Art gallery problem

The art gallery problem or museum problem is a well-studied visibility problem in computational geometry. It originates from a real-world problem of guarding an art gallery with the minimum number of guards who together can observe the whole gallery. In the computational geometry version of the problem the layout of the art gallery is represented by a simple polygon and each guard is represented by a point in the polygon. A set  of points is said to guard a polygon if, for every point

of points is said to guard a polygon if, for every point  in the polygon, there is some

in the polygon, there is some  such that the line segment between

such that the line segment between  and

and  does not leave the polygon.

does not leave the polygon.

Two dimensions

There are numerous variations of the original problem that are also referred to as the art gallery problem. In some versions guards are restricted to the perimeter, or even to the vertices of the polygon. Some versions require only the perimeter or a subset of the perimeter to be guarded.

Solving the version in which guards must be placed on vertices and only vertices need to be guarded is equivalent to solving the dominating set problem on the visibility graph of the polygon.

Chvátal's art gallery theorem

Chvátal's art gallery theorem, named after Václav Chvátal, gives an upper bound on the minimal number of guards. It states that  guards are always sufficient and sometimes necessary to guard a simple polygon with

guards are always sufficient and sometimes necessary to guard a simple polygon with  vertices.

vertices.

The question about how many vertices/watchmen/guards were needed was posed to Chvátal by Victor Klee in 1973.[1] Chvátal proved it shortly thereafter.[2] Chvátal's proof was later simplified by Steve Fisk, via a 3-coloring argument.[3]

Fisk's short proof

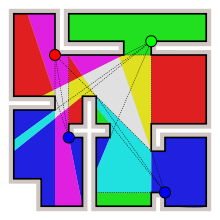

Fisk (1978) proves the art gallery theorem as follows.

First, the polygon is triangulated (without adding extra vertices). The vertices of the polygon are then 3-colored in such a way that every triangle has all three colors. To find a 3-coloring, it is helpful to observe that the dual graph to the triangulation (the undirected graph having one vertex per triangle and one edge per pair of adjacent triangles) is a tree, for any cycle in the dual graph would form the boundary of a hole in the polygon, contrary to the assumption that it has no holes. Whenever there is more than one triangle, the dual graph (like any tree) must have a vertex with only one neighbor, corresponding to a triangle that is adjacent to other triangles along only one of its sides. The simpler polygon formed by removing this triangle has a 3-coloring by mathematical induction, and this coloring is easily extended to the one additional vertex of the removed triangle.

Once a 3-coloring is found, the vertices with any one color form a valid guard set, because every triangle of the polygon is guarded by its vertex with that color. Since the three colors partition the n vertices of the polygon, the color with the fewest vertices forms a valid guard set with at most  guards.

guards.

Generalizations

Chvátal's upper bound remains valid if the restriction to guards at corners is loosened to guards at any point not exterior to the polygon.

There are a number of other generalizations and specializations of the original art-gallery theorem.[4] For instance, for orthogonal polygons, those whose edges/walls meet at right angles, only  guards are needed. There are at least three distinct proofs of this result, none of them simple: by Kahn, Klawe, and Kleitman; by Lubiw; and by Sack and Toussaint.[5]

guards are needed. There are at least three distinct proofs of this result, none of them simple: by Kahn, Klawe, and Kleitman; by Lubiw; and by Sack and Toussaint.[5]

A related problem asks for the number of guards to cover the exterior of an arbitrary polygon (the "Fortress Problem"):  are sometimes necessary and always sufficient. In other words, the infinite exterior is more challenging to cover than the finite interior.[6]

are sometimes necessary and always sufficient. In other words, the infinite exterior is more challenging to cover than the finite interior.[6]

Computational complexity

In decision problem versions of the art gallery problem, one is given as input both a polygon and a number k, and must determine whether the polygon can be guarded with k or fewer guards. This problem and all of its standard variations (such as restricting the guard locations to vertices or edges of the polygon) are NP-hard.[7] Regarding approximation algorithms for the minimum number of guards, Eidenbenz, Stamm & Widmayer (2001) proved the problem to be APX-hard, implying that it is unlikely that any approximation ratio better than some fixed constant can be achieved by a polynomial time approximation algorithm. However, a constant approximation ratio is not known. Instead, a logarithmic approximation may be achieved for the minimum number of vertex guards by reducing the problem to a set cover problem.[8] As Valtr (1998) showed, the set system derived from an art gallery problem has bounded VC dimension, allowing the application of set cover algorithms based on ε-nets whose approximation ratio is the logarithm of the optimal number of guards rather than of the number of polygon vertices.[9] For unrestricted guards, the infinite number of potential guard positions makes the problem even more difficult.[10]

However, efficient algorithms are known for finding a set of at most  vertex guards, matching Chvátal's upper bound.

David Avis and Godfried Toussaint (1981) proved that a placement for these guards may be computed in O(n log n) time in the worst case, via a divide and conquer algorithm.

Kooshesh & Moret (1992) gave a linear time algorithm by using Fisk's short proof and Bernard Chazelle's linear time plane triangulation algorithm.

vertex guards, matching Chvátal's upper bound.

