Armenians in Syria

| ||||||||||

| Total population | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80,000 (prior to the civil war)[1] | ||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||

|

Aleppo, Qamishli, Damascus, Latakia Kessab and Yakubiyah (two Armenian-inhabited small towns) | ||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||

| Armenian, Arabic | ||||||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Armenian Apostolic, Armenian Catholic, Armenian Evangelical | ||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||

| Armenian, Hamshenis, Cherkesogai groups | ||||||||||

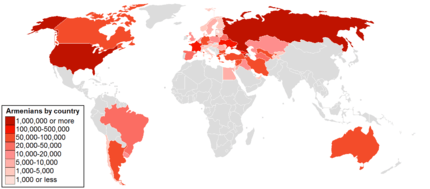

The Armenians in Syria are Syrian citizens of either full or partial Armenian descent. Syria and the surrounding areas have often served as a refuge for Armenians who fled from wars and persecutions such as the Armenian Genocide. According to the Ministry of Diaspora of the Republic of Armenia, the estimated number of Armenians in Syria is 100,000, with more than 60,000 of them are centralized in Aleppo.[2] However, as of the end of 2013, an estimated number of 9,000 of Syria's Armenian community have arrived in Armenia since the break out of the Syrian Civil War.[3] Another 8,000 left for Lebanon, with fewer numbers have moved to Europe and the United States.[4]

The small Syrian towns of Kessab and Yakubiyah -located near the Turkish border- have Armenian majority.[5]

History

Early history

During the ancient times, there was a small Armenian presence in northern Syria. Under Tigranes the Great, Armenians invaded Syria and the city of Antioch was chosen as one of the four capitals of the short-lived Armenian Empire.

In 301, Christianity became the official religion of Armenia through the efforts of Saint Gregory the Illuminator. Armenian merchants and pilgrims started to visit the earliest Christian centres of Greater Syria including Antioch, Edessa, Nisibis and Jerusalem. Close relations were established between the Armenians and the Christian congregations of Syria after the apostolic era.

Middle Ages

During the first half of the 7th century, Armenia was conquered by the Arab Islamic Caliphate. Thouands of Armenians were carried into slavery by the Arab invaders to serve in other regions of the Umayyad Caliphate including their capital Damascus in the Muslim-controlled Syria.[6]

During the 2nd half of the 11th century, Armenia -being under the Byzantine rule- was conquered by the Seljuq Turks. Waves of Armenians left their homeland in order to settle in more stable countries. Most Armenians established themselves in Cilicia where they founded the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. Many other Armenians have preferred to settle in northern Syria. Armenian quarters were formed during the 11th century in Antioch, Aleppo, Ayntab, Marash, Kilis, etc.

Prior to the Siege of Antioch, most Armenians were expelled from Antioch by the Turkish governor of the city Yaghi-Siyan, a move that prompted the Armenians of Antioch, and the rulers of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia to establish close relations with the European Crusades rather than the mostly-Turkish rulers of Syria. Thus, the new rulers of Antioch became the Europeans. Armenian engineers also helped the Crusaders during the Siege of Tyre by manipulating siege engines.

However, the Armenian population of Syria and its surrounding areas greatly diminished after the invasion of the Mongols under Hulagu Khan.

After the decline of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia during the 14th century, a new wave of Armenian migrants from the Cilician and other towns of northern Syria arrived in Aleppo. They have gradually developed their own schools and churches to become a well-organized community during the 15th century with the establishment of the Armenian Diocese of Beroea in Aleppo.

Ottoman Syria

During the early years of the Ottoman rule over Syria, there was relatively smaller Armenian presence in northern Syria due to the military conflicts in the region. A larger community existed in Urfa which is considered part of Greater Syria. The Ottoman Empire had a large indigenous Armenian population in its Eastern Anatolia region, from where some Armenians moved to Aleppo in search of economic opportunity. Later on, many Armenian families moved from Western Armenia to Aleppo escaping the Turkish oppression. Thus, large numbers of Armenians from Arapgir, Sasun, Hromgla, Zeitun, Marash and New Julfa arrived in Aleppo during the 17th century. Another wave of migrants from Karin arrived in Aleppo in 1737. There were also families from Yerevan.[7]

Armenian population increased in Aleppo. By the end of the 19th century, the Mazloumian family established the "Ararat hotel" that became a renowned international establishment and renamed Baron Hotel.

Armenian Genocide and the 20th century

.jpg)

Although the Armenians have had a long history in Syria, most arrived there during the Armenian Genocide committed by the Ottoman Empire. The main killing fields of Armenians were located in the Syrian desert of Deir ez-Zor (Euphrates Valley). More than a million Armenians were killed and hundreds of thousands fled historic Armenia. The native Arabs didn't hesitate to shelter and support persecuted Armenians. Arabs and Armenians have traditionally had good relations after Arabs sheltered the Armenians during the Armenian Genocide. There was also a minor Arab genocide in Anatolia at the same time.

