Armenian resistance during the Armenian Genocide

| Armenian Resistance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War I | |||||

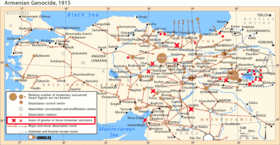

Conflicts of 1915 (red stars) | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

| Ottoman Empire | Armenian Militia of Armenakans (Ramkavars), Hnchakians (Social Democrat Hunchakian Party), and Dashnaktsutiun (Armenian Revolutionary Federation) | ||||

The Armenian resistance is a name given to the military and political activities of the Armenians under the Armenian political parties of Henchak, Armenakan, Dashnaktsutiun against the Ottoman Empire during World War I, considered a struggle for freedom and resistance to the Armenian Genocide by the Armenian combatants, but high treason by the Ottoman Empire. These Armenian national organizations established Armenian Fedayee (Armenian: Ֆէտայի) generally referred to as Armenian partisan guerrilla detachments and the Russian Empire formed Armenian volunteer units, which recruited Ottoman Armenians from behind the Ottoman lines, to help the Russian Caucasus Army against the Ottoman Empire.[1] During this initial period Siege of Van on April 20, 1915, and consequently establishment of Administration for Western Armenia were significant events, that according to minister of interior Mehmed Talat Pasha this rise of Armenian national liberation movement and the Fifth column activity as stated in his order on April 24, 1915 ended with arrests in Red Sunday and later Ottoman parliament passed Tehcir Law on 29 May 1915, which enabled the massive deportation of the Armenian people from the region.

The deportations and massacres, resulting in the deaths of about 1,500,000 Armenians,[1] is referred to as the Armenian Genocide by most scholars of the period; official Turkish sources often refer to it as the ″Armenian insurgency", and dispute the number of victims.

Background

There were previous Armenian resistances within the Ottoman Empire. The Sasun resistance of 1894 (Armenian: Սասնո առաջին ապստամբութիւն) was the resistance of the Hunchak militia of the Sassoun region. The Zeitun Rebellion took place in 1895, during the Hamidian massacres. The Defense of Van was the Armenian population in Van defense against the Ottoman Empire in June, 1896. The Khanasor Expedition (Armenian: Խանասորի Արշաւանքը) was the Armenian militia's response on July 25, 1897 to the Defense of Van, where Mazrik tribe ambushed a squad of Armenian defenders and mercilessly slaughtered them. The Sasun uprising was the resistance of the Armenian militia in the Sassoun region. Mourat together with his companion, Sepouh, had fought at Sasoun, in 1904, and had taken part in the Armenian and Tartar clashes of 1905 and 1906 in the Caucasus.

Sassouni, a Tashnak, argues that the Ottoman Empire's fundamental aim was to resolve the Armenian question by massacring the Armenian people and the Armenian national liberation movement's achievement between 1908 to 1914 (what was named as pre-genocide period) was the preparation and organization of nation-wide armed resistance for the targets which were only forces against Armenian Revolutionary Federation.[2]

Forces

The Armenian forces which engaged with the resistance to Ottoman Forces were the Armenian civilian volunteers (Kamavor) who are literally "one who is ready to sacrifice his life" who leave their families to form brigades.[3] Most of the leaders of the volunteers were also leaders and members of the Armenian national liberation movement. Some of the famous leaders were Murad of Sebastia, and Karekin Pastermadjian. Karekin Pastermadjian and his group joined to the Armenian volunteer units. Some Armenians claimed that only the Russian Tsar, by virtue of shared religion, was the protector of all Armenians.[4] Armenian volunteer units were established along the Russian Tsar's Army, Russian Caucasus Army, dating back to the summer of 1914.[5] In several towns occupied by the Russians the Ottoman Armenian students have shown themselves ready to join this Armenian volunteer army.[6] Negotiations of Boghos Nubar, who was the elected speaker for the Armenian National Assembly (Ottoman Empire), with French political and military authorities culminated in the formation of the French Armenian Legion with the French-Armenian Agreement (1916). Many of the Armenian volunteers for French Armenian legion were survivors from Musa Dagh.[7] Beginning with 1917, Armenian National Organization of the Caucasus, Armenian National Council, asked the Armenian soldiers and officers scattered throughout Russia to gradually brought together.[8] The plan was to mobilized Armenians on the Caucasian front against the Ottoman Forces.[8] The call for arms, by the Armenian National Organization, also received response with Ottoman Armenian civilian forces, such as Murad of Sebastia, who fought bravely with these forces and died at the battle fields Baku.

Ottoman Third Army was the major force in the Caucasus Campaign that acted against the Armenian forces. Mahmut Kamil was the commander of the Third Army[9] After the armistice of Mudros, Mahmut Kamil was one of the Malta exiles.

