Apricot

An apricot is a fruit or the tree that bears the fruit. Usually, an apricot tree is from the tree species Prunus armeniaca, but the species Prunus brigantina, Prunus mandshurica, Prunus mume, and Prunus sibirica are closely related, have similar fruit, and are also called apricots.[1]

Description

The apricot is a small tree, 8–12 m (26–39 ft) tall, with a trunk up to 40 cm (16 in) in diameter and a dense, spreading canopy. The leaves are ovate, 5–9 cm (2.0–3.5 in) long and 4–8 cm (1.6–3.1 in) wide, with a rounded base, a pointed tip and a finely serrated margin. The flowers are 2–4.5 cm (0.8–1.8 in) in diameter, with five white to pinkish petals; they are produced singly or in pairs in early spring before the leaves. The fruit is a drupe similar to a small peach, 1.5–2.5 cm (0.6–1.0 in) diameter (larger in some modern cultivars), from yellow to orange, often tinged red on the side most exposed to the sun; its surface can be smooth (botanically described as: glabrous) or velvety with very short hairs (botanically: pubescent). The flesh is usually firm and not very juicy. Its taste can range from sweet to tart. The single seed is enclosed in a hard, stony shell, often called a "stone", with a grainy, smooth texture except for three ridges running down one side.[2][3]

Cultivation and uses

History of cultivation

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 201 kJ (48 kcal) |

|

11 g | |

| Sugars | 9 g |

| Dietary fiber | 2 g |

|

0.4 g | |

|

1.4 g | |

| Vitamins | |

| Vitamin A equiv. beta-carotene |

(12%) 96 μg (10%) 1094 μg89 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) |

(3%) 0.03 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

(3%) 0.04 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

(4%) 0.6 mg |

|

(5%) 0.24 mg | |

| Vitamin B6 |

(4%) 0.054 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

(2%) 9 μg |

| Vitamin C |

(12%) 10 mg |

| Vitamin E |

(6%) 0.89 mg |

| Vitamin K |

(3%) 3.3 μg |

| Trace metals | |

| Calcium |

(1%) 13 mg |

| Iron |

(3%) 0.4 mg |

| Magnesium |

(3%) 10 mg |

| Manganese |

(4%) 0.077 mg |

| Phosphorus |

(3%) 23 mg |

| Potassium |

(6%) 259 mg |

| Sodium |

(0%) 1 mg |

| Zinc |

(2%) 0.2 mg |

|

| |

| |

|

Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,009 kJ (241 kcal) |

|

63 g | |

| Sugars | 53 g |

| Dietary fibre | 7 g |

|

0.5 g | |

|

3.4 g | |

| Vitamins | |

| Vitamin A equiv. beta-carotene |

(23%) 180 μg (20%) 2163 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) |

(1%) 0.015 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

(6%) 0.074 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

(17%) 2.589 mg |

|

(10%) 0.516 mg | |

| Vitamin B6 |

(11%) 0.143 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

(3%) 10 μg |

| Vitamin C |

(1%) 1 mg |

| Vitamin E |

(29%) 4.33 mg |

| Vitamin K |

(3%) 3.1 μg |

| Trace metals | |

| Calcium |

(6%) 55 mg |

| Iron |

(20%) 2.66 mg |

| Magnesium |

(9%) 32 mg |

| Manganese |

(11%) 0.235 mg |

| Phosphorus |

(10%) 71 mg |

| Potassium |

(25%) 1162 mg |

| Sodium |

(1%) 10 mg |

| Zinc |

(3%) 0.29 mg |

|

| |

| |

|

Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

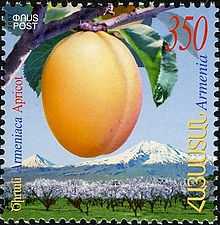

The origin of the apricot is disputed. It was known in Armenia during ancient times, and has been cultivated there for so long that it is often thought to have originated there.[4][5] Its scientific name Prunus armeniaca (Armenian plum) derives from that assumption. For example, the Belgian arborist baron de Poerderlé, writing in the 1770s, asserted, "Cet arbre tire son nom de l'Arménie, province d'Asie, d'où il est originaire et d'où il fut porté en Europe ..." ("this tree takes its name from Armenia, province of Asia, where it is native, and whence it was brought to Europe ...").[6] An archaeological excavation at Garni in Armenia found apricot seeds in an Eneolithic-era site.[7] Despite the great number of varieties of apricots that are grown in Armenia today (about 50),[5] according to the Soviet botanist Nikolai Vavilov its center of origin would be the Chinese region, where the domestication of apricot would have taken place. Other sources say that the apricot was first cultivated in India in about 3000 BC.[8]

