Arctic sea ice decline

Arctic sea ice decline describes the sea ice loss observed in recent decades in the Arctic Ocean. The IPCC AR4 reported that greenhouse gas forcing is largely, but not wholly, responsible for the decline in Arctic sea ice extent. More recent studies found the decline to be “faster than forecasted” by model simulations.[1] The IPCC AR5 report concluded with high confidence that sea ice continues to decrease in extent and there is robust evidence for the downward trend in Arctic summer sea ice extent since 1979.[2] It has been established that the region is at its warmest for at least 40,000 years and the Arctic-wide melt season has lengthened at a rate of 5 days per decade (from 1979 to 2013), dominated by a later autumn freezeup.[3] Sea ice changes have been identified as a mechanism for polar amplification.

Observation

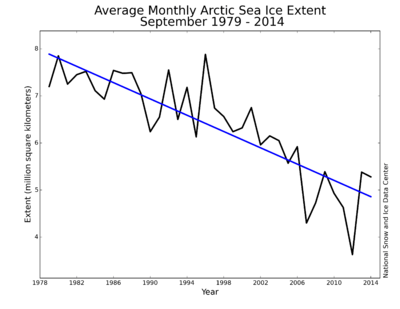

Observation with satellites show that sea ice has been in decline for a few decades in area, extent, and volume. Sometime during the 21st century, sea ice may completely cease to exist during the summer. Sea ice extent is defined as the area with at least 15% ice cover.[4] The amount of multi-year sea ice in the Arctic has declined considerably in recent decades. In 1988, ice that was at least 4 years old accounted for 26% of the Arctic's sea ice. By 2013, ice that age was only 7% of all Arctic sea ice.[5]

Scientists recently measured sixteen-foot (five-meter) wave heights during a storm in the Beaufort Sea in mid-August until late October 2012. This is a new phenomenon for the region, since a permanent sea ice cover normally prevents wave formation. Wave action breaks up sea ice, and thus could become a feedback mechanism, driving sea ice decline.[6]

Ice-free summer?

An "ice-free" Arctic Ocean is often defined as "having less than 1 million square kilometers of sea ice", because it is very difficult to melt the thick ice around the Canadian Arctic Archipelago;[7][8][9] the IPCC AR5 defines "nearly ice-free conditions" as "when sea ice extent is less than 106 km2 for at least five consecutive years" and (for at least one scenario) estimates that this might occur around 2050.[2]

Many scientists have attempted to estimate when the Arctic will be "ice-free". In doing so, they have noted that climate model predictions have tended to be overly conservative regarding sea ice decline.[10][11] A 2006 paper by Marika Holland et al. predicted "near ice-free September conditions by 2040".[12] Overland & Wang, in 2009, predicted that there would be an ice-free Arctic in the summer by 2037.[13] The same year Boé et al. found that the Arctic will probably be ice-free in September before the end of the 21st century.[14]

A follow-up study by Overland & Wang in 2013, concluded with the possibility of major sea ice loss within a decade or two.[15] The Third National Climate Assessment (NCA), released May 6, 2014, reports that the Arctic Ocean is expected to be ice free in summer before mid-century. Simulations by global climate models generally map well to this seasonal pattern of observed Arctic sea ice loss. Models that best match historical trends project a nearly ice-free Arctic in the summer by the 2030s.[16] However, these models do tend to underestimate the rate of sea ice loss since 2007.

In 2010 Wieslaw Maslowski concluded that "Near ice-free summer Arctic might become a reality much sooner than GCMs predict";[17] this was reported in the press as "US Navy predicts summer ice free Arctic by 2016" [18]

Implications

Implications which arise from lesser ocean surface covered with sea-ice include the ice-albedo feedback or warmer sea surface temperatures which increase ocean heat content, which in turn changes evaporation patterns and the polar vortex.