Activities

1914

In the spring of 1914, there were intercepted letters from Armenian political organizations expressing concern over the developments regarding World War I, which Ottoman Empire was neutral at the moment.[10] In one of these documents, the ARF requested weapons from the Russians.[10]

In July 1914, at the beginning of this world conflagration, in 1914, both the Russian and the Turkish governments officially appealed to various Armenian national organizations with many promises in order to secure the active participation of the Armenians in the military operations against each other at the Armenian congress at Erzurum[11] The main of opposition in Ottoman Empire to Turco-German alliance was the Armenian people, who for four years and without an organized government or a national army, played the same role in the Near East by preventing the Turco-German advance toward the interior of Asia as the Belgians played in the West by arresting the march of Germany toward Paris.[11] After this meeting the CUP was convinced on strong Armenian—Russian links with detailed plans aimed at the detachment of the region from the Ottoman Empire.[12]

In August 1914, at Zeitun Resistance the Hunchaks resisted to the Ottoman Military in the city Zeitun.

In September, 1914, Erzurum Fortress reported to Ottoman Headquarters that they received a report that the Armenian regiments were mobilized and were conducting war-training exercises.[10] There were reports from Ottoman infantry battalions in the region concerning Armenian meetings at which large numbers of Armenian nationals were gathering in secret meetings.[10] The Ottoman military was uncomfortable as they recognized that thousands of Ottoman Armenian citizens were deliberately leaving their homes in Ottoman territory.[10] These initial migrations may have many reasons, such as Armenians afraid of possible violence move to regions which they feel secure. Although Ottoman Empire was neutral on the paper, many Ottoman officers were convinced that Russia was actively preparing the war zone.[10]

In October 1914, a patrolling Ottoman unit (October 20) in Koprukoy discovered Russian rifles cached in Armenian homes in Hasankale.[10] The Third Army was received reports of Armenians that served in Russian Army returning to Empire with operation maps and financial resources.[10]

On November 2, 1914, Bergmann Offensive was the first engagement of the Caucasus Campaign[13] The Russian success was along the southern shoulders of the offense where Armenian volunteers were effective and took Karaköse and Doğubeyazıt.[14]

On December 29, 1914, the Battle of Sarikamis was a stunning Ottoman defeat. The Armenian detachment units credited no small measure of the success which attended by the Russian forces, as they were natives of the region, adjusted to the climatic conditions, familiar with every road and mountain path, and had real incentive to fierce and resolute combat.[15] Armenian detachment battalions challenged the Ottoman operations during the critical times: "the delay enabled the Russian Caucasus Army to concentrate sufficient force around Sarikamish".[16]

In the fall of 1914, (November, December, and into January 1915) substantial size of reports fall into the General Staff in Constantinople outlined the insecurity (danger) posed by armed Armenian militia's in the Third Army (Caucuses) and in the Fourth Army (Mediterranean region) areas.[12] Incidents of bombings and assassinations of civilians and local officials increased during this period.[12]

1915

On February 25, 1915, the famous "Directive 8682" was issued and distributed secretly in the form of a ciphered cable. The directive was received by the First, Second, Third, and Fourth Armies; the Iraq Command: I, II, III, IV, V Army Corps: and to the Jandarma Command, where the Armenian population was dominant. The title of the directive was "Increased Security Precautions". The directive began with summarising dissident Armenian activity in Bitlis, Aleppo, Dortyol, and Kayseri.[12] The directive stated that the Russians and French had influence on activities in these areas.[12] Finally, the directive ordered any ethnic Armenian soldiers should be removed from headquarters staff and taken out of command centers.

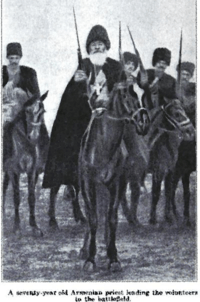

From February through July 1915, a great many additional reports from provincial officials and lower level army units reinforced the pattern of allied intelligence gathering of Ottoman military activities.[12] The Ministry of the Interior’s Intelligence Division noted that the Armenian Patriarchate in Constantinople was transmitting military secrets and dispositions to the Russians.[12] It was believed at this time that a seventy-year-old priest was leading Armenians[17]

On March 25, Hunchaks of the city Zeitun begun the second Zeitun Resistance.

