Atlanta in the American Civil War

The city of Atlanta, Georgia, was an important rail and commercial center during the American Civil War. Although relatively small in population, the city became a critical point of contention during the Atlanta Campaign in 1864 when a powerful Union army approached from Union-held Tennessee. The fall of Atlanta was a critical point in the Civil War, giving the North more confidence, and (along with the victories at Mobile Bay and Winchester) leading to the re-election of President Abraham Lincoln and the eventual surrender of the Confederacy. The capture of the "Gate City of the South" was especially important for Abraham Lincoln as he was in a contentious election campaign against the Democratic opponent George B. McClellan.[1]

Early war years

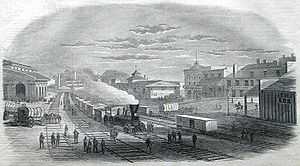

The city that would become Atlanta began as the endpoint of the Western and Atlantic Railroad (aptly named Terminus) in 1837.[2][3] Atlanta grew quickly with the completion of The Georgia Railway in 1845[4] and the Macon & Western in 1846.[5] The city was incorporated in 1847 and extended 1 mile in all directions from the zero-mile post.[6] In 1860, Atlanta was a relatively small city ranking 99th in the United States in size with a population of 9,554 according to the 1860 United States (U.S.) Census. However, it was the 12th-largest city in what became the Confederate States of America. A large number of machine shops, foundries and other industrial concerns were soon established in Atlanta. The population swelled to nearly 22,000 as workers arrived for these new factories and warehouses.

The city was a vital transportation and logistics center, with several major railroads in the area. The Western & Atlantic Railroad connected the city with Chattanooga, Tennessee, 138 miles to the north. The Georgia Railway connected the city with Augusta to the east and the Confederate Powderworks on the Savannah River.[7][8] The Macon & Western [9] connected Atlanta to Macon and Savannah to its south. The fourth line, Atlanta and West Point Railroad, completed in 1854, connected Atlanta with West Point, Georgia.[10] At West Point the line linked up with the Western Railway of Alabama, thus connecting Atlanta with Montgomery to its west. A series of roads radiated out from the city in all directions, connecting Atlanta with neighboring towns and states.

Thought to be relatively safe from Union forces early in the war, Atlanta rapidly became a concentration point for the Confederate quartermasters and logistics experts;[11][12] warehouses were filled with food, forage, supplies, ammunition, clothing and other materiel critical to the Confederate States of America armies operating in the Western Theater.

Some of the major manufacturing facilities supporting the confederate war effort were:[13][14]

- The Atlanta Rolling Mill, established before the war, was significantly expanded and provided a major source for armor plating for Confederate Navy ironclads, including the CSS Virginia. It also refurbished railroad tracks.

- The Confederate Pistol Factory made pistols.

- The Novelty Iron Works produced ordinance supplies.

- Confederate Arsenal was located at the northwest corner of Walton and Peachtree Street.

- The Empire Manufacturing Company made Railroad cars and bar iron.

- Winship Foundry produced great quantities of metal products, railroad supplies, freight cars, and iron bolts.

- Atlanta Machine Works produced ordnance. The cannons produced by the Atlanta Machine Works were rifled at the Western and Atlantic Roundhouse.

- W. S. Withers and Solomon Solomon Foundry made buttons, spurs, bits, buckles, etc.

- A Flour Mill was located at the northwest corner of Marietta and North Avenue.

- Hammond Marshall Sword Factory manufactured swords.

- Atlanta Steam Tannery made leather goods for the army.

- The Naval Ordnance Works was set up in early 1862 by Lieutenant David Porter McCorkle using stores and machinery he was able to move to Atlanta from New Orleans before it fell. The works produced gun carriages and 7 inch shells for the Confederate navy.[15]

- The Confederate Iron and Brass Foundry produced all kinds of iron and brass works.

In addition to the transportation and manufacturing facilities, there were several hospitals in Atlanta.[16]

- The General Hospital was located on the fairground, on Fair Street.

- The Distribution Hospital was located on the southeast corner of Alabama and Pryor Streets.

- The Atlanta Female Institute on Courtland Street was used as a hospital.

- The Atlanta Medical College was used as a surgical hospital.

- Kiles Hotel on Decatur and Loyd Streets was used as a hospital.