Aleppo's large Christian population swelled with the influx of Armenian and Assyrian Christian refugees during the early 20th-century and after the Armenian Genocide and Assyrian Genocide of 1915. After the arrival of the first groups of Armenian refugees (1915–1922) the population of Aleppo in 1922 counted 156,748 of which Muslims were 97,600 (62.26%), native Christians -mostly Catholics- 22,117 (14.11%), Jews 6,580 (4.20%), Europeans 2,652 (1.70%), Armenian refugees 20,007 (12.76%) and others 7,792 (4.97%).[8][9]

The second period of Armenian flow towards Aleppo marked with the withdrawal of the French troops from Cilicia in 1923.[10] After the arrival of more than 40,000 Armenian refugees between 1923 and 1925, the population of the city reached up to 210,000 by the end of 1925, where Armenians formed more than 25% of it.[11]

According to the historical data presented by Al-Ghazzi, the vast majority of the Aleppine Christians were Catholics until the last days of the Ottoman rule. The growth of the Orthodox Christians is related with the arrival of the Armenian and Assyrian genocide survivors from Cilicia and Southern Turkey, while on the other hand, large numbers of Orthodox Greeks from the Sanjak of Alexandretta arrived in Aleppo after the annexation of the Sanjak in 1939 in favour of Turkey.

In 1944, Aleppo's population was around 325,000, with 112,110 (34.5%) Christians among which Armenians have counted 60,200. Armenians formed more than half of the Christian community in Aleppo until 1947, when many groups of them left for Soviet Armenia within the frames of the Armenian Repatriation Process (1946–1967).

Current status and the Syrian Civil War

Currently, most Armenians of Syria live in Aleppo, with smaller communities exist in Qamishli, Damascus, Kessab and Yacoubiyah, Ghnemiyeh and Aramo (Armenian villages in Latakia). In the capital Damascus, Armenians even have their own quarter known as "Hayy al Arman" (Quarter of the Armenians).

There are Armenians also in Latakia, Ar-Raqqah, Tell Abyad, Al-Hasakah, Al-Malikiyah and Ras al-Ayn.

However, as a result of the ongoing civil war in Syria, over 9,000 Syrian Armenians were living in Armenia as of December 2013.[12] Another 8,000 Armenians have arrived in Lebanon from Syria during 2013.

Organizations

The majority of Armenian organizations are based in the city of Aleppo, acting in the form of cultural, sport, youth or charitable associations:

Cultural associations based in Aleppo:

- Grtasirats Cultural Association (1924).

- Kermanig-Vasbouragan Cultural Association (1928).

- Hamazkayin Cultural and Educational Association (1930).

- Armenian Youth Association (1932).

- Tekeyan Armenian Cultural Association (1955).

- National Cultural Association (1955).

- Urfa Renaissance Cultural Association (1957).

- Nor Serount Cultural Association (1958).

- Cilician Cultural Association (1964).

- Syrian Youth Association (1978).

Charitable associations based in Aleppo:

- Armenian General Benevolent Union (1910).

- Armenian Syrian Red Cross Association (1919).

- National Orphanage (1920).

- Armenian Old Age Home (1923).

- Howard Karageozian Commemorative Corporation (1941).

- Jinishian Memorial Foundation (1966).

- Social Service Consultation of the Diocese of Beroea (1993).

Sports associations based in Aleppo:

- Armenian Sports Union, known as Homenmen sports and scouting organization established in Aleppo in 1921.

- Ararat Sports Union, founded in 1923, represented to the Syrian General Sports Federation under the name Ouroube SC.

- Armenian General Athletic Union, known as Homentmen sports and scouting organization, established in Istanbul in 1918 and opened branches in Syria in 1925, represented to the Syrian General Sports Federation under the name al-Yarmouk SC.

Students associations based in Aleppo:

- Karen Jeppe College Graduates Union (1947)

- Syrian-Armenian University Students Union (Ս.Հ.Մ., est. 1968).

- Graduates Union of Higher Institutions of Armenia (1982).

- Syrian Universities' Armenian Graduates Union (Ս.Հ.Շ.Հ.Մ., est. 1985).

- Dkhrouny Students-Youth Association (1969) of the Hunchakian party.

- Christapor Students Union (2001) of the Dashnak party.

Most associations have their branches in many other Syrian cities: Qamishli, Damascus, Latakia, Kessab, etc.

