Assured Clear Distance Ahead

The Assured Clear Distance Ahead (ACDA) is the distance ahead of a vehicle or craft which can be seen to be clear of hazards by the driver, within which they should be able to bring the vehicle to a halt. It is one of the most fundamental principles governing ordinary care and the duty of care and is frequently used to determine if a driver is in proper control and is a nearly universally implicit consideration in vehicular accident liability.[1][2][3]

This distance is typically both determined and constrained by the proximate edge of clear visibility, but it may be attenuated to a margin of which beyond hazards may reasonably be expected to spontaneously appear. It is a spatial component to the common law basic speed rule. The two-second rule may be the limiting factor governing the ACDA, when the speed of forward traffic is what limits the basic safe speed, and a primary hazard of collision could result from following any closer.

ACDA as Common Law Rule or Statute

"At common law a motorist is required to regulate his speed so that he can stop within the range of his vision. In numerous jurisdictions, this rule has been incorporated in statutes which typically require that no person shall drive any motor vehicle in and upon any public road or highway at a greater speed than will permit him to bring it to a stop within the assured clear distance ahead."[1] Decisional law usually settles the circumstances by which a portion of the roadway is assuredly clear without it being mentioned in statute.[4] California is a state where the judiciary has established the state's ACDA law.[5][6][7][8][9][Note 1] Most state issued driver handbooks either instruct or mention the ACDA rule as required care or safe practice.[10][11][12][13][14]

Many states have further passed statutes which require their courts to more inflexibly weigh the ACDA in their determination of reasonable speed or behavior. Such statutes do so in part by designating ACDA violations as a citable driving offense, thus burdening an offending driver to rebut a presumption of negligence. States with such explicit ACDA standard of care provisions include: Iowa,[15] Michigan,[16] Ohio,[17] Oklahoma,[18] and Pennsylvania.[19] States which apply the principle by statute to watercraft on navigable waterways include: Montana,[20] Florida,[21] and West Virginia. Explicit ACDA statutes, especially those of which create a citable driving offense, are aimed at preventing harm that could result from potentially negligent behavior—whereas the slightly more obscure common law ACDA doctrine is most easily invoked to remedy actual damages that have already occurred as a result of such negligence. Explicit and implicit ACDA rules govern millions of North American drivers.

Determining the ACDA

Static "line-of-sight" distance

The range of visibility of which is the de facto ACDA, is usually that distance before which an ordinary person can see small hazards—such as a traffic cone or buoy—with 20/20 vision. This distance may be attenuated by specific conditions such as atmospheric opacity, blinding glare, and adjacent environmental hazards including civil and recreational activities, deer, livestock, and parked cars. The ACDA may also be somewhat attenuated on roads with lower functional classification.[22] [23] This is because the probability of spontaneous traffic increases proportionally to the density of road access points, and this density reduces the distance a person exercising ordinary care can be assured that a road will be clear; such reduction in the ACDA is readily apparent from the conditions, even when a specific access point or the traffic thereon is not.[24][Note 2] Furthermore, even though a through-driver may typically presume all traffic will stay assuredly clear when required by law, such driver may not take such presumption when circumstances provide actual knowledge under ordinary care that such traffic cannot obey the law.[24]

Dynamic "following" distance

The ACDA may also be dynamic as to the moving distance past which a motorist can be assured be to able to stay clear of a foreseeable dynamic hazard—such as to maintain a distance as to be able to safely swerve around a bicyclist should he succumb to a fall—without requiring a full stop beforehand, if doing so could be exercised with due care towards surrounding traffic. Quantitatively this distance is a function of the appropriate time gap and the operating speed: dACDA=tgap*v. The assured clear distance ahead rule, rather than being subject to exceptions, is not really intended to apply beyond situations in which a vigilant ordinarily prudent person could or should anticipate.[1]

As such, the Assured Clear Distance Ahead is somewhat subjective to the baseline estimate of a reasonable person. For example, whether one should have reasonably foreseen that a road was not assuredly clear past 75–100 meters because of tractors or livestock which commonly emerge from encroaching blinding vegetation is on occasion dependent on societal experience within the locale. In urban environments, a straight, traffic-less, through-street may not necessarily be assuredly clear past the entrance of the nearest visually obstructed intersection.[22][23][24]

Relation to the basic speed rule

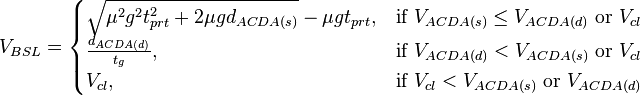

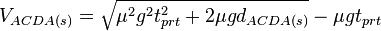

The ACDA distances are a principal component to be evaluated in the determination of the maximum safe speed (VBSL) under the basic speed law, without which the maximum safe speed cannot be determined. The relation of the ACDA to the basic speed rule may be objectively quantified as follows:

The maximum velocity permitted by the Assured Clear Distance Ahead is controlling for only the top and middle cases.