- A hotel on Peachtree was used as a hospital.

- The convalescent hospital was located on the Ponder property at Means Street and Ponder Avenue.

- The hospital for contagious diseases was located on 155 acres of property taken from William Markham.

On July 5, 1864, Gen. Joseph E. Johnston issued orders that all hospitals and munitions works in Atlanta be evacuated. On July 7, Colonel Josiah Georgas, ordnance chief in Richmond, issued orders to Colonel M. H. Wright, Commanding the arsenal in Atlanta: "Send the bulk of machinery & stores to Augusta and to Columbia, S.C., send workmen in same direction when it becomes necessary." [17][18]

A number of newspapers flourished in Atlanta during the Civil War. Among the more prominent ones were the Atlanta Southern Confederacy and the Daily Intelligencer, both of which moved to Macon, Georgia during the Union occupation in 1864. The Daily Intelligencer was the only Atlanta paper to survive the war and resume publication from Atlanta after Union forces began their "March to the Sea".[19][20][21]

Atlanta as a target

Concerned after the fall of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, that Atlanta would be a logical target for future Union Army attacks, Jeremy F. Gilmer, Chief of the Confederate Engineer Bureau, contacted Captain Lemuel P. Grant, Chief Engineer of the Department of Georgia, and asked him to survey possible enemy crossings of the Chattahoochee River, a broad waterway that offered some protection from a Northern approach. Grant complied, and after a thorough investigation and survey, explained that the fortification of Atlanta would involve "an expenditure second only to the defense of Richmond". Captain Grant planned "a cordon of enclosed works, within supporting distance of each other", with twelve to fifteen strong forts sited specially for artillery and connected by infantry entrenchments in a perimeter "between 10 and 12 miles in extent". Gilmer gave Grant the approval to develop a plan to ring Atlanta with forts and earthworks along the key approaches to the city. Gilmer advised that the earthen forts should be connected by a line of rifle pits, with ditches, felled timbers or other obstruction to impede an infantry charge. Gilmer also suggested that the perimeter should be "far enough from the town to prevent the enemy coming within bombarding distance" [22][23]

General Gilmer knew that the construction of the Atlanta Fortification would, by its scope, impact private property. He advised Col. M. J. Wright:[24]

HEADQUARTERS, ETC.,

Charleston, S. C., October 21, 1863.Col. M. J. WRIGHT

Commanding, Atlanta, Ga.:COLONEL: In order to make the works constructed for the defense of Atlanta effective, the timber must be cut down in front of the lines for a distance of, say, 900 to 1,000 cubic yards, and the cutting should be continuous.

The true rule should be to clear away as far as our own guns can (command the ground, well and no farther, as the ranges of the enemy's artillery are generally greater than ours. The work ought to be commenced at once, as it will require some time to complete it; the forest in front of the batteries to be cleared away first. In all cases have the trees thrown from the lines and the branches that stand up from the felled trees cut off so that they may offer no cover. The stumps ought not to be high.

As to damages for putting up works on private lands and cutting timber, they should be assessed by impartial and intelligent persons. A good plan (one that we have resorted to in previous cases) is to appoint an officer of good judgment and the local proprietors to select a second, to make the appraisements and report the same to the engineer officer (Captain Grant) for transmission to the Engineer Bureau. That office will have the appraisement examined and make such indorsements thereon as may be thought just and proper, and then forward them to the Attorney-General, whose duty it is by law to examine them, and, if the claims be well founded, to ask Congress to appropriate for their payment. Should the two appraisers fail to agree they must choose a third as umpire. In each case the property damaged should be described with care. I would like to have the indorsements of yourself and Captain Grant on the appraisements before they are forwarded to the Engineer Bureau.

It is not necessary to apply to Richmond concerning the exterior lines. If you have the labor, press them forward at once, particularly on the front. Direct Captain Grant to apply to the Engineer Bureau for all necessary funds. If needed a reasonable supply of intrenching tools, axes, &c., can be sent him on his application, but I hope you have sufficient from the battle-field of Chickamauga.

