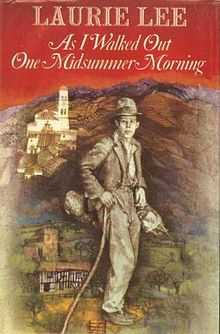

As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning

First edition (UK) | |

| Author | Laurie Lee |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Leonard Rosoman |

| Cover artist | Shirley Thompson |

| Publisher |

André Deutsch (UK) Atheneum Publishers (US) David R. Godine, Publisher (US) |

Publication date | 1969 |

| ISBN | 0-233-96117-8 |

| OCLC | 12104039 |

| 914.6/0481 19 | |

| LC Class | PR6023.E285 Z463 1985 |

| Preceded by | Cider with Rosie |

| Followed by | A Moment of War |

As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning (1969) is a memoir by Laurie Lee, a British poet. It is a sequel to Cider with Rosie which detailed his life in post First World War Gloucestershire. The author leaves the security of his Cotswold village in Gloucestershire to start a new life, at the same time embarking on an epic journey by foot.

It is 1934, and as a young man Lee walks to London from his Cotswolds home. He is to live by playing the violin and by labouring on a London building site. When this work draws to a finish, and having picked up the phrase in Spanish for 'Will you please give me a glass of water?', he decides to go to Spain. He scrapes together a living by playing his violin outside the street cafés, and sleeps at night in his blanket under an open sky or in cheap, rough posadas. For a year he tramps through Spain, from Vigo in the north to the south coast, where he is trapped by the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

Experiencing a Spain ranging from the utterly squalid to the utterly beautiful, Lee creates a story which evocatively captures the spirit and atmosphere of the towns and countryside he passes through in his own distinctive semi-poetic style. He is warmly welcomed by the Spaniards he meets and enjoys a generous hospitality even from the poorest villagers he encounters along the way.

Synopsis

- In England

In 1934 Laurie Lee leaves his home in Slad, Gloucestershire, for London, one hundred miles away. It was a bright Sunday morning in early June, the right time to be leaving home… I was nineteen years old, still soft at the edges, but with a confident belief in good fortune. Never having seen the sea before, he decides he will go by way of Southampton though it will add another hundred miles to his journey. He begins to walk towards the Wiltshire Downs on country roads that

"…still followed their original tracks, drawn by packhorse or lumbering cartwheel, hugging the curve of a valley or yielding to a promontory like the wandering line of a stream. It was not, after all, so very long ago, but no one could make that journey today. Most of the old roads have gone, and the motor car, since then, has begun to cut the landscape to pieces, through which the hunched-up traveller races at gutter height, seeing less than a dog in a ditch."

He visits Southampton and it is here that he first tries his luck at playing his violin in the streets. His apprenticeship proves profitable and with his pockets full of change he decides to move on eastwards. He catches his first glimpse of the sea a mile outside Southampton docks – "It was green, and heaved gently like the skin of a frog, and carried drowsy little ships like flies". Lee makes his way along the south coast, to Chichester, where he is moved on by a policeman after playing Bless This House, to Bognor Regis, and then on again to Worthing, "full of rich, pearl-chokered invalids". From there he turns inland, to the "wide-open Downs", and heads north for London. "I was at that age which feels neither strain nor friction, when the body burns magic fuels, so that it seems to glide in warm air..Even exhaustion when it came had a voluptuous quality..."

As he makes his way to London, he lives on pressed dates and biscuits. "But I was not the only one on the road; I soon noticed there were many others, all trudging northwards in a sombre procession..the majority belonged to that host of unemployed who wandered aimlessly about England at that time." He bumps into a veteran tramp, Alf, "a tramp to his bones", who gives him a very old and battered billy can for brewing up. Eventually, a few mornings later, coming out of a wood near Beaconsfield he sees London at last: " – a long smoky skyline hazed by the morning sun and filling the whole of the eastern horizon. Dry, rusty-red, it lay like a huge flat crust, like ash from some spent volcano, simmering gently in the summer morning and emitting a faint, metallic roar." He decides to take the underground, and finally meets up with his American girlfriend, Cleo, who is the daughter of an American anarchist.

