Appalachian Mountains

| Appalachian Mountains | |

|---|---|

| Appalachians | |

|

View from the slopes of Back Allegheny Mountain, looking east. Visible are Allegheny Mountain (in the Monongahela National Forest of West Virginia, middle distance) and Shenandoah Mountain (in the George Washington National Forest of Virginia, far distance). | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mount Mitchell |

| Elevation | 6,684 ft (2,037 m) |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 1,500 mi (2,400 km) |

| Geography | |

|

<div style="padding:2px 2px 2px 2px;>  | |

| Countries | United States and Canada |

| State/Province | Newfoundland and Labrador,[1][2] Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee, New Jersey, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama |

| Range coordinates | 40°N 78°W / 40°N 78°WCoordinates: 40°N 78°W / 40°N 78°W |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Taconic, Acadian, Alleghanian |

| Period | Ordovician-Permian |

The Appalachian Mountains (![]() i/ˌæpəˈleɪʃɨn/ or /ˌæpəˈlætʃɨn/,[note 1] French: les Appalaches), often called the Appalachians, are a system of mountains in eastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period and once reached elevations similar to those of the Alps and the Rocky Mountains before they were eroded.[3][4] The Appalachian chain is a barrier to east-west travel as it forms a series of alternating ridgelines and valleys oriented in opposition to any road running east-west.

i/ˌæpəˈleɪʃɨn/ or /ˌæpəˈlætʃɨn/,[note 1] French: les Appalaches), often called the Appalachians, are a system of mountains in eastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period and once reached elevations similar to those of the Alps and the Rocky Mountains before they were eroded.[3][4] The Appalachian chain is a barrier to east-west travel as it forms a series of alternating ridgelines and valleys oriented in opposition to any road running east-west.

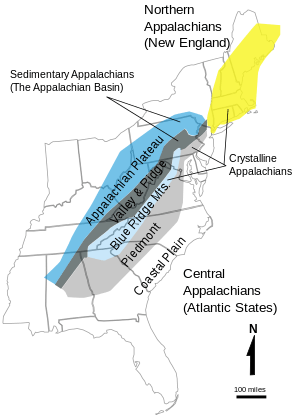

Definitions vary on the precise boundaries of the Appalachians. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) defines the Appalachian Highlands physiographic division as consisting of thirteen provinces: the Atlantic Coast Uplands, Eastern Newfoundland Atlantic, Maritime Acadian Highlands, Maritime Plain, Notre Dame and Mégantic Mountains, Western Newfoundland Mountains, Piedmont, Blue Ridge, Valley and Ridge, Saint Lawrence Valley, Appalachian Plateaus, New England province, and the Adirondack provinces.[5][6] A common variant definition does not include the Adirondack Mountains, which geologically belong to the Grenville Orogeny and have a different geological history from the rest of the Appalachians.[7][8][9]

Overview

The range is mostly located in the United States but extends into southeastern Canada, forming a zone from 100 to 300 mi (160 to 480 km) wide, running from the island of Newfoundland 1,500 mi (2,400 km) southwestward to Central Alabama in the United States. The range covers parts of the islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, which comprise an overseas territory of France. The system is divided into a series of ranges, with the individual mountains averaging around 3,000 ft (910 m). The highest of the group is Mount Mitchell in North Carolina at 6,684 feet (2,037 m), which is the highest point in the United States east of the Mississippi River.

The term Appalachian refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range. Most broadly, it refers to the entire mountain range with its surrounding hills and the dissected plateau region. The term is often used more restrictively to refer to regions in the central and southern Appalachian Mountains, usually including areas in the states of Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, Maryland, West Virginia, and North Carolina, as well as sometimes extending as far south as northern Georgia and western South Carolina, as far north as Pennsylvania and southern Ohio.

The Ouachita Mountains in Arkansas and Oklahoma were originally part of the Appalachians as well, but became disconnected through geologic history.

Origin of name

While exploring inland along the northern coast of Florida in 1528, the members of the Narváez expedition, including Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, found a Native American village near present-day Tallahassee, Florida whose name they transcribed as Apalchen or Apalachen [a.paˈla.tʃɛn]. The name was soon altered by the Spanish to Apalachee and used as a name for the tribe and region spreading well inland to the north. Pánfilo de Narváez's expedition first entered Apalachee territory on June 15, 1528, and applied the name. Now spelled "Appalachian," it is the fourth-oldest surviving European place-name in the US.[10]

After the de Soto expedition in 1540, Spanish cartographers began to apply the name of the tribe to the mountains themselves. The first cartographic appearance of Apalchen is on Diego Gutierrez's map of 1562; the first use for the mountain range is the map of Jacques le Moyne de Morgues in 1565.[11]

The name was not commonly used for the whole mountain range until the late 19th century. A competing and often more popular name was the "Allegheny Mountains," "Alleghenies," and even "Alleghania." In the early 19th century, Washington Irving proposed renaming the United States either Appalachia or Alleghania.[12]