I am, colonel, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

J. F. GILMER,

Major-General and Chief of Engineer Bureau

Captain Grant planned a series of 17 redoubts forming a 10-mile (16 km) circle over a mile (1.6 km) out from the center of town. These would be interlinked with a series of earthworks and trenches, along with rows of abatis and other impediments to enemy troops. Construction on the extensive defensive works began in August 1863. They were bounded on the north by high ground (the present location of the Fox Theatre), the west by Ashby Street, the south by McDonough Drive and the east by what is today known as Grant Park. Gilmer inspected the completed work in December 1863 and gave his approval.[25] Because of how the subsequent campaign unfolded, most of these fortifications were never really put to the test.[26][27]

By late October Captain Grant had nearly completed his encirclement of Atlanta and the number of forts had risen to seventeen. Of the seventeen planned forts, thirteen had been completed. Due to topographical features of the land and the manning requirements for the fortifications, Grant's design had, by necessity, left Atlanta within artillery range. The section of the line protecting the North West approach to Atlanta was actually inside the city limits. To help protect this area, an additional string of forts was constructed further out from the city. A report from Captain Grant to Gen. Wright places the length of the fortifications at 10 ½ miles and requiring about 55,000 troops to fully man the line.[28][29]

In addition to the fortifications surrounding Atlanta, the local militia was reorganized by Brig. Gen. M. J. Wright during March 1864. The militia was "composed exclusively of detailed soldiers and exempts, all those liable to conscription". The total strength was 534 men.[30]

Siege of Atlanta (July – August, 1864)

In the spring of 1864, the Confederate Army of Tennessee, commanded by General Joseph E. Johnston, was entrenched near the city of Dalton, Georgia. In early May, 1864, Union forces under the command of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman began the Atlanta Campaign. By early July the Confederate forces had been forced back to the outskirts of Atlanta. Both the Union and Confederate forces used the Western & Atlantic Railroad to supply their troops.

The last remaining natural obstacle separating the Union forces from Atlanta was the Chattahoochee River. By July 9, the Federal forces had secured 3 good crossings over the Chattahoochee, one at Powers’ Ferry, a second at the mouth of Soap Creek and a third at the shallow ford near Roswell, GA. The federal forces rested and moved troops around to prepare for their advance on the city of Atlanta beginning on July 16. [31] [32]

On July 10, Maj. Gen. Sherman sent orders via telegraph to Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau then stationed at Decatur, AL, with a force of 2,500 cavalry to cut the rail line linking Atlanta with Montgomery, AL. On July 16th, Gen. Rousseau´s men cut about 25 miles of the rail line, west of Opelika, AL, as well as three miles of the branch toward Columbus, GA, and two miles towards West Point, Georgia. Gen. Rousseau’s Calvary force then joined General Sherman inMarietta, GA, on July 22. [33]

Union Calvary forces under the command of Brig. Gen. Kenner Garrard supported by a brigade of infantry cut the Georgia Railroad that connected Atlanta with Augusta, GA., near the town of Stone Mountain, GA, on July 18, 1864. [34][35]

On July 18, 1864, General Joseph E. Johnston was relieved of command of the Confederate forces. General John Bell Hood was given command of the Army of Tennessee. [36]

General Sherman issued Special Order 39, detailing the Union advance on Atlanta on July 19, 1864. [37]

HDQR. Mil. Div. OF THE MISS.Special Order

In the Field, near Decatur, Ga.,No. 39.

July 19, 1864.

The whole army will move on Atlanta by the most direct roads tomorrow, July 20, beginning at 5 a. m., as follows:

I. Major-General Thomas from the direction of Buck Head, his left to connect with General Schofields right about two miles northeast of Atlanta, about lot 15, near the houses marked as Hu. and Col. Hoo.

II. Major-General Schofield by the road leading from Doctor Powell’s to Atlanta.

III. Major-General McPherson will follow one or more roads direct from Decatur to Atlanta, following substantially the railroad.Each army commander will accept battle on anything like fair terms, but if the army reach within cannon-range of the city without receiving artillery or musketry fire he will halt, form a strong line, with batteries in position, and await orders. If fired on from the forts or buildings of Atlanta no consideration must be paid to the fact that they are occupied by families, but the place must be cannonaded without the formality of a demand.

The general-in-chief will be with the center of the army, viz, with or near General Schofield.