For the top case, the maximum speed is governed by the assured clear "line-of-sight", as when the "following distance" aft of forward traffic and "steering control" are both adequate. Common examples include when there is no vehicle to be viewed, or when there is a haze or fog that would prevent visualizing a close vehicle in front. This maximum velocity is denoted by the case variable  , the friction coefficient is symbolized by

, the friction coefficient is symbolized by  —and itself a function of the tire type and road conditions, the distance

—and itself a function of the tire type and road conditions, the distance  is the static ACDA, the constant

is the static ACDA, the constant  is the acceleration of gravity, and interval

is the acceleration of gravity, and interval  is the perception-reaction time—usually between 1.0 and 2.5 seconds.[25]

is the perception-reaction time—usually between 1.0 and 2.5 seconds.[25]

The pedantic middle case applies when the dynamic ACDA "following distance" (dACDA(d)) is less than the static ACDA "line-of-sight" distance (dACDA(s)). A classic instance of this occurs when, from a visibility perspective, it would be safe to drive much faster were it not for a slower-moving vehicle ahead. As such, the dynamic ACDA is governing the basic speed rule, because in maintaining this distance, one cannot drive at a faster speed than that matching the forward vehicle. The "time gap" tg or "time cushion" is the time required to travel the dynamic ACDA or "following distance" at the operating speed. Circumstances depending, this cushion might be manifested as a two-second rule or three-second rule.

The bottom case is invoked when the maximum velocity for surface control Vcl is otherwise reached. Steering control is independent from any concept of clear distance ahead. If a vehicle cannot be controlled so as to safely remain within its lane above a certain speed and circumstance, then it is irrelevant how assuredly clear the distance is ahead.

Notes

- ↑ In addition to being old common law principle, ACDA case law jurisprudence buttressed the legislature's implicit intent in its' Basic Speed Law, and further limited transference of liability for ACDA negligence to the state—under the California Tort Claims Act—for insufficient sight distance at the speed of which the driver chose. See CVC § 22350, CVC § 22358.5, Cal Gov. Code § 830.4, Cal Gov. Code § 830.8, and Cal Gov. Code § 831. See CACI Form 1120 for details.

- ↑ For this reason, full corner sight distance is almost never required for individual driveways in urban high-density residential areas, and street parking is commonly permitted within the right-of-way.

- ↑ In most jurisdictions, judicial notice shall be taken of the total stopping distance, and such notice is therefore logically and substantively taken of the maximum speed permitted to brake within the stopping distance as applied to the ACDA. The latter is merely the inverse function of the former. Furthermore, fundamental mathematical relationships are themselves subject to judicial notice.

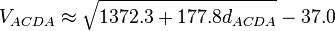

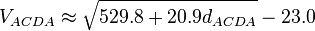

For example, using the

For example, using the  and

and  values that produced Code of Virginia § 46.2-880 Tables of speed and stopping distances, one simply obtains the same velocities that produced the stopping distance in the statute:

Metric (SI) – Speed in km/h from distance in meters:

values that produced Code of Virginia § 46.2-880 Tables of speed and stopping distances, one simply obtains the same velocities that produced the stopping distance in the statute:

Metric (SI) – Speed in km/h from distance in meters:

US customary – Speed in MPH from distance in feet:

US customary – Speed in MPH from distance in feet:

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 James O. Pearson (2009). "Automobiles: sudden emergency as exception to rule requiring motorist to maintain ability to stop within assured clear distance ahead". American Law Reports--Annotated, 3rd Series 75. The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company; Bancroft-Whitney; West Group Annotation Company. p. 327.

- ↑ "Assured Clear Distance Ahead--Law & Legal Definition". US Legal. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

- ↑ Leibowitz, Herschel W.; Owens, D. Alfred; Tyrrell, Richard A. (1998). "The assured clear distance ahead rule: implications for nighttime traffic safety and the law". Accident Analysis 30 (1): 93–99. doi:10.1016/S0001-4575(97)00067-5.

- ↑ "O’Farrell v. Inzeo, 74 A.D.2d 806 (1st Dept. 1980)". Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of the State of New York.