The Armenians of Aleppo have also formed compatriotic unions based on their roots, named after towns and villages where their ancestors have migrated from, during the Armenian Genocide. Nowadays, there are 11 compatriotic organizations operating in Aleppo: Dikranagerd, Daron-Duruperan, Marash, Urfa women's, Urfa youth, Palu, Zeitun, Kilis, Berejik, Musa Ler and Garmouj compatriotic unions.

Other notable community structures in Aleppo include:

- The National Cemetery, opened in 1927 on a state-owned piece of land. It became the property of the prelacy after the independence of Syria in 1946. The chapel of Surp Hripsimé stands at the centre of the cemetery since 1970.

- Avetis Aharonian theatre hall of the Armenian Prelacy, opened in 1959, renovated and renamed in 1989 (450 seats).

- Zavarian theatre hall of the Armenian Prelacy, opened in 1965, renovated in 2002 (350 seats).

- Kevork Nazarian theatre hall of AGBU, renovated and renamed in the mid-1990s (550 seats).

- Zohrab Kaprielian theatre hall of Grtasirats Cultural Association, opened in 1973, renovated and renamed in 1999 (600 seats).

- Kevork Yesayan theatre hall of the Armenian Prelacy, opened in 2005 (700 seats).

- Zarehian Treasury, opened in 1991 in the 15th-century building of the former Holy Mother of God church, near Forty Martyrs Cathedral. More than 650 valuable pieces are exhibited in the museum.

- Vergin Gulbenkian Hospital.

Religion

Armenians in Syria are mainly followers of the Armenian Apostolic Church, with a minority of Armenian Catholics and Armenian Evangelicals. The Church has a very important role in unifying Armenians in Syria.

After 301 AD, when Christianity became the official state religion of Armenia and its population, Aleppo became an important centre for the Armenian pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem. Yet, not considered an organized community in the city, Armenian presence was notably enlarged in Aleppo, during the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (12th century), when a considerable number of Armenian families and merchants settled in the city creating their own businesses, residencies, and gradually schools, churches and prelacy. The Armenian church of the Forty Martyrs in Aleppo was mentioned for the first time in 1476. In 1624, as a result of the growing number of Armenian residents and pilgrims, the Armenian prelacy started to build a quarter near the church which kept its original name Hokedoun (Spiritual House), up to now. It was designated to serve as a settlement for the Armenian pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem.

Apostolic Armenians

The majority of Armenians of the Armenian Apostolic (also known as Oriental Orthodox Armenian) faith are under the jurisdiction of the Holy See of Cilicia (based in Antelias, Lebanon) of the Armenian Apostolic Church. However, the Diocese of Damascus pledges allegiance to the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin.

The Apostolic Armenian population in Syria belongs to one of the 3 following prelacies:

- Diocese of Beroea (in Aleppo), was founded in 1432 by the Great House of Cilicia. Hovakim of Beroea became the first bishop of Aleppo between 1432 and 1442. The estimated population of the diocese all over Syria is about 70,000 Armenians.[13] The prelacy has the following church buildings under its jurisdiction in Syria:

- Forty Martyrs Cathedral of Aleppo (1491).

- Surp Krikor Lusavorich (Saint Gregory the Illuminator) Church of Aleppo.

- Surp Hagop Church of Aleppo (1943).

- Surp Kevork Church of Aleppo (1965).

- Church of the Holy Mother of God of Aleppo (1983).

- Surp Hripsime Church of Yacoubiyah village.

- Surp Anna Church of Yacoubiyah village.

- Holy Mother of God Church of Latakia.

- Holy Mother of God Church of Kessab.

- Holy Mother of God Church of Karadouran, Kessab.

- Surp Stepanos Church of Karadouran, Kessab.

- Surp Kevork Armenian Church of Ghnemiyeh village.

- Surp Stepanos Church of Aramo village.

- Holy Mother of God Church of Ar-Raqqah.

- Holy Cross Church of Tell Abyad.

- Armenian Genocide Martyrs' Memorial Church-Complex of Deir ez-Zor.

- Holy Resurrection Chapel of Margadeh village.