By order of Maj. Gen. W. T. Sherman:

L. M. DAYTON, aide-de-Camp.

With the Union forces spread out over such a wide front, General Hood launched an attack against the Union right at Peachtree Creek on July 20, 1864. The Confederate advance was repulsed at the Battle of Peach Tree Creek. [38][39] The Confederates then launched a second attack on July 22, this time against the Union, left east of Atlanta near the Augusta railroad. The Confederates were again repulsed with heavy losses at the Battle of Atlanta. [40] During the Battle of Atlanta Union General James B. McPherson and Confederate General William H. T. Walker were killed. [41] [42] [43] General Sherman had now cut two of the four rail lines leading into Atlanta.

In an effort to cut the Confederate supply lines between West Point, GA, and Atlanta, General Sherman moved forces along the west side of Atlanta. General Hood sent two of his Corps to protect his supply lines. Expecting an attack, the Union forces entrenched near Ezra Church. The Confederates attacked on July 28, and were repulsed in the Battle of Ezra Church. Even though the Union forces were victorious in the Battle of Ezra Church, the Union forces failed to cut the rail line supplying Atlanta from west Point. [44]

The Union forces continued to move south on the west side of Atlanta, but the Confederates were able to extend their lines to match these movements. The two sides once again clashed on August 4–7, at Utoy Creek. The Union forces were repulsed with heavy losses and failed in an attempt to break the Atlanta and West Point Railroad.[45] [46]

On July 20, 1864, Battery H, First Illinois Light Artillery commanded by Capt. Francis De Gress, came into battery near the Troup Hurt Home. Capt. De Gress opened fire on downtown Atlanta from this point. He reported that: [47][48]

Advanced on the 20th, taking up position several times during the day and engaging rebel batteries. At 1 o’clock fired three shells into Atlanta at a distance of two miles and a half, the first ones of the war.— Capt. Francis De Gress, O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 3, OR# 486, page 265

The shelling of Atlanta [49] would continue from July 20, until August 25. [50] In addition to the cannons the Union forces had with them, four 4-1/2 inch siege cannons were brought by rail from Chattanooga. These four cannons began firing on the city on August 10. [51] [52] In total, these 4 cannons fired over 4,500 rounds on Atlanta.[53] On August 9, 1864, General Sherman report that: [54]

Maj. Gen. II. W. HALLECK,

Washington, D. C.:

Schofield developed the enemy’s position to below East Point. His line is well fortified, embracing Atlanta and East Point, and his re-doubts and lines seem well filled. Cavalry is on his flanks. Our forces, too, are spread for ten miles. So Hood intends to stand his ground. I threw into Atlanta about 3,000 solid shot and shell to-day, and have got from Chattanooga four 4-1/2 Inch rifled guns, and will try their effect. Our right is below Utoy Creek. I will intrench it and the flanks and study time ground a little more before adopting a new plan. We have had considerable rain, but on the whole the weather is healthy. Colonel Capron, of Stoneman’s command, with several squads of men are in at Marietta, and will reduce his loss below 1,000.

W. T. SHERMAN,Major-General.

There are no official records of the number of people killed by the bombardment of Atlanta. [55]

During the early part of August several attempts were made to cut the two remaining rail lines to Atlanta using Calvary. Even though the Union Calvary successfully tore up sections of the rail line, they were not able to do sufficient damage to prevent the Confederate forces from easily repairing the affected sections of railroad. [56] Union forces also continued to probe the Confederate lines looking for weak spots. Even though no frontal assault was ever made on Atlanta there was a constant skirmishing between the lines and casualties occurred on both sides. [57]

On August 20, the Atlanta and West Point Railroad was cut near Red Oak Station. [58] On August 25, [59] the Union forces withdrew from their entrenchments around Atlanta. Part of the Union forces pulled back to prepare defensive positions at the Chattahoochee River while the remainder of the Union forces marched south of Atlanta to attack the Macon & Western Railroad. [60] On August 31-September 1, the Confederate forces once again failed to stop the Union troops at the Battle of Jonesboro. [61]

With all of his supply lines cut, General Hood was forced to abandon Atlanta. On the night of September 1, his troops marched out of the city toLovejoy, Georgia. General Hood ordered that the 81 rail cars filled with ammunition and other military supplies be destroyed. The resulting fire and explosions were heard for miles. [62] In his Official Report, General Sherman stated: [63]

