Arctic char

| Arctic char | |

|---|---|

| |

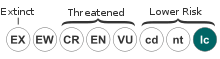

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Salmoniformes |

| Family: | Salmonidae |

| Genus: | Salvelinus |

| Species: | S. alpinus |

| Binomial name | |

| Salvelinus alpinus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

Arctic char or Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) is a cold-water fish in the family Salmonidae, native to alpine lakes and arctic and subarctic coastal waters. It breeds in fresh water, and populations can either be landlocked or anadromous, migrating to the sea.[2] No other freshwater fish is found as far north; it is, for instance, the only fish species in Lake Hazen on Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic. It is one of the rarest fish species in Britain, found only in deep, cold, glacial lakes, and is at risk from acidification. In other parts of its range, such as Scandinavia, it is much more common, and is fished extensively. It is also common in the Alps, (particularly in Trentino and the mountainous part of Lombardy), where it can be found in lakes up to an altitude of 2,600 m (8,500 ft) above sea level, and in Iceland. In Siberia, it is known as golets and it has been introduced in lakes where it sometimes threatens less hardy endemic species, such as the small-mouth char and the long-finned char in Elgygytgyn Lake.

The Arctic char is closely related to both salmon and lake trout, and has many characteristics of both. The fish is highly variable in colour, depending on the time of year and the environmental conditions of the lake where it lives. Individual fish can weigh 20 lb (9.1 kg) or more with record-sized fish having been taken by anglers in northern Canada, where it is known as iqaluk or tariungmiutaq in Inuktitut. Generally, whole market-sized fish are between 2 and 5 lb (0.91 and 2.27 kg). The flesh colour can range from a bright red to a pale pink.

Subspecies

In North America, three subspecies of Salvelinus alpinus exist. S. a. erythrinus is native to almost all of Canada's northern coast. This subspecies is nearly always anadromous. S. a. oquassa, known as the Sunapee trout or the blueback trout, is native to eastern Quebec and northern New England, although it has been extirpated from most of its eastern United States range. S. a. oquassa is never anadromous. Taranets char and the dwarf Arctic char are both classified as S. a. taranetzi.

Arctic char are also found in Lake Pingualuit, a lake formed roughly 1.4 million years ago from an impact crater. Changing water levels are believed to have connected the lake with glacial runoff and surrounding streams and rivers, allowing char to swim upstream into the lake. Arctic char are the only fish found in the lake, and signs of fish cannibalism have been found.[3]

Farming

Research aimed at determining the suitability of Arctic char as a cultured species has been going on since the late 1970s. The Canadian government's Freshwater Institute of Fisheries and Oceans Canada at Winnipeg, Manitoba, and the Huntsman Marine Science Centre of New Brunswick, pioneered the early efforts in Canada. Arctic char are also farmed in Iceland, Estonia, Norway, Sweden, Finland, West Virginia,[4] and Ireland.

Arctic char were first investigated because they were expected to have low optimum temperature requirements and would grow well at the cold water temperatures present in numerous areas of Canada. They could be an alternate species to rainbow trout and could provide producers with a different niche in the marketplace. The initial research efforts concentrated on identifying the culture needs and performance characteristics of the species. The Freshwater Institute was responsible for distributing small numbers of char eggs to producers in Canada; these producers in return helped determine the suitability of char in a commercial setting. Commercial char breeding stocks have now been developed largely from these sources.

In 2006, Monterey Bay Aquarium "Seafood Watch" program added farmed Arctic char as an environmentally sustainable Best Choice for consumers, stating: "Arctic char use only a moderate amount of marine resources for feed. In addition, Arctic char are farmed in land-based, closed systems that minimize the risk of escape into the wild."[5]

As food

Commercial Arctic char typically weigh between 2 and 10 lb (1 and 4.5 kg). The flesh is fine flaked and medium firm. The colour is between light pink and deep red, and the taste is like something between trout and salmon.[6]

Diet

The char diet varies with the seasons. During late spring and summer, they feed on insects found on the water's surface, salmon eggs, snails and other smaller crustaceans found on the lake bottom, and smaller fish up to a third of the char's size. During the autumn and winter months the char feeds on zoo plankton and freshwater shrimps that are suspended in the lake and also occasionally feeds on smaller fish.

Spawning

Spawning takes place from September to November over rocky shoals in lakes with heavy wave action and in slower gravel-bottom pools in rivers. As with most salmonids, vast differences in coloration and body shape occur between sexually mature males and females. Males develop hooked jaws known as kypes and take on a brilliant red colour. Females remain fairly silver. Most males set up and guard territories and often spawn with several females. The female constructs the nest, or redd. A female anadromous char usually deposits from 3,000 to 5,000 eggs. Char do not die after spawning like Pacific salmon and often spawn several times throughout their lives, typically every second or third year. Young char emerge from the gravel in spring and stay in the river from 5 to 7 months or until they are about 6–8 in (15–20 cm) in length.

References

- ↑ J. Freyhof & M. Kottelat (2008). "Salvelinus alpinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ↑ Cambridge Bay Arctic Char at Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- ↑ E. A. Keller, R. H. Blodgett & J. J. Clague (2010). The Catastrophic Earth, Natural Disasters. Pearson Custom Publishing. ISBN 9780536878137.

- ↑ ARC | Mining Fresh Water for Aquaculture

- ↑ Seafood Watch Newsletter, August 2006, Monterey Bay Aquarium, Monterey, California, USA

- ↑ "Chef's Resources - Arctic Char Profile". Chefs-resources.com.

Further reading

- T. A. Dick, C. P. Gallagher & A. Yang (2009). "Summer habitat use of Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) in a small Arctic lake, monitored by acoustic telemetry". Ecology of Freshwater Fish 18 (1): 117–125. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0633.2008.00330.x.

- Hand Nordeng (2009). "Char ecology. Natal homing in sympatric populations of anadromous Arctic char Salvelinus alpinus (L.): roles of pheromone recognition". Ecology of Freshwater Fish 18 (1): 41–51. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0633.2008.00320.x.

- C. P. Gallagher & T. A. Dick (2010). "Trophic structure of a landlocked Arctic char Salvelinus alpinus population from southern Baffin Island, Canada". Ecology of Freshwater Fish 19 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0633.2009.00387.x.

- F. Gregersen, P. Aass, L. A. Vøllestad & J. H. L'Abée-Lund (2006). "Long-term variation in diet of Arctic char, Salvelinus alpinus, and brown trout, Salmo trutta: effects of changes in fish density and food availability". Fisheries Management and Ecology 13 (4): 243–250. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2400.2006.00500.x.

- T. Lyytikainen, J. Koskela & I. Rissanen (1997). "The influence of temperature on growth and proximate body composition of under yearling Lake Inari arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus (L.))". Journal of Applied Ichthyology 13 (4): 191–194. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0426.1997.tb00120.x.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salvelinus alpinus. |

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2005). "Salvelinus alpinus" in FishBase. 10 2005 version.

- Information on farming Arctic char:This site deals with Arctic char and farming the fish using land based farms. Gives a background and description of the species including its aquaculture history.

- Environmental concerns

- Articles presented at the International Conference on the Conservation and Management of Arctic Charr

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||