Aspect ratio (aerodynamics)

In aerodynamics, the aspect ratio of a wing is the ratio of its length to its breadth (chord). A high aspect ratio indicates long, narrow wings, whereas a low aspect ratio indicates short, stubby wings.[1]

For most wings the length of the chord is not a constant but varies along the wing, so the aspect ratio AR is defined as the square of the wingspan b divided by the area S of the wing planform,[2][3] which is equal to the length-to-breadth ratio for a constant chord wing. In symbols,

.

Aspect ratio of aircraft wings

Aspect ratio and planform can be used to predict the aerodynamic performance of a wing.

For a given wing area, the aspect ratio, which is proportional to the square of the wingspan, is of particular significance in determining the performance. Roughly, an airplane in flight can be imagined to affect a circular cylinder of air with a diameter equal to the wingspan.[4] A large wingspan is working on a large cylinder of air, and a small wingspan is working on a small cylinder of air. For two aircraft of the same weight but different wingspans the small cylinder of air must be pushed downward by a greater amount than the large cylinder in order to produce an equal upward force. The aft-leaning component of this change in velocity is proportional to the induced drag. Therefore the larger downward velocity produces a larger aft-leaning component and this leads to larger induced drag on the aircraft with the smaller wingspan and lower aspect ratio.

The interaction between undisturbed air outside the circular cylinder of air, and the downward-moving cylinder of air occurs at the wingtips and can be seen as wingtip vortices.

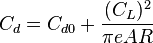

This property of aspect ratio AR is illustrated in the formula used to calculate the drag coefficient of an aircraft  [5][6][7]

[5][6][7]

where

is the aircraft drag coefficient

is the aircraft zero-lift drag coefficient,

is the aircraft lift coefficient,

is the circumference-to-diameter ratio of a circle, pi,

is the Oswald efficiency number

is the aspect ratio.

There are several reasons why not all aircraft have high aspect wings:

- Structural: A long wing has higher bending stress for a given load than a short one and therefore requires higher structural-design (architectural and/or material) specifications. Also, longer wings may have some torsion for a given load, and in some applications this torsion is undesirable (e.g. if the warped wing interferes with aileron effect).

- Maneuverability: a low aspect-ratio wing will have a higher roll angular acceleration than one of high aspect ratio, because a high-aspect-ratio wing has a higher moment of inertia to overcome. In a steady roll, the longer wing gives a higher roll moment because of the longer moment arm of the aileron. Low aspect ratio wings are usually used on fighter aircraft, not only for the higher roll rates, but especially for longer chord and thinner airfoils involved in supersonic flight.

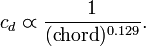

- Parasitic drag: While high aspect wings create less induced drag, they have greater parasitic drag, (drag due to shape, frontal area, and surface friction). This is because, for an equal wing area, the average chord (length in the direction of wind travel over the wing) is smaller. Due to the effects of Reynolds number, the value of the section drag coefficient is an inverse logarithmic function of the characteristic length of the surface, which means that, even if two wings of the same area are flying at equal speeds and equal angles of attack, the section drag coefficient is slightly higher on the wing with the smaller chord. However, this variation is very small when compared to the variation in induced drag with changing wingspan.

For example,[8] the section drag coefficient of a NACA 23012 airfoil (at typical lift coefficients) is inversely proportional to chord length to the power 0.129:

of a NACA 23012 airfoil (at typical lift coefficients) is inversely proportional to chord length to the power 0.129:

A 20 percent increase in chord length would decrease the section drag coefficient by 2.38 percent.

- Practicality: low aspect ratios have a greater useful internal volume, since the maximum thickness is greater, which can be used to house the fuel tanks, retractable landing gear and other systems.

- Airfield Size: Airfields, hangars and other ground equipment define a maximum wingspan, which cannot be exceeded, and to generate enough lift at the given wingspan, the aircraft designer has to lower the aspect-ratio and increase the total wing area. This limits the Airbus A380 to 80m wide with an aspect ratio of 7.8, while some Boeing 777 have an aspect ratio of 9.0, influencing flight economy.[9]

Variable aspect ratio

Extending the trailing-edge wing flaps causes a decrease in aspect ratio because extending the flaps increases the wing chord but with no change in wingspan. This decrease in aspect ratio causes an increase in induced drag which is detrimental to the airplane’s performance during takeoff but may be beneficial during landing.