David Avis and Godfried Toussaint (1981) proved that a placement for these guards may be computed in O(n log n) time in the worst case, via a divide and conquer algorithm.

Kooshesh & Moret (1992) gave a linear time algorithm by using Fisk's short proof and Bernard Chazelle's linear time plane triangulation algorithm.

An exact algorithm was proposed by Couto, de Rezende & de Souza (2011) for vertex guards. The authors conducted extensive computational experiments with several classes of polygons showing that optimal solutions can be found in relatively small computation times even for instances associated to thousands of vertices. The input data and the optimal solutions for these instances are available for download.[11]

Three dimensions

If a museum is represented in three dimensions as a polyhedron, then putting a guard at each vertex will not ensure that all of the museum is under observation. Although all of the surface of the polyhedron would be surveyed, for some polyhedra there are points in the interior which might not be under surveillance.[12]

Notes

- ↑ O'Rourke (1987), p. 1.

- ↑ Chvátal (1975).

- ↑ Fisk (1978).

- ↑ Shermer (1992).

- ↑ O'Rourke (1987), pp. 31–80; Kahn, Klawe & Kleitman (1983); Lubiw (1985); Sack & Toussaint (1988).

- ↑ O'Rourke (1987), pp. 146–154.

- ↑ O'Rourke (1987), pp. 239–242; Aggarwal (1984); Lee & Lin (1986).

- ↑ Ghosh (1987).

- ↑ Brönnimann & Goodrich (1995).

- ↑ Deshpande et al. (2007)

- ↑ Couto, de Rezende & de Souza (2011).

- ↑ O'Rourke (1987), p. 255.

See also

References

- Aggarwal, A. (1984), The art gallery theorem: Its variations, applications, and algorithmic aspects, Ph.D. thesis, Johns Hopkins University.

- Avis, D.; Toussaint, G. T. (1981), "An efficient algorithm for decomposing a polygon into star-shaped polygons", Pattern Recognition 13 (6): 395–398, doi:10.1016/0031-3203(81)90002-9.

- Brönnimann, H.; Goodrich, M. T. (1995), "Almost optimal set covers in finite VC-dimension", Discrete and Computational Geometry 14 (1): 463–479, doi:10.1007/BF02570718.

- Chvátal, V. (1975), "A combinatorial theorem in plane geometry", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 18: 39–41, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(75)90061-1.

- Couto, M.; de Rezende, P.; de Souza, C. (2011), "An exact algorithm for minimizing vertex guards on art galleries", International Transactions in Operational Research: no–no, doi:10.1111/j.1475-3995.2011.00804.x.

- Couto, M.; de Rezende, P.; de Souza, C. (2011), Benchmark instances for the art gallery problem with vertex guards.

- Deshpande, Ajay; Kim, Taejung; Demaine, Erik D.; Sarma, Sanjay E. (2007), "A Pseudopolynomial Time O(logn)-Approximation Algorithm for Art Gallery Problems", Proc. Worksh. Algorithms and Data Structures, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4619, Springer-Verlag, pp. 163–174, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-73951-7_15, ISBN 978-3-540-73948-7.

- Eidenbenz, S.; Stamm, C.; Widmayer, P. (2001), "Inapproximability results for guarding polygons and terrains", Algorithmica 31 (1): 79–113, doi:10.1007/s00453-001-0040-8.

- Fisk, S. (1978), "A short proof of Chvátal's watchman theorem", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 24 (3): 374, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(78)90059-X.

- Ghosh, S. K. (1987), "Approximation algorithms for art gallery problems", Proc. Canadian Information Processing Society Congress, pp. 429–434.

- Kahn, J.; Klawe, M.; Kleitman, D. (1983), "Traditional galleries require fewer watchmen", SIAM J. Alg. Disc. Meth. 4 (2): 194–206, doi:10.1137/0604020.

- Kooshesh, A. A.; Moret, B. M. E. (1992), "Three-coloring the vertices of a triangulated simple polygon", Pattern Recognition 25 (4): 443, doi:10.1016/0031-3203(92)90093-X.

- Lee, D. T.; Lin, A. K. (1986), "Computational complexity of art gallery problems", IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 32 (2): 276–282, doi:10.1109/TIT.1986.1057165.

- Lubiw, A. (1985), "Decomposing polygonal regions into convex quadrilaterals", Proc. 1st ACM Symposium on Computational Geometry, pp. 97–106, doi:10.1145/323233.323247, ISBN 0-89791-163-6.

- O'Rourke, Joseph (1987), Art Gallery Theorems and Algorithms, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-503965-3.

- Sack, J. R.; Toussaint, G. T. (1988), "Guard placement in rectilinear polygons", in Toussaint, G. T., Computational Morphology, North-Holland, pp. 153–176.

- Shermer, Thomas (1992), "Recent Results in Art Galleries", Proceedings of the IEEE 80 (9): 1384–1399, doi:10.1109/5.163407.

- Valtr, P. (1998), "Guarding galleries where no point sees a small area", Israel J. Math. 104 (1): 1–16, doi:10.1007/BF02897056.