of the diseases. The cohort is then subdivided by the level of exposure and the frequency of disease is compared between subgroups. One is considered exposed and another unexposed. The formula commonly used in Epidemiology books for Attributable risk is Ie - Iu = AR, where Ie = Incidence in exposed and Iu = incidence in unexposed. Once the AR is calculated, then the AR percent can be determined. The formula for that is 100*(Ie - Iu)/Ie .

Note: Ie is calculated by simply dividing the number of exposed people who get the disease by the total number who are exposed (N-exposeddis / N-exposedtot = Ie). Similarly, the Iu is calculated by dividing the number of unexposed people who get the disease by the total number who are not exposed (N-unexposeddis / N-unexposedtot = Iu).

The concept was first proposed by Levin in 1953.[2][3]

Diversity of interpretation

There is some variation in how the term is used.

The term population attributable risk (PAR) has been described as the reduction in incidence that would be observed if the population were entirely unexposed, compared with its current (actual) exposure pattern.[4] In this context, the comparison is to the existing pattern of exposure, not the absence of exposure.

There is some ambiguity in terminology. Population attributable risk is often simply called "attributable risk" (AR), and the latter term is most often associated with the above PAR definition. However, some epidemiologists use "attributable risk" when referring to the excess risk, also called the risk difference or rate difference.

Greenland and Robins distinguished between excess fraction and etiologic fraction in 1988.[5]

- Etiologic fraction is the proportion of the cases that the exposure had played a causal role in its development.

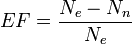

- It is defined as:[6]

- where:

- EF = Etiologic fraction

- Ne = Number of exposed individuals in a population that develop the disease

- Nn = Number of unexposed individuals in the same population that develop the disease.

- Excess fraction, however, is the proportion of the cases that occurs among exposed population that is in excess in comparison with the unexposed.

All etiologic cases are excess cases, but not vice versa. From the standpoint of both law and biology it is important to measure the etiology fraction. In most epidemiological studies, PAR measures only the excess fraction. (Larger than etiologic fraction)

Uses

Another measure, known as the population attributable fraction (PAF), can be calculated to help guide policymakers in planning public health interventions.[7] In practical terms, the population attributable fraction provides an indication of what the percentage reduction in the incidence rate of a disease could be in a given population if the exposure were eliminated altogether.[8] As a hypothetical example, if all radon exposure in a community were removed, and everything else were left unchanged, the number of lung cancer cases would decrease. The population attributable fraction provides an indication of the relative reduction in new cases of the disease in the event that this could be done. In other words, it indicates the proportion of new cases of a disease within a population that can be said to be due to (i.e. attributable to) a particular exposure.[9]

Combined PAR

The PAR for a combination of risk factors is the proportion of the disease that can be attributed to any of the risk factors studied. The combined PAR is usually lower than the sum of individual PARs since a diseased case can simultaneously be attributed to more than one risk factor and so be counted twice.

Assuming a multuplicative model with no interaction (i.e. no departure from multiplicative scale), combined PAR can be manually calculated by this formula:

References

- ↑ "Epidemiology for the uninitiated: 3. Comparing disease rates". Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- ↑ Paik, Myunghee Cho; Fleiss, Joseph L.; Levin, Bruce R. (2003). Statistical methods for rates and proportions. Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley-Interscience. p. 151. ISBN 0-471-52629-0.

- ↑ Levin ML (1953). "The occurrence of lung cancer in man". Acta Unio Int Contra Cancrum 9 (3): 531–41. PMID 13124110.

- ↑ Rothman K; Greenland S (1998). Modern Epidemiology, 2nd Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ Greenland S; Robins JM. (1988). "Conceptual problems in the definition and interpretation of attributable fractions.". Am J Epidemiol. 128 (6): 1185–1197. PMID 3057878.

- ↑ Page 43 in: Case control studies: design, conduct, analysis By James J. Schlesselman, Paul D. Stolley Edition: illustrated Published by Oxford University Press US, 1982 ISBN 0-19-502933-X, 9780195029338 354 pages

- ↑ Northridge ME. (1995). "public health methods: attributable risk as a link between causality and public health action.". Am J Public Health 85 (9): 1202–1203. doi:10.2105/AJPH.85.9.1202. PMC 1615585. PMID 7661224.

- ↑ Porta, Miquel S, ed. (2014). A Dictionary of Epidemiology. Oxford University Press. pp. 12–13; 187. ISBN 978-0-19-997673-7.

- ↑ Gefeller, Olaf (1992). "An Annotated Bibliography on the Attributable Risk". Biometrical Journal 34 (8): 1007–1012. doi:10.1002/bimj.4710340815.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||