Living with her family in a dilapidated house on Putney Heath, Lee tries to make love to her but she is too full of her father's political ideology. Her father finds him a job as a labourer and he is able to rent a snug little room above a cafe on the Lower Richmond Road. However, he has to move on as his room is taken over by a prostitute, and ends up living with the Flynns, a Cockney family, who welcome him into the family's embrace. He lives in London for almost a year as part of a gang of wheelbarrow pushers, supplying newly mixed cement to the builders. With money to spend, he whiles away his time wandering the London streets, scribbling poetry in his small bedroom and having occasional liaisons with some of the maids from the big houses around Putney Heath. However, once the building nears completion, he knows that his time is up and decides to go to Spain because he knows the phrase in Spanish for "Will you please give me a glass of water?". He pays £4 and takes a ship to Vigo, a port of the north-west coast of Spain.

- In Spain

He lands in Galicia in July 1935. The first half of his journey takes him from Vigo to Madrid. He has a tent, a blanket in which his violin is wrapped, and normally some fruit, bread and cheese to eat along the way. Joining up with a group of three young German musicians, he accompanies them around Vigo and then they split up outside Zamora. Passing through Toro,

he watches a religious procession in which a statue of the Mother of Toro is taken around the town. Lee leaves town the next day, and gives a vivid description of the searing heat of the Spanish sun:

"The violence of the heat seemed to bruise the whole earth and turn its crust into one huge scar. One's blood dried up and all juices vanished; the sun struck upwards, sideways, and down, while the wheat went buckling across the fields like a solid sheet of copper. I kept on walking because there was no shade to hide in, and because it seemed the only way to agitate the air around me...I walked on as though keeping a vow, till I was conscious only of the hot red dust grinding like pepper between my toes."

Valladolid is 'a dark square city hard as its syllables'. It is full of beggars, cripples and beaten-down young Spanish conscripts who have nothing to do in their leisure time. The beggars he remembers, " as something special to Valladolid, something it had nursed to a peak of malformation and horror. One saw them little by day; they seemed to be let out only at night, surreptitiously, like mad relations..Young and old were like emanations of the stifling medievalism of this pious and cloistered city; infected by its stones, like the pock-marked effigies of its churches, and part of one of the more general blasphemies of Spain." The chapter ends on a sour note with his landlord's wife screaming and shouting at her husband because the Borracho has returned home drunk and tried to have sex with their daughter, Elvira.

Making his way to Segovia, Lee's feet become hardened and his Spanish is also improving after almost a month on the road. He spends only a few nights in the town because he is impatient to reach Madrid. He makes the long climb through the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains and is finally given a lift by two young booksellers in their van.

Counting London, Madrid is only the second major city he has seen. Lee feels as though he has "... slipped into Madrid as into the jaws of a lion. It has a lion's breath, too; something fetid and spicy, mixed with straw and the decayed juices of meat. The Gran Via itself has a lion's roar, though inflated like a circus animal's – wide, self-conscious, and somewhat seedy, and lined with buildings like broken teeth." However, he loves the city and is impressed by the pride that its citizens feel. The city lies on a mile high plateau and is the highest capital in Europe, and there is the proverb: 'From the provinces to Madrid – but from Madrid to the sky'. He spends his time drinking wine in the cool taverns during the daytime and playing his violin in the evenings in the older part of the city, the cliffs above the Manzanares where the streets are 'intimate as courtyards, with lamp lit arches smelling of wine and woodsmoke.' He lives in a cheap posada and befriends Concha, the girl who buys his breakfast. She is a husky young widow from Aranjuez and spends her daytimes idling about, waiting for the return of her boyfriend from the Asturias. Sometimes Lee sits out the morning by rubbing fish-oil into her hair. His last night is spent on a late-night drinking binge. He starts at the Calle Echegaray, 'a raffish little lane, half Goya, half Edwardian plush, with cafe-brothels full of painted mirrors, crippled minstrels and lacquered girls' and ends up at the Bar Chicote being chatted up by a young prostitute; however, she leaves him when a minor bullfighter arrives with his court of gypsies. He returns drunk to his posada and is helped into bed by Concha, who makes the sign of the cross before she joins him.

