Arawakan languages

| Arawakan | |

|---|---|

| Maipurean | |

| Geographic distribution: | From every country in South America, except Ecuador, Uruguay and Chile, to Central America and the Caribbean (migration path) |

| Linguistic classification: |

|

| Subdivisions: |

|

| ISO 639-5: | awd |

| Glottolog: | araw1281[1] |

|

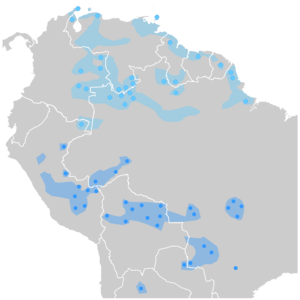

Maipurean languages in South America (Caribbean and Central America not included): North-Maipurean (clear blue) and South-Maipurean (dark blue). Spots represent location of extant languages, and shadowed areas show probable earlier locations. | |

Arawakan (Arahuacan, Maipuran Arawakan, "mainstream" Arawakan, Arawakan proper), also known as Maipurean (also Maipuran, Maipureano, Maipúre), is a language family that developed among ancient indigenous peoples in South America. Branches migrated to Central America and the Greater Antilles in the Caribbean and the Atlantic, including what is now called the Bahamas. Only present-day Ecuador, Uruguay and Chile did not have peoples who spoke Arawakan languages. Maipurean may be related to other language families in a hypothetical Macro-Arawakan stock.

The name Maipure was given to the family by Filippo S. Gilij in 1782, after the Maipure language of Venezuela, which he used as a basis of his comparisons. It was renamed after the culturally more important Arawak language a century later. The term Arawak took over, until its use was extended by North American scholars to the broader Macro-Arawakan proposal. At that time, the name Maipurean was resurrected for the core family. See Arawakan vs Maipurean for details.

Languages

The classification of Maipurean is difficult due to the large number of Arawakan languages that are extinct and poorly documented. However, apart from transparent relationships that might constitute single languages, several groups of Maipurean languages are generally accepted by scholars. Many classifications agree in dividing Maipurean into northern and southern branches, though perhaps not all languages fit into one or the other. The three classifications below all accept:

- Ta-Maipurean = Caribbean Arawak / Ta-Arawak = Caribbean Maipuran,

- Upper Amazon Maipurean = North Amazonian Arawak = Inland Maipuran,

- Central Maipurean = Pareci–Xingu = Paresí–Waurá = Central Maipuran,

- Piro = Purus,

- Campa = Pre-Andean Maipurean = Pre-Andine Maipuran.

An early contrast between Ta-Arawak and Nu-Arawak, depending on the prefix for "I", is spurious; nu- is the ancestral form for the entire family, whereas ta- is an innovation of one branch of the family.

Kaufman (1994)

The following (tentative) classification is from Kaufman (1994: 57-60). Details of established branches are given in the linked articles. In addition to the family tree detailed below, there are a few languages that are "Non-Maipurean Arawakan languages or too scantily known to classify" (Kaufman 1994: 58), which include:

Another language is also mentioned as "Arawakan":

- Salumã (AKA Salumán, Enawené-Nawé)

Including these unclassified languages mentioned above, the Maipurean family has about 64 languages. Out of these, 29 languages are now extinct: Wainumá, Mariaté, Anauyá, Amarizana, Jumana, Pasé, Cawishana, Garú, Marawá, Guinao, Yavitero, Maipure, Manao, Kariaí, Waraikú, Yabaána, Wiriná, Aruán, Taíno, Kalhíphona, Marawán-Karipurá, Saraveca, Custenau, Inapari, Kanamaré, Shebaye, Lapachu, and Morique.

- Northern Maipurean

- Upper Amazon branch

- Maritime branch

- Southern Maipurean

- Western branch

- Amuesha (AKA Amoesha, Yanesha’)

- Chamicuro (AKA Chamikuro)

- Central branch

- Southern Outlier branch

- Campa branch (also known Pre-Andean)

Aikhenvald (1999)

Apart from minor decisions on whether a variety is a language or a dialect, changing names, and not addressing several poorly attested languages, Aikhenvald departs from Kaufman in breaking up the Southern Outlier and Western branches of Southern Maipurean. She assigns Salumã and Lapachu ('Apolista') to what is left of Southern Outlier ('South Arawak'); breaks up the Maritime branch of Northern Maipurean, though keeping Aruán and Palikur together; and is agnostic about the sub-grouping of the North Amazonian branch of Northern Maipurean.

The following breakdown uses Aikhenvald's nomenclature followed by Kaufman's:

- North Arawak = Northern Maipurean

- Rio Branco = Kaufman's Wapishanan (2) [but with Mapidian as a separate language]

- Palikur = Kaufman's Palikur + Aruán (3)

- Caribbean = Ta-Maipurean (8) [incl. Shebaye]

- North Amazonian = Upper Amazon (17 attested)

- South and South-Western Arawak = Southern Maipurean

- South Arawak = Terena + Kaufman's Moxos group + Salumã + Lapachu ['Apolista'] (11)

- Pareci–Xingu = Central Maipurean (6)

- South-Western Arawak = Piro (5)

- Campa (6)

- Amuesha (1)

- Chamicuro (1)

Aikhenvald classifies Kaufman's unclassified languages apart from Morique. She does not classify 15 extinct languages which Kaufman had placed in various branches of Maipurean.

In addition Mawayana, mistaken for Mapidian in earlier sources, is evidently a distinct language.

Walker & Ribeiro (2011)

Walker & Ribeiro (2011),[2] using Bayesian computational phylogenetics, classify the Arawakan languages as follows.

| Arawakan |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

The internal structures of each branch is given below. Note that the strictly binary splits are a result of the Bayesian computational methods used.

- Circum-Caribbean

- Central Brazil

- (branch)

- (branch)

- Yawalapití

- Waurá, Mehináku

- Central Amazonia

- Northwest Amazonia

Arawakan vs. Maipurean

In 1783, the Italian priest Filippo Gilii recognized the unity of the Maipure language of the Orinoco and Moxos of Bolivia; he named their family Maipure. It was renamed Arawak by Von den Steinen (1886) and Brinten (1891) after Arawak in the Guianas, one of the major languages of the family. The modern equivalents are Maipurean or Maipuran and Arawak or Arawakan.

The term Arawakan is now used in two senses. South American scholars use Aruák for the family demonstrated by Gilij and subsequent linguists. In North America, however, scholars have used the term to include a hypothesis adding the Guajiboan and Arawan families. In North America, scholars use the name Maipurean to distinguish the core family, which is sometimes called core Arawak(an) or Arawak(an) proper instead.[3]

Kaufman (1990: 40) relates the following:

[The Arawakan] name is the one normally applied to what is here called Maipurean. Maipurean used to be thought to be a major subgroup of Arawakan, but all the living Arawakan languages, at least, seem to need to be subgrouped with languages already found within Maipurean as commonly defined. The sorting out of the labels Maipurean and Arawakan will have to await a more sophisticated classification of the languages in question than is possible at the present state of comparative studies.

Characteristics

The languages called Arawakan or Maipuran were originally recognized as a separate group in the late nineteenth century. Almost all the languages now called Arawakan share a first-person singular prefix nu-, but Arawak proper has ta-. Other commonalities include a second-person singular pi-, relative ka-, and negative ma-.

The Arawak language family, as constituted by L. Adam, at first by the name of Maypure, has been called by Von den Steinen "Nu-Arawak" from the prenominal prefix "nu-" for the first person. This is common to all the Arawak tribes scattered along the coasts from Dutch Guiana to British Guiana.

Upper Paraguay has Arawakan-language tribes: the Quinquinaos, the Layanas, etc. (This is the Moho-Mbaure group of L. Quevedo). In the islands of Marajos, in the middle of the estuary of the Amazon, the Aruan people spoke an Arawak dialect. The peninsula of Goajira (north of Venezuela) is occupied by the Goajires tribe, also Arawakan speakers. In 1890–95, De Brette estimated a population of 3,000 persons in the Goajires.[4]

C. H. de Goeje's published vocabulary of 1928 outlines the Lokono/Arawak (Dutch and Guiana) 1400 items, mostly morphemes (stems, affixes) and morpheme partials (single sounds) – rarely compounded, derived, or otherwise complex sequences; and from Nancy P. Hickerson's British Guiana manuscript vocabulary of 500 items. However, most entries which reflect acculturation are direct borrowings from one or another of three model languages (Spanish, Dutch, English). Of the 1400 entries in de Goeje, 106 reflect European contact; 98 of these are loans. Nouns which occur with the verbalizing suffix described above number 9 out of the 98 loans.[5]

Some examples

The Arawak word for maize is marisi, and various forms of this word are found among the related tribal languages:

- Arawak, marisi, Guiana.

- Cauixana, mazy, Rio Jupura.

- Goajiro, maique, Goajiros Peninsula.

- Passes, mary, Lower Jupura.

- Puri, maky, Rio Paraiba.

- Wauja, mainki, Upper Xingu River.

Linguists could trace that the Caribs borrowed their word for maize from the Arawaks, for the Arawak radical is used by the females of that tribe; the males use a different noun.[6]

Geographic distribution

Arawak is the largest family in the Americas with the respect to number of languages (also including much internal branching) and covers the widest geographical area of any language group in Latin America. The Arawakan languages have been spoken by peoples occupying a large swath of territory, from the eastern slopes of the central Andes Mountains in Peru and Bolivia, across the Amazon basin of Brazil, southward into Paraguay and northward into Suriname, Guyana, Venezuela, and Colombia on the northern coast of South America, and as far north as Belize and Guatemala. Arawak-speaking peoples migrated to islands in the Caribbean, settling the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas. It is possible that some poorly attested extinct languages in North America, such as the Cusabo and Congaree in South Carolina, were members of this family.

Taíno, commonly called Island Arawak, was spoken on the islands of Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and the Bahamas. A few Taino words are still used by English or Spanish-speaking descendants in these islands. The Taíno language was scantily attested but its classification within the Arawakan family is uncontroversial. Its closest relative among the better attested Arawakan languages seems to be the Goajiro language, spoken in Colombia. Scholars have suggested that the Goajiro are descended from Taíno refugees, but the theory seems impossible to prove or disprove.

Among the Arawakan peoples were the Carib, after whom the Caribbean was named, who formerly lived throughout the Lesser Antilles. In the seventeenth century, the language of the Island Carib was described by European missionaries as two separate, unrelated languages—one spoken by the men of the society and the other by the women. The language spoken by the men, which they called Carib, was very similar to the Galibi language spoken in what later became French Guyana. At the time, the missionaries thought it was not part of Arawakan, which they identified the women as speaking. This unique dual gender-specific language arrangement was unstable and dynamic and cannot have been very old. Scholars think it suggests that the male Carib speakers had recently migrated north into the Lesser Antilles at the time of European contact, displacing or assimilating the male Arawaks in the process.

The Island Carib language is now extinct, although Carib people still live on Dominica, Trinidad, St. Lucia and St. Vincent. Despite its name, Island Carib was an Arawak language. Its derived modern language, Garífuna (or Black Carib), is also Arawak and was developed among mixed-race African-Carib peoples. It is estimated to have about 590,000 speakers in Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala and Belize. The Garifuna are the descendants of Caribs and escaped slaves of African origin, transferred by the British from Saint Vincent to islands in the Bay of Honduras in 1796. The Garifuna language is derived from the women's Arawak-based Island Carib language and only a few traces remain of the men's Carib speech.

Today the Arawakan languages with the most speakers are among the more recent Ta-Arawakan (Ta-Maipurean) groups: Wayuu [Goajiro], with about 300,000 speakers; and Garífuna [Black Carib], with about 100,000 speakers. The Campa group is next; Asháninca or Campa proper has 15–18,000 speakers; and Ashéninca 18–25,000. After that probably comes Terêna, with 10,000 speakers; and Yanesha' [Amuesha] with 6–8,000.

See also

- Arawak peoples

- English words of Arawakan origin

Further reading

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. (1999). The Arawak language family. In R. M. W. Dixon & A. Y. Aikhenvald (Eds.), The Amazonian languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57021-2; ISBN 0-521-57893-0.

- Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- Derbyshire, Desmond C. (1992). Arawakan languages. In W. Bright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of linguistics (Vol. 1, pp. 102–105). New Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kaufman, Terrence. (1990). Language history in South America: What we know and how to know more. In D. L. Payne (Ed.), Amazonian linguistics: Studies in lowland South American languages (pp. 13–67). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70414-3.

- Kaufman, Terrence. (1994). The native languages of South America. In C. Mosley & R. E. Asher (Eds.), Atlas of the world's languages (pp. 46–76). London: Routledge.

- Migliazza, Ernest C.; & Campbell, Lyle. (1988). Panorama general de las lenguas indígenas en América (pp. 223). Historia general de América (Vol. 10). Caracas: Instituto Panamericano de Geografía e Historia.

- Payne, David. (1991). A classification of Maipuran (Arawakan) languages based on shared lexical retentions. In D. C. Derbyshire & G. K. Pullum (Eds.), Handbook of Amazonian languages (Vol. 3, pp. 355–499). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Solís Fonseca, Gustavo. (2003). Lenguas en la amazonía peruana. Lima: edición por demanda.

- Zamponi, Raoul. (2003). Maipure, Munich: Lincom Europa. ISBN 3-89586-232-0.

References

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Arawakan". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Walker, R. S., & Ribeiro, L. A. (2011). "Bayesian phylogeography of the Arawak expansion in lowland South America." Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 278(1718), 2562-2567.

- ↑ Aikhenvald (1999:73)

- ↑ Deniker, Joseph. (1900). The races of man: an outline of anthropology and ethnography., pp. 556–557

- ↑ de Goeje, C. H., (1928). The Arawak language of Guiana, Verhandelingen der Koninkljke Akademie van Wetenshappen te Amserdam, Ajdeiling Letterkunde, Nieuwe Reeks 28: 2.

- ↑ Arboretum, Morris., (1893). Contributions from the Botanical Laboratory of the University of ..., Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania – Botanical Laboratory, pp. 128, 156

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||