Atmospheric chemistry

Melting of sea ice releases molecular chlorine, which reacts with sunlight to produce chlorine atoms. Because chlorine atoms are highly reactive, they can expedite the degradation of methane and tropospheric ozone and the oxidation of mercury to more toxic forms.[19] Cracks in sea ice are causing ozone and mercury uptake in the surrounding environment.[20]

Atmospheric regime

A link has been established between reduced Barents-Kara sea ice and cold winter extremes over northern continents.[21] Model simulation suggest diminished Arctic sea ice may have been a contributing driver of recent wet summers over northern Europe, because of a weakened jet stream, which dives further south.[22] Extreme summer weather in northern mid-latitudes has been linked to a vanishing cryosphere.[23] Evidence suggest that the continued loss of Arctic sea-ice and snow cover may influence weather at lower latitudes. Correlations have been identified between high-latitude cryosphere changes, hemispheric wind patterns and mid-latitude extreme weather events for the Northern Hemisphere.[24] A study from 2004, connected the disappearing sea ice with a reduction of available water in the American west.[25]

Biota

Sea ice decline has been linked to boreal forest decline in North America and is assumed to culminate with an intensifying wildfire regime in this region.[26]

Marine life

The annual net primary production of the Eastern Bering Sea was enhanced by 40–50% through phytoplankton blooms during warm years of early sea ice retreat.[27]

Wildlife

Polar bears are turning to alternate food sources because Arctic sea ice melts earlier and freezes later each year. Polar bears have less time to hunt their historically preferred prey of seal pups and must spend more time on land and hunt other animals.[28] As a result, the diet is less nutritional, which leads to reduced body size and reproduction, thus indicating population decline in polar bears.[29]

See also

- Antarctic sea ice

- Arctic sea ice ecology and history

- Effects of climate change on humans

- Measurement of sea ice

- Polar vortex

- Vanishing Point (2012 film)

References

- ↑ Jennifer E. Kay, Marika M. Holland & Alexandra Jahn (August 22, 2011). "The Physical Science Basis". Geophysical Research Letters. Bibcode:2011GeoRL..3815708K. doi:10.1029/2011GL048008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 IPCC AR5 WG1 (2013). PDF "The Physical Science Basis".

- ↑ J. C. Stroeve, T. Markus, L. Boisvert, J. Miller, A. Barrett (2014). Open Access "Changes in Arctic melt season and implications for sea ice loss". doi:10.1002/2013GL058951.

- ↑ "Daily Updated Time series of Arctic sea ice area and extent derived from SSMI data provided by NERSC". Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Watch 27 years of 'old' Arctic ice melt away in seconds The Guardian 21 February 2014

- ↑ Hannah Hickey (July 29, 2014). "Huge waves measured for first time in Arctic Ocean". University of Washington.

- ↑ http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2013/07/10/1219716110.abstract PNAS

- ↑ http://phys.org/news/2013-08-ice-free-arctic-2050s.html#inlRlv

- ↑ http://www.atmos.pku.edu.cn/yhu/pnas-liu-2013.pdf

- ↑ Overland, J. E.; Wang, M. (2013). "When will the summer Arctic be nearly sea ice free?". Geophysical Research Letters 40 (10): 2097. doi:10.1002/grl.50316.

- ↑ Stroeve, J.; Holland, M. M.; Meier, W.; Scambos, T.; Serreze, M. (2007). "Arctic sea ice decline: Faster than forecast". Geophysical Research Letters 34 (9): L09501. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..3409501S. doi:10.1029/2007GL029703.

- ↑ Holland, M. M.; Bitz, C. M.; Tremblay, B. (2006). "Future abrupt reductions in the summer Arctic sea ice". Geophysical Research Letters 33 (23). doi:10.1029/2006GL028024.

- ↑ Wang, M.; Overland, J. E. (2009). "A sea ice free summer Arctic within 30 years?". Geophysical Research Letters 36 (7). doi:10.1029/2009GL037820.