- Diocese of Jezireh (in Qamishli) under the jurisdiction of the Great House of Cilicia. The prelacy has the following church buildings under its jurisdiction in Syria:

- Surp Hagop Cathedral in Qamishli

- Surp Hovhannu Garabed Church in Al-Hasakah

- Holy Mother of God Church in Al-Malikiyah (formerly Dayrik)

- Holy Mother of God Church in Ras al-Ayn

- Diocese of Damascus under the jurisdiction of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin. The prelacy has the following church buildings under its jurisdiction in Syria:

Catholic Armenians

Catholic Armenians are members of the Armenian Catholic Church. The Catholic Armenian population in Syria belongs to one of the 4 following prelacies under the jurisdiction of the Armenian Catholic Patriarchate of Cilicia:

- Archeparchy of Aleppo: the first official Armenian Catholic Prelate in Aleppo was Bishop Abraham Ardzivian (1710–1740). In 1740, he became the first Armenian Catholic Catholicos-Patriarch of Cilicia, appointed by Pope Benedict XIV in 1742 in Lebanon. Currently, the number of the Catholic believers of the Armenian Catholic Archeparchy of Aleppo is approximately 15,000. The prelacy has the following church buildings under its jurisdiction in Syria:

- Cathedral of Our Mother of Reliefs of Aleppo (1840).

- Holy Saviour - Saint Barbara Church of Aleppo (1937).

- Church of Our Lady of Annunciation of Aleppo (1942).

- Holy Trinity Church of Aleppo (1965).

- Holy Cross Church of Aleppo (1993).

- Holy Mother of God - Martyrs Church of Ar-Raqqah.

- Patriarchal Exarchate of Damascus: the Armenian Catholic community in Damascus was organaized in 1763 during the period of Catholicos Michael Petros III Kasparian. In 1863, the firs Armenian Catholic church in Damascus was consecrated. The ground-breaking of the new church and the prelacy building in Bab Touma district took place in 1959. In 1969, the first Armenian Catholic bishop in Damascus was appointed. Since 1984, the Armenian Catholic bishop carries the title of Patriarchal exarchate. The prelacy has the following church building under its jurisdiction in Syria:

- Notre-Dame Cathedral of the Universe of Damascus.

- Eparchy of Qamishli: covers the eastern regions of Syria (Al-Jazira, Upper Mesopotamia) including the governorates of Al-Hasakah and Deir ez-Zor. The prelacy has the following church buildings under its jurisdiction in Syria:

- Saint Joseph Cathedral of Qamishli.

- Holy Family Church of Al-Hasakah.

- Saint Gregory the Illuminator Church of Deir ez-Zor.

- Diocese of Kessab: covers the Catholic Armenian population in the Latakia Governorate. The prelacy has the following church buildings under its jurisdiction in Syria:

- Saint Michael the Archangel Church of Kessab.

- Church of Our Lady of Assumption of Baghjaghaz, Kessab.

The Armenian Catholic Church has 2 Convents in Syria:

- The convent of the Immaculate Conception Sisters in Aleppo.

- The convent of Mekhitarist Fathers in Aleppo.

Evangelical Armenians

Armenian Evangelicals (also known as Armenian Protestants), belong to Union of the Armenian Evangelical Churches in the Near East of the Armenian Evangelical Church.

- The Armenian Evangelical community in Syria has the following church buildings:

- Emmanuel Church of Aleppo.

- Bethel Church of Aleppo.

- Martyrs' Church of Aleppo.

- Church of Christ of Aleppo.

- Holy Trinity Church of Kessab.

- Emmanuel Church of Ekizolukh, Kessab.

- The Armenian Evangelical Church of Keorkeuna, Kessab.

- The Armenian Evangelical Church of Karadouran, Kessab.

Education

The education is an important factor in maintaining Armenian language and patriotism among the Armenian community in Syria. Aleppo as the main host of the community, is a center of Armenian long-running schools and cultural institutions. Armenian students who graduate from those community schools, can immediately enter the Syrian university system, after passing the official Thanawiya 'Amma (High School baccalaureate) exams.

Armenian schools in Aleppo

A total of 9 schools operate in Aleppo including 4 secondary education schools (high schools):

- Karen Jeppe Armenian College, the first Armenian secondary school in Aleppo. It was opened in 1947 on a piece of land in Meydan quarter transferred to the Armenian Prelacy by the will of the Danish philanthropist Karen Jeppe. The school was founded by the initiative of then-bishop Zareh Payaslian (the future Catholicos Zareh I of the Holy See of Cilicia). The school building has been expanded gradually in 1966, 1973 and 1986. Nowadays, the college has more than 1,100 mixed students with only secondary section of six grades. The school is operating under the direct administration of the Armenian prelacy of Aleppo.

- AGBU Lazar Najarian-Calouste Gulbenkian Armenian Central High School, was founded as Lazar Najarian Central School in 1954 by the efforts of the Armenian General Benevolent Union. It was turned into a high school with a secondary section in 1959 and renamed as Lazar Najarian-Calouste Gulbenkian Central High School. The elementary and the secondary sections are located in two adjacent buildings, while the kindergarten has its own newly erected building. The school has more than 1,500 mixed students and is operating under the administration of the Syrian Regional Central Committee of the Armenian General Benevolent Union. The school has its own theatre hall named after its benefactor "Kevork Hagop Nazarian".