By August 1935 Lee reaches Toledo, where he has a meeting with the South African poet Roy Campbell and his family, whom he comes across while playing his violin in the open-air cafés in the Plaza de Zocodover:

"It was the poet's saint's-day, and the party had dressed in his honour and were drinking his health in fizzy pop. Campbell himself drunk wine in long shuddering gasps, and suggested I do the same. I was more than satisfied by this encounter, which had come so unexpectedly out of the evening, pleased to have arrived on foot in this foreign city in time to be elected to this poet's table."

The Campbells invite him to stay in their house, which lies close to the cathedral. Campbell spends the daytime sleeping but comes to life in the evenings:

"During most of the daylight hours Roy lay low and slept, appearing at nightfall like some ruffled sea-bird, leaning against a pillar with his arms stretched wide as though drying his salt-wet wings. One saw him gathering his wits in great gulps of breath, after which he would be ready for anything."

After a final day of drinking with the poet, Lee makes his departure the next day and is accompanied by the poet as far as the bridge by which he would cross the gorge of the Tagus. By the end of September he has reached the sea, having passed through Valdepeñas, Cordova, and Seville to reach Cádiz – " at that time..nothing but a rotten hulk on the edge of a disease-ridden tropic sea; its people dismayed, half-mad, consoled only by vicious humour, prisoners rather than citizens." He looks back on his last month on the road through September. He describes Valdepeñas as 'a surprise: a small graceful town surrounded by rich vineyards and prosperous villas – a pocket of good fortune which seemed to produce without effort some of the most genial wines in Spain.' It had been a very friendly town and whilst busking one evening three young men had invited him to go with them to a brothel. Lee played his violin and watched the customers coming and going as he was plied with wine by the old grandfather who ran the place. There were four girls, two sisters and two cousins, and the whole establishment had possessed a very intimate atmosphere, 'a casual atmosphere of neighbourly visiting, hosted by these vague and sleepy girls; subdued talk, a little music, an air of domestic eroticism, with unhurried comings and goings.'

Then he came to the Sierra Morena mountains, "one more of those east-west ramparts which go ranging across Spain and divide its people into separate races." South of the Sierra, he met:

"... a new kind of heat, brutal and hard, carrying the smell of another continent. As I came down the mountain this heat piled up, pushing against me with blasts of sand, so that I walked half-blind, my tongue dry as a carob bean, obsessed once again by thirst. These were ominous days of nerve-bending sirocco, with peasants wrapped up to the eyes,..but far down in the valley, running in slow green coils, I could see at last the tree-lined Guadalquivir.. "

Entering the province of Andalusia through fields of ripening melons, he saw the first signs of the southern people: men in tall Cordobese hats, blue shirts, scarlet waistbands, and girls with smouldering Arab faces. Instead of taking the road south to Granada, he decided to turn west and follow the Guadalquivir, adding several months to his journey, and taking him to the sea in a roundabout way. He lives in Seville, – " dazzling – a creamy crustation of flower-banked houses fanning out from each bank of the river...[yet]..no paradise, even so. There was the customary squalor behind it – children and beggars sleeping out in the gutters.." He lives on fruit and dried fish, and sleeps at night in a yard in Triana a ramshackle barrio on the north bank of the river, which has 'a seedy vigour, full of tile-makers and free-range poultry, of medieval stables, bursting with panniered donkeys, squabbling wives and cooking pots.' Whilst he spends his evening trying to get cool on the flat roof of the Café Faro, eating chips and gazing at the river, he hears the first mention of the upcoming war:

"Until now I'd accepted this country without question, as though visiting a half-crazed family. I'd seen the fat bug-eyed rich gazing glassily from their clubs, men scrabbling for scraps in the market, dainty upper-class virgins riding to church in carriages, beggar-women giving birth in doorways. Naïve and uncritical, I'd thought it part of the scene, not asking whether it was right or wrong ... A young sailor approached me with a "Hallo, Johnny" ... "I don't know who you are", he said, "but if you want to see blood, stick around – you're going to see plenty."