... About 2 o'clock that night the sounds of heavy explosions were heard in the direction of Atlanta, distant about twenty miles, with a succession of minor explosions and what seemed like the rapid firing of cannon and musketry. These continued about an hour, and again about 4 a.m. occurred another series of similar discharges apparently nearer us, and these sounds could be accounted for on no other hypothesis than of a night attack on Atlanta by General Slocum or the blowing up of the enemy s magazines. Nevertheless at daybreak, on finding the enemy gone from his lines at Jonesborough, I ordered a general pursuit south, General Thomas following to the left of the railroad, General Howard on its right, and General Schofield keeping off about two miles to the east. We overtook the enemy again near Lovejoy's Station in a strong intrenched position, with his flanks well protected behind a branch of Walnut Creek to the right and a confluent of the Flint River to his left. We pushed close up and reconnoitered the ground and found he had evidently halted to cover his communication with the McDonough and Fayetteville road.— William T. Sherman, Official Report of the Atlanta Campaign

On September 2, Mayor James M. Calhoun surrendered the city of Atlanta to the Union Army. [64]

The fall of Atlanta

In 1864 the city, as feared by Gilmer, did indeed become the target of a major Union invasion. The area now covered by metropolitan Atlanta was the scene of several fiercely contested battles, including the Battle of Peachtree Creek, the Battle of Atlanta, Battle of Ezra Church and the Battle of Jonesboro. On September 1, 1864, Confederate General John Bell Hood evacuated Atlanta, after a five-week siege mounted by Union General William Sherman, and ordered all public buildings and possible Confederate assets destroyed.

On September 2, Mayor James Calhoun surrendered the city.[65][66] Sherman sent a telegram to Washington reading, "Atlanta is ours, and fairly won" and he established his headquarters there on September 7, where he stayed for two months. That same day, Sherman ordered the civilian population to evacuate.[67]

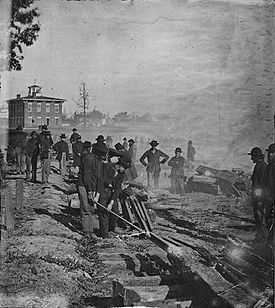

After a plea by Father Thomas O'Reilly[68] of the Immaculate Conception Catholic Church, Sherman did not burn the city's churches or hospitals. However, the remaining war resources were then destroyed in the aftermath and in Sherman's March to the Sea. These included Edward A. Vincent's railroad depot, built in 1853. As General Sherman departed Atlanta at 7:00 a.m. on November 15 with the bulk of his army, he noted his handiwork:

... We rode out of Atlanta by the Decatur road, filled by the marching troops and wagons of the Fourteenth Corps; and reaching the hill, just outside of the old rebel works, we naturally paused to look back upon the scenes of our past battles. We stood upon the very ground whereon was fought the bloody battle of July 22d, and could see the copse of wood where McPherson fell. Behind us lay Atlanta, smouldering and in ruins, the black smoke rising high in air, and hanging like a pall over the ruined city.— William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman, Chapter 21

Aftermath

The fall of Atlanta was especially noteworthy for its political ramifications. The capture and fall of Atlanta were extensively covered by Northern newspapers, and significantly boosted Northern morale. Lincoln was re-elected easily.

Following the war Federal troops returned to Atlanta to help enforce the provisions of Reconstruction.

References

- ↑ Pollock, Daniel A. (May 30, 2014). "The Battle of Atlanta: History and Remembrance". Southern Spaces. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ↑ New Georgia Encyclopedia, Atlanta

- ↑ Cooper, Official History of Fulton County, pp 36-38

- ↑ Cooper, Official History of Fulton County, p 597

- ↑ Cooper, Official History of Fulton County, p 592

- ↑ Cooper, Official History of Fulton County, p 64

- ↑ Cooper, Official History of Fulton County, p 597

- ↑ Internet Archive, History of the Confederate powder works

- ↑ Cooper, Official History of Fulton County, p 592

- ↑ Cooper, Official History of Fulton County, p 599

- ↑ Cooper, Official History of Fulton County, p 177

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, p 532

- ↑ Cooper, Official History of Fulton County, p 144

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, p 532

- ↑ Davis, What the Yankee's did to Us, p 42

- ↑ Cooper, Official History of Fulton County, p 9 116-117

- ↑ Davis, What the Yankee's did to Us, p 77

- ↑ Shavin, Norman (1964). The Atlanta Century March 1860-May 1865. Capricorn Corporation. p. Vol. 5, No. 21.

