Apis dorsata

| Giant honey bee | |

|---|---|

| |

| Close-up of workers on comb | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Apidae |

| Genus: | Apis |

| Subgenus: | (Megapis) |

| Species: | A. dorsata |

| Binomial name | |

| Apis dorsata Fabricius, 1793 | |

| |

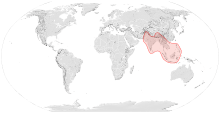

| Range of A. dorsata | |

Apis dorsata, the giant honey bee, is a honey bee of South and Southeast Asia, mainly in forested areas such as the Terai of Nepal and sometime even in Malaysia and Singapore. The subspecies with the largest individuals is the Himalayan cliff honey bee — A. d. laboriosa — but typical A. dorsata workers from other subspecies are around 17–20 mm (0.7–0.8 in) long.

_on_Tribulus_terrestris_W_IMG_1020.jpg)

Nests are mainly built in exposed places far off the ground, on tree limbs and under cliff overhangs, and sometimes on buildings. A. dorsata is a defensive bee and has never been domesticated (as it does not use enclosed cavities for nesting). Each colony consists of a single vertical comb (sometimes approaching 1 m2) suspended from above, and the comb is typically covered by a dense mass of bees in several layers. When disturbed, the workers may exhibit a defensive behavior known as defense waving. Bees in the outer layer thrust their abdomens 90° in an upward direction and shake them in a synchronous way. This may be accompanied by stroking of the wings. The signal is transmitted to nearby workers that also adopt the posture, thus creating a visible — and audible — "ripple" effect across the face of the comb, in an almost identical manner to an audience wave at a crowded stadium.

These bees are tropical and in most places they migrate seasonally. Some recent evidence indicates the bees return to the same nest site, though most, if not all, of the original workers might be replaced in the process. The mechanism of memory retention remains a mystery.

Indigenous peoples have traditionally used this species as a source of honey and beeswax, a practice known as honey hunting.

Subspecies

Michael S. Engel recognized the following subspecies:[1]

- A. d. dorsata primarily from India

- A. d. binghami Cockerell; from Malaysia and Indonesia

- A. d. breviligula Maa; from the Philippines

- A. d. laboriosa Fabricius; (Himalayan cliff honey bee), also in Myanmar, Laos, and southern China

The latter is not distinct morphologically from the nominate subspecies, but has different housekeeping and swarming behavior, allowing it to survive at high altitudes. In addition, little gene flow has occurred between A. dorsata and it for millions of years; accordingly, some argue it should be classified as a species.[2] Likewise, the southeastern taxon A. d. binghami seems also to be distinct. The limits of their ranges in Indochina and the possible distinctness of the geographically distant Philippines population require more study.[2] However, the use of the taxonomic rank of "subspecies" is typical for geographically discrete populations, so the difference in opinion here is whether or not to recognize the rank of subspecies or not (i.e., no one is disputing they are distinct lineages, the dispute is over whether to call them "species").

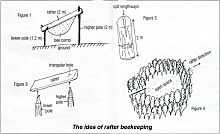

Rafter beekeeping

In some Melaleuca forests of southern Vietnam, people use a traditional method of collecting honey and wax from A. dorsata colonies. This method of “rafter beekeeping” was first reported in 1902.[3]

According to Vietnamese sociologists, in the early 19th century, honey hunting or raftering was the most important occupation of the people who lived in the Melaleuca forest swamp. At that time, people paid taxes to the government in exchange for living in the forest. Beeswax was used to pay the tax and for making candles, and was sold to visiting ships from Hainan, China.[4][5]

Between 1945 and 1975, the forests were devastated first by wars, and then by forest clearing for wood and agricultural purposes. As a consequence, rafter beekeeping dramatically decreased in the area. The technique is still used today at the state farm of Song Trem in U Minh District. According to a survey, about 96 beekeepers are in the area. In 1991, they harvested 16,608 l of honey and 747 kg of wax.[6]

Attacks on humans

At least one fatal defensive attack on a human has been reported.[7]

References

- ↑ Michael S. Engel (1999). "The taxonomy of recent and fossil honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Apis)". Journal of Hymenoptera Research 8: 165–196.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Maria C. Arias & Walter S. Sheppard (2005). "Phylogenetic relationships of honey bees (Hymenoptera:Apinae:Apini) inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequence data". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 37 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.02.017. PMID 16182149.

Maria C. Arias & Walter S. Sheppard (2005). "Corrigendum to "Phylogenetic relationships of honey bees (Hymenoptera:Apinae:Apini) inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequence data" [Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 37 (2005) 25–35]". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 40 (1): 315. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.02.002. - ↑ Fougères, M. (1902). Rapport sur l’apiculture coloniale. III Congrès Internationale l’apiculture pp. 53–58.

- ↑ Dau, Nguyen Dinh. 1992. Personal communication.

- ↑ Son Nam. 1993. (reprint) Dat Gia dinh xua (The ancient Southern part). Ho Chi Minh City Publishing House, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam.

- ↑ Phung Huu Chinh, Nguyen Hung Minh, Pham Hong Thai and Nguyen Quang Tan (1995). Rafter Beekeeping in Melaleuca Forests in Vietnam. Bees for Development Journal 36 pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Chong, Elena (April 29, 2014). "Death of man stung by bees ruled accidental". The Straits Times. Retrieved April 30, 2014.