- ↑ "Satterlee v. Orange Glenn School Dist., 29 Cal.2d 581". Official California Reports, 2nd Series (California Supreme Court; Bancroft-Whitney; LexisNexis) 29: 581. Jan 31, 1947. Retrieved 2013-09-01.

proper conduct of a reasonable person under particular situations may become settled by judicial decision or be prescribed by statute or ordinance.

See California Official Reports: Online Opinions - ↑ "Lutz v. Schendel, 175 Cal. App. 2d 140". Official California Appellate Reports, 2nd Series (California Appellate Court; Bancroft-Whitney; LexisNexis) 175: 140. Nov 6, 1959. Retrieved 2013-09-01.

It is the duty of the driver of a motor vehicle using the public highways to be vigilant at all times and to keep the vehicle under such control that to avoid a collision he can stop as quickly as might be required of him by eventualities that would be anticipated by an ordinarily prudent driver in like position.

See California Official Reports: Online Opinions - ↑ "Falasco v. Hulen, 6 Cal. App. 2d 224". Official California Appellate Reports, 2nd Series (California Appellate Court; Bancroft-Whitney; LexisNexis) 6: 224. April 17, 1935. Retrieved 2013-09-01.

"Driving between 60 and 65 miles an hour over the brow of a hill, where one's view is obstructed and one cannot see what is on the opposite side of the hill for a sufficient distance to control the speed of his car, is an act showing a reckless disregard of the safety of others; and in said action, under the evidence, the jury was entitled to conclude either that defendant was driving at such a reckless rate of speed that he could not control the car, or that he was driving at such a high rate of speed that he did not perceive that the highway ahead of him afforded an unobstructed passage." (CA Reports Official Headnote #[9])

See California Official Reports: Online Opinions - ↑ "Cannon v. Kemper, 23 Cal. App. 2d 239". Official California Appellate Reports, 2nd Series (California Appellate Court; Bancroft-Whitney; LexisNexis) 23: 239. October 21, 1937. Retrieved 2013-09-01. Driver traveling at 35 MPH when rain limited visibility to 25 feet held negligent when 65 feet were required to stop car on wet road. See California Official Reports: Online Opinions

- ↑ "Bove v. Beckman, 236 Cal. App. 2d 555". Official California Appellate Reports, 2nd Series (California Appellate Court; Bancroft-Whitney; LexisNexis) 236: 555. Aug 16, 1965. Retrieved 2013-09-01.

"A person driving an automobile at 65 miles an hour on a highway on a dark night with his lights on low beam affording a forward vision of only about 100 feet was driving at a negligent and excessive speed which was inconsistent with any right of way that he might otherwise have had." (CA Reports Official Headnote #[8])

See California Official Reports: Online Opinions - ↑ Alaska Driver Manual (PDF). State of Alaska. p. 28.

A person may not drive a vehicle upon a highway at a speed greater than will permit them to stop within the assured clear distance ahead

- ↑ Driver's Manual (PDF). Oklahoma Department of Public Safety. p. 8-2.

- ↑ Driver's Manual (PDF). Iowa Department of Transportation. p. 39.

- ↑ Road Users Manual (PDF). Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. p. 49.

- ↑ Road Users Manual (PDF). Prince Edward Island, Canada. p. 88.

- ↑ "Code § 321.285 Speed restrictions.". State of Iowa. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ↑ "§ 257.627 Speed limitations". State of Michigan. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Revised Code § 4511.21(A) Speed limits - assured clear distance". State of Ohio. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ↑ "§ 47-11-801". State of Oklahoma. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ↑ "75 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 3361. Driving vehicle at safe speed". State of Pennsylvania. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ↑ "§ 23-2-523(4). Prohibited operation and mooring -- enforcement". State of Montana. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Boating Safety".

Excessive speed is a rate of speed greater than is reasonable or prudent without regard for conditions and hazards or greater than will permit a person to bring the boat to a stop within the assured clear distance ahead.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Riggs v. Gasser Motors, 22 Cal. App. 2d 636". Official California Appellate Reports (2nd Series Vol. 22, p. 636). September 25, 1937. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

"It is common knowledge that intersecting streets in cities present a continuing hazard, the degree of hazard depending upon the extent of the use of the intersecting streets and the surrounding circumstances or conditions of each intersection. Under such circumstances the basic law...is always governing."

See Official Reports Opinions Online - ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Reaugh v. Cudahy Packing Co., 189 Cal. 335". Official California Reports, Vol. 189, p. 335, (California Supreme Court reporter). July 27, 1922. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

"motor vehicles, must be specially watchful in anticipation of the presence of others at places where other vehicles are constantly passing, and where men, women, and children are liable to be crossing, such as corners at the intersections of streets or other similar places or situations where people are likely to fail to observe an approaching automobile."