- ↑ Cooper, Official History of Fulton County, p 328

- ↑ Davis, What the Yankee's did to Us, p 83

- ↑ Shavin, Norman (1964). The Atlanta Century March 1860-May 1865. Capricorn Corporation. p. Vol. 5, No. 21.

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, p 567

- ↑ Davis, What the Yankee's did to Us, pp 58-59

- ↑ OR Series 1 - Volume 31 (Part III) pp 575-576

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, p 532

- ↑ Davis, What the Yankee's did to Us, pp 58-63

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, p 568

- ↑ Davis, What the Yankee's did to Us, pp 58-63

- ↑ [url=http://historyatlanta.com/fort-x/]| History Atlanta, Fort X

- ↑ OR Series 1 - Volume 32 (Part III), p 740

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, O.R. 1, pp 70-72.

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, pp 597-603

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, OR # 1, pp 70-71: Part 2, OR #431 PP 904-911

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 2, OR # 398 P 804

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, p 609

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 5 - Union and Confederate Correspondence, etc., p 891

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 5 - Union and Confederate Correspondence, etc., p 193

- ↑ Cooper, Official History of Fulton County p 123

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, pp 612-614

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, part 1 pages 52-54

- ↑ Cooper, Official History of Fulton County pp 146-152

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, OR 1 p 75

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, p 617

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, OR # 1, p 77-79

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, pp 625-626

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, OR # 1, p 77-79

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, pp 620-621

- ↑ Davis, The Day Dixie Died, pp 28-29

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 5 - Union and Confederate Correspondence, etc., Special Order 41, pp 232-233

- ↑ Davis, What the Yankee's did to Us, p 97

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 5 - Union and Confederate Correspondence, etc., page 449

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, p 625

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 3, # OR 4, p 123

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 5 - Union and Confederate Correspondence, etc., p 434

- ↑ Davis, What the Yankee's did to Us, p 243

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, OR # 1, p 80

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, pp 990-925

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, OR #6, p 135

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, p 925

- ↑ O.R. Series I, Volume 38, Part 1, OR #6 p 135, Appendix; IV Corps. Journal, p 925 and Part 5 - Union and Confederate Correspondence, etc., Special Field Order 57, p 546

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, OR # 1, p 80

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, pp 433-634

- ↑ O.R. Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, OR # 1, p 82

- ↑ Garrett, Atlanta and Environs, P 634

- ↑ Upper Marietta Street Artery website

- ↑ Garrett, ‘‘Atlanta and Environs’’, 1954 p. 634

- ↑ Correspondence Pertaining to Sherman's Evacuation of Atlanta reproduced at civilwarhome.com.

- ↑ Garrett, ‘‘Atlanta and Environs’’, 1954 p. 654

Further reading

- Bonds, Russell S. (2009). War like the thunderbolt: the battle and burning of Atlanta. Westholme. ISBN 1594161003. OCLC 370356386.

- Dodge, Grenville M. (1910). The battle of Atlanta and other campaigns, addresses, etc. Monarch Print. Co. OCLC 2055872.

- Swan, James B. (2009). Chicago's Irish Legion: the 90th Illinois Volunteers in the Civil War. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0809328909. OCLC 232327691.

- Garrett, Franklin M. (1954). Atlanta and Environs, A Chronicle of its People and Events. Lewis Historical Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0820309132.

- Ecelbarger, Gary (2010). The Day Dixie Died: The Battle of Atlanta. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-56399-8.

External links

- A brief history of the American Civil War

- Who Burned Atlanta?

- Atlanta as Left by Our Troops

- Fort X

- The New Georgia Encyclopedia - Atlanta

- Touring itinerary of modern Atlanta's Civil War sites and places

- Atlanta Cyclorama and Civil War Museum

- University of Georgia website for Georgia in the Civil War

- Civil War Sites in Georgia

- General William T. Sherman's order to evacuate Atlanta, (Special Field Orders No. 67), 4 September 1864. From the collection of the Georgia Archives.

- Civil War records available for research at the National Archives at Atlanta

- Webcast Lecture by Russell S. Bonds author of War Like the Thunderbolt at the Pritzker Military Library on May 6, 2010

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||