Its introduction to Greece is attributed to Alexander the Great;[8] later, the Roman General Lucullus (106–57 BC) also would have imported some trees – the cherry, white heart cherry, and apricot – from Armenia to Rome. Subsequent sources were often confused about the origin of the species. John Claudius Loudon (1838) believed it had a wide native range including Armenia, the Caucasus, the Himalayas, China, and Japan.[9]

Apricots have been cultivated in Persia since antiquity, and dried ones were an important commodity on Persian trade routes. Apricots remain an important fruit in modern-day Iran, where they are known under the common name of zard-ālū (Persian: زردآلو).

Egyptians usually dry apricots, add sweetener, and then use them to make a drink called amar al-dīn.

In the 17th century, English settlers brought the apricot to the English colonies in the New World. Most of modern American production of apricots comes from the seedlings carried to the west coast by Spanish missionaries. Almost all U.S. commercial production is in California, with some in Washington and Utah.[10]

Many apricots are also cultivated in Australia, particularly South Australia, where they are commonly grown in the region known as the Riverland and round the small town of Mypolonga in the Lower Murray region of the state. In states other than South Australia, apricots are still grown, particularly in Tasmania and western Victoria and southwest New South Wales, but they are less common than in South Australia.

Today, apricot cultivation has spread to all parts of the globe with climates that support it.

Cultivation

Although the apricot is native to a continental climate region with cold winters, it can grow in Mediterranean climates if enough cool winter weather allows a proper dormancy. A dry climate is good for fruit maturation. The tree is slightly more cold-hardy than the peach, tolerating winter temperatures as cold as −30 °C (−22 °F) or lower if healthy. A limiting factor in apricot culture is spring frosts: They tend to flower very early (in early March in western Europe), meaning spring frost can kill the flowers. Furthermore, the trees are sensitive to temperature changes during the winter season. In China, winters can be very cold, but temperatures tend to be more stable than in Europe and especially North America, where large temperature swings can occur in winter. Hybridisation with the closely related Prunus sibirica (Siberian apricot; hardy to −50 °C (−58 °F) but with less palatable fruit) offers options for breeding more cold-tolerant plants.[11]

Apricot cultivars are most often grafted onto plum or peach rootstocks. The scion from an existing apricot plant provides the fruit characteristics, such as flavour and size, but the rootstock provides the growth characteristics of the plant.

Cultivators have created what is known as a "black apricot" or "purple apricot", (Prunus dasycarpa), a hybrid of an apricot and the cherry plum (Prunus cerasifera). Other apricot–plum hybrids are variously called plumcots, apriplums, pluots, or apriums.

Apricots have a chilling requirement of 300 to 900 chilling units. They are hardy in USDA zones 5 through 8. Some of the more popular US cultivars of apricots include 'Blenheim', 'Wenatchee Moorpark', 'Tilton', and 'Perfection'.

An old adage says an apricot tree will not grow far from the mother tree; the implication is that apricots are particular about the soil conditions in which they are grown. They prefer well-drained soils with a pH of 6.0 to 7.0. Some apricot cultivars are self-compatible and do not require pollinizer trees; others are not:Moongold and Sungold, for example, must be planted in pairs so that they can pollinate each other.

Apricots are susceptible to numerous diseases whose relative importance is different in the major production regions as a consequence of their climatic differences. Diseases include bacterial canker and blast, bacterial spot and crown gall, and an even longer list of fungal diseases, including brown rot, black knot, Alternaria spot and fruit rot, and powdery mildew. Other problems for apricots are nematodes and viral and phytoplasma diseases, including graft-transmissible problems.

