Ars nova

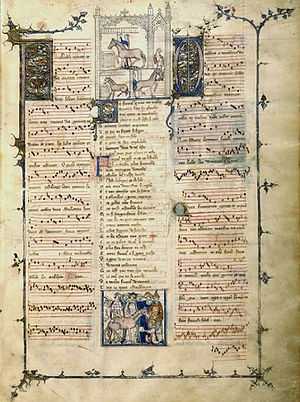

Ars nova refers to a musical style which flourished in France and the Burgundian Low Countries in the Late Middle Ages: more particularly, in the period between the preparation of the Roman de Fauvel (1310–1314) and the death of the composer Guillaume de Machaut in 1377 (whose poems were a large inspiration for Johannes Ciconia). Sometimes the term is used more generally to refer to all European polyphonic music of the 14th century, thereby including such figures as Francesco Landini, who was working in Italy. Occasionally the term "Italian ars nova" is used to denote the music of Landini and his compatriots (see Music of the Trecento for the concurrent musical movement in Italy). In ancient and medieval Latin the term "ars nova" does not mean "new art", but rather "new technique",[2] and was first used in two contemporaneous manuscripts, titled Ars novae musicae (New Technique of Music) (c. 1320) by Johannes de Muris, and Ars nova notandi (A New Technique of Writing [Music]) attributed to Philippe de Vitry (c. 1322). However, the term was only first used to describe an historical era by Johannes Wolf in 1904.[3]

The term "ars nova" is generally used in conjunction with another term, "ars antiqua", which refers to the music of the immediately preceding age, usually extending back to take in the period of Notre Dame polyphony (therefore covering the period from about 1170 to 1320). Roughly, then, the "ars antiqua" is the music of the thirteenth century, and the "ars nova" the music of the fourteenth; many music histories use the terms in this more general sense.

Controversial in the Roman Catholic Church, the music was starkly rejected by Pope John XXII, but embraced by Pope Clement VI. The monophonic chant, already harmonized with simple organum, was becoming altered, fragmented, and hidden beneath secular tunes. The lyrics of love poems might be sung above sacred texts, or the sacred text might be placed within a familiar secular melody. It was not merely polyphony that offended the medieval ears, but the notion of secular music merging with the sacred and making its way into the liturgy.

Ars nova versus Ars antiqua

Stylistically, the music of the ars nova differed from the preceding era in several ways. Developments in notation allowed notes to be written with greater independence of rhythm, shunning the limitations of the rhythmic modes which prevailed in the thirteenth century; secular music acquired much of the polyphonic sophistication previously found only in sacred music; and new techniques and forms, such as isorhythm and the isorhythmic motet, became prevalent. The overall aesthetic effect of these changes was to create music of greater expressiveness and variety than had been the case in the thirteenth century.[4] Indeed the sudden historical change which occurred, with its startling new degree of musical expressiveness, can be likened to the introduction of perspective in painting, and it is useful to consider that the changes to the musical art in the period of the ars nova were contemporary with the great early Renaissance revolutions in painting and literature.

The most famous practitioner of the new musical style was Guillaume de Machaut, who also had a distinguished career as a canon at Reims Cathedral and as a poet. The ars-nova style is evident in his considerable body of motets, lais, virelais, rondeaux, and ballades.

Towards the end of the fourteenth century a new stylistic school of composers and poets centered on Avignon in southern France developed; the highly mannered style of this period is often called the ars subtilior, though some scholars choose to consider it a late development of the ars nova rather than breaking it out as a separate school. This strange but interesting repertory of music, limited in geographical distribution (southern France, Aragon and later Cyprus), and clearly intended for performance by specialists for an audience of connoisseurs, is like an endnote to the entire Middle Ages.

Discography

- Chants du xivème siècle. Mora Vocis Ensemble. France: Mandala, 1999. CD recording MAN 4946.

- Denkmäler alter Musik aus dem Codex Reina (14./15. Jh.). Syntagma Musicum (Kees Otten, dir.). Das Alte Werk. [N.p.]: Telefunken, 1979. LP recording 6.42357.

- Domna. Esther Lamandier, voice, harp, and portative organ. Paris: Alienor, 1987. CD recording AL 1019.

- La fontaine amoureuse: Poetry and Music of Guillaume de Machaut. Music for a While, with Tom Klunis, narrator. Berkeley: 1750 Arch Records, 1977. LP recording 1773.