- Cilician (Giligian) Armenian High School, a 12 grade mixed high school founded in 1921. It has three sections: nursery, elementary and secondary, each of them has its own separate building located along the Sissi alley of the old Christian quarter of Jdeydeh. At the beginning, the school was founded in 1921 as Cilician Refugees School by the efforts of the Cilician Relief Association. In 1930, it was renamed Cilician School and subsequently; Cilician High School after the foundation of the secondary section in 1960. The Cilician School is operating under the administration of Cilician Cultural Association with more than 450 mixed students.

- Grtasirats High School, founded in 1924 as Aintab's Grtasirats Mixed School through the efforts of "Aintab's Grtasirats Association". Up to 1974, the school was operating in the old Christian quarter near Jdeydeh, when it was moved to a new modern building in Sulaimaniyah district. It has a kindergarten, an elementary section, and since 2004; a secondary section. The school is under the administration of Grtasirats Cultural Association, and has more than 300 mixed students. Adjacent to the school, the Armenian church of the Holy Mother of God was opened in 1983. The school has its own "Zohrab Kaprielian" theatre hall, one of the largest ones in Aleppo.

Other Elementary schools in Aleppo under the administration of the prelacy:

- Haygazian Primary School, established in 1919. the school is considered to be the continuation of the "Tebradoun" (est. in 1876) and the Nersessian School. Located within the complex of the Forty Martyrs Cathedral in Jdeydeh quarter, the school has a six-years mixed elementary section with more than 800 students. The kindergarten is operating in the Meydan quarter. The school has a theatre hall named after Avetis Aharonian.

- Zavarian Primary School, originally founded as Nersessian School in 1925 with a centre adult orphans. On 15 August 1936, the two sections have been merged in one building in the Meydan quarter. The new school, along with its theatre hall were renamed after Simon Zavarian. The building was totally renovated in 1965. Nowadays, it has a six-years mixed elementary section and a kindergarten. The total number of the students is more than 450.

- Sahakian Primary School, founded in 1927 by the donation of the Armenian diaspora of India and Brazil. It was named after Catholicos Sahak II Khabayan of the Holy See of Cilicia. It is located in the Meydan quarter since 1932 within the complex of Saint Gregory Armenian church. The school was expanded in 1962 with the erection of a new building. Nowadays, the school has a six-years mixed elementary section and a kindergarten with more than 850 the student.

- Gulbenkian Elementary School, founded on 22 September 1930 as Boghos Gulbenkian school by the donation of the Armenian benefactor Nerses Gulbenkian from London. Up to 1996, the school was operating in a small building located in a narrow street in the Sulaimaniyah district. On 13 June 1997, the new modern building of the school was inaugurated in Suleimaniyeh area with the presence of Catholicos Aram I. Currently, the school has a six-years elementary section and a kindergarten with more than 500 mixed students. The school has its own "Kevork Yesayan" theatre hall.

Defunct schools, mainly closed due to the Armenian Repatriation Process to Soviet Armenia between 1946 and 1967:[14]

- Mesropian Primary School (1923-2011): was a six-year elementary school opened in the Armenian refuge camp of Ram of Suleimaniyeh district in 1923, being known as the Camp's Mesropian Mixed School. In 1936, it was relocated to the Armenian-populated Meydan quarter as part of the proposed Surp Kevork Church complex (eventually consecrated in 1965). The nursery section of the school was operating in a small building adjacent to the Surp Kevork church. In 2003, the total number of the students of the mixed school was 200. Finally, in 2011 the school was closed just after the break-up of the Syrian Civil War.

- Armenyan Primary School (1923-1979): was located in the Sheikh Maqsoud district.

- Aramian Primary School (1930-1977): was located in the Assyrian district.

- Vartanian Primary School (1936-1980): was located in the Ashrafiyeh district.

- Kermanigian Primary School (1937-1974).

- Ousumnasirats-Levonian Primary School (1945-1964).

Armenian schools in other Syrian regions

- Yeprad (Euphrates) High School, Qamishli, founded in 1932 and has 9 grades since 1962. Currently, it has more than 900 students.

- Azadutyun (Liberty) Primary School, Al-Malikiyah (Dayrik).

- Mesrobian School, Al-Hasakah.

- Nahadagats (Martyrs') Primary School, Ras al-Ayn.

- Khorenian Primary School, Tell Abyad.

- Noubarian Primary School, Ar-Raqqah.

- Veradzenount (Rebirth) Primary School, Yacoubiyah.

- Nahadagats (Martyrs') Primary School, Latakia.

