Apis florea

| Apis florea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Worker | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Apidae |

| Genus: | Apis |

| Subgenus: | (Micrapis) |

| Species: | A. florea |

| Binomial name | |

| Apis florea Fabricius, 1787 | |

| |

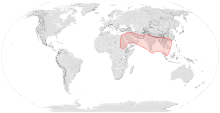

| Range of Apis florea | |

The dwarf honey bee (or red dwarf honey bee), Apis florea, is one of two species of small, wild honey bees of southern and southeastern Asia. It has a much wider distribution than its sister species, Apis andreniformis.

This species, together with A. andreniformis, is the most plesiomorphic honeybee species alive. Separating roughly about the Bartonian (some 40 Mya or slightly later) from the other lineages, they do not seem to have diverged from each other a long time before the Neogene.[2]

These two species together comprise the subgenus Micrapis, and are the most primitive of the living species of Apis, reflected in their small colony size, and simple nest construction. The exposed single combs are built on branches of shrubs and small trees. The forager bees do not perform a gravity-oriented waggle dance on the vertical face of the comb to recruit nestmates as in the domesticated Apis mellifera and other species. Instead, they perform the dance on the horizontal upper surface where the comb wraps around the supporting branch. The dance is a straight run pointing directly to the source of pollen or nectar the forager has been visiting. In all other Apis species, the comb on which foragers dance is vertical, and the dance is not actually directed towards the food source.

Both the bees were generally identified as Apis florea, and most information still relates to this species prior to the 1990s. However, the distinctiveness of the two species A. florea and A. andreniformis was established unequivocally in the 1990s. A. florea is redder and the first abdomen is always red in an old worker (younger workers are paler in colour, as is the case in giant honey bees); A. andreniformis is in general darker and the first abdomen segment is totally black in old bees.[3]

Habitat and Nesting

Apis Florea are found in southeastern Asian countries, especially in Thailand, Iran, Oman, India, Myanmar, and some part of china, Cambodia, and Vietnam. They live in forest habitat but they are also the tropical fruit crops pollinators in Thailand. [4] Apis Florea have their nests exposed; it’s always a single comb on a single branch. If they are building new nest near to the old one, they salvage the wax from the old nest. Other species of honeybee do not return to the old nest to the salvage wax. This behavior is only observed in this species. [5]Even within the species this behavior differs, the colonies that migrate less than 200 meters involve in the salvaging of the wax, but the colonies that migrate long distance do not return back for the old wax.[6]

Genetic Diversity

Even in a single nest there is high genetic diversity among the Apis Florea bees. Since Honey bee queens are polygamous, as a result vast genetic variability occurs. The inclination of this species towards performing certain tasks depends upon the genetic variance. Within the species there are colonies performing specific tasks and behaving in a specific way. For example fanning of the nest is done by specific colony, when the nest reaches some temperature threshold.[7]

Division of Labor

Apis Floreas’ younger ones work within the nests, they do maintenance; older ones are responsible for protection and foraging. Some specific tasks like fanning of comb to have stable temperature are done by specific colony, which is genetically motivated. It is done by patrilines, this is because different patrilines respond to different temperature threshold.[8]

Migration

Apis Floera can expand to totally new place, through human introduction or itself. It can pose threat to native insect like Apis. mellifera because they compete with same resources.[9]

Ecology

Aside from their small size, simple exposed nests, and simplified dance language, the lifecycle and behaviour of this species is fairly similar to other species of Apis. Workers of A. florea, like those of the species A. mellifera, also engage in worker policing, a process where nonqueen eggs are removed from the hive.

Queenless A. florea colonies have been observed to merge with nearby queen-right A. florea colonies, suggesting workers are attracted to queen bee pheromones.[10]

Parasites

The main parasites of both A. andreniformis and A. florea belong to the mite genus Euvarroa. However, A. andreniformis is attacked by the species Euvarroa wongsirii, while Euvarroa sinhai preys on A. florea and colonies of imported A. mellifera. The two species of Euvarroa have morphological and biological differences: while E. wongsirii has a triangular body shape and a length of 47–54 μm, E. sinhai has a more circular shape and a length of 39–40 μm.

References

- ↑ Duangphakdee, Orawan; Nikolaus Koenigerb, Gudrun Koenigerb, Siriwat Wongsiria and Sureerat Deowanish (October–December 2005). "Reinforcing a barrier – a specific social defense of the dwarf honeybee (Apis florea) released by the weaver ant (Oecophylla smaragdina)". Apidologie 36 (4): 505–511. doi:10.1051/apido:2005036.

- ↑ Maria C. Arias & Walter S. Sheppard (2005). "Phylogenetic relationships of honey bees (Hymenoptera:Apinae:Apini) inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequence data". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 37 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.02.017. PMID 16182149.

Maria C. Arias & Walter S. Sheppard (2005). "Corrigendum to "Phylogenetic relationships of honey bees (Hymenoptera:Apinae:Apini) inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequence data" [Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 37 (2005) 25–35]". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 40 (1): 315. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.02.002. - ↑ Y. R. Wu & B. Kuang (1987). "Two species of small honeybee - a study of the genus Micrapis". Bee World 68: 153–155.

- ↑ Deowanish, S., et al. "Biodiversity of dwarf honey bees in Thailand." Proc. 7th Int. Conf. Trop. Bees, Chiang Mai, Thailand. 2001.

- ↑ Hepburn, Randall, et al. "Comb Wax Salvage by the Red Dwarf Honeybee, Apis Florea F." Journal of Insect Behavior 23.2 (2010): 159-64. ProQuest. Web. 28 Mar. 2015.

- ↑ Pirk, Christian W., et al. "Economics of Comb Wax Salvage by the Red Dwarf Honeybee, Apis Florea." Journal of Comparative Physiology.B, Biochemical, Systemic, and Environmental Physiology 181.3 (2011): 353-9. ProQuest. Web. 28 Mar. 2015.

- ↑ Jones, Julia C., Piyamas Nanork, and Benjamin P. Oldroyd. "The Role of Genetic Diversity in Nest Cooling in a Wild Honey Bee, Apis Florea." Journal of Comparative Physiology 193.2 (2007): 159-65. ProQuest. Web. 28 Mar. 2015

- ↑ Beshers, Samuel N., and Jennifer H. Fewell. "Models of Division of Labor in Social Insects." Annual Review of Entomology 46 (2001): 413. ProQuest. Web. 28 Mar. 2015.

- ↑ Moritz, Robin F., et al. "Invasion of the Dwarf Honeybee Apis Florea into the Near East." Biological Invasions 12.5 (2010): 1093-9. ProQuest. Web. 17 Apr. 2015.

- ↑ Wongvilas, S., et al. "Interspecific and conspecific colony mergers in the dwarf honey bees Apis andreniformis and A. florea." Insectes Sociaux 57.3 (2010): 251-255.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apis florea. |