Artinian ring

In abstract algebra, an Artinian ring is a ring that satisfies the descending chain condition on ideals. They are also called Artin rings and are named after Emil Artin, who first discovered that the descending chain condition for ideals simultaneously generalizes finite rings and rings that are finite-dimensional vector spaces over fields. The definition of Artinian rings may be restated by interchanging the descending chain condition with an equivalent notion: the minimum condition.

A ring is left Artinian if it satisfies the descending chain condition on left ideals, right Artinian if it satisfies the descending chain condition on right ideals, and Artinian or two-sided Artinian if it is both left and right Artinian. For commutative rings the left and right definitions coincide, but in general they are distinct from each other.

The Artin–Wedderburn theorem characterizes all simple Artinian rings as the matrix rings over a division ring. This implies that a simple ring is left Artinian if and only if it is right Artinian.

Although the descending chain condition appears dual to the ascending chain condition, in rings it is in fact the stronger condition. Specifically, a consequence of the Akizuki–Hopkins–Levitzki theorem is that a left (right) Artinian ring is automatically a left (right) Noetherian ring. This is not true for general modules, that is, an Artinian module need not be a Noetherian module.

Examples

- An integral domain is Artinian if and only if it is a field.

- A ring with finitely many, say left, ideals is left Artinian. In particular, a finite ring (e.g.,

) is left and right Artinian.

) is left and right Artinian. - Let k be a field. Then

![k[t]/(t^n)](../I/m/ccc0d2f3c8250989e27d371600dc2b02.png) is Artinian for every positive integer n.

is Artinian for every positive integer n. - If I is a nonzero ideal of a Dedekind domain A, then

is a principal Artinian ring.[1]

is a principal Artinian ring.[1] - For each

, the full matrix ring

, the full matrix ring  over a left Artinian (resp. left Noetherian) ring R is left Artinian (resp. left Noetherian).[2]

over a left Artinian (resp. left Noetherian) ring R is left Artinian (resp. left Noetherian).[2]

The ring of integers  is a Noetherian ring but is not Artinian.

is a Noetherian ring but is not Artinian.

Modules over Artinian rings

Let M be a left module over a left Artinian ring. Then the following are equivalent (Hopkins' theorem): (i) M is finitely generated, (ii) M has finite length (i.e., has composition series), (iii) M is Noetherian, (iv) M is Artinian.[3]

Commutative Artinian rings

Let A be a commutative Noetherian ring with unity. Then the following are equivalent.

- A is Artinian.

- A is a finite product of commutative Artinian local rings.[4]

- A / nil(A) is a semisimple ring, where nil(A) is the nilradical of A.[5]

- Every finitely generated module over A has finite length. (see above)

- A has Krull dimension zero.[6] (In particular, the nilradical is the Jacobson radical since prime ideals are maximal.)

is finite and discrete.

is finite and discrete. is discrete.[7]

is discrete.[7]

Let k be a field and A finitely generated k-algebra. Then A is Artinian if and only if A is finitely generated as k-module.

An Artinian local ring is complete. A quotient and localization of an Artinian ring is Artinian.

Simple Artinian ring

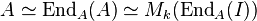

A simple Artinian ring A is a matrix ring over a division ring. Indeed,[8] let I be a minimal (nonzero) right ideal of A. Then, since  is a two-sided ideal,

is a two-sided ideal,  since A is simple. Thus, we can choose

since A is simple. Thus, we can choose  so that

so that  . Assume k is minimal with respect that property. Consider the map of right A-modules:

. Assume k is minimal with respect that property. Consider the map of right A-modules:

It is surjective. If it is not injective, then, say,  with nonzero

with nonzero  . Then, by the minimality of I, we have:

. Then, by the minimality of I, we have:  . It follows:

. It follows:

,

,

which contradicts the minimality of k. Hence,  and thus

and thus  .

.

See also

- Artin algebra

- Artinian ideal

- Serial module

- Semiperfect ring

- Noetherian ring

Notes

- ↑ Theorem 459 of http://math.uga.edu/~pete/integral.pdf

- ↑ Cohn 2003, 5.2 Exercise 11

- ↑ Bourbaki, VIII, pg 7

- ↑ Atiyah & Macdonald 1969, Theorems 8.7

- ↑ Sketch: In commutative rings, nil(A) is contained in the Jacobson radical of A. Since A/nil(A) is semisimple, nil(A) is actually equal to the Jacobson radical of A. By Levitzky's theorem, nil(A) is a nilpotent ideal. These last two facts show that A is a semiprimary ring, and by the Hopkins–Levitzki theorem A is Artinian.

- ↑ Atiyah & Macdonald 1969, Theorems 8.5

- ↑ Atiyah & Macdonald 1969, Ch. 8, Exercise 2.

- ↑ Milnor, John Willard (1971), Introduction to algebraic K-theory, Annals of Mathematics Studies 72, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, p. 144, MR 0349811, Zbl 0237.18005

References

- Auslander, Maurice; Reiten, Idun; Smalø, Sverre O. (1995), Representation theory of Artin algebras, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics 36, Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511623608, ISBN 978-0-521-41134-9, MR 1314422

- Bourbaki, Algèbre

- Charles Hopkins. Rings with minimal condition for left ideals. Ann. of Math. (2) 40, (1939). 712–730.

- Atiyah, Michael Francis; Macdonald, I.G. (1969), Introduction to Commutative Algebra, Westview Press, ISBN 978-0-201-40751-8

- Cohn, Paul Moritz (2003). Basic algebra: groups, rings, and fields. Springer. ISBN 978-1-85233-587-8.