In U.S. dialects in the southern regions of the Appalachians, the word is pronounced /ˌæpəˈlætʃɨnz/, with the third syllable sounding like "latch." In northern parts of the mountain range, it is pronounced /ˌæpəˈleɪtʃɨnz/ or /ˌæpəˈleɪʃɨnz/; the third syllable is like "lay", and the fourth "chins" or "shins."[13] Elsewhere, a commonly accepted pronunciation for the adjective Appalachian is /ˌæpəˈlætʃiən/, with the last two syllables "-ian" pronounced as in the word "Romanian."[14]

Geography

Regions

The whole system may be divided into three great sections:

- Northern - The northern section runs from the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador to the Hudson River. It includes the Long Range Mountains and Annieopsquotch Mountains on the island of Newfoundland, Chic-Choc Mountains and Notre Dame Range in Quebec and New Brunswick, scattered elevations and small ranges elsewhere in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, the Longfellow Mountains in Maine, the White Mountains in New Hampshire, the Green Mountains in Vermont, and The Berkshires in Massachusetts and Connecticut. The Metacomet Ridge Mountains in Connecticut and south-central Massachusetts, although contained within the Appalachian province, is a younger system and not geologically associated with the Appalachians. The Monteregian Hills, which cross the Green Mountains in Quebec, are also unassociated with the Appalachians.

- Central The central section goes from the Hudson Valley to the New River (Great Kanawha) running through Virginia and West Virginia. It comprises (excluding various minor groups) the Valley Ridges between the Allegheny Front of the Allegheny Plateau and the Great Appalachian Valley, the New York - New Jersey Highlands, the Taconic Mountains in New York, and a large portion of the Blue Ridge.

- Southern The southern section runs from the New River onwards. It consists of the prolongation of the Blue Ridge, which is divided into the Western Blue Ridge (or Unaka) Front and the Eastern Blue Ridge Front, the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, and the Cumberland Plateau.

The Adirondack Mountains in New York are sometimes considered part of the Appalachian chain but, geologically speaking, are a southern extension of the Laurentian Mountains of Canada.[7][8][9]

In addition to the true folded mountains, known as the ridge and valley province, the area of dissected plateau to the north and west of the mountains is usually grouped with the Appalachians. This includes the Catskill Mountains of southeastern New York, the Poconos in Pennsylvania, and the Allegheny Plateau of southwestern New York, western Pennsylvania, eastern Ohio and northern West Virginia. This same plateau is known as the Cumberland Plateau in southern West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, western Virginia, eastern Tennessee, and northern Alabama.

The dissected plateau area, while not actually made up of geological mountains, is popularly called "mountains," especially in eastern Kentucky and West Virginia, and while the ridges are not high, the terrain is extremely rugged. In Ohio and New York, some of the plateau has been glaciated, which has rounded off the sharp ridges, and filled the valleys to some extent. The glaciated regions are usually referred to as hill country rather than mountains.

The Appalachian region is generally considered the geographical divide between the eastern seaboard of the United States and the Midwest region of the country. The Eastern Continental Divide follows the Appalachian Mountains from Pennsylvania to Georgia.

The Appalachian Trail is a 2,175-mile (3,500 km) hiking trail that runs all the way from Mount Katahdin in Maine to Springer Mountain in Georgia, passing over or past a large part of the Appalachian system. The International Appalachian Trail is an extension of this hiking trail into the Canadian portion of the Appalachian range in Quebec.

Chief summits

The Appalachian belt includes, with the ranges enumerated above, the plateaus sloping southward to the Atlantic Ocean in New England, and south-eastward to the border of the coastal plain through the central and southern Atlantic states; and on the north-west, the Allegheny and Cumberland plateaus declining toward the Great Lakes and the interior plains. A remarkable feature of the belt is the longitudinal chain of broad valleys, including The Great Appalachian Valley, which in the southerly sections divides the mountain system into two unequal portions, but in the northernmost lies west of all the ranges possessing typical Appalachian features, and separates them from the Adirondack group. The mountain system has no axis of dominating altitudes, but in every portion the summits rise to rather uniform heights, and, especially in the central section, the various ridges and intermontane valleys have the same trend as the system itself. None of the summits reaches the region of perpetual snow.