Disliking Cadiz – 'life in Cadiz was too acrid to hold me' – Lee turns eastwards, heading along the bare coastal shelf of Andalusia. He hears talk of war – in Abyssinia, " meaningless to me, who hadn't seen a newspaper for almost three months." He arrives at Tarifa, the southernmost point of Europe, 'skulking behind its Arab walls' and moves on into the country, making another stop over in Algeciras, a town which he very much likes for its aura of illicitness:

"It was a scruffy little town built round an open drain and smelling of fruit skins and rotten fish. There were a few brawling bars and modest brothels; otherwise the chief activity was smuggling ... it seemed to be a town entirely free of malice, and even the worst of its crooks were so untrained in malevolence that no one was expected to take them seriously..I remember the fishing boats at dawn bringing in tunny from the Azores, the markets full of melons and butterflies, the international freaks drinking themselves into multi-lingual stupors, the sly yachts running gold to Tangier..."

Half in love with Algeciras, he felt he "could have stayed on there indefinitely" but decides nevertheless to stick to his plan to follow the coast round Spain, and sets off for Málaga. He makes a stop over in Gibraltar, " more like Torquay", is questioned by the police, and told to report to their station at night. 'Leaving Gibraltar was like escaping from an elder brother in charge of an open jail.' It takes him five days to walk to Malaga, following a coastline smelling of hot seaweed, thyme and shellfish, and occasionally passing through cork-woods smoking with the camp fires of gypsies. At night he finds a field and wraps himself up in his blanket. "The road to Malaga followed a beautiful but exhausted shore, seemingly forgotten by the world. I remember the names – San Pedro, Estepona, Marbella, and Fuengirola..They were salt-fish villages, thin-ribbed..At that time one could have bought the whole coast for a shilling. Not Emperors could buy it now."

In Málaga, he stays in a posada (an inn), sharing the courtyard with a dozen families who are mostly mountain people selling their beautiful hand-woven Alpujarras blankets and cloth in the city. The young girls are some of the most graceful he has ever seen, 'light-footed and nimble as deer, with long floating arms and articulate bodies which turned every movement into a ritual dance.' Malaga was full of foreigners, a snug expatriate colony, and everyone is very chummy apart from the English debs with 'that particular rainswept grey of their English eyes, only noticeable when abroad.'

It is the young Germans who outnumber the rest of the colony, amongst them – " Walter and Shulamith, two Jewish refugees, who had walked from Berlin carrying their one-year-old child. I see them today as part of the shadow of the times.." Disaster seems to arrive during his last days in Malaga when his violin breaks. After his new line of work, acting as a guide to British tourists, is curtailed by local guides, he is then fortunate to meet a young German who gives him a violin for free . It had belonged to his girlfriend and she'd run off with a Swede.

Winter 1935. Lee decides to hole-up in Almuñécar, sixty miles east of Malaga:

"It was a tumbling little village, built on an outcrop of rock in the midst of a pebbly delta, backed by a bandsaw of mountains and fronted by a grey strip of sand which some hoped would be an attraction for tourists ... Almuñécar itself, built of stone steps from the delta, was grey, almost gloomily Welsh. The streets were steep, roughly paved, and crossed by crude little arches, while the square was like a cobbled farmyard...past glories were eroding fast."

He manages to get work in a hotel run by a Swiss, Herr Brandt, who has unfortunately arrived there twenty years too early. The whole area is very poor, with the peasants just managing to scrape a living from the sugar cane grown in the delta, and from the sea:

"But the land was rich compared with the sea, which nourished only a scattering of poor sardines. As there were no boats or equipment for deep-sea fishing, the village was chained to the offshore wastes, shallow, denuded, too desperately fished to provide anything but constant reproaches...The only people with jobs seemed to be the village girls, most of them in service to the richer families, where for a bed in a cupboard and a couple of pounds a year they were expected to run the whole house and keep the men from the brothels."

With nothing much to do in their spare time, Lee and his friend Manolo, the hotel's waiter, drink in the local bar alongside the other villagers, drinking rough brandy mixed with boiling water and eating morunos – little dishes of hot pig flesh stewed in sauce. Manolo is the leader of a group of fishermen and labourers and they sit in a room at the back discussing the expected revolution – " a world to come – a world without church or government or army, where each man alone would be his private government. "

February 1936. The Socialists win the election and a Popular Front, People's Government, arrives. As Spring appears a whiff of change is in the air, with a loosening of social and sexual behaviour and manners:

"Books and films appeared, unmutilated by Church or State, bringing to the peasants of the coast, for the first time in generations, a keen breath of the outside world. For a while there was a complete lifting of censorship, even in newspapers and magazines. But most of all it was the air of carnality, the brief clearing away of taboos, which seemed to possess the village – a sudden frank, even frantic, pursuit of lust, bred from a sense of impending peril."

The villagers, in an act of revolt, burn down the church but then do a volte-face when Feast Day arrives and the images of Christ and the Virgin are brought out into the open, loaded as usual on the fishermen's backs. In the middle of May, there is a strike and the peasants come in from the countryside to lend their support as the village splits down the middle between 'Fascists' and 'Communists'. " The local flag of revolution was the Republican flag, the flag of the elected government. The peasants strung it like a banner across the Town Hall balcony and painted their allegiance beneath it in red ." There is also hope in the air that the working class will see an improvement in their terrible living conditions:

"Spain was a wasted country of neglected land – much of it held by a handful of men, some of whose vast estates had scarcely been reduced or reshuffled since the days of the Roman Empire..Now it was hoped that there might be some lifting of this intolerable darkness, some freedom to read and write and talk. Men hoped that their wives might be freed of the triple trivialities of the Church – credulity, guilt and confession; that their sons might be craftsmen rather than serfs, their daughters citizens rather than domestic whores, and that they might hear the children in the evening coming home from the fresh-built schools to astonish them with new facts of learning."

The middle of July 1936. War now breaks out. There had been anti-Government uprisings in the garrisons of Spanish Morocco – at Melilla, Tetuan and Larache. General Francisco Franco, the butcher of the Asturias, had flown from the Canaries to lead the rebels. With the disappearance of the police, " the village was on its own: Government supporters facing the enemy within." Manolo and El Gato (the leader of one of the new-formed unions) start to organise some kind of militia. Granada is held by the rebels, and so is Almunecar's neighbour Altofaro, ten miles down the coast. Almuñécar is mistakenly fired on by a Government warship that thinks it is shelling rebel-held Altofaro. Lee hears on Radio Sevilla Queipo de Llano exulting in the fall of the city. The rebel general is drunk and slurs his phrases. "Christ had triumphed, he ranted, through God's army in Spain, of which Generalissimo Franco was the sainted leader...'Viva España! Viva la Virgen!' ". Finally, a British destroyer from Gibraltar arrives to pick up any British subjects who might be marooned on the coast. Lee and the English novelist from whom he is renting a room are taken on board and he takes his last look at Almuñécar and Spain as they grow smaller in the distance.

"All I'd known in that country – or had felt without knowing it – seemed to come upon me then; lost now, and too late to have any meaning, my twelve months' journey gone. Spain drifted away from me, thunder-bright on the horizon, and I left it there beneath its copper clouds."

The Epilogue describes Lee's return to his family home in Gloucestershire and his desire to help his comrades in Spain. He is held back by a liaison with a wealthy lover but finally decides to make his way through France to cross the Pyrenees into Spain. After a desperate climb starting from Ceret in the foothills, in which he gets caught in a snow storm, he ends up in another French village. Here he is helped by a peasant, after another tortuous climb through the thick snow, to cross the border once more into Spain.

Title

An insight into the origin of the title of the book is found in the second episode the BBC Four documentary series Travellers' Century presented by Benedict Allen. In the episode, which looks at As I Walked Out..., a friend of Lee reveals that the title of the book comes from a Gloucestershire folk song. The traditional song 'The Banks of Sweet Primroses' starts with the line "As I walked out one mid-summer morning'.[1]

References

- ↑ 'The Banks of Sweet Primroses' lyrics on Folkinfo.org

- As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, Penguin Books (1971) ISBN 0140033181

External links

- "BBC Four – Audio Interviews – Laurie Lee". BBC. 21 September 1985. Retrieved 22 May 2007.

- "Laurie Lee". Penguin Group (Canada). Retrieved 22 May 2007.

- Rick Price (3 December 2003). "Reading Room: Book Reviews: As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning by Laurie Lee". www.ExperiencePlus.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2007.

- "Books and Writers: Laurie Lee (1914–1997)". www.kirjasto.sci.fi. Archived from the original on 20 April 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2007.