- Osumnasirats Miyatsyal High School, Kessab.

- Tarkmanchats (Holy Translators) High School, Damascus.

- Ousumnasirats Primary School, Damascus.

- AGBU Gyullabi Gulbenkian Primary School, Damascus.

- Sahakian Primary School, Homs.

defunct schools:

- Mesropian Primary School, Jarabulus (1933-1944).

- AGBU Vartanian Primary School, Jarabulus (1935-1944).

- Khrimian Primary School, Ayn al-Arab (1927-1962).

- AGBU Avedis Sarafian Primary School, Ayn al-Arab (1950-1975).

Integration of the Armenian communities in Syria

Political life

Syrian Armenians were integrated in the poltitcal life since the Ottoman rule over Syria. Artin Boşgezenyan was a deputy for Aleppo in the first (1908–1912), second (April–August 1912) and third (1914–1918) Ottoman Parliaments of the Constitutional Era.[15]

After the establishment of the Syrian state, Hrant Maloyan an Armenian General officer from Muş had served as the head of Syrian Security Forces during the 1940s and 1950s. On the other hand, another Armenian military General officer from Ayntab; Aram Karamanougian had became the artillery commander of the Syrian Army during the same period.

Armenians have had almost continuous representation in the Syrian Parliament from 1928 onwards. The Armenian-Syrian members of Parliament were (in chronological order) Mihran Puzantian, Fathalla Asioun, Nicolas Djandjigian, Movses Der Kalousdian (later on also MP in the Lebanese Parliament), Hratch Papazian, Henri Hendieh (Balabanian), Hrant Sulahian, Bedros Milletbashian, Ardashes Boghigian, Nazaret Yacoubian, Movses Salatian, Dikran Tcheradjian, Fred Arslanian, Abdallah Fattal, Louis Hendieh, Krikor Eblighatian, Aram Karamanougian, Roupen Dirarian, Levon Ghazal, Simon Ibrahim Librarian and Sunbul Sunbulian (until 2012). However, as a result of the 2012 parliamental elections, currently the People's Council of Syria does not have any Armenian member.

The current Cabinet of Syria has one Armenian member after Nazira Farah Sarkis has been named as State Minister for Environment Affairs in June 2012.

Persecution

As of November 2014, only 23 Armenian and Assyrian Christian families remain in the city of Ar-Raqqah. Christian bibles and holy books reportedly been burned by ISIS militants.[16][17][18]

Media

Syria has a rich tradition of media and publications in Armenian language. Armenian dailies -currently defunct- had a great run at the beginning of the 20th century. The daily Hye Tsayn (1918–1919), one-every-two-days Darakir (1918–1919) and Yeprad (1919) were among the first published newspapers.

A stream of publications followed in the twenties and the thirties of the 20th century: Souriagan Sourhantag (1919–1922), Souriagan Mamul (Syrian Press, 1922–1927), the dailies Yeprad (1927–1947), Souria (1946–1960) and Arevelk (1946–1963). The latter had also its annual yearbook. Arevelk had also published 1956 its youth supplement Vahakn (1956–1963) and its sports supplement Arevelk Marzashkharh (1957–1963).

Monthly papers included Nayiri (1941–1949) published by Antranig Dzarugian, and Purasdan youth publication (1950–1958).

Yearbooks include Souriahye Daretsuyts (1924–1926), Datev (1925–1930), Souriagan Albom (1927–1929), Daron (1949), Hye Darekirk (1956) and Keghart (since 1975).

Currently, Kantsasar weekly is the official organ of the Armenian Diocese of Beroea in Aleppo. It was first published as Oshagan in 1978 and was renamed Kantsasar in 1991.

Syrian publishers have a great contribution in translating several Armenian literature and academic studies into Arabic. It is noteworthy that the first evere Arabic language newspaper was published by the Aleppine Armenian journalist Rizqallah Asdvadzadur Hassoun in 1855 in Constantinople.[19]

Sport

Al-Yarmouk and Ouroube are Syrian-Armenian sports clubs based in Aleppo. Being among the oldest sporting clubs in Syria, al-Yarmouk and Ouroube have several teams participating in different Syrian National competitions including football, basketball (men and women), table tennis, chess and other individual sports. The clubs have their own training grounds in the city of Aleppo.

During the first half of the 1940s and 1950s, many Armenian players had represented the Syrian football on the national level including Ardavazt Marutian and Kevork Gerboyan. The former player and trainer Avedis Kavlakian of the 1960s was selected by the Syrian press as the best Syrian footballer of the 20th century. Kevork Mardikian from Latakia is a prominent football trainer and one of the best Syrian footballers during the 1970s and 1980s. Nowadays, his son Mardik Mardikian is a member of the Syria national football team.

In basketball, Mary Mouradian, Ani Karalian, Elisabeth Mouradian and Magi Donabedian were members of the Syria women's national team during the 1980s and 1990s. Sari Papazian and Vatche Nalbandian from Aleppo are current members of the Syria men's national basketball team.

Music, arts and drama

Many Armenians from Syria had achieved national and international fame in the spheres of music and drama. Salloum Haddad from the Armenian village of Yacoubiyah is a famous contemporary actor in Syrian and Arab drama. Ruba al-Jamal (died in 2005) was a prominent classical Arabic songs performer born as Dzovinar Garabedian. Many other Syrian-Armenian singers and musicians became renowned artists among Armenians around the world like George Tutunjian, Karnig Sarkissian, Paul Baghdadlian, Setrag Ovigian, Arsen Grigoryan (Mro), Karno and Raffi Ohanian. Many others have achieved international fame including Aram Tigran, Haig Yazdjian, Avraam Russo, Wadi' Mrad, Talar Dekrmanjian and Lena Chamamyan. The conductor of the Syrian National Symphony Orchestra is Missak Baghboudarian from Damascus.

Armenian theatres in Aleppo include:

- Antranig Theatre Group of the Nor Serount Cultural Association.

- Bedros Atamian Theatre Group of the Armenian Youth Association.

- Zavarian Theatre Group of the Hamazkayin Cultural and Educational Association.

- Levon Shant Theatre Group of the Hamazkayin Cultural and Educational Association.

- Kermanig-Vasbouragan Theatre Group of the Kermanig-Vasbouragan Cultural Association.

- Vartan Ajemian Theatre Group of the Grtasirats Cultural Association.

Armenian musical ensembles in Aleppo include:

- Zvartnots Choir of the Hamazkayin Cultural and Educational Association.

- Alexander Spendiaryan Choir of the Armenian Youth Association.

- "Big Band" musical group of the Armenian Youth Association.

- Gomidas Chamber Orchestra of the Armenian Youth Association.

- Meghri Children's Choir of the Hamazkayin Cultural and Educational Association.

Armenian dance groups in Aleppo include:

- Nor Serount Dance Group of the Nor Serount Cultural Association.

- Sartarabad Dance Group of the Hamazkayin Cultural and Educational Association.

- Jirayr Dance Group.

- Antranig Dance Group of the Armenian Youth Association.

- Uno Dance Group.

- Shushi Chldren's Dance Group of the Hamazkayin Cultural and Educational Association.

Armenian art academies in Aleppo include:

- Martiros Saryan Painting Academy of the Armenian Youth Association.

- Arshile Gorky Painting Academy of the Hamazkayin Cultural and Educational Association.

- Aram Khachaturian Musical Academy of the Armenian Youth Association.

- Barsegh Kanachyan Musical Academy of the Hamazkayin Cultural and Educational Association.

Medical sciences

Armenians were among the pioneers of modern medical sciences in Syria. The first X-ray generator in Syria and Lebanon was brought by Dr. Asadour Altunian (1857-1950) to Aleppo in 1896.[20] Dr. Altunian opened the first-ever private hospital in Aleppo in 1927. Later, he founded the first nursing school in Aleppo and Syria. After his death in 1950, Dr. Asadour Altunian was honoured by the government of Syria with the Honour Medal of Syrian Merit of the Excellent Degree.[21] In ophthalmology, Dr. Robert Jebejian (1909-2001) was among the first ophthalmologists in Syria. He founded the first-ever private ophthalmological hospital in Aleppo in 1952.[22] Dr. Jebejina had published many valuable researches about leishmaniasis and trachoma.[23] In 1947, Dr. Jebejian performed the first-ever corneal transplantation surgery in the Middle East and the Arab World.[24]

Syrian-Armenian Relations

Deir ez-Zor and the Armenian Genocide

In 1915, the Syrian region of Deir ez-Zor, mainly a desert became a final destination of the Armenians during Armenian Genocide where they were killed. A memorial complex commemorating this tragedy was opened in the city.[25] It was designed by Sarkis Balmanoukian and was officially inaugurated in 1990 with the presence of the Armenian Catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia. The complex contains bones and remnants recovered from the Deir ez-Zor desert of Armenian victims of the Genocide and has become a pilgrim destination for many Armenians in remembrance of their dead.

Kessab, Syrian town with an Armenian majority

Kessab (Arabic: كسب, Armenian: Քեսապ) is a Syrian border town located in the Latakia Governorate northwest of Syria at a height of 800 meters above sea level just 3 kilometers away from the Turkish border, and 9 kilometers from the Mediterranean sea.

Kessab is an ancient Armenian town, over 1000 years old. Today, The population of the town and the surrounding villages is mainly Armenian[26] with a minority of Syrian Arab.

Kessab is a touristic summer resort and a very popular destination.

Relations between Syria and Armenia

The Armenian embassy of Damascus (since 1992), was the first Armenian embassy opened abroad after the independence of Armenia. The official visit of the newly elected Armenian president Levon Ter-Petrossian to Syria in 1992, was the first international official visit of an Armenian president after the independence. Since then, the relations between the two countries are developing especially after the creation of a joint economical committee between the two governments and the establishment of co-operation between the commercial chambers of Aleppo and Armenia since 2008. The recent visit of president Bashar al-Assad to Yerevan in June 2009, came to maintain the bilateral relations.

Armenia has also a consulate general in Aleppo since 28 May 1993. In 1997, the Syrians opened their embassy in Yerevan which is located on Baghramyan street, few meters away from the presidential palace.

The first president of the new Republic of Armenia Levon Ter-Petrosyan was born in Aleppo, Syria.

See also

- List of Syrian Armenians

- Armenia–Syria relations

- Armenian Diocese of Beroea

- Kessab

- Yacoubiyah, Syria

- Karen Jeppe

References

- ↑ "Syrian Armenians in Armenia: Home away from home?". The Economist. 12 December 2013.

- ↑ "THE VIRTUAL MUSEUM OF ARMENIAN DIASPORA". Ministry of Diaspora of the Republic of Armenia. Retrieved 2014-02-19.

- ↑ UsaToday.com: Armenia tries to help as Christian Armenians flee Syria

- ↑ "Around 10,000 Syrian Armenians moved to Armenia and 8,000 to Lebanon - Shahan Ka". Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ Unknown, Unknown. "Wahhabi / Takfiri Cleric Smashes a Statue of the Virgin Mary in town of Yakubiyah". Orontes. jimdo.com. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ↑ Kurkjian, Vahan M.A History of Armenia hosted by The University of Chicago. New York: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America, 1958 pp. 173-185

- ↑ Aztag Daily, 10 February 2000, article edited by Mania Ghazarian and Ashod Sdepanian

- ↑ Alepppo in One Hundred Years 1850–1950, vol.3-page 26, 1994 Aleppo. Authors: Mohammad Fuad Ayntabi and Najwa Othman

- ↑ The Golden River in the History of Aleppo, (Arabic: ﻧﻬﺮ ﺍﻟﺬﻫﺐ ﻓﻲ ﺗﺎﺭﻳﺦ ﺣﻠﺐ), vol.1 (1922) page 256, published in 1991, Aleppo. Author: Sheikh Kamel Al-Ghazzi

- ↑ The Golden River in the History of Aleppo (Arabic: ﻧﻬﺮ ﺍﻟﺬﻫﺐ ﻓﻲ ﺗﺎﺭﻳﺦ ﺣﻠﺐ), vol.3 (1925) pages 449–450, published in 1991, Aleppo. Author: Sheikh Kamel Al-Ghazzi

- ↑ Hovannisian, Richard G. (2004). The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 425. ISBN 1-4039-6422-X.

- ↑ "Kuwait donates USD 100,000 to Armenia for humanitarian aid to Syria refugees". Kuwait News Agency. 26 December 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ↑ "Diocese of Aleppo, History". Diocese of Aleppo.

- ↑ Hayrenik Weekly: Armenians of Syria

- ↑ Aktar, A. (2007). "Debating the Armenian Massacres in the Last Ottoman Parliament, November December 1918". History Workshop Journal 64: 240. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbm046.

- ↑ "23 Christian Families Trapped in ISIS Stronghold Raqqa Facing Violence, Forced Taxes". Christian Post. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ "23 Families Left in Syria's Raqqa After ISIS Control". Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ "25 Christian families still in Raqqa. Obligation to pay a "protection tax" - Fides News Agency". Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ The Syrian press, the past and the present, by Hashem Osman, 1970 Damascus (الصحافة السورية ماضيها وحاضرها –هاشم عثمان– 1970 دمشق)

- ↑ "جواهر حلب". Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ "أعلام الأطباء في حلب - الطبيب أسادور ألتونيان". Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ "موقع حلب - "روبيرت جبه جيان".. مفهوم جديد للواقعية التعبيرية". Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ Artsgulf: Robert Jebejian

- ↑ "معرض لوحات للدكتور جبه جيان". Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ "Monument and Memorial Complex at Der Zor, Syria". Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ Mannheim, Ivan (2001). Syria and Lebanon Handbook: The Travel Guide. Footprint Travel Guides. p. 299. ISBN 1-900949-90-3.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Armenian churches in Syria. |

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||