Mountains of the Long Range in Newfoundland reach heights of nearly 3,000 ft (900 m). In the Chic-Choc and Notre Dame mountain ranges in Quebec, the higher summits rise to about 4,000 ft (1,200 m) elevation. Isolated peaks and small ranges in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick vary from 1,000 to 2,700 ft (300 to 800 m). In Maine several peaks exceed 4,000 ft (1,200 m)., including Mount Katahdin 5,267 feet (1,605 m). In New Hampshire, many summits rise above 5,000 ft (1,500 m), including Mount Washington in the White Mountains 6,288 ft (1,917 m), Adams 5,771 ft (1,759 m), Jefferson 5,712 ft (1,741 m), Monroe 5,380 ft (1,640 m)), Madison 5,367 ft (1,636 m), Lafayette 5,249 feet (1,600 m), and Lincoln 5,089 ft (1,551 m). In the Green Mountains the highest point, Mt. Mansfield, is 4,393 ft (1,339 m) in elevation; others include Killington Peak at 4,226 ft (1,288 m)., Camel's Hump at 4,083 ft (1,244 m)., Mt. Abraham at 4,006 ft (1,221 m)., and a number of other heights exceeding 3,000 ft (900 m).

In Pennsylvania, there are over sixty summits that rise over 2,500 ft (800 m); the summits of Mount Davis and Blue Knob rise over 3,000 ft (900 m). In Maryland, Eagle Rock and Dans Mountain are conspicuous points reaching 3,162 ft (964 m) and 2,882 ft (878 m) respectively. On the same side of the Great Valley, south of the Potomac, are the Pinnacle 3,007 feet (917 m) and Pidgeon Roost 3,400 ft (1,000 m). In West Virginia, more than 150 peaks rise above 4,000 ft (1,200 m)., including Spruce Knob 4,863 ft (1,482 m), the highest point in the Allegheny Mountains. A number of other points in the state rise above 4,800 ft (1,500 m). Snowshoe Mountain at Thorny Flat 4,848 ft (1,478 m) and Bald Knob 4,842 ft (1,476 m) are among the more notable peaks in West Virginia.

The Blue Ridge Mountains, rising in southern Pennsylvania and there known as South Mountain, attain elevations of about 2,000 ft (600 m) in that state. South Mountain achieves its highest point just below the Mason-Dixon line in Maryland at Quirauk Mountain 2,145 ft (654 m) and then diminishes in height southward to the Potomac River. Once in Virginia the Blue Ridge again reaches 2,000 ft (600 m) and higher. In the Virginia Blue Ridge, the following are some of the highest peaks north of the Roanoke River: Stony Man 4,031 ft (1,229 m), Hawksbill Mountain 4,066 ft (1,239 m), Apple Orchard Mountain 4,225 ft (1,288 m) and Peaks of Otter 4,001 and 3,875 ft (1,220 and 1,181 m). South of the Roanoke River, along the Blue Ridge, are Virginia's highest peaks including Whitetop Mountain 5,520 ft (1,680 m) and Mount Rogers 5,729 ft (1,746 m), the highest point in the Commonwealth.

Chief summits in the southern section of the Blue Ridge are located along two main crests — the Western or Unaka Front along the Tennessee-North Carolina border and the Eastern Front in North Carolina — or one of several "cross ridges" between the two main crests. Major subranges of the Eastern Front include the Black Mountains, Great Craggy Mountains, and Great Balsam Mountains, and its chief summits include Grandfather Mountain 5,964 ft (1,818 m) near the Tennessee-North Carolina border, Mount Mitchell 6,684 ft (2,037 m) in the Blacks, and Black Balsam Knob 6,214 ft (1,894 m) and Cold Mountain 6,030 ft (1,840 m) in the Great Balsams. The Western Blue Ridge Front is subdivided into the Unaka Range, the Bald Mountains, the Great Smoky Mountains, and the Unicoi Mountains, and its major peaks include Roan Mountain 6,285 ft (1,916 m) in the Unakas, Big Bald 5,516 ft (1,681 m) and Max Patch 4,616 ft (1,407 m) in the Bald Mountains, Clingmans Dome 6,643 ft (2,025 m), Mount Le Conte 6,593 feet (2,010 m), and Mount Guyot 6,621 ft (2,018 m) in the Great Smokies, and Big Frog Mountain 4,224 ft (1,287 m) near the Tennessee-Georgia-North Carolina border. Prominent summits in the cross ridges include Waterrock Knob (6,292 ft (1,918 m)) in the Plott Balsams. Across northern Georgia, numerous peaks exceed 4,000 ft (1,200 m), including Brasstown Bald, the state's highest, at 4,784 ft (1,458 m) and 4,696 ft (1,431 m) Rabun Bald.

Drainage

There are many geological issues concerning the rivers and streams of the Appalachians. In spite of the existence of the Great Appalachian Valley, many of the main rivers are transverse to the mountain system axis. The drainage divide of the Appalachians follows a tortuous course which crosses the mountainous belt just north of the New River in Virginia. South of the New River, rivers head into the Blue Ridge, cross the higher Unakas, receive important tributaries from the Great Valley, and traversing the Cumberland Plateau in spreading gorges (water gaps), escape by way of the Cumberland River and the Tennessee River rivers to the Ohio River and the Mississippi River, and thence to the Gulf of Mexico. In the central section, north of the New River, the rivers, rising in or just beyond the Valley Ridges, flow through great gorges to the Great Valley, and then across the Blue Ridge to tidal estuaries penetrating the coastal plain via the Roanoke River, James River, Potomac River, and Susquehanna River.

In the northern section the height of land lies on the inland side of the mountainous belt, and thus the main lines of drainage runs from north to south, exemplified by the Hudson River. However, the valley through which the Hudson River flows was cut by the gigantic glaciers of the Ice Ages — the same glaciers that deposited their terminal moraines in southern New York and formed the east-west Long Island.

Geology

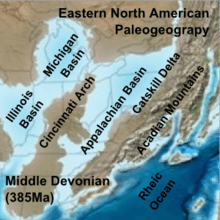

A look at rocks exposed in today's Appalachian mountains reveals elongated belts of folded and thrust faulted marine sedimentary rocks, volcanic rocks and slivers of ancient ocean floor, which provides strong evidence that these rocks were deformed during plate collision. The birth of the Appalachian ranges, some 480 Ma, marks the first of several mountain-building plate collisions that culminated in the construction of the supercontinent Pangaea with the Appalachians near the center. Because North America and Africa were connected, the Appalachians formed part of the same mountain chain as the Little Atlas in Morocco. This mountain range, known as the Central Pangean Mountains, extended into Scotland, from the North America/Europe collision (See Caledonian orogeny).

During the middle Ordovician Period (about 496-440 Ma), a change in plate motions set the stage for the first Paleozoic mountain-building event (Taconic orogeny) in North America. The once-quiet Appalachian passive margin changed to a very active plate boundary when a neighboring oceanic plate, the Iapetus, collided with and began sinking beneath the North American craton. With the birth of this new subduction zone, the early Appalachians were born. Along the continental margin, volcanoes grew, coincident with the initiation of subduction. Thrust faulting uplifted and warped older sedimentary rock laid down on the passive margin. As mountains rose, erosion began to wear them down. Streams carried rock debris down slope to be deposited in nearby lowlands. The Taconic Orogeny was just the first of a series of mountain building plate collisions that contributed to the formation of the Appalachians, culminating in the collision of North America and Africa (see Appalachian orogeny).[16]

By the end of the Mesozoic era, the Appalachian Mountains had been eroded to an almost flat plain.[16] It was not until the region was uplifted during the Cenozoic Era that the distinctive topography of the present formed.[17] Uplift rejuvenated the streams, which rapidly responded by cutting downward into the ancient bedrock. Some streams flowed along weak layers that define the folds and faults created many millions of years earlier. Other streams downcut so rapidly that they cut right across the resistant folded rocks of the mountain core, carving canyons across rock layers and geologic structures.

Mineral resources

The Appalachian Mountains contain major deposits of anthracite coal as well as bituminous coal. In the folded mountains the coal is in metamorphosed form as anthracite, represented by the Coal Region of northeastern Pennsylvania. The bituminous coal fields of western Pennsylvania, western Maryland, southeastern Ohio, eastern Kentucky, southwestern Virginia, and West Virginia contain the sedimentary form of coal.[18] The mountain top removal method of coal mining, in which entire mountain tops are removed, is currently threatening vast areas and ecosystems of the Appalachian Mountain region.[19]

The 1859 discovery of commercial quantities of petroleum in the Appalachian mountains of western Pennsylvania started the modern United States petroleum industry.[20] Recent discoveries of commercial natural gas deposits in the Marcellus Shale formation and Utica Shale formations have once again focused oil industry attention on the Appalachian Basin.

Some plateaus of the Appalachian Mountains contain metallic minerals such as iron and zinc.[21]

Ecology

Flora

The floras of the Appalachians are diverse and vary primarily in response to geology, latitude, elevation and moisture availability. Geobotanically, they constitute a floristic province of the North American Atlantic Region. The Appalachians consist primarily of deciduous broad-leaf trees and evergreen needle-leaf conifers, but also contain the evergreen broad-leaf American holly (Ilex opaca), and the deciduous needle-leaf conifer, the tamarack, or eastern larch (Larix laricina).

The dominant northern and high elevation conifer is the red spruce (Picea rubens), which grows from near sea level to above 4,000 ft (1,200 m) above sea level (asl) in northern New England and southeastern Canada. It also grows southward along the Appalachian crest to the highest elevations of the southern Appalachians, as in North Carolina and Tennessee. In the central Appalachians it is usually confined above 3,000 ft (900 m) asl, except for a few cold valleys in which it reaches lower elevations. In the southern Appalachians it is restricted to higher elevations. Another species is the black spruce (Picea mariana), which extends farthest north of any conifer in North America, is found at high elevations in the northern Appalachians, and in bogs as far south as Pennsylvania.

The Appalachians are also home to two species of fir, the boreal balsam fir (Abies balsamea), and the southern high elevation endemic, Fraser fir (Abies fraseri). Fraser fir is confined to the highest parts of the southern Appalachian Mountains, where along with red spruce it forms a fragile ecosystem known as the Southern Appalachian spruce-fir forest. Fraser fir rarely occurs below 5,500 ft (1,700 m), and becomes the dominant tree type at 6,200 ft (1,900 m).[22] By contrast, balsam fir is found from near sea level to the tree line in the northern Appalachians, but ranges only as far south as Virginia and West Virginia in the central Appalachians, where it is usually confined above 3,900 ft (1,200 m) asl, except in cold valleys. Curiously, it is associated with oaks in Virginia. The balsam fir of Virginia and West Virginia is thought by some to be a natural hybrid between the more northern variety and Fraser fir. While red spruce is common in both upland and bog habitats, balsam fir, as well as black spruce and tamarack, are more characteristic of the latter. However balsam fir also does well in soils with a pH as high as 6.[23]

Eastern or Canada hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) is another important evergreen needle-leaf conifer that grows along the Appalachian chain from north to south, but is confined to lower elevations than red spruce and the firs. It generally occupies richer and less acidic soils than the spruce and firs and is characteristic of deep, shaded and moist mountain valleys and coves. It is, unfortunately, subject to the hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae), an introduced insect, that is rapidly extirpating it as a forest tree. Less abundant, and restricted to the southern Appalachians, is Carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana). Like Canada hemlock, this tree suffers severely from the hemlock woolly adelgid.

Several species of pines characteristic of the Appalachians are eastern white pine (Pinus strobus ), Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana), pitch pine (Pinus rigida ), Table Mountain pine (Pinus pungens) and shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata). Red pine (Pinus resinosa) is a boreal species that forms a few high elevation outliers as far south as West Virginia. All of these species except white pine tend to occupy sandy, rocky, poor soil sites, which are mostly acidic in character. White pine, a large species valued for its timber, tends to do best in rich, moist soil, either acidic or alkaline in character. Pitch pine is also at home in acidic, boggy soil, and Table Mountain pine may occasionally be found in this habitat as well. Shortleaf pine is generally found in warmer habitats and at lower elevations than the other species. All the species listed do best in open or lightly shaded habitats, although white pine also thrives in shady coves, valleys, and on floodplains.

The Appalachians are characterized by a wealth of large, beautiful deciduous broadleaf (hardwood) trees. Their occurrences are best summarized and described in E. Lucy Braun's 1950 classic, Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America (Macmillan, New York). The most diverse and richest forests are the mixed mesophytic or medium moisture types, which are largely confined to rich, moist montane soils of the southern and central Appalachians, particularly in the Cumberland and Allegheny Mountains, but also thrive in the southern Appalachian coves. Characteristic canopy species are white basswood (Tilia heterophylla), yellow buckeye (Aesculus octandra), sugar maple (Acer saccharum), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera), white ash (Fraxinus americana ) and yellow birch (Betula alleganiensis). Other common trees are red maple (Acer rubrum), shagbark and bitternut hickories (Carya ovata and C. cordiformis) and black or sweet birch (Betula lenta ). Small understory trees and shrubs include flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), hophornbeam (Ostrya virginiana), witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) and spicebush (Lindera benzoin). There are also hundreds of perennial and annual herbs, among them such herbal and medicinal plants as American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius), goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis), bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) and black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa).

The foregoing trees, shrubs and herbs are also more widely distributed in less rich mesic forests that generally occupy coves, stream valleys and flood plains throughout the southern and central Appalachians at low and intermediate elevations. In the northern Appalachians and at higher elevations of the central and southern Appalachians these diverse mesic forests give way to less diverse "northern hardwoods" with canopies dominated only by American beech, sugar maple, American basswood (Tilia americana) and yellow birch and with far fewer species of shrubs and herbs.

Dryer and rockier uplands and ridges are occupied by oak-chestnut type forests dominated by a variety of oaks (Quercus spp.), hickories (Carya spp.) and, in the past, by the American chestnut (Castanea dentata). The American chestnut was virtually eliminated as a canopy species by the introduced fungal chestnut blight (Cryphonectaria parasitica), but lives on as sapling-sized sprouts that originate from roots, which are not killed by the fungus. In present day forest canopies chestnut has been largely replaced by oaks.

The oak forests of the southern and central Appalachians consist largely of black, northern red, white, chestnut and scarlet oaks (Quercus velutina, Q. rubra, Q. alba, Q. prinus and Q. coccinea) and hickories, such as the pignut (Carya glabra) in particular. The richest forests, which grade into mesic types, usually in coves and on gentle slopes, have dominantly white and northern red oaks, while the driest sites are dominated by chestnut oak, or sometimes by scarlet or northern red oaks. In the northern Appalachians the oaks, except for white and northern red, drop out, while the latter extends farthest north.

The oak forests generally lack the diverse small tree, shrub and herb layers of mesic forests. Shrubs are generally ericaceous, and include the evergreen mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia), various species of blueberries (Vaccinium spp.), black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), a number of deciduous rhododendrons (azaleas), and smaller heaths such as teaberry (Gaultheria procumbens) and trailing arbutus (Epigaea repens ). The evergreen great rhododendron (Rhododendron maximum) is characteristic of moist stream valleys. These occurrences are in line with the prevailing acidic character of most oak forest soils. In contrast, the much rarer chinquapin oak (Quercus muehlenbergii) demands alkaline soils and generally grows where limestone rock is near the surface. Hence no ericaceous shrubs are associated with it.

The Appalachian floras also include a diverse assemblage of bryophytes (mosses and liverworts), as well as fungi. Some species are rare and/or endemic. As with vascular plants, these tend to be closely related to the character of the soils and thermal environment in which they are found.

Eastern deciduous forests are subject to a number of serious insect and disease outbreaks. Among the most conspicuous is that of the introduced gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar), which infests primarily oaks, causing severe defoliation and tree mortality. But it also has the benefit of eliminating weak individuals, and thus improving the genetic stock, as well as creating rich habitat of a type through accumulation of dead wood. Because hardwoods sprout so readily, this moth is not as harmful as the hemlock woolly adelgid. Perhaps more serious is the introduced beech bark disease complex, which includes both a scale insect (Cryptococcus fagisuga) and fungal components.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries the Appalachian forests were subject to severe and destructive logging and land clearing, which resulted in the designation of the national forests and parks as well many state protected areas. However, these and a variety of other destructive activities continue, albeit in diminished forms; and thus far only a few ecologically based management practices have taken hold.

Fauna

Animals that characterize the Appalachian forests include five species of tree squirrels. The most commonly seen is the low to moderate elevation eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). Occupying similar habitat is the slightly larger fox squirrel (Sciurus niger) and the much smaller southern flying squirrel (Glaucomys volans). More characteristic of cooler northern and high elevation habitat is the red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus), whereas the Appalachian northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus fuscus), which closely resembles the southern flying squirrel, is confined to northern hardwood and spruce-fir forests.

As familiar as squirrels are the eastern cottontail rabbit (Silvilagus floridanus) and the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). The latter in particular has greatly increased in abundance as a result of the extirpation of the eastern wolf (Canis lupus lycaon) and the North American cougar. This has led to the overgrazing and browsing of many plants of the Appalachian forests, as well as destruction of agricultural crops. Other deer include the moose (Alces alces ), found only in the north, and the elk (Cervus canadensis), which, although once extirpated, is now making a comeback, through transplantation, in the southern and central Appalachians. In Quebec, the Chic-Chocs host the only population of caribou (Rangifer tarandus) south of the St. Lawrence River. An additional species that is common in the north but extends its range southward at high elevations to Virginia and West Virginia is the varying or snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus). However, these central Appalachian populations are scattered and very small.

Another species of great interest is the beaver (Castor canadensis), which is showing a great resurgence in numbers after its near extirpation for its pelt. This resurgence is bringing about a drastic alteration in habitat through the construction of dams and other structures throughout the mountains.

Other common forest animals are the black bear (Ursus americanus), striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis), raccoon (Procyon lotor), woodchuck (Marmota monax), bobcat (Felis rufus), gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and in recent years, the coyote (Canis latrans), another species favored by the advent of Europeans and the extirpation of eastern and red wolves. European boars were introduced in the early 20th century.

Characteristic birds of the forest are wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris), ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus), mourning dove (Zenaida macroura), common raven (Corvus corax), wood duck (Aix sponsa), great horned owl (Bubo virginianus), barred owl (Strix varia), screech owl (Megascops asio), red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), red-shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus), and northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis), as well as a great variety of "songbirds" (Passeriformes), like the warblers in particular.

Of great importance are the many species of salamanders and, in particular, the lungless species (Family Plethodontidae) that live in great abundance concealed by leaves and debris, on the forest floor. Most frequently seen, however, is the eastern or red-spotted newt (Notophthalmus viridescens), whose terrestrial eft form is often encountered on the open, dry forest floor. It has been estimated that salamanders represent the largest class of animal biomass in the Appalachian forests. Frogs and toads are of lesser diversity and abundance, but the wood frog (Rana sylvatica) is, like the eft, commonly encountered on the dry forest floor, while a number of species of small frogs, such as spring peepers (Pseudacris crucifer), enliven the forest with their calls. Salamanders and other amphibians contribute greatly to nutrient cycling through their consumption of small life forms on the forest floor and in aquatic habitats.

Although reptiles are less abundant and diverse than amphibians, a number of snakes are conspicuous members of the fauna. One of the largest is the non-venomous black rat snake (Elaphe obsoleta obsoleta), while the common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis) is among the smallest but most abundant. The American copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix) and the timber rattler (Crotalus horridus) are venomous pit vipers. There are few lizards, but the broad-headed skink (Eumeces laticeps), at up to 13 in (33 cm) in length, and an excellent climber and swimmer, is one of the largest and most spectacular in appearance and action. The most common turtle is the eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina), which is found in both upland and lowland forests in the central and southern Appalachians. Prominent among aquatic species is the large common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina), which occurs throughout the Appalachians.

Appalachian streams are notable for their highly diverse freshwater fish life. Among the most abundant and diverse are those of the minnow family (family Cyprinidae), while species of the colorful darters (Percina spp.) are also abundant.[24]

A characteristic fish of shaded, cool Appalachian forest streams is the wild brook or speckled trout (Salvelinus fontinalis), which is much sought after as a game fish. However in past years such trout waters have been much degraded by increasing temperatures due to timber cutting, pollution from various sources and potentially, global warming.

Influence on history

For a century, the Appalachians were a barrier to the westward expansion of the British colonies. The continuity of the mountain system, the bewildering multiplicity of its succeeding ridges, the tortuous courses and roughness of its transverse passes, a heavy forest, and dense undergrowth all conspired to hold the settlers on the seaward-sloping plateaus and coastal plains. Only by way of the Hudson and Mohawk Valleys, Cumberland Gap, and round about the southern termination of the system were there easy routes to the interior of the country, and these were long closed by powerful Native American tribes such as the Iroquois, Creek, and Cherokee, among others. Expansion was also blocked by the alliances the British Empire had forged with Native American tribes, the proximity of the Spanish colonies in the south and French activity throughout the interior.

In eastern Pennsylvania the Great Appalachian Valley, or Great Valley, was accessible by reason of a broad gateway between the end of South Mountain and the Highlands, and many Germans and Moravians settled here between the Susquehanna and Delaware Rivers forming the Pennsylvania Dutch community, some of whom even now speak a unique American dialect of German known as the "Pennsylvania German language" or "Pennsylvania Dutch." These latecomers to the New World were forced to the frontier to find cheap land. With their followers of both German, English and Scots-Irish origin, they worked their way southward and soon occupied all of the Shenandoah Valley, ceded by the Iroquois, and the upper reaches of the Great Valley tributaries of the Tennessee River, ceded by the Cherokee.

By 1755, the obstacle to westward expansion had been thus reduced by half; outposts of the English colonists had penetrated the Allegheny and Cumberland plateaus, threatening French monopoly in the transmontane region, and a conflict became inevitable. Making common cause against the French to determine the control of the Ohio valley, the unsuspected strength of the colonists was revealed, and the successful ending of the French and Indian War extended England's territory to the Mississippi. To this strength the geographic isolation enforced by the Appalachian mountains had been a prime contributor. The confinement of the colonies between an ocean and a mountain wall led to the fullest occupation of the coastal border of the continent, which was possible under existing conditions of agriculture, conducting to a community of purpose, a political and commercial solidarity, which would not otherwise have been developed. As early as 1700 it was possible to ride from Portland, Maine, to southern Virginia, sleeping each night at some considerable village. In contrast to this complete industrial occupation, the French territory was held by a small and very scattered population, its extent and openness adding materially to the difficulties of a disputed tenure. Bearing the brunt of this contest as they did, the colonies were undergoing preparation for the subsequent struggle with the home government. Unsupported by shipping, the American armies fought toward the sea with the mountains at their back protecting them against British leagued with the Native Americans. The few settlements beyond the Great Valley were free for self-defense because debarred from general participation in the conflict by reason of their position.

Before the French and Indian War, the Appalachian Mountains lay on the indeterminate boundary between Britain's colonies along the Atlantic and French areas centered in the Mississippi basin. After the French and Indian War, the Proclamation of 1763 restricted settlement for Great Britain's thirteen original colonies in North America to east of the summit line of the mountains (except in the northern regions where the Great Lakes formed the boundary). Although the line was adjusted several times to take frontier settlements into account and was impossible to enforce as law, it was strongly resented by backcountry settlers throughout the Appalachians. The Proclamation Line can be seen as one of the grievances which led to the American Revolutionary War. Many frontier settlers held that the defeat of the French opened the land west of the mountains to English settlement, only to find settlement barred by the British King's proclamation. The backcountry settlers who fought in the Illinois campaign of George Rogers Clark were motivated to secure their settlement of Kentucky.

With the formation of the United States, an important first phase of westward expansion in the late 18th century and early 19th century consisted of the migration of European-descended settlers westward across the mountains into the Ohio Valley through the Cumberland Gap and other mountain passes. The Erie Canal, finished in 1825, formed the first route through the Appalachians that was capable of large amounts of commerce.

See also

- Flora of the Appalachian Mountains

- Appalachia

- Appalachian culture

- Appalachian League

- Appalachian Mountain Club

- Appalachian Trail

Footnotes

References

Notes

- ↑ "International Appalachian Trail- Newfoundland". Iatnl.ca. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- ↑ Cees R. van Staal, Mineral Deposits of Canada: Regional Metallogeny: Pre-Carboniferous tectonic evolution and metallogeny of the Canadian Appalachians, Geological Survey of Canada website

- ↑ "The Mountains That Froze the World". AAAS. Retrieved 2012-04-04.

- ↑ "Geology of the Great Smoky Mountains". usgs. Retrieved 2012-04-04.

- ↑ "Physiographic divisions of the conterminous U. S.". U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 5 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ↑ "The Atlas of Canada — Physiographic Regions". Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Geomorphology From Space — Appalachian Mountains". NASA. Archived from the original on 6 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Adirondack Mountains". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Weidensaul, Scott (1994). Mountains of the Heart: A Natural History of the Appalachians. Fulcrum Publishing. pp. ix. ISBN 1-55591-139-0.

- ↑ After Florida, Cape Canaveral, and Dry Tortugas: Stewart, George (1945). Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States. New York: Random House. pp. 11–13, 17, 18.

- ↑ Walls, David (1978), "On the Naming of Appalachia" In An Appalachian Symposium, pp. 56-76.

- ↑ Stewart, George R. (1967). Names on the Land. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ↑ David Walls, "Appalachia." The Encyclopedia of Appalachia (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), 1006-1007.

- ↑ Define "Appalachian." Random House Dictionary, online at Dictionary.com. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ Blakey, Ron. "Paleogeography and Geologic Evolution of North America". Global Plate Tectonics and Paleogeography. Northern Arizona University. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Geologic Provinces of the United States: Appalachian Highlands Province". USGS. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- ↑ Poag, C. Wylie; Sevon, William D. (September 1989). "A record of Appalachian denudation in postrift Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary deposits of the U.S. Middle Atlantic continental margin". Geomorphology 2 (1-3): 119–157. doi:10.1016/0169-555X(89)90009-3.

- ↑ Ruppert, Leslie F. "Executive Summary—Coal Resource Assessment of Selected Coal Beds and Zones in the Northern and Central Appalachian Basin Coal Regions" (PDF). USGS. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- ↑ Palmer, M. A.; Bernhardt, E. S.; Schlesinger, W. H.; Eshleman, K. N.; Foufoula-Georgiou, E.; Hendryx, M. S.; Lemly, A. D.; Likens, G. E.; Loucks, O. L.; Power, M. E.; White, P. S.; Wilcock, P. R. (8 January 2010). "Mountaintop Mining Consequences". Science 327 (5962): 148–149. doi:10.1126/science.1180543. ISSN 1095-9203.

- ↑ Ryder, R.T. "Appalachian Basin Province (067)" (PDF). USGS. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- ↑ Mineral Resources of the Appalachian Region. USGS. 1968. Professional Paper 580.

- ↑ Rose Houk, Great Smoky Mountains National Park: A Natural History Guide (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1993), pp. 50-62.

- ↑ Fowells, H.A., 1965, Silvics of Forest Trees of the United States, Agricultural Handbook No. 271, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington D.C.

- ↑ Page, Lawrence M. and Brooks M. Burr 1991, A Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes, North America, North of Mexico, Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston

Sources

- Topographic maps and Geologic Folios of the United States Geological Survey

- Bailey Willis, The Northern Appalachians, and C. W. Hayes, The Southern Appalachians, both in National Geographic Monographs, vol. i.

- chaps, iii., iv. and v. of Miss E. C. Semple's American History and its Geographic Conditions (Boston, 1903).

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Brooks, Maurice (1965), The Appalachians: The Naturalist's America; illustrated by Lois Darling and Lo Brooks. Boston; Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Caudill, Harry M. (1963), Night Comes to the Cumberlands. ISBN 0-316-13212-8.

- Constantz, George (2004), Hollows, Peepers, and Highlanders: an Appalachian Mountain Ecology (2nd edition). West Virginia University Press; Morgantown. 359 p.

- Olson, Ted (1998), "Blue Ridge Folklife. University Press of Mississippi, 211 pages, ISBN 1-57806-023-0.

- Weidensaul, Scott (2000), Mountains of the Heart: A Natural History of the Appalachians. Fulcrum Publishing, 288 pages, ISBN 1-55591-139-0.

Appalachian flora and fauna-related journals:

- Castanea, the journal of the Southern Appalachian Botanical Society.

- Banisteria, a journal devoted to the natural history of Virginia.

- The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society.

External links

- Appalachian/Blue Ridge Forests images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu (slow modem version)

- Appalachian Mixed Mesophytic Forests images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu (slow modem version)

- University of Kentucky Appalachian Center

- Forests of the Central Appalachians Project Detailed inventories of forest species at dozens of sites.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||