Apostasy

Apostasy (/əˈpɒstəsi/; Greek: ἀποστασία (apostasia), "a defection or revolt") is the formal disaffiliation from, or abandonment or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion contrary to one's previous beliefs.[1] One who commits apostasy (or who apostatizes) is known as an apostate. The term apostasy is used by sociologists to mean renunciation and criticism of, or opposition to, a person's former religion, in a technical sense and without pejorative connotation.

The term is occasionally also used metaphorically to refer to renunciation of a non-religious belief or cause, such as a political party, brain trust, or a sports team.

Apostasy is generally not a self-definition: very few former believers call themselves apostates because of the negative connotation of the term.

Many religious groups and some states punish apostates. Apostates may be shunned by the members of their former religious group[2] or subjected to formal or informal punishment. This may be the official policy of the religious group or may simply be the voluntary action of its members. Certain churches may in certain circumstances excommunicate the apostate, while some religious scriptures demand the death penalty for apostates. Examples of punishment by death for apostates can be found under the Sharia code of Islam.[3][4]

Sociological definitions

The American sociologist Lewis A. Coser (following the German philosopher and sociologist Max Scheler) defines an apostate to be not just a person who experienced a dramatic change in conviction but "a man who, even in his new state of belief, is spiritually living not primarily in the content of that faith, in the pursuit of goals appropriate to it, but only in the struggle against the old faith and for the sake of its negation."[5][6]

The American sociologist David G. Bromley defined the apostate role as follows and distinguished it from the defector and whistleblower roles.[6]

- Apostate role: defined as one that occurs in a highly polarized situation in which an organization member undertakes a total change of loyalties by allying with one or more elements of an oppositional coalition without the consent or control of the organization. The narrative is one which documents the quintessentially evil essence of the apostate's former organization chronicled through the apostate's personal experience of capture and ultimate escape/rescue.

- Defector role: an organizational participant negotiates exit primarily with organizational authorities, who grant permission for role relinquishment, control the exit process, and facilitate role transmission. The jointly constructed narrative assigns primary moral responsibility for role performance problems to the departing member and interprets organizational permission as commitment to extraordinary moral standards and preservation of public trust.

- Whistle-blower role: defined here as one in which an organization member forms an alliance with an external regulatory unit through offering personal testimony concerning specific, contested organizational practices that is then used to sanction the organization. The narrative constructed jointly by the whistle blower and regulatory agency is one which depicts the whistle-blower as motivated by personal conscience and the organization by defense of the public interest.

Stuart A. Wright, an American sociologist and author, asserts that apostasy is a unique phenomenon and a distinct type of religious defection, in which the apostate is a defector "who is aligned with an oppositional coalition in an effort to broaden the dispute, and embraces public claims-making activities to attack his or her former group."[7]

International law

The United Nations Commission on Human Rights, considers the recanting of a person's religion a human right legally protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights:

The Committee observes that the freedom to 'have or to adopt' a religion or belief necessarily entails the freedom to choose a religion or belief, including the right to replace one's current religion or belief with another or to adopt atheistic views ... Article 18.2[8] bars coercion that would impair the right to have or adopt a religion or belief, including the use of threat of physical force or penal sanctions to compel believers or non-believers to adhere to their religious beliefs and congregations, to recant their religion or belief or to convert.[9]

Where punished

In 23 countries as of 2014, it was a criminal offense to abandon one's religion to become atheist, or convert to another religion.[10] All 23 of these countries were majority Islamic nations, of which 11 were in the Middle East. No country in the Americas or Europe has any law forbidding apostasy and restricting the freedom to convert to any religion. Furthermore, across the globe, no country with Christian, Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish, agnostic or atheist majority had any criminal or civil laws forbidding or encouraging apostasy, or had laws restricting an individual's right to convert from one religion to another.[11][12][13][14]

The following nations treat apostasy under their criminal laws as of 2014:

- Afghanistan – illegal (death penalty, although the U.S. and other coalition members have put pressure that has prevented recent executions)[15][16]

- Algeria – While Algeria has no direct laws against apostasy, its laws indirectly cover it. Article 144(2) of Algerian code specifies a prison term to anyone who criticizes or insults the creed or prophets of Islam through writing, drawing, declaration, or any other means; further, Algerian law makes conversion from Islam and proselytizing by non-Muslims an offense punishable with fine and prison term.[10]

- Brunei – per recently enacted Sharia law, Section 112(1) of the Brunei Penal Code states that a Muslim who declares himself non-Muslim commits a crime that is punishable with death, or with up to 30 year imprisonment, depending on the type of evidence. However, if the accused has recanted his conversion, he may be acquitted of the crime of apostasy.[10]

- Comoros[17]

- Egypt – illegal (3 years' imprisonment)[18]

- Iran – illegal (death penalty)[18][19][20]

- Iraq[17]

- Jordan – possibly illegal (fine, jail, child custody loss, marriage annulment) although officials claim otherwise, convictions are recorded for apostasy[21][22][23]

- Kuwait[17]

- Malaysia – illegal in five of thirteen states (fine, imprisonment, and flogging)[24][25]

- Maldives[17]

- Mauritania – illegal (death penalty if still apostate after 3 days)[26]

- Morocco – not illegal, but official Islamic council decreed apostates should be put to death.[10] Illegal to proselytise for religions other than Islam (15 years' imprisonment)[27]

- Nigeria[17]

- Oman – illegal (prison) according to Article 209 of Oman penal code, and denies child custody rights under Article 32 of Personal Status Law[10]

- Qatar – illegal (death penalty)[28]

- Saudi Arabia – illegal (death penalty, although there have been no recently reported executions)[18][29]

- Somalia – illegal (death penalty)[30]

- Sudan – illegal (death penalty)[31]

- Syria[17]

- United Arab Emirates – illegal (3 years' imprisonment, flogging)[32]

- Yemen – illegal (death penalty)[28]

A few Islamic majority nations, not in the above list, prosecute apostasy even though they do not have apostasy laws, and only have blasphemy laws. In these nations, there is no general agreement or legal code to define "blasphemy". The lack of definition and legal vagueness has been used to include apostasy as a form of blasphemy. For example, in Indonesia, apostasy is indirectly covered under 156(a) of the Penal Code and 1965 Presidential edict, the phrase used in the Blasphemy Law is penyalahgunaan dan/atau penodaan agama, meaning "to misuse or disgrace a religion". Persons accused of blasphemy have included murtad (apostate), kafir (non-Muslim/unbeliever), aliran sesat (deviant group), sesat (deviant), or aliran kepercayaan (mystical believers). Indonesia has invoked blasphemy laws to address crimes of riddah (apostasy); zandaqah (heresy); nifaq (hypocrisy); and kufr (unbelief). Islamic activists have demanded, and state prosecutors have proposed, punishments ranging from prison sentences to death for such crimes.[33][34][35]

Religious views

Baha'i

Both marginal and apostate Baha'is have existed in the Baha'i community[36] who are known as nāqeżīn.[37]

Muslims often regard adherents of the Bahá'í faith as apostates from Islam,[38] and there have been cases in some Muslim countries where Baha'is have been harassed and persecuted.[39]

Christianity

The Christian understanding of apostasy is "a willful falling away from, or rebellion against, Christian truth. Apostasy is the rejection of Christ by one who has been a Christian ...", though many believe that biblically this is impossible ('once saved, forever saved').[40] "Apostasy is the antonym of conversion; it is deconversion."[41] The Greek noun apostasia (rebellion, abandonment, state of apostasy, defection)[42] is found only twice in the New Testament (Acts 21:21; 2 Thessalonians 2:3).[43] However, "the concept of apostasy is found throughout Scripture."[44] The Dictionary of Biblical Imagery states that "There are at least four distinct images in Scripture of the concept of apostasy. All connote an intentional defection from the faith."[45] These images are: Rebellion; Turning Away; Falling Away; Adultery.[46]

- Rebellion: "In classical literature apostasia was used to denote a coup or defection. By extension the Septuagint always uses it to portray a rebellion against God (Joshua 22:22; 2 Chronicles 29:19)."[46]

- Turning away: "Apostasy is also pictured as the heart turning away from God (Jeremiah 17:5-6) and righteousness (Ezekiel 3:20). In the OT it centers on Israel's breaking covenant relationship with God though disobedience to the law (Jeremiah 2:19), especially following other gods (Judges 2:19) and practicing their immorality (Daniel 9:9-11) ... Following the Lord or journeying with him is one of the chief images of faithfulness in the Scriptures ... The ... Hebrew root (swr) is used to picture those who have turned away and ceased to follow God ('I am grieved that I have made Saul king, because he has turned away from me,' 1 Samuel 15:11) ... The image of turning away from the Lord, who is the rightful leader, and following behind false gods is the dominant image for apostasy in the OT."[46]

- Falling away: "The image of falling, with the sense of going to eternal destruction, is particularly evident in the New Testament ... In his [Christ's] parable of the wise and foolish builder, in which the house built on sand falls with a crash in the midst of a storm (Matthew 7:24-27) ... he painted a highly memorable image of the dangers of falling spiritually."[47]

- Adultery: One of the most common images for apostasy in the Old Testament is adultery.[46] "Apostasy is symbolized as Israel the faithless spouse turning away from Yahweh her marriage partner to pursue the advances of other gods (Jeremiah 2:1-3; Ezekiel 16) ... 'Your children have forsaken me and sworn by god that are not gods. I supplied all their needs, yet they committed adultery and thronged to the houses of prostitutes' (Jeremiah 5:7, NIV). Adultery is used most often to graphically name the horror of the betrayal and covenant breaking involved in idolatry. Like literal adultery it does include the idea of someone blinded by infatuation, in this case for an idol: 'How I have been grieved by their adulterous hearts ... which have lusted after their idols' (Ezekiel 6:9)."[46]

Speaking with specific regard to apostasy in Christianity, Michael Fink writes:

Apostasy is certainly a biblical concept, but the implications of the teaching have been hotly debated.[48] The debate has centered on the issue of apostasy and salvation. Based on the concept of God's sovereign grace, some hold that, though true believers may stray, they will never totally fall away. Others affirm that any who fall away were never really saved. Though they may have "believed" for a while, they never experienced regeneration. Still others argue that the biblical warnings against apostasy are real and that believers maintain the freedom, at least potentially, to reject God's salvation.[49]

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses practice a form of shunning which they refer to as "disfellowshipping".[50] If a person baptized as a Jehovah's Witness later leaves the organization because they disagree with the religion's teachings, the person is shunned, and labeled by the organization as an "apostate".[51][51] Watch Tower Society literature describes apostates as "mentally diseased".[52][53]

Hinduism

There is no concept of heresy or apostasy in Hinduism. Hinduism grants absolute freedom for an individual to leave or choose his or her faith; on the Path of God. Hindus believe all sincere faiths ultimately lead to the same God.[54]

Islam

In Islamic literature, apostasy is called irtidād or ridda; an apostate is called murtadd, which literally means 'one who turns back' from Islam.[56] Someone born to a Muslim parent, or who has previously converted to Islam, becomes a murtadd if he or she verbally denies any principle of belief proscribed by Qur'an or a Hadith, deviates from approved Islamic belief (ilhad), or if he or she commits an action such as treating a copy of the Qurʾan with disrespect.[57][58][59] A person born to a Muslim parent who later rejects Islam is called a murtad fitri, and a person who converted to Islam and later rejects the religion is called a murtad milli.[60][61][62]

There are multiple verses in Qur'an that condemn apostasy,[63] and multiple Hadiths include statements that support the death penalty for apostasy.[64]

The concept and crime of Apostasy has been extensively covered in Islamic literature since 7th century.[65] A person is considered apostate if he or she converts from Islam to another religion.[66] A person is an apostate even if he or she believes in most of Islam, but verbally or in writing denies of one or more principles or precepts of Islam. For example, if a Muslim declares that the universe has always existed, he or she is an apostate; similarly, a Muslim who doubts the existence of Allah, enters a church or temple, makes offerings to and worships an idol or stupa or any image of God, celebrates festivals of non-Muslim religion, helps build a church or temple, confesses a belief in rebirth or incarnation of God, disrespects Qur'an or Islam's Prophet are all individually sufficient evidence of apostasy.[67][68][69]

The Islamic law on apostasy and the punishment is considered by many Muslims to be one of the immutable laws under Islam.[70] It is a hudud crime,[71][72] which means it is a crime against God,[73] and the punishment has been fixed by God. The punishment for apostasy includes[74] state enforced annulment of his or her marriage, seizure of the person's children and property with automatic assignment to guardians and heirs, and death for the apostate.[65][75][76]

According to some scholars, if a Muslim consciously and without coercion declares their rejection of Islam and does not change their mind after the time allocated by a judge for research, then the penalty for male apostates is death, and for females life imprisonment.[77][78]

According to the Ahmadi Muslim sect, there is no punishment for apostasy, neither in the Qur'an nor as taught by the founder of Islam, Muhammad.[79] This position of the Ahmadi sect is not widely accepted in other sects of Islam, and the Ahmadi sect acknowledges that major sects have a different interpretation and definition of apostasy in Islam.[80] Ulama of major sects of Islam consider the Ahmadi Muslim sect as kafirs (infidels)[81] and apostates.[82][83]

Today, apostasy is a crime in 23 out 49 Muslim majority countries; in many other Muslim nations such as Indonesia and Morocco, apostasy is indirectly covered by other laws.[10][84] It is subject in some countries, such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, to the death penalty, although executions for apostasy are rare. Apostasy is legal in secular Muslim countries such as Turkey.[85] In numerous Islamic majority countries, many individuals have been arrested and punished for the crime of apostasy without any associated capital crimes.[86][87][88][17] In a 2013 report based on an international survey of religious attitudes, more than 50% of the Muslim population in 6 Islamic countries supported the death penalty for any Muslim who leaves Islam (apostasy).[89][90] A similar survey of the Muslim population in the United Kingdom, in 2007, found nearly a third of 16 to 24-year-old faithfuls believed that Muslims who convert to another religion should be executed, while less than a fifth of those over 55 believed the same.[91]

Muslim historians recognize 632 AD as the year when the first regional apostasy from Islam emerged, immediately after the death of Muhammed.[92] The civil wars that followed are now called Riddah wars (Wars of Islamic Apostasy), with the massacre at Battle of Karbala holding a special place for Shia Muslims.

Judaism

The term apostasy is also derived from Greek ἀποστάτης, meaning "political rebel," as applied to rebellion against God, its law and the faith of Israel (in Hebrew מרד) in the Hebrew Bible. Other expressions for apostate as used by rabbinical scholars are "mumar" (מומר, literally "the one that is changed") and "poshea yisrael" (פושע ישראל, literally, "transgressor of Israel"), or simply "kofer" (כופר, literally "denier" and heretic).

The Torah states:

If thy brother, the son of thy mother, or thy son, or thy daughter, or the wife of thy bosom, or thy friend, which [is] as thine own soul, entice thee secretly, saying, Let us go and serve other gods, which thou hast not known, thou, nor thy fathers; [Namely], of the gods of the people which [are] round about you, nigh unto thee, or far off from thee, from the [one] end of the earth even unto the [other] end of the earth; Thou shalt not consent unto him, nor hearken unto him; neither shall thine eye pity him, neither shalt thou spare, neither shalt thou conceal him: But thou shalt surely kill him; thine hand shall be first upon him to put him to death, and afterwards the hand of all the people. And thou shalt stone him with stones, that he die; because he hath sought to thrust thee away from the LORD thy God, which brought thee out of the land of Egypt, from the house of bondage.—Deuteronomy 13:6–10[93]

The prophetic writings of Isaiah and Jeremiah provide many examples of defections of faith found among the Israelites (e.g., Isaiah 1:2–4 or Jeremiah 2:19), as do the writings of the prophet Ezekiel (e.g., Ezekiel 16 or 18). Israelite kings were often guilty of apostasy, examples including Ahab (I Kings 16:30–33), Ahaziah (I Kings 22:51–53), Jehoram (2 Chronicles 21:6,10), Ahaz (2 Chronicles 28:1–4), or Amon (2 Chronicles 33:21–23) among others. (Amon's father Manasseh was also apostate for many years of his long reign, although towards the end of his life he renounced his apostasy. Cf. 2 Chronicles 33:1–19)

In the Talmud, Elisha Ben Abuyah (known as Aḥer) is singled out as an apostate and epicurean by the Pharisees.

During the Spanish inquisition, a systematic conversion of Jews to Christianity took place, which occurred under duress and threats of torture and forced expulsion. These cases of apostasy provoked the indignation of the Jewish communities in Spain.

Several notorious Inquisitors, such as Tomás de Torquemada, and Don Francisco the archbishop of Coria, were descendants of apostate Jews. Other apostates who made their mark in history by attempting the conversion of other Jews in the 14th century include Juan de Valladolid and Astruc Remoch.

Abraham Isaac Kook,[94][95] first Chief Rabbi of the Jewish community in then Palestine, held that atheists were not actually denying God: rather, they were denying one of man's many images of God. Since any man-made image of God can be considered an idol, Kook held that, in practice, one could consider atheists as helping true religion burn away false images of god, thus in the end serving the purpose of true monotheism.

In practice, Judaism does not follow the Torah's prescription on this point: there is no punishment today for leaving Judaism, other than being excluded from participating in the rituals of the Jewish community, including leading worship, being called to the Torah and being buried in a Jewish cemetery.

Sikhism

Sikhism teaches that it is up to the individual to leave or choose his faith, on the Path of God. Each individual will ultimately find his/her path to truth/God and there is only one God for everyone and paths/religions could be different. Every human being is the Light of the Divine contained in a human form.[96]

Other religious movements

Controversies over new religious movements (NRMs) have often involved apostates, some of whom join organizations or web sites opposed to their former religions. A number of scholars have debated the reliability of apostates and their stories, often called "apostate narratives".

The role of former members, or "apostates", has been widely studied by social scientists. At times, these individuals become outspoken public critics of the groups they leave. Their motivations, the roles they play in the anti-cult movement, the validity of their testimony, and the kinds of narratives they construct, are controversial. Some scholars like David G. Bromley, Anson Shupe, and Brian R. Wilson have challenged the validity of the testimonies presented by critical former members. Wilson discusses the use of the atrocity story that is rehearsed by the apostate to explain how, by manipulation, coercion, or deceit, he was recruited to a group that he now condemns.[97]

Sociologist Stuart A. Wright explores the distinction between the apostate narrative and the role of the apostate, asserting that the former follows a predictable pattern, in which the apostate utilizes a "captivity narrative" that emphasizes manipulation, entrapment and being victims of "sinister cult practices". These narratives provide a rationale for a "hostage-rescue" motif, in which cults are likened to POW camps and deprogramming as heroic hostage rescue efforts. He also makes a distinction between "leavetakers" and "apostates", asserting that despite the popular literature and lurid media accounts of stories of "rescued or recovering 'ex-cultists'", empirical studies of defectors from NRMs "generally indicate favorable, sympathetic or at the very least mixed responses toward their former group".[98]

One camp that broadly speaking questions apostate narratives includes David G. Bromley,[99][100] Daniel Carson Johnson,[101] Dr. Lonnie D. Kliever (1932–2004),[102] Gordon Melton,[103] and Bryan R. Wilson.[104] An opposing camp less critical of apostate narratives as a group includes Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi,[105] Dr. Phillip Charles Lucas,[106][107][108] Jean Duhaime,[109] Mark Dunlop,[110][111] Michael Langone,[112] and Benjamin Zablocki.[113]

Some scholars have attempted to classify apostates of NRMs. James T. Richardson proposes a theory related to a logical relationship between apostates and whistleblowers, using Bromley's definitions,[114] in which the former predates the latter. A person becomes an apostate and then seeks the role of whistleblower, which is then rewarded for playing that role by groups that are in conflict with the original group of membership such as anti-cult organizations. These organizations further cultivate the apostate, seeking to turn him or her into a whistleblower. He also describes how in this context, apostates' accusations of "brainwashing" are designed to attract perceptions of threats against the well being of young adults on the part of their families to further establish their newfound role as whistleblowers.[115] Armand L. Mauss, define true apostates as those exiters that have access to oppositional organizations which sponsor their careers as such, and which validate the retrospective accounts of their past and their outrageous experiences in new religions, making a distinction between these and whistleblowers or defectors in this context.[116] Donald Richter, a current member of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (FLDS) writes that this can explain the writings of Carolyn Jessop and Flora Jessop, former members of the FLDS church who consistently sided with authorities when children of the YFZ ranch were removed over charges of child abuse.

Massimo Introvigne in his Defectors, Ordinary Leavetakers and Apostates[117] defines three types of narratives constructed by apostates of new religious movements:

- Type I narratives characterize the exit process as defection, in which the organization and the former member negotiate an exiting process aimed at minimizing the damage for both parties.

- Type II narratives involve a minimal degree of negotiation between the exiting member, the organization they intend to leave, and the environment or society at large, implying that the ordinary apostate holds no strong feelings concerning his past experience in the group. They may make "comments on the organization's more negative features or shortcomings" while also recognizing that there was "something positive in the experience."

- Type III narratives are characterized by the ex-member dramatically reversing their loyalties and becoming a professional enemy of the organization they have left. These apostates often join an oppositional coalition fighting the organization, often claiming victimization.

Introvigne argues that apostates professing Type II narratives prevail among exiting members of controversial groups or organizations, while apostates that profess Type III narratives are a vociferous minority.

Ronald Burks, a psychology assistant at the Wellspring Retreat and Resource Center, in a study comparing Group Psychological Abuse Scale (GPA) and Neurological Impairment Scale (NIS) scores in 132 former members of cults and cultic relationships, found a positive correlation between intensity of reform environment as measured by the GPA and cognitive impairment as measured by the NIS. Additional findings were a reduced earning potential in view of the education level that corroborates earlier studies of cult critics (Martin 1993; Singer & Ofshe, 1990; West & Martin, 1994) and significant levels of depression and dissociation agreeing with Conway & Siegelman, (1982), Lewis & Bromley, (1987) and Martin, et al. (1992).[118]

Sociologists Bromley and Hadden note a lack of empirical support for claimed consequences of having been a member of a "cult" or "sect", and substantial empirical evidence against it. These include the fact that the overwhelming proportion of people who get involved in NRMs leave, most short of two years; the overwhelming proportion of people who leave do so of their own volition; and that two-thirds (67%) felt "wiser for the experience".[119]

According to F. Derks and psychologist of religion Jan van der Lans, there is no uniform post-cult trauma. While psychological and social problems upon resignation are not uncommon, their character and intensity are greatly dependent on the personal history and on the traits of the ex-member, and on the reasons for and way of resignation.[120]

The report of the "Swedish Government's Commission on New Religious Movements" (1998) states that the great majority of members of new religious movements derive positive experiences from their subscription to ideas or doctrines which correspond to their personal needs, and that withdrawal from these movements is usually quite undramatic, as these people leave feeling enriched by a predominantly positive experience. Although the report describes that there are a small number of withdrawals that require support (100 out of 50,000+ people), the report did not recommend that any special resources be established for their rehabilitation, as these cases are very rare.[121]

Examples

Historical persons

- Julian the Apostate, the Roman emperor, given a Christian education by those who assassinated his family, rejected his upbringing and declared his belief in Neoplatonism once it was safe to do so.

- Sir Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford was declared 'The Great Apostate' by Parliament in 1628 for changing his political support from Parliament to Charles I, thus shifting his religious support from Calvinism to Arminianism.

- Abraham ben Abraham, (Count Valentine (Valentin, Walentyn) Potocki), a Polish nobleman of the Potocki family who is claimed to have converted to Judaism and was burned at the stake in 1749 because he had renounced Catholicism and had become an observant Jew.

- Maria Monk, sometimes considered an apostate of the Catholic Church, though there is little evidence that she ever was a Catholic.

- Lord George Gordon, initially a zealous Protestant and instigator of the Gordon riots of 1780, finally renounced Christianity and converted to Judaism, for which he was ostracized.

- Martin Luther, the founder of Lutheranism, was considered both an apostate and heretic by the strict definition of apostasy according to the Catholic Church. Most Protestants would naturally disagree, calling him a liberator and revolutionary.

Recent times

- In 2011, Youcef Nadarkhani, an Iranian pastor who converted from Islam to Christianity at the age of 19, was convicted for apostasy and was sentenced to death.[122]

- In 2013, Raif Badawi, a Saudi Arabian blogger, was found guilty of apostasy by the high court, which has a penalty of death.[123]

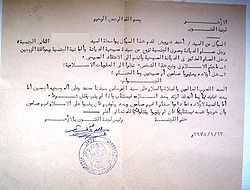

- In 2014, Meriam Yehya Ibrahim Ishag (aka Adraf Al-Hadi Mohammed Abdullah), a pregnant Sudanese woman, was convicted of apostasy for converting to Christianity from Islam. The government ruled that her father was Muslim, a female child takes the father's religion under Sudan's Islamic law.[124] By converting to Christianity, she had committed apostasy, a crime punishable by death. Mrs Ibrahim Ishag was sentenced to death. She was also convicted of adultery on the grounds that her marriage to a Christian man from South Sudan was void under Sudan's version of Islamic law, which says Muslim women cannot marry non-Muslims.[31]

- Ayaan Hirsi Ali, labelled an apostate by Theo van Gogh according to Ayaan Hirsi Ali[125]

- Tasleema Nasreen from Bangladesh, the author of Lajja, has been declared apostate – "an apostate appointed by imperialist forces to vilify Islam" – by several fundamentalist clerics in Dhaka[126]

- Younus Shaikh from Pakistan was sentenced to death for his remarks on Muhammad, considered blasphemous; but later on the judge ordered a re-trial.[127]

- Brian Moore spoke strongly about the effect of the Catholic Church on life in Ireland.

See also

References

- ↑ Mallet, Edme-François, and François-Vincent Toussaint. "Apostasy." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Rachel LaFortune. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2012. Web. 1 April 2015. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0002.748>. Trans. of "Apostasie," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 1. Paris, 1751.

- ↑ Muslim apostates cast out and at risk from faith and family, The Times, February 05, 2005

- ↑ [Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na’im (1996): p. 352]

- ↑ [Shafi'i: Rawda al-talibin, 10.7, Hanafi: Ibn 'Abidin: Radd al-muhtar 3.287, Maliki: al-Dardir: al-Sharh al-saghir, 4.435, and Hanbali: al-Bahuti: Kashshaf al-qina', 6.170 (see The Struggle to Constitute and Sustain Productive Orders: Vincent Ostrom's Quest to Understand Human Affairs), Mark Sproule-Jones et al (2008), Lexington Books, ISBN 978-0739126288)]

- ↑ Lewis A. Coser The Age of the Informer Dissent:1249–54, 1954

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Bromley, David G. (Ed.) The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Apostates in the Transformation of Religious Movements CT, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7

- ↑ Wright, Stuart, A., Exploring Factors that Shape the Apostate Role, in Bromley, David G., The Politics of Religious Apostasy, pp. 109, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7

- ↑

Article 18.2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Article 18.2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. - ↑ CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.4, General Comment No. 22., 1993

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Laws Criminalizing Apostasy Library of Congress (2014)

- ↑ Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life (September 2012), Rising Tide of Restrictions on Religion''

- ↑ El-Awa, Mohamed S. Punishment in Islamic Law, American Trust Pub., 1981

- ↑ Peters, Rudolph, and Gert JJ De Vries. Apostasy in Islam, Die Welt des Islams (1976): 1-25.

- ↑ Rehman, Javaid, Freedom of expression, apostasy, and blasphemy within Islam: Sharia, criminal justice systems, and modern Islamic state practices: Javaid Rehman investigates the uses and abuses of certain interpretations of Sharia law and the Quran, Criminal Justice Matters, 79.1 (2010): pages 4–5

- ↑ BBC News, "Afghanistan treads religious tightrope", quote: "Others point out that no one has been executed for apostasy in Afghanistan even under the Taleban ... two Afghan editors accused of blasphemy both faced the death sentence, but one claimed asylum abroad and the other was freed after a short spell in jail."

- ↑ CNS news, "Plight of Christian Converts Highlights Absence of Religious Freedom in Afghanistan", quote: "A Christian convert from Islam named Abdul Rahman was sentenced to death in 2006 for apostasy, and only after the U.S. and other coalition members applied pressure on the Karzai government was he freed and allowed to leave the country."

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 "Laws Penalizing Blasphemy, Apostasy and Defamation of Religion are Widespread". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 21 November 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Ali Eteraz. "Supporting Islam's apostates". the Guardian. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ The Telegraph, "Hanged for Being a Christian in Iran

- ↑ "Iran hangs man convicted of apostasy". Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/jordan/090922/jordanian-poet-trial-apostacy,

- ↑ "Convert to Christianity flees Jordan under threat to lose custody of his children". assistnews.net. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ↑ "CTV News | Top Stories - Breaking News - Top News Headlines". ctv.ca. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ↑ "Malaysia's shackles on religious freedom". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2007-06-22.

- ↑ "http://www.malaysianbar.org.my/index2.php?option=com_content&do_pdf=1&id=11916". malaysianbar.org.my. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ↑ "MAURITANIA" (PDF). 14 June 2012. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ↑ Saeed, A.; Saeed, H. (2004). Freedom of Religion, Apostasy and Islam. Ashgate. p. 19. ISBN 9780754630838. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "/news/archives/article.php". Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ CTV news, "'Apostasy' laws widespread in Muslim world", quote: "Islamic Shariah law considers conversion to any religion apostasy and most Muslim scholars agree the punishment is death. Saudi Arabia considers Shariah the law of the land, though there have been no reported cases of executions of converts from Islam in recent memory."

- ↑ "BBC NEWS - Africa - Somali executed for 'apostasy'". Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Sudan woman faces death for apostasy". BBC News. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ↑ "Crimes punishable by death in the UAE include…apostasy | Freedom Center Students". freedomcenterstudents.org. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ↑ Crouch, Melissa. "Shifting conceptions of state regulation of religion: the Indonesian Draft Law on Inter-religious Harmony." (2013)

- ↑ Peri Bearman, Wolfhart Heinrichs & Bernard Weiss, eds., The Law Applied: Contextualizing the Islamic Shari'a (IB Taurus, 2008)

- ↑ Saeed, Abdullah, AMBIGUITIES OF APOSTASY AND THE REPRESSION OF MUSLIM DISSENT, The Review of Faith & International Affairs 9.2 (2011); pages 31–38

- ↑ Momen, Moojan (1 September 2007). "Marginality and apostasy in the Baha'i community". Religion 37 (3): 187–209. doi:10.1016/j.religion.2007.06.008.

- ↑ Afshar, Iraj (August 18, 2011). "ĀYATĪ, ʿABD-AL-ḤOSAYN". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ↑ "The Baabis and Baha’is are not Muslims - islamqa.info". islam-qa.com. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ↑ "Apostates from Islam | The Weekly Standard". weeklystandard.com. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ↑ Richard A. Muller, Dictionary of Greek and Latin Theological Terms: Drawn Principally from Protestant Scholastic Theology, 41. The Tyndale Bible Dictionary defines apostasy as a "Turning against God, as evidenced by abandonment and repudiation of former beliefs. The term generally refers to a deliberate renouncing of the faith by a once sincere believer ..." ("Apostasy," Walter A. Elwell and Philip W. Comfort, editors, 95).

- ↑ Paul W. Barnett, Dictionary of the Later New Testament and its Developments, "Apostasy," 73. Scott McKnight says, "Apostasy is a theological category describing those who have voluntarily and consciously abandoned their faith in the God of the covenant, who manifests himself most completely in Jesus Christ" (Dictionary of Theological Interpretation of the Bible, "Apostasy," 58).

- ↑ Walter Bauder, "Fall, Fall Away," The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology (NIDNTT), 3:606.

- ↑ Michael Fink, "Apostasy," in the Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary, 87. In Acts 21:21, "Paul was falsely accused of teaching the Jews apostasy from Moses ... [and] he predicted the great apostasy from Christianity, foretold by Jesus (Matt. 24:10-12), which would precede 'the Day of the Lord' (2 Thess. 2:2f.)" (D. M. Pratt, International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, "Apostasy," 1:192). Some pre-tribulation adherents in Protestantism believe that the apostasy mentioned in 2 Thess. 2:3 can be interpreted as the pre-tribulation Rapture of all Christians. This is because apostasy means departure (translated so in the first seven English translations) (Dr. Thomas Ice, Pre-Trib Perspective, March 2004, Vol.8, No.11).

- ↑ Pratt, International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, 1:192.

- ↑ "Apostasy," 39.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 Dictionary of Biblical Imagery, 39.

- ↑ Dictionary of Biblical Imagery, 39. Paul Barnett says, "Jesus foresaw the fact of apostasy and warned both those who would fall into sin as well as those who would cause others to fall (see, e.g., Mark 9:42-49)." (Dictionary of the Later NT, 73).

- ↑ McKnight adds: "Because apostasy is disputed among Christian theologians, it must be recognized that ones overall hermeneutic and theology (including ones general philosophical orientation) shapes how one reads texts dealing with apostasy." Dictionary of Theological Interpretation of the Bible, 59.

- ↑ Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary, "Apostasy," 87.

- ↑ "Discipline That Can Yield Peaceable Fruit". The Watchtower: 26. April 15, 1988. Archived from the original on 2007-12-07.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 w06 1/15 pp. 21–25 - The Watchtower—2006

- ↑ Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 28:5 [2004], p. 42–43

- ↑ Hart, Benjamin (28 September 2011). "Jehovah's Witness Magazine Brands Defectors 'Mentally Diseased'". Huffington Post.

- ↑ From the Editors of Hinduism Today (2007). What Is Hinduism?: Modern Adventures Into a Profound Global Faith. Himalayan Academy Publications. pp. 416 pages.(see page XX and 136). ISBN 978-1-934145-00-5.

- ↑ Al-Azhar, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ↑ Heffening, W. (2012), "Murtadd." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs; Brill

- ↑ Watt, W. M. (1964). Conditions of membership of the Islamic Community, Studia Islamica, (21), pages 5–12

- ↑ Burki, S. K. (2011). Haram or Halal? Islamists' Use of Suicide Attacks as Jihad. Terrorism and Political Violence, 23(4), pages 582–601

- ↑ Rahman, S. A. (2006). Punishment of apostasy in Islam, Institute of Islamic Culture, IBT Books; ISBN 983-9541-49-8

- ↑ Mousavian, S. A. A. (2005). A DISCUSSION ON THE APOSTATE'S REPENTANCE IN SHI'A JURISPRUDENCE. Modarres Human Sciences, 8, TOME 37, pages 187–210, Mofid University (Iran).

- ↑ Advanced Islamic English dictionary Расширенный исламский словарь английского языка (2012), see entry for Fitri Murtad

- ↑ Advanced Islamic English dictionary Расширенный исламский словарь английского языка (2012), see entry for Milli Murtad

- ↑ See chapters 3, 9 and 16 of Qur'an; e.g. [Quran 3:90] * [Quran 9:66] * [Quran 16:88]

- ↑ See Sahih al-Bukhari, Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:52:260 * Sahih al-Bukhari, 9:83:17 * Sahih al-Bukhari, 9:89:271

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Saeed, A., & Saeed, H. (Eds.). (2004). Freedom of religion, apostasy and Islam. Ashgate Publishing; ISBN 0-7546-3083-8

- ↑ Paul Marshall and Nina Shea (2011), SILENCED: HOW APOSTASY AND BLASPHEMY CODES ARE CHOKING FREEDOM WORLDWIDE, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-981228-8

- ↑ Campo, Juan Eduardo (2009), Encyclopedia of Islam, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8; see page 48, 108-109, 118

- ↑ Peters, R., & De Vries, G. J. (1976). Apostasy in Islam. Die Welt des Islams, 1-25.

- ↑ Warraq, I. (Ed.). (2003). Leaving Islam: Apostates Speak Out. Prometheus Books; ISBN 1-59102-068-9

- ↑ Arzt, Donna (1995). Heroes or heretics: Religious dissidents under Islamic law, Wis. Int'l Law Journal, 14, 349-445

- ↑ Mansour, A. A. (1982). Hudud Crimes (From Islamic Criminal Justice System, P 195–201, 1982, M Cherif Bassiouni, ed.-See NCJ-87479).

- ↑ Lippman, M. (1989). Islamic Criminal Law and Procedure: Religious Fundamentalism v. Modern Law. BC Int'l & Comp. L. Rev., 12, pages 29, 263-269

- ↑ Campo, Juan Eduardo (2009), Encyclopedia of Islam, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8; see page 174

- ↑ Tamadonfar, M. (2001). Islam, law, and political control in contemporary Iran, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40(2), 205-220.

- ↑ El-Awa, M. S. (1981), Punishment in Islamic Law, American Trust Pub; pages 49–68

- ↑ Forte, D. F. (1994). Apostasy and Blasphemy in Pakistan. Conn. J. Int'l L., 10, 27.