See Official Reports Opinions Online - ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "Leeper v. Nelson, 139 Cal. App. 2d 65". Official California Appellate Reports (2nd Series Vol. 139, p. 65). Feb 6, 1956. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

"The operator of an automobile is bound to anticipate that he may meet persons or vehicles at any point of the street, and he must in order to avoid a charge of negligence, keep a proper lookout for them and keep his machine under such control as will enable him to avoid a collision with another automobile driven with care and caution as a reasonably prudent person would do under similar conditions."

See Huetter v. Andrews, 91 Cal. App. 2d 142, Berlin v. Violett, 129 Cal.App. 337, Reaugh v. Cudahy Packing Co., 189 Cal. 335, and Official Reports Opinions Online - ↑ Taoka, George T. (March 1989). "Brake Reaction Times of Unalerted Drivers" (PDF). ITE Journal 59 (3): 19–21.

Further reading: tertiary sources

ACDA related law reviews

- James O. Pearson (2009). "Automobiles: sudden emergency as exception to rule requiring motorist to maintain ability to stop within assured clear distance ahead". American Law Reports--Annotated, 3rd Series 75. The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company; Bancroft-Whitney; West Group Annotation Company. p. 327.

- W. R. Habeeb (2010). "Liability for motor vehicle accident where vision of driver is obscured by smoke, dust,atmospheric condition, or unclean windshield". American Law Reports--Annotated, 2nd Series 42. The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company; Bancroft-Whitney; West Group Annotation Company. p. 13.

- Wade R. Habeeb (2009). "Liability or recovery in automobile negligence action as affected by driver's being blinded by lights other than those of a motor vehicle". American Law Reports--Annotated, 3rd Series 64. The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company; Bancroft-Whitney; West Group Annotation Company. p. 760.

- Wade R. Habeeb? (c. 2009). "Liability or recovery in automobile negligence action as affected by driver's being blinded by lights of motor vehicle". American Law Reports--Annotated, 3rd Series 64. The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company; Bancroft-Whitney; West Group Annotation Company. p. 551.

- L. S. Tellier (2011). "Right and duty of motorist on through, favored, or arterial street or highway to proceed where lateral view at intersection is obstructed by physical obstacle". American Law Reports--Annotated, 2nd Series 59. The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company; Bancroft-Whitney; West Group Annotation Company. p. 1202.

- ""Assured clear distance" statute or rule as applied at hill or curve". American Law Reports--Annotated 133. The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company; Bancroft-Whitney; West Group Annotation Company. p. 967.

- "Application of "assured clear distance ahead" or "radius of lights" doctrine to accident involving pedestrian crossing the street or highway". American Law Reports--Annotated, 2nd Series 31. The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company; Bancroft-Whitney; West Group Annotation Company. p. 1424.

- "Driving automobile at speed which prevents stopping within range of vision as negligence". American Law Reports--Annotated, 2nd Series. 44;58;87;97. The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company; Bancroft-Whitney; West Group Annotation Company. p. 1403;1493;900;546.

- "Driver's failure to maintain proper distance from motor vehicle ahead". American Law Reports--Annotated, 2nd Series 85. The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company; Bancroft-Whitney; West Group Annotation Company. p. 613.

- "Motor vehicle operator's liability for accident occurring while driving with vision obscured by smoke or steam". American Law Reports--Annotated, 4th Series 32. The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company; Bancroft-Whitney; West Group Annotation Company. p. 933.

- "Duty and liability of vehicle driver blinded by glare of lights". American Law Reports--Annotated, 2nd Series 22. The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company; Bancroft-Whitney; West Group Annotation Company. p. 292.

- "Liability for killing or injuring, by motor vehicle, livestock or fowl on highway". American Law Reports--Annotated, 4th Series 55. The Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company; Bancroft-Whitney; West Group Annotation Company. p. 822.

Other Printed Resources

- David A. Sklansky (2012-02-16). "Ch.9,11,&12". Evidence: Cases, Commentary and Problems (3 ed.). Aspen Publishers. ISBN 9781454806820.

- Marc Green et al. (2008). Forensic Vision with Application to Highway Safety (3 ed.). Lawyers & Judges Publishing Company, Inc. p. 454. ISBN 9781933264547.

Web Resources

See also

- Basic speed rule

- Braking distance

- Duty of Care

- Effects of insufficient sight distance

- Standard of care

- Two-second rule

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||