Kernels

Seeds or kernels of the apricot grown in central Asia and around the Mediterranean are so sweet, they may be substituted for almonds. The Italian liqueur amaretto and amaretti biscotti are flavoured with extract of apricot kernels rather than almonds. Oil pressed from these cultivar kernels, and known as oil of almond, has been used as cooking oil. Kernels contain between 2.05% and 2.40% hydrogen cyanide, but normal consumption is insufficient to produce serious effects.[12]

Dried apricots

Dried apricots are a type of traditional dried fruit. When treated with sulfur dioxide (E220), the color is vivid orange. Organic fruit not treated with sulfur vapor is darker in color and has a coarser texture. The world's largest producer of dried apricots is Turkey.[13]

Medicinal and nonfood uses

Cyanogenic glycosides (found in most stone fruit seeds, bark, and leaves) are found in high concentration in apricot seeds. Laetrile, a purported alternative treatment for cancer, is extracted from apricot seeds. Apricot seeds were used against tumors as early as AD 502. In England during the 17th century, apricot oil was also used against tumors, swellings, and ulcers.[14]

A 2011 systematic review of amygdalin from the Cochrane Collaboration found:

The claims that laetrile or amygdalin have beneficial effects for cancer patients are not currently supported by sound clinical data. There is a considerable risk of serious adverse effects from cyanide poisoning after laetrile or amygdalin, especially after oral ingestion. The risk–benefit balance of laetrile or amygdalin as a treatment for cancer is therefore unambiguously negative.[15]

In Europe, apricots were long considered an aphrodisiac, and were used in this context in William Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, and as an inducer of childbirth, as depicted in John Webster's The Duchess of Malfi.

Due to their high fiber to volume ratio, dried apricots are sometimes used to relieve constipation or induce diarrhea. Effects can be felt after eating as few as three.

Etymology

The scientific name armeniaca was first used by Gaspard Bauhin in his Pinax Theatri Botanici (page 442), referring to the species as Mala armeniaca "Armenian apple". It is sometimes stated that this came from Pliny the Elder, but it was not used by Pliny. Linnaeus took up Bauhin's epithet in the first edition of his Species Plantarum in 1753.[16]

The name apricot is probably derived from a tree mentioned as praecocia by Pliny. Pliny says "We give the name of apples (mala) ... to peaches (persica) and pomegranates (granata) ..."[17] Later in the same section he states "The Asiatic peach ripens at the end of autumn, though an early variety (praecocia) ripens in summer – these were discovered within the last thirty years ...".

The classical authors connected Greek armeniaca with Latin praecocia:[18] Pedanius Dioscorides' " ... Ἀρμενιακὰ, Ῥωμαιστὶ δὲ βρεκόκκια"[19] and Martial's "Armeniaca, et praecocia latine dicuntur".[20] Putting together the Armeniaca and the Mala obtains the well-known epithet, but there is no evidence the ancients did it; Armeniaca alone meant the apricot. Nonetheless, the 12th century Andalusian agronomist Ibn al-'Awwam refers to the species in the title of chapter 40 of his Kitab al-Filaha (The Book of Agriculture) as والتفاح الارمني, "apple from Armenia", stating that it is the same as المشمش or البرقوق ("al-mishmish" or "al-barqūq").

Accordingly, the American Heritage Dictionary under apricot derives praecocia from praecoquus, "cooked or ripened beforehand" [in this case meaning early ripening], becoming Greek πραικόκιον praikókion "apricot" and Arabic البرقوق al-barqūq, a term that has been used for a variety of different members of the genus Prunus (it currently refers primarily to the plum in most varieties of Arabic, but some writers use it as a catchall term for Prunus fruit).

The English name comes from earlier "abrecock" in turn from the Middle French abricot, from Catalan abercoc.[21] Both the Catalan and the Spanish albaricoque were adaptations of the Arabic, dating from the Moorish rule of Spain.

However, in Argentina, Chile, and Peru, the word for "apricot" is damasco, which could indicate that, to the Spanish settlers of Argentina, the fruit was associated with Damascus in Syria.[22] The word damasco is also the word for "apricot" in Portuguese (both European and Brazilian, though in Portugal the word alperce is also used).

In culture

The Chinese associate the apricot with education and medicine. For instance, the classical word 杏壇 (literally: "apricot altar") which means "educational circle", is still widely used in written language. Chuang Tzu, a Chinese philosopher in 4th century BCE, told a story that Confucius taught his students in a forum surrounded by the wood of apricot trees.[23] The association with medicine in turn comes from the common use of apricot kernels as a component in traditional Chinese medicine, and from the story of Dong Feng (董奉), a physician during the Three Kingdoms period, who required no payment from his patients except that they plant apricot trees in his orchard on recovering from their illnesses, resulting in a large grove of apricot trees and a steady supply of medicinal ingredients. The term "Expert of the Apricot Grove" (杏林高手) is still used as a poetic reference to physicians.