In April, around 30,000 Armenians in the city of Van, in addition to the Armenians from surrounding villages, defended themselves during the Siege of Van.[18] The biggest achievement was the establishment of the Administration for Western Armenia with Aram Manukian at the head. Armenian forces kept the Ottomans out by at the cost of thousands of civilians killed. The initial armed resistance lasted for a period of less than a month. In May, the Armenian volunteer units and Russian Caucasus Army entered the city and successfully drove the Ottoman army out of Van.[18]

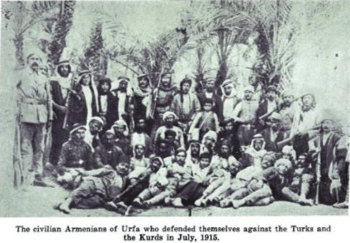

On May 27, hundreds of Armenians were captured by Ottoman authorities in Urfa after the Urfa Resistance. At Urfa the Armenians repulsed the attacks of one division, but finally fell under heavy fire from artillery commanded by German officers. The Armenians destroyed all their property so that it would not fall into the hands of the Ottomans or Germans.

In July, the resistance of Mourat and his comrades occurred at Sivas. When deportations were ordered gendarmes were sent to capture Mourat, Mourat defended himself with his compatriots for a year and a half.[16] On June 15, the Ottoman government hanged the The Twenty Martyrs. Armenians resisted for a month with Shabin-Karahisar uprising until Neshed Pasha left Sivas with three regiments and artillery to subdue them.

On August 19, Armenian defended the city of Van for a second time until the arrival of Russian army with Andranik Ozanian lifted the siege.

1916

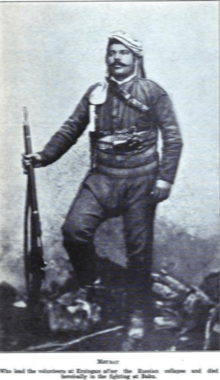

In 1916, Murad moved to Samsun, with a sail-boat traveled to the Russian port of Batoum. He led his volunteers to the Battle of Erzinjan.[16]

1918

In May, there were fierce combats between the Armenians who remained firm and the Ottoman forces beginning with the battle of Abaran. Between May 24–26, Armenians under Movses Silikyan defeated the Ottoman troops in a three-day battle of Sardarapat. Between May 24–28, the Armenian defenders at battle of Karakilisa managed to turn back the outnumbered invading Ottoman forces, After violent battle for 4 days both parties had serious losses, Ottoman army had no more forces to continue deeper into Armenian territory.

In September, Mourat and his volunteers were at Battle of Baku, where he died in the fighting.[16]

Art and culture

Armenian resistance has left a symbolic dish. The "Harissa (dish)" (Armenian: Հարիսա): is generally served to commemorate the Musa Dagh resistance. Current practice renamed the dish as "hreesi".

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Encyclopædia Britannica: Armenian Genocide

- ↑ Garo Sassouni, A Critical Look at the 1915 Genocide, 1930, page 40.

- ↑ "Middle East Glossary". The Israel Project. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ↑ William Ochsenwald, Sydney Nettleton Fisher, The Middle East: A History, Volume I. Publisher: McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages; 6 edition (June 4, 2003) ISBN 978-0-07-244233-5 Page 380

- ↑ Hovannisian “The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times “ p 280

- ↑ The Washington post Friday, November 12, 1914. Armenians Join Russians; look at the image detail for explanation

- ↑ Walker. "World War I and the Armenian Genocide", p. 267.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 (Pasdermadjian 1918, pp. 38)

- ↑ Keith Neilson, 1983, Coalition Warfare, Published by Wilfrid Laurier University Press, page 49 ISBN 978-0-88920-165-1; W.E.D. Allen and Paul Muratoff, Caucasian Battlefields, A History of Wars on the Turco-Caucasian Border, 1828–1921, 311. ISBN 0-89839-296-9

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 (Erickson 2001, pp. 97)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 (Pasdermadjian 1918, pp. 15)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 (Erickson 2001, pp. 98)

- ↑ (Hinterhoff 1984, p. 500)

- ↑ (Erickson 2001, pp. 54)

- ↑ The Hugh Chisholm, 1920, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Company ltd., twelve edition p.198.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 (Pasdermadjian 1918, pp. 22)

- ↑ (Pasdermadjian 1918, pp. 14)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Hayots Badmoutioun (Armenian History) (in Armenian). Hradaragutiun Azkayin Oosoomnagan Khorhoortee, Athens Greece. pp. 92–93.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Armenian resistance. |

- Erickson, Edward J. (2001). Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31516-9.

- Ussher, Clarence D. (1917). An American Physician in Turkey. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Méndez, Rafael Méndez (1926). Four Years beneath the Crescent. London: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 1-903656-19-2.

- Pasdermadjian, Garegin; Aram Torossian (1918). Why Armenia Should be Free: Armenia's Role in the Present War. Hairenik Pub. Co. p. 45.

| |||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||