Aircraft which approach or exceed the speed of sound sometimes incorporate variable-sweep wings. This is due to the difference in fluid behavior in the subsonic and transonic/supersonic regimes. In subsonic flow, induced drag is a significant component of total drag, particularly at high angle of attack. However, as the flow becomes transonic and then supersonic, the shock wave first generated along the wing's upper surface causes wave drag on the aircraft, and this drag is proportional to the length of the wing - the longer the wing, the longer the shock wave. Thus a long wing, valuable at low speeds, becomes a detriment at transonic speeds. If the aircraft design can fulfil its mission profiles with the extra weight and complexity of a moveable wing, the swing-wing provides a solution to this problem.

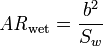

Wetted aspect ratio

The wetted aspect ratio is a good indication of the aerodynamic efficiency of an aircraft. It is a better measure than the aspect ratio. It is defined as:

where  is span and

is span and  is the wetted surface (the entire surface area of the airframe exposed to airflow) of the whole aircraft in contrast to the wing area used for the definition of the aspect ratio.

is the wetted surface (the entire surface area of the airframe exposed to airflow) of the whole aircraft in contrast to the wing area used for the definition of the aspect ratio.

A good example of this is the Boeing B-47 and Avro Vulcan. Both aircraft have very similar performance although they are radically different. The B-47 has a high aspect ratio wing, while the Avro Vulcan is a low aspect ratio blended wing body. They have, however, a very similar wetted aspect ratio.[10]

Aspect ratio of bird wings

High aspect ratio wings abound in nature. Many birds that fly long distances have wings of high aspect ratio, and with tapered or elliptical wingtips. This is particularly noticeable on soaring birds such as albatrosses and eagles. By contrast, hawks of the genus Accipiter such as the Eurasian Sparrowhawk have wings of low aspect ratio (and long tails) for maneuverability.

See also

- Centerboard

- Planform

- Wetted aspect ratio

Notes

- ↑ Kermode, A.C. (1972), Mechanics of Flight, Chapter 3, (p.103, eighth edition), Pitman Publishing Limited, London ISBN 0-273-31623-0

- ↑ Anderson, John D. Jr, Introduction to Flight, Equation 5.26

- ↑ Clancy, L.J., Aerodynamics, sub-section 5.13(f)

- ↑ Clancy, L.J., Aerodynamics, section 5.15

- ↑ Anderson, John D. Jr, Introduction to Flight, section 5.14

- ↑ Clancy, L.J., Aerodynamics, sub-equation 5.8

- ↑ Anderson, John D. Jr, Fundamentals of Aerodynamics, Equation 5.63 (4th edition)

- ↑ Dommasch, D.O., Sherby, S.S., and Connolly, T.F. (1961), Airplane Aerodynamics, page 128, Pitman Publishing Corp. New York

- ↑ Hamilton, Scott. "Updating the A380: the prospect of a neo version and what’s involved" Leehamnews.com, 3 February 2014. Accessed: 21 June 2014. Archived on 8 April 2014.

- ↑ "The Lifting Fuselage Body". Meridian-int-res.com. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

References

- Anderson, John D. Jr, Introduction to Flight, 5th edition, McGraw-Hill. New York, NY. ISBN 0-07-282569-3

- Anderson, John D. Jr, Fundamentals of Aerodynamics, Section 5.3 (4th edition), McGraw-Hill. New York, NY. ISBN 0-07-295046-3

- Clancy, L.J. (1975), Aerodynamics, Pitman Publishing Limited, London ISBN 0-273-01120-0

- John P. Fielding. Introduction to Aircraft Design, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65722-8

- Daniel P. Raymer (1989). Aircraft Design: A Conceptual Approach, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc., Washington, DC. ISBN 0-930403-51-7