- ↑ Boé, J.; Hall, A.; Qu, X. (2009). "September sea-ice cover in the Arctic Ocean projected to vanish by 2100". Nature Geoscience 2 (5): 341. Bibcode:2009NatGe...2..341B. doi:10.1038/ngeo467.

- ↑ James E. Overland & Muyin Wang (May 21, 2013). "When will the summer Arctic be nearly sea ice free?". Geophysical Research Letters. doi:10.1002/grl.50316.

- ↑ "Melting Ice Key Message Third National Climate Assessment". National Climate Assessment. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- ↑ Maslowski, Wieslaw (16 March 2010). "Advancements and Limitations in Understanding and Predicting Arctic Climate Change". State of the Arctic (conference website). Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ↑ "US Navy predicts summer ice free Arctic by 2016". The Guardian. 9 December 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ↑ Jin Liao et al.(2013) (January 2014). "High levels of molecular chlorine in the Arctic atmosphere". Nature Geoscience Letter. doi:10.1038/ngeo2046. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ↑ Christopher W. Moore, Daniel Obrist, Alexandra Steffen, Ralf M. Staebler, Thomas A. Douglas, Andreas Richter & Son V. Nghiem (January 2014). "Convective forcing of mercury and ozone in the Arctic boundary layer induced by leads in sea ice". Nature Letter. doi:10.1038/nature12924. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ↑ Vladimir Petoukhov and Vladimir A. Semenov (November 2010). "A link between reduced Barents-Kara sea ice and cold winter extremes over northern continents". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres (1984–2012) 115 (21). Bibcode:2010JGRD..11521111P. doi:10.1029/2009JD013568. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ↑ J A Screen (November 2013). "Influence of Arctic sea ice on European summer precipitation". Environmental Research Letters 8 (4). doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/4/044015. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ↑ Qiuhong Tang, Xuejun Zhang and Jennifer A. Francis (December 2013). "Extreme summer weather in northern mid-latitudes linked to a vanishing cryosphere". Nature Climate Change 4: 45–50. doi:10.1038/nclimate2065. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ↑ James E. Overland (December 2013). "Atmospheric science: Long-range linkage". Nature Climate Change 4 (1): 11–12. doi:10.1038/nclimate2079. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ↑ Jacob O. Sewall, Lisa Cirbus Sloan (2004). "Disappearing Arctic sea ice reduces available water in the American west". Geophysical Research Letters. Bibcode:2004GeoRL..31.6209S. doi:10.1029/2003GL019133.

- ↑ Martin P. Girardin, Xiao Jing Guo, Rogier De Jong, Christophe Kinnard, Pierre Bernier and Frédéric Raulier (December 2013). "Unusual forest growth decline in boreal North America covaries with the retreat of Arctic sea ice". Global Change Biology. doi:10.1111/gcb.12400. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ↑ Zachary W. Brown and Kevin R. Arrigo (January 2013). "Sea ice impacts on spring bloom dynamics and net primary production in the Eastern Bering Sea". Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 118 (1): 43–62. Bibcode:2013JGRC..118...43B. doi:10.1029/2012JC008034. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ↑ Elizabeth Peacock, Mitchell K. Taylor, Jeffrey Laake and Ian Stirling (April 2013). "Population ecology of polar bears in Davis Strait, Canada and Greenland". The Journal of Wildlife Management 77 (3): 463–476. doi:10.1002/jwmg.489. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ↑ Karyn D. Rode, Steven C. Amstrup, and Eric V. Regehr (2010). "Reduced body size and cub recruitment in polar bears associated with sea ice decline". Ecological Applications 20: 768–782. doi:10.1890/08-1036.1. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

External links

- Third National Climate Assessment | Melting Ice

- NASA Earth Observatory | Arctic Sea Ice

- NSIDC | Arctic Sea Ice News

- PIOMAS | Arctic Sea Ice Volume Anomaly

- Wunderground | Arctic Sea Ice Decline

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||