- Guillaume de Machaut. Je, Guillaumes Dessus Nommez. Ensemble Gilles Binchois (Dominique Vellard, dir.). [N.p.]: Cantus, 2003. CD recording 9804.

- Guillaume de Machaut. La Messe de Nostre Dame und Motetten. James Bowman, Tom Sutcliffe, countertenors; Capella Antiqua München (Konrad Ruhland, dir.). Das Alte Werk. Hamburg: Telefunken, 1970. LP recording 6.41125 AS.

- Guillaume de Machaut. La messe de Nostre Dame; Le voir dit. Oxford Camerata (Jeremy Summerly, dir.). Hong Kong: Naxos, 2004. CD recording 8553833.

- Guillaume de Machaut. Messe de Notre Dame. Ensemble Organum (Marcel Pérès, dir.). Arles: Harmonia Mundi, 1997. CD recording 901590.

- Guillaume de Machaut. Messe de Notre Dame; Le lai de la fonteinne; Ma fin est mon commencement. Hilliard Ensemble (Paul Hillier, dir.). London: Hyperion, 1989.

- Guillaume de Machaut. Motets. Hilliard Ensemble. Munich: ECM Records, 2004.

- Philippe De Vitry and the Ars Nova—Motets. Orlando Consort. Wotton-Under-Edge, Glos., England: Amon Ra, 1990. CD recording CD-SAR 49.

- Philippe de Vitry. Motets & Chansons. Sequentia (Benjamin Bagby and Barbara Thornton, dir.) Freiburg: Deutsche Harmonia Mundi, 1991. CD recording 77095-2-RC.

- Roman de Fauvel. Jean Bollery (speaker), Studio der Frühen Musik (Thomas Binkley, dir.). Reflexe: Stationen europäischer Musik. Cologne: EMI, 1972. LP recording 1C 063-30 103.

- Le roman de Fauvel. Anne Azéma (soprano, narration), Dominique Visse (countertenor, narration), Boston Camerata and Ensemble Project Ars Nova (Joel Cohen, dir.). France: Erato, 1995. CD recording 4509-96392-2.

- The Service of Venus and Mars: Music for the Knights of the Garter, 1340–1440. Gothic Voices (Christopher Page, dir.). London: Hyperion, 1987. CD recording CDA 66238.

- The Spirit of England and France I: Music of the Late Middle Ages for Court and Church. Gothic Voices (Christopher Page, dir.). London: Hyperion Records, 1994. CD recording CDA66739.

- The Study of Love: French Songs and Motets of the 14th Century. Gothic Voices (Christopher Page, dir.). London: Hyperion Records, 1992. CD recording CDA66619.

Notes

References

- Earp, Lawrence (1995). "Ars nova". In Medieval France: An Encyclopedia, edited by William W. Kibler, Grover A. Zinn, Lawrence Earp, and John Bell Henneman, Jr., 72–73. Garland Reference Library of the Humanities 932; Garland Encyclopedias of the Middle Ages 2. New York: Garland Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8240-4444-2.

- Fallows, David. (2001). "Ars nova". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Schrade, Leo (1956). "Philippe de Vitry: Some New Discoveries". The Musical Quarterly 42, no. 3 (July): 330–54.

Further reading

- (1980). "Ars nova". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by Stanley Sadie. 20 vols. London: Macmillan Publishers Ltd. ISBN 1-56159-174-2.

- Fuller, Sarah (1985–86). "A Phantom Treatise of the Fourteenth Century? The Ars Nova". The Journal of Musicology 4, no. 1 (Winter): 23–50.

- Gleason, Harold, and Warren Becker (1986). Music in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Music Literature Outlines Series 1. Bloomington, Indiana: Frangipani Press. ISBN 0-89917-034-X.

- Hoppin, Richard H. (1978). Medieval Music. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-09090-6.

- Leech-Wilkinson, Daniel (1990). "Ars Antiqua—Ars Nova—Ars Subtilior". In Antiquity and the Middle Ages: From Ancient Greece to the 15th Century, edited by James McKinnon, 218–40. Man and Music. London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0-333-51040-2 (cased); ISBN 0-333-53004-7 (pbk).

- Snellings, Dirk (2003). "Ars Nova and Trecento Music in 14th Century Europe" (retrieved on 2008-06-14), translated by Stratton Bull, 12. CD Booklet CAPI 2003.

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||