- ↑ Ibn Warraq (2003), Leaving Islam: Apostates Speak Out, ISBN 978-1591020684, pp 1-27

- ↑ Schneider, I. (1995), Imprisonment in Pre-classical and Classical Islamic Law, Islamic Law and Society, 2(2): 157-173

- ↑ The Truth about the Alleged Punishment for Apostasy in Islam (PDF). Islam International Publications. ISBN 1-85372-850-0. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- ↑ The Truth about the Alleged Punishment for Apostasy in Islam (PDF). Islam International Publications. pp. 18–25. ISBN 1-85372-850-0.

- ↑ The Truth about the Alleged Punishment for Apostasy in Islam (PDF). Islam International Publications. p. 8. ISBN 1-85372-850-0.

- ↑ Khan, A. M. (2003), Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan: An Analysis Under International Law and International Relations, Harvard Human Rights Journal, 16, 217

- ↑ Andrew March (2011), Apostasy: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199805969

- ↑ "Muslim-Majority Countries". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ Zaki Badawi, M.A. (2003). "Islam". In Cookson, Catharine. Encyclopedia of religious freedom. New York: Routledge. pp. 204–8. ISBN 0-415-94181-4.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia: Writer Faces Apostasy Trial - Human Rights Watch". Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ The Fate of Infidels and Apostates under Islam 2005

- ↑ Freedom of Religion, Apostasy and Islam by Abdullah Saeed and Hassan Saeed (Mar 30, 2004), ISBN 978-0-7546-3083-8

- ↑ "Majorities of Muslims in Egypt and Pakistan support the death penalty for leaving Islam". Washington Post. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ The World's Muslims: Religion, Politics and Society, April 30 2013

- ↑ Stephen Bates. "More young Muslims back sharia, says poll". the Guardian. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "riddah - Islamic history". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 13:6–10

- ↑ template.htm Introduction to the Thought of Rav Kookby, Lecture #16: "Kefira" in our Day from vbm-torah.org (the Virtual Beit Midrash)

- ↑ template.htm Introduction to the Thought of Rav Kookby, Lecture #17: Heresy V from vbm-torah.org (the Virtual Beit Midrash)

- ↑ "Introduction to Sikhism | SikhNet". sikhnet.com. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ↑ Wilson, Bryan R. Apostates and New Religious Movements, Oxford, England, 1994

- ↑ Wright, Stuart, A., Exploring Factors that Shatpe the Apostate Role, in Bromley, David G., The Politics of Religious Apostasy, pp. 95–114, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7

- ↑ Bromley David G. et al., The Role of Anecdotal Atrocities in the Social Construction of Evil,

- ↑ in Bromley, David G et al. (ed.), Brainwashing Deprogramming Controversy: Sociological, Psychological, Legal, and Historical Perspectives (Studies in religion and society) p. 156, 1984, ISBN 0-88946-868-0

- ↑ Bromley, David G. (ed.); Richardson, James T. (1998). "Apostates Who Never Were: The Social Construction of Absque Facto Apostate Narratives". in The politics of religious apostasy: the role of apostates in the transformation of religious movements. New York: Praeger. pp. 134–5. ISBN 0-275-95508-7.

- ↑ Kliever 1995 Kliever. Lonnie D, Ph.D. The Reliability of Apostate Testimony About New Religious Movements, 1995.

- ↑ "Melton 1999"Melton, Gordon J., Brainwashing and the Cults: The Rise and Fall of a Theory, 1999.

- ↑ Wilson, Bryan R. (Ed.) The Social Dimensions of Sectarianism, Rose of Sharon Press, 1981.

- ↑ Beit-Hallahmi 1997 Beith-Hallahmi, Benjamin Dear Colleagues: Integrity and Suspicion in NRM Research, 1997.

- ↑ "< Lucas, Phillip Charles Ph.D. – Profile". Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "Holy Order of MANS". Archived from the original on 11 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- ↑ Lucas 1995 Lucas, Phillip Charles, From Holy Order of MANS to Christ the Savior Brotherhood: The Radical Transformation of an Esoteric Christian Order in Timothy Miller (ed.), America's Alternative Religions State University of New York Press, 1995

- ↑ Duhaime, Jean (Université de Montréal) Les Témoignages de convertis et d'ex-adeptes (English: The testimonies of converts and former followers, in Mikael Rothstein et al. (ed.), New Religions in a Postmodern World, 2003, ISBN 87-7288-748-6

- ↑ "The Culture of Cults". ex-cult.org. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ↑ Dunlop 2001 The Culture of Cults

- ↑ The Two "Camps" of Cultic Studies: Time for a Dialogue Langone, Michael, Cults and Society, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2001

- ↑ Zablocki 1996 Zablocki, Benjamin, Reliability and validity of apostate accounts in the study of religious communities. Paper presented at the Association for the Sociology of Religion in New York City, Saturday, August 17, 1996.

- ↑ Bromley, David G. (ed.); Richardson, James T. (1998). "Apostates, Whistleblowers, Law, and Social Control". in The politics of religious apostasy: the role of apostates in the transformation of religious movements. New York: Praeger. p. 171. ISBN 0-275-95508-7.

Some of those who leave, whatever the method, become "apostates" and even develop into "whistleblowers", as those terms are defined in the first chapter of this volume.

- ↑ Bromley, David G. (ed.); Richardson, James T. (1998). "Apostates, Whistleblowers, Law, and Social Control". in The politics of religious apostasy: the role of apostates in the transformation of religious movements. New York: Praeger. pp. 185–186. ISBN 0-275-95508-7.

- ↑ Bromley, David G. (ed.); Richardson, James T. (1998). "Apostasy and the Management of Spoiled Identity". in The politics of religious apostasy: the role of apostates in the transformation of religious movements. New York: Praeger. pp. 185–186. ISBN 0-275-95508-7.

- ↑ Introvigne 1997

- ↑ Burks, Ronald, Cognitive Impairment in Thought Reform Environments

- ↑ Hadden, J and Bromley, D eds. (1993), The Handbook of Cults and Sects in America. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, Inc., pp. 75–97.

- ↑ F. Derks and the professor of psychology of religion Jan van der Lans The post-cult syndrome: Fact or Fiction?, paper presented at conference of Psychologists of Religion, Catholic University Nijmegen, 1981, also appeared in Dutch language as Post-cult-syndroom; feit of fictie?, published in the magazine Religieuze bewegingen in Nederland/Religious movements in the Netherlands nr. 6 pages 58–75 published by the Free university Amsterdam (1983)

- ↑ Report of the Swedish Government's Commission on New Religious Movements (1998), 1.6 The need for support (Swedish), English translation

The great majority of members of the new religious movements derive positive experience from their membership. They have subscribed to an idea or doctrine which corresponds to their personal needs. Membership is of limited duration in most cases. After two years, the majority have left the movement. This withdrawal is usually quite undramatic, and the people withdrawing feel enriched by a predominantly positive experience. The Commission does not recommend that special resources be established for the rehabilitation of withdraws. The cases are too few in number and the problem picture too manifold for this: each individual can be expected to need help from several different care providers or facilitators. - ↑ Banks, Adelle M. (2011-09-28). "Iranian Pastor Youcef Nadarkhani's potential execution rallies U.S. Christians". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2011-10-07. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

Religious freedom advocates rallied Wednesday (Sept. 28) around an Iranian pastor who was facing execution because he had refused to recant his Christian faith in the overwhelmingly Muslim country.

- ↑ Abdelaziz, Salma (2013-12-25). "Wife: Saudi blogger sentenced to death for apostasy". CNN (NYC).

- ↑ Sudanese woman convicted CNN (May 2014)

- ↑ Open letter by Ayaan Hirsi Ali published on the website of the Nederlandse Omroep Stichting dated 3 November 2004

English translation: "Theo's naivety was not that it could not happen here, but that it could not happen to him. He said, "I am the local fool; they won't harm me. But you should be careful. You are the apostate.""

Dutch original "Theo's naïviteit was niet dat het hier niet kon gebeuren, maar dat het hem niet kon gebeuren. Hij zei: "Ik ben de dorpsgek, die doen ze niets. Wees jij voorzichtig, jij bent de afvallige vrouw." " - ↑ Taslima's Pilgrimage Meredith Tax, from The Nation

- ↑ McCarthy, Rory (2001-08-20). "Blasphemy doctor faces death". The Guardian (London).

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Bromley, David G. 1988. Falling From the Faith: The Causes and Consequences of Religious Apostasy. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Dunlop, Mark, The culture of Cults, 2001

- Introvigne, Massimo Defectors, Ordinary Leavetakers and Apostates: A Quantitative Study of Former Members of New Acropolis in France – paper delivered at the 1997 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Religion, San Francisco, November 23, 1997

- The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906). The Kopelman Foundation.

- Lucas, Phillip Charles, The Odyssey of a New Religion: The Holy Order of MANS from New Age to Orthodoxy Indiana University press;

- Lucas, Phillip Charles, Shifting Millennial Visions in New Religious Movements: The case of the Holy Order of MANS in The year 2000: Essays on the End edited by Charles B. Strozier, New York University Press 1997;

- Lucas, Phillip Charles, The Eleventh Commandment Fellowship: A New Religious Movement Confronts the Ecological Crisis, Journal of Contemporary Religion 10:3, 1995:229–41;

- Lucas, Phillip Charles, Social factors in the Failure of New Religious Movements: A Case Study Using Stark's Success Model SYZYGY: Journal of Alternative Religion and Culture 1:1, Winter 1992:39–53

- Wright, Stuart A. 1988. "Leaving New Religious Movements: Issues, Theory and Research," pp. 143–165 in David G. Bromley (ed.), Falling From the Faith. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Wright, Stuart A. 1991. "Reconceptualizing Cult Coercion and Withdrawal: A Comparative Analysis of Divorce and Apostasy." Social Forces 70 (1):125–145.

- Wright, Stuart A. and Helen R. Ebaugh. 1993. "Leaving New Religions," pp. 117–138 in David G. Bromley and Jeffrey K. Hadden (eds.), Handbook of Cults and Sects in America. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Zablocki, Benjamin et al., Research on NRMs in the Post-9/11 World, in Lucas, Phillip Charles et al. (ed.), NRMs in the 21st Century: legal, political, and social challenges in global perspective, 2004, ISBN 0-415-96577-2

- Testimonies, memoirs, and autobiographies

- Babinski, Edward (editor), Leaving the Fold: Testimonies of Former Fundamentalists. Prometheus Books, 2003. ISBN 1-59102-217-7; ISBN 978-1-59102-217-6

- Dubreuil, J. P. 1994 L'Église de Scientology. Facile d'y entrer, difficile d'en sortir. Sherbrooke: private edition (ex-Church of Scientology)

- Huguenin, T. 1995 Le 54e Paris Fixot (ex-Ordre du Temple Solaire who would be the 54th victim)

- Kaufmann, Inside Scientology/Dianetics: How I Joined Dianetics/Scientology and Became Superhuman, 1995

- Lavallée, G. 1994 L'alliance de la brebis. Rescapée de la secte de Moïse, Montréal: Club Québec Loisirs (ex-Roch Thériault)

- Pignotti, Monica, My nine lives in Scientology, 1989,

- Wakefield, Margery, Testimony, 1996

- Lawrence Woodcraft, Astra Woodcraft, Zoe Woodcraft, The Woodcraft Family, Video Interviews

- Writings by others

- Carter, Lewis, F. Lewis, Carriers of Tales: On Assessing Credibility of Apostate and Other Outsider Accounts of Religious Practices published in the book The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Apostates in the Transformation of Religious Movements edited by David G. Bromley Westport, CT, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7

- Elwell, Walter A. (Ed.) Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible, Volume 1 A–I, Baker Book House, 1988, pages 130–131, "Apostasy". ISBN 0-8010-3447-7

- Malinoski, Peter, Thoughts on Conducting Research with Former Cult Members , Cultic Studies Review, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2001

- Palmer, Susan J. Apostates and their Role in the Construction of Grievance Claims against the Northeast Kingdom/Messianic Communities

- Wilson, S.G., Leaving the Fold: Apostates and Defectors in Antiquity. Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2004. ISBN 0-8006-3675-9; ISBN 978-0-8006-3675-3

- Wright, Stuart. "Post-Involvement Attitudes of Voluntary Defectors from Controversial New Religious Movements". ''Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 23 (1984):172–182.

External links

| Look up apostasy in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Laws Criminalizing Apostasy, Library of Congress (overview of the apostasy laws of 23 countries in Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia)