Arch of Constantine

| Arch of Constantine | |

|---|---|

|

Arch of Constantine | |

| Built in | AD 315 |

| Built by/for | Constantine I |

| Type of structure | Triumphal arch |

| Related |

List of ancient monuments in Rome |

Arch of Constantine | |

The Arch of Constantine (Italian: Arco di Costantino) is a triumphal arch in Rome, situated between the Colosseum and the Palatine Hill. It was erected by the Roman Senate to commemorate Constantine I's victory over Maxentius at the Battle of Milvian Bridge on October 28, 312.[1] Dedicated in 315, it is the latest of the existing triumphal arches in Rome, and the only one to make extensive use of spolia, re-using several major reliefs from 2nd century imperial monuments, which give a striking and famous stylistic contrast to the sculpture newly created for the arch.

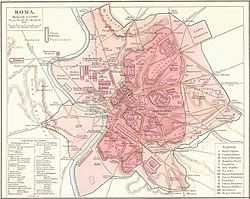

The arch spans the Via Triumphalis, the way taken by the emperors when they entered the city in triumph. This route started at the Campus Martius, led through the Circus Maximus, and around the Palatine Hill; immediately after the Arch of Constantine, the procession would turn left at the Meta Sudans and march along the Via Sacra to the Forum Romanum and on to the Capitoline Hill, passing both the Arches of Titus and Septimius Severus.

General description

|

|

The arch is 21 m high, 25.9 m wide and 7.4 m deep. It has three archways, the central one being 11.5 m high and 6.5 m wide, the lateral archways 7.4 m by 3.4 m each. The top (called attic) is brickwork reveted with marble. A staircase formed in the thickness of the arch is entered from a door at some height from the ground, in the end towards the Palatine Hill.

The general design with a main part structured by detached columns and an attic with the main inscription above is modelled after the example of the Arch of Septimius Severus on the Roman Forum. It has been suggested that the lower part of the arch is re-used from an older monument, probably from the times of the emperor Hadrian (Conforto et al., 2001; for a defence of the view that the whole arch was constructed in the 4th century, see Pensabene & Panella).

During the Middle Ages, the Arch of Constantine was incorporated into one of the family strongholds of ancient Rome. Works of restoration were first carried out in the 18th century; the last excavations have taken place in the late 1990s, just before the Great Jubilee of 2000.

The arch served as the finish line for the marathon athletic event for the 1960 Summer Olympics.

Sculptural style

The arch is a famous exemplar, almost invariably cited in surveys of art history, of the stylistic changes of the 4th century, and the "collapse of the classical Greek canon of forms during the late Roman period".[3] The contrast between the styles of the re-used Imperial reliefs of Trajan, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius and those newly made for the arch is dramatic and, according to Ernst Kitzinger, "violent",[3] although it should be noted that where the head of an earlier emperor was replaced by that of Constantine the artist was still able to achieve a "soft, delicate rendering of the face of Constantine" that was "a far cry from the dominant style of the workshop".[4]

Kitzinger compares a roundel of Hadrian lion-hunting, which is "still rooted firmly in the tradition of late Hellenistic art", and there is "an illusion of open, airy space in which figures move freely and with relaxed self-assurance" with the later frieze where the figures are "pressed, trapped, as it were, between two imaginary planes and so tightly packed within the frame as to lack all freedom of movement in any direction", with "gestures that are "jerky, overemphatic and uncoordinated with the rest of the body".[3] In the 4th century reliefs, the figures are disposed geometrically in a pattern that "makes sense only in relation to the spectator", in the largesse scene (below) centred on the emperor who looks directly out to the viewer. Kitzinger continues: "Gone too is the classical canon of proportions. Heads are disproportionately large, trunks square, legs stubby ... "Differences in the physical size of figures drastically underline differences of rank and importance which the second-century artist had indicated by subtle compositional means within a seemingly casual grouping. Gone, finally are elaboration of detail and differentiation of surface texture. Faces are cut rather than modelled, hair takes the form of a cap with some superficial stippling, drapery folds are summarily indicated by deeply drilled lines."[5]

The commission was clearly highly important, if hurried, and the work must be considered as reflecting the best available craftsmanship in Rome at the time; the same workshop was probably responsible for a number of surviving sarcophagi.[5] The question of how to account for what may seem a decline in both style and execution has generated a vast amount of discussion. Factors introduced into the discussion include: a breakdown of the transmission in artistic skills due to the political and economic disruption of the Crisis of the Third Century,[6] influence from Eastern and other pre-classical regional styles from around the Empire (a view promoted by Josef Strzygowski (1862-1941), and now mostly discounted),[7] the emergence into high-status public art of a simpler "popular" or "Italic" style that had been used by the less wealthy throughout the reign of Greek models, an active ideological turning against what classical styles had come to represent, and a deliberate preference for seeing the world simply and exploiting the expressive possibilities that a simpler style gave.[8] One factor that cannot be responsible, as the date and origin of the Venice Portrait of the Four Tetrarchs show, is the rise of Christianity to official support, as the changes predated that.[9]

Iconography

The arch is heavily decorated with parts of older monuments, which assume a new meaning in the context of the Constantinian building. As it celebrates the victory of Constantine, the new "historic" friezes illustrating his campaign in Italy convey the central meaning: the praise of the emperor, both in battle and in his civilian duties. The other imagery supports this purpose: decoration taken from the "golden times" of the Empire under the 2nd century emperors whose reliefs were re-used places Constantine next to these "good emperors", and the content of the pieces evokes images of the victorious and pious ruler.

Another explanation given for the re-use is the short time between the start of construction (late 312 at the earliest) and the dedication (summer 315), so the architects used existing artwork to make up for the lack of time to create new art. As yet another possible reason, it has often been suggested that the Romans of the 4th century lacked the artistic skill to produce acceptable artwork and therefore plundered the ancient buildings to adorn their contemporary monuments. This interpretation has become less prominent in more recent times, as the art of Late Antiquity has been appreciated in its own right. It is possible that a combination of those explanations is correct.[10]

Attic

Above the middle archway, the main inscription takes the most prominent place of the attic. It is identical on both sides of the arch.

Flanking the inscription on both sides are pairs of relief panels above the minor archways, being eight total. They were taken from an unknown monument erected in honour of Marcus Aurelius, and show (north side, left to right) the emperor's return to Rome after the campaign (adventus), the emperor leaving the city and saluted by a personification of the Via Flaminia, the emperor distributing money among the people (largitio), the emperor interrogating a German prisoner, (south side, left to right) a captured enemy chieftain led before the emperor, a similar scene with other prisoners, the emperor speaking to the troops (adlocutio), and the emperor sacrificing pig, sheep and bull (suovetaurilia). Together with three panels now in the Capitoline Museum, the reliefs were probably taken from a triumphal monument commemorating Marcus Aurelius' war against the Marcomanni and the Sarmatians from 169 – 175, which ended with his triumphant return in 176. On the largitio panel, the figure of Marcus Aurelius' son Commodus has been eradicated after the latter's damnatio memoriae.

From the same time date the two large (3 m high) panels decorating the attic on the small sides of the arch, showing scenes from the emperor's Dacian Wars. Together with the two reliefs on the inside of the central archway, they came from a large frieze celebrating the Dacian victory. The original place of this frieze was either the Forum of Trajan, as well, or the barracks of the emperor's horse guard on the Caelius.

Main section

The general layout of the main facade is identical on both sides of the arch. It is divided by four columns of Corinthian order made of Numidian yellow marble (giallo antico), one of which has been transferred into the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano and was replaced by a white marble column. The columns stand on bases showing victory figures on front, and captured barbarians and Roman soldiers on the sides.

The spandrels of the main archway are decorated with reliefs depicting victory figures with trophies, those of the smaller archways show river gods. Column bases and spandrel reliefs are from the times of Constantine.

Above each lateral archway are pairs of round reliefs dated to the times of Emperor Hadrian. They display scenes of hunting and sacrificing: (north side, left to right) hunt of a boar, sacrifice to Apollo, hunt of a lion, sacrifice to Hercules, (south side, left to right) departure for the hunt, sacrifice to Silvanus, hunt of a bear, sacrifice to Diana. The head of the emperor (originally Hadrian) has been reworked in all medallions: on the north side, into Constantine in the hunting scenes and into Licinius or Constantius I in the sacrifice scenes; on the south side, vice versa. The reliefs, c. 2 m in diameter, were framed in porphyry; this framing is only extant on the right side of the northern facade. Similar medallions, of Constantinian origin, are located on the small sides of the arch; the eastern side shows the Sun rising, on the western side, the Moon. Both are on chariots.

The main piece from the time of Constantine is the "historical" relief frieze running around the monument under the round panels, one strip above each lateral archway and at the small sides of the arch. These reliefs depict scenes from the Italian campaign of Constantine against Maxentius which was the reason for the construction of the monument. The frieze starts at the western side with the "Departure from Milan". It continues on the southern, "outward" looking face, with the siege of Verona, which was of great importance to the war in Northern Italy; also on that face, the Battle of Milvian Bridge with Constantine's army victorious and the enemy drowning in the river Tiber. On the eastern side, Constantine and his army enter Rome; the artist seems to have avoided using imagery of the triumph, as Constantine probably did not want to be shown triumphant over the Eternal City. On the northern face, looking "towards" the city, two strips with the emperor's actions after taking possession of Rome: Constantine speaking to the citizens on the Forum Romanum, and distributing money to the people. On the top side of the Arch of Constantine, large sculptures representing Dacians can be seen.

Inner sides of the archways

In the central archway, there is one large panel of Trajan's Dacian War on each wall. Inside the lateral archways are eight portraits busts (two on each wall), destroyed to such an extent that it is no longer possible to identify them.

Inscriptions

The main inscription would originally have been of bronze letters. It can still be read easily; only the recesses in which the letters sat, and their attachment holes, remain. It reads thus, identically on both sides:

- IMP · CAES · FL · CONSTANTINO · MAXIMO · P · F · AVGUSTO · S · P · Q · R · QVOD · INSTINCTV · DIVINITATIS · MENTIS · MAGNITVDINE · CVM · EXERCITV · SVO · TAM · DE · TYRANNO · QVAM · DE · OMNI · EIVS · FACTIONE · VNO · TEMPORE · IVSTIS · REMPVBLICAM · VLTVS · EST · ARMIS · ARCVM · TRIVMPHIS · INSIGNEM · DICAVIT

- To the Emperor Caesar Flavius Constantinus, the greatest, pious, and blessed Augustus: because he, inspired by the divine, and by the greatness of his mind, has delivered the state from the tyrant and all of his followers at the same time, with his army and just force of arms, the Senate and People of Rome have dedicated this arch, decorated with triumphs.

The words instinctu divinitatis ("inspired by the divine") have been greatly commented on. They are usually read as sign of Constantine's shifting religious affiliation: The Christian tradition, most notably Lactantius and Eusebius of Caesarea, relate the story of a vision of God to Constantine during the campaign, and that he was victorious in the sign of the cross at the Milvian Bridge. The official documents (esp. coins) still prominently display the Sun god until 324, while Constantine started to support the Christian church from 312 on. In this situation, the vague wording of the inscription can be seen as the attempt to please all possible readers, being deliberately ambiguous, and acceptable to both pagans and Christians. As was customary, the vanquished enemy is not mentioned by name, but only referred to as "the tyrant", drawing on the notion of the rightful killing of a tyrannical ruler; together with the image of the "just war", it serves as justification of Constantine's civil war against Maxentius.

Two short inscriptions on the inside of the central archway transport a similar message: Constantine came not as conqueror, but freed Rome from occupation:

- LIBERATORI VRBIS (liberator of the city) — FUNDATORI QVIETIS (founder of peace)

Over each of the small archways, inscriptions read:

- VOTIS X — VOTIS X

- SIC X — SIC XX

They give a hint on the date of the arch: "Solemn vows for the 10th anniversary – for the 20th anniversary" and "as for the 10th, so for the 20th anniversary". Both refer to Constantine's decennalia, i.e. the 10th anniversary of his reign (counted from 306), which he celebrated in Rome in the summer of 315. It can be assumed that the arch honouring his victory was inaugurated during his stay in the city.

Works modeled on, or inspired by, the Arch of Constantine

- Brandenburg Gate, Potsdam, Prussia (1770)

- Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, Paris, France (1806)

- Marble Arch, London, England (1828)

- Siegestor, Munich, Germany

- Union Station, Washington, D.C., USA (1908)

- American Museum of Natural History (Central Park West facade), New York City, USA (1936)

- Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire, UK

References and sources

- References

- ↑ By the "Senate and people" (S.P.Q.R.) according to the inscription, though the Emperor may have "suggested". See also: A. L. Frothingham. "Who Built the Arch of Constantine? III." The Attic, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 19, No. 1. (Jan. - Mar., 1915), pp. 1-12

- ↑ "Arch of Constantine". smARThistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Kitzinger, 7

- ↑ Kitzinger, 29

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kitzinger, 8

- ↑ Kitzinger, 8-9

- ↑ Kitzinger, 9-12

- ↑ Kitzinger, 10-18

- ↑ Kitzinger, 5-6, 9, 19

- ↑ Kitzinger, 8-15

- Sources

- Kitzinger, Ernst, Byzantine art in the making: main lines of stylistic development in Mediterranean art, 3rd-7th century, 1977, Faber & Faber, ISBN 0571111548 (US: Cambridge UP, 1977)

- Maria Letizia Conforto et al., Adriano e Costantino. Le due fasi dell'arco nella Valle del Colosseo, Milan, 2002, (in Italian)

- Patrizio Pensabene and Clementina Panella, Arco di Costantino: tra archeologia e archeometria, Rome 1999 (in Italian)

Further reading

- Sydney Dean, Editor. Journal of American Archaeology. July–December, 1920. (Archaeological News reports that in Bulletino della Commissione archeologica comunale di Roma, C. Gradara published an excerpt for the diary of Pietro Bracci in which Bracci states that he carved new heads for the emperors and other figures in the attic reliefs, along with new heads and hands for seven of the Dacian captives and one completely new Dacian.)

- Inez Scott Ryberg. Panel Reliefs of Marcus Aurelius (Monographs on archaeology and the fine arts, 14) 1967. ASIN: B0006BQ1JW

- Eric Varner. Mutilation and Transformation. Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2004. ISBN 90-04-13577-4.

- Mark Wilson Jones. "Genesis and Mimesis: The Design of the Arch of Constantine in Rome." The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 59, No. 1. (Mar., 2000), pp. 50–77.

- H. Stuart Jones "The Relief Medallions of the Arch of Constantine," Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. III. MacMillan & Co., 1906. pp. 216–271.

- M Bieber. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archaeologischen Instituts, Roemische Abteilung. 1911, p. 214.

- H. P. L'Orange; A. von Gerkan. Der Spatantike Bildschmuck des Konstantinsbogens 1939. ISBN 3110022494

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality : late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 58, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arch of Constantine. |

- 1960 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. p. 80.

- 1960 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 2, Part 1. p. 118.

- The Arch of Constantine, a detailed article "for scholars and enthusiasts"

- Inscriptions illustrated and discussed

- Google Maps satellite image

- Guided tour of the Arch of Constantine on Roma Interactive

Coordinates: 41°53′23″N 12°29′27″E / 41.88972°N 12.49083°E

| ||||||

| ||||||||