The fact that apricot season is very short has given rise to the very common Egyptian Arabic and Palestinian Arabic expression "filmishmish" ("in apricot [season]") or "bukra filmishmish" ("tomorrow in apricot [season]"), generally uttered as a riposte to an unlikely prediction, or as a rash promise to fulfill a request.

The Turkish idiom "bundan iyisi Şam'da kayısı" (literally, the only thing better than this is an apricot in Damascus) means "it doesn't get any better than this". It is used when something is the very best it can be, like a delicious apricot from Damascus.

Production trends

According to FAOSTAT, the top producers of apricots (in tonnes) in 2012 were as follows:[24]

| Rank | Country | Production (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | | 795,768 |

| 2 | | 460,000 |

| 3 | | 365,000 |

| 4 | | 269,000 |

| 5 | | 247,146 |

| 6 | | 192,500 |

| 7 | | 189,711 |

| 8 | | 122,405 |

| 9 | | 119,400 |

| 10 | | 98,772 |

See also

- Barack (brandy)

- List of apricot diseases

- Apricot plum, Prunus simonii

References

- ↑ Bortiri, E.; Oh, S.-H.; Jiang, J.; Baggett, S.; Granger, A.; Weeks, C.; Buckingham, M.; Potter, D.; Parfitt, D.E. (2001). "Phylogeny and systematics of Prunus (Rosaceae) as determined by sequence analysis of ITS and the chloroplast trnL-trnF spacer DNA". Systematic Botany 26 (4): 797–807. JSTOR 3093861.

- ↑ Flora of China: Armeniaca vulgaris

- ↑ Rushforth, K. (1999). Trees of Britain and Europe. Collins ISBN 0-00-220013-9.

- ↑ CultureGrams 2002 – Page 11 by CultureGrams

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "VII Symposium on Apricot Culture and Decline". Actahort.org. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- ↑ De Poerderlé, M. le Baron (1788). Manuel de l'Arboriste et du Forestier Belgiques: Seconde Édition: Tome Premier. Brussels: Emmanuel Flon. p. 682. Downloadable Google Books.

- ↑ B. Arakelyan, "Excavations at Garni, 1949–50" in Contributions to the Archaeology of Armenia, (Henry Field, ed.), Cambridge, 1968, page 29.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Huxley, A., ed. (1992). New RHS Dictionary of Gardening 1: 203–205. Macmillan ISBN 0-333-47494-5.

- ↑ Loudon, J.C. (1838). Arboretum Et Fruticetum Britannicum. Vol. II. London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green and Longmans. pp. 681–684. The genus is given as Armeniaca. Downloadable at Google Books.

- ↑ Agricultural Marketing Resource Center: Apricots

- ↑ Prunus sibirica – L.

- ↑ Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa - Watt & Breyer-Brandwijk (1962)

- ↑ The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink (ed. Andrew F. Smith). Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 9780195307962. Page 22.

- ↑ Lewis, WH and Elvin-Lewis, MPF (2003). Medical botany: plants affecting human health. Hoboken, New Jersey; John Wiley & Sons. Page 214.

- ↑ Milazzo, Stefania; Ernst, Edzard; Lejeune, Stephane; Boehm, Katja; Horneber, Markus (2011). Milazzo, Stefania, ed. "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews". Reviews: CD005476. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005476.pub3. PMID 22071824.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Linnaeus, C. (1753). Species Plantarum 1:474.

- ↑ N.H. Book XV Chapter XI, Rackham translation from the Loeb edition.

- ↑ Holland, Philemon (1601). "The XV. Booke of the Historie of Nature, Written by Plinius Secundus: Chap. XIII". Bill Thayer at penelope.uchicago.edu. pp. Note 31 by Thayer relates some scholarship of Jean Hardouin making the connection. Holland's chapter enumeration varies from Pliny's.

- ↑ De Materia Medica Book I Chapter 165.

- ↑ Epigram XIII Line 46.

- ↑ Webster's Third New International Dictionary under Apricot.

- ↑ "DICTIONARY > english–latin american spanish" (PDF).

- ↑ "《莊子·漁父》". Ctext.org. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- ↑ "Production of Apricot by countries". United Nation Food and Agriculture Organization. 2011. Retrieved 2013-08-23.

External links

-

Media related to Prunus armeniaca at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Prunus armeniaca at Wikimedia Commons -

The dictionary definition of apricot at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of apricot at Wiktionary