Apayao

| Apayao | ||

|---|---|---|

| Province | ||

| ||

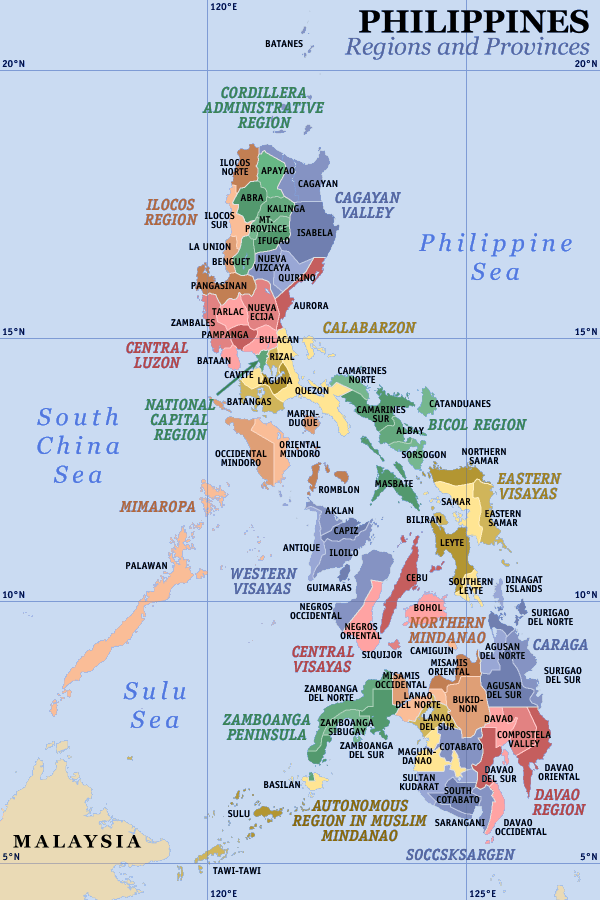

Location in the Philippines | ||

| Coordinates: 17°45′N 121°15′E / 17.750°N 121.250°ECoordinates: 17°45′N 121°15′E / 17.750°N 121.250°E | ||

| Country | Philippines | |

| Region | Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) | |

| Founded | February 14, 1995 | |

| Capital | Kabugao* | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Province of the Philippines | |

| • Governor | Elias C. Bulut, Jr. (Liberal Party) | |

| • Congresswoman | Eleanor C. Bulut-Begtang (Nationalist People's Coalition) | |

| • Vice Governor | Hector Pascua (Liberal Party) | |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Total | 4,413.35 km2 (1,704.00 sq mi) | |

| Area rank | 29th out of 81 | |

| Population (2010)[2] | ||

| • Total | 112,636 | |

| • Rank | 78th out of 81 | |

| • Density | 26/km2 (66/sq mi) | |

| • Density rank | 81st out of 81 | |

| Divisions | ||

| • Independent cities | 0 | |

| • Component cities | 0 | |

| • Municipalities | 7 | |

| • Barangays | 133 | |

| • Districts | Lone district of Apayao | |

| Time zone | PHT (UTC+8) | |

| ZIP code | 3807 to 3814 | |

| Dialing code | 74 | |

| ISO 3166 code | PH-APA | |

| Spoken languages | Ilocano, Isnag (Ymandaya, Imallod and Dibagat-kabugao), Tagalog, English | |

| Website |

www | |

| * Kabugao is the officially-recognized capital and seat of government, although the province carries out many of its operations in a new government center established in Luna. | ||

Apayao (Ilokano: Probinsya ti Apayao, Tagalog: Lalawigan ng Apayao), is a landlocked province of the Philippines in the Cordillera Administrative Region in Luzon. Its capital town is Kabugao.

The province borders Cagayan to the north and east, Abra and Ilocos Norte to the west, and Kalinga to the south. Prior to 1995, Kalinga and Apayao comprised a single province named Kalinga-Apayao, which was partitioned to better service the needs of individual ethnic groups.

With a population of 112,636 (as of 2010)[3] covering an area of 4413.35 square kilometers,[1] Apayao is the least densely-populated province in the Philippines.

Gallery

-

Native Dibagat homes

-

Dibagat River

History

Spanish period

Although Apayao, which was then part of Cagayan,[4] was among the earliest areas penetrated by the Spaniards in the Cordilleras, the region, inhabited by the Isneg tribe, remained largely outside Spanish control until late in the 19th century. As early as 1610, the Dominican friars established a mission in what is now the town of Pudtol. In 1684, the friars again made attempts to convert the people and established a church in what is now Kabugao.

The Spanish authorities were then able to establish in Cagayan the comandancias of Apayao and Cabugaoan in 1891,[4][5][6] which covered the western and eastern portions of what is now Apayao. The comandancias, however, failed to bring total control and the Spanish government only maintained a loose hold over the area.

American period

The Americans established the Mountain Province on August 13, 1908, with the enactment of Act No. 1876. Apayao, along with Amburayan, Benguet, Bontoc, Ifugao, Kalinga, and Lepanto, became sub-provinces of this new province.[5][6][7]

World War II

In 1942, Japanese Imperial forces entered Apayao, starting a three-year occupation of the province during the Second World War. Local Filipino troops of the 1st, 2nd, 12th, 15th and 16th Infantry Division of the Philippine Commonwealth Army and the military forces of the USAFIP-NL 11th and 66th Infantry Regiment, supported by the Cordilleran guerrillas, drove out the Japanese in 1945.

Kalinga-Apayao

On June 18, 1966, the huge Mountain Province was split into four provinces with the enactment of Republic Act No. 4695. The four provinces were Benguet, Bontoc (renamed Mountain Province), Kalinga-Apayao and Ifugao.[6][8] Kalinga-Apayao, along with Ifugao, became one of the provinces of the Cagayan Valley region in 1972.[8]

On July 15, 1987, the Cordillera Administrative Region was established and Kalinga-Apayao was made one of its provinces.[6][8][9][10]

Kalinga-Apayao splitting

Finally, on February 14, 1995, Kalinga-Apayao was split into two distinct provinces with the passage of Republic Act No. 7878.[6][8][11]

The merged outlines of Apayao and Kalinga resemble a bust of a man akin to former President Ferdinand Marcos (looking toward his home province, Ilocos Norte) whom the media called as the "Great Profile" during the Marcos Era.

Geography

Physical

Apayao is basically on a mountainous area traversed by many rivers. Region I, II and other provinces assemble its boundaries. Plains and valleys are used for farming. Apayao is basically composed of farmlands.

Administrative

Apayao is subdivided into 7 municipalities, all of which belong a lone legislative district.[3][12]

Table Legend:

† Provincial capital

| Municipality | Legislative district[12] | Land area (km2)[12] | Population (2010)[3] | Pop. density (per km2) | No. of barangays | ZIP code | Income class[12] | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

||||||||

| Calanasan (Bayag) | lone | 1,256.15 | 11,568 | 9.2 | 20 | 3814 | 1st |  |

| Conner | lone | 694.30 | 24,811 | 36 | 21 | 3807 | 2nd |  |

| Flora | lone | 324.40 | 16,743 | 52 | 16 | 3810 | 3rd |  |

| Kabugao † | lone | 935.12 | 16,170 | 17 | 21 | 3809 | 1st |  |

| Luna (Macatel) | lone | 606.04 | 18,029 | 30 | 22 | 3813 | 3rd |  |

| Pudtol | lone | 401.02 | 13,305 | 33 | 22 | 3812 | 4th |  |

| Santa Marcela | lone | 196.32 | 12,010 | 61 | 13 | 3811 | 5th |  |

| Apayao Total | lone | 4,413.35 | 112,636 | 26 | 133 | 3807 - 3814 | 3rd[12] | |

*Note: Italicized names are former names.

Barangays

The 7 municipalities of the province comprise a total of 133 barangays, with Poblacion in Kabugao as the most populous in 2010, and Eleazar in Calanasan as the least.[3][12]

Climate

The prevailing climate in the province falls under Corona's Type III Classification. It is characterized by relatively dry and wet seasons, from November to April, and wet during the rest of the year. Heaviest rain occurs during December to February while the month of May is the warmest.

Demographics

| Population census of Apayao | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1990 | 74,720 | — |

| 1995 | 83,660 | +2.14% |

| 2000 | 97,129 | +3.25% |

| 2007 | 103,633 | +0.90% |

| 2010 | 112,636 | +3.08% |

| Source: National Statistics Office[2] | ||

Based on the 2000 census survey, half of the population is Ilocano 50.82% and almost 1/3 of the population is Isnag 29.95%. Other ethnic groups living in the province are the Malaueg 3.69%, Isneg 3.48%, Kalinga 3.08%, Ibaloi 1.01%, Kankana-ey 1.24% and Bontok 1.04%.[13]

People and culture

The Isneg, also Isnag or Apayao, live at the northwesterly end of northern Luzon, in the upper half of the Cordillera province of Apayao. The term “Isneg” derives from a combination of “is” meaning “recede” and “uneg” meaning “interior.” Thus, it means “people who have gone into the interior.” In Spanish missionary accounts, they, together with the Kalinga and other ethnic groups between the northern end of the Cagayan Valley and the northeastern part of the Ilocos, were referred to as “los Apayaos,” an allusion to the river whose banks and nearby rugged terrain were inhabited by the people. They were also called “los Mandayas,” a reference to an Isneg word meaning “upstream.” The term “Apayao” has been used interchangeably with “Isneg,” after the name of the geographical territory which these people have inhabited for ages. This is inaccurate, however, because the subprovince of Apayao is not exclusively peopled by the Isneg.

There has been a large influx of Ilocano over the years. From Cagayan, the Itawes have occupied the eastern regions. The Aeta inhabit the northern and northeastern parts of the province. There are the Kalinga, the other major group in the province. The Isneg have always built their settlements on the small hills that lie along the large Apayao-Abulog river of the province. In 1988, the Isneg were estimated to number around 45,000. Municipalities occupied by the Isneg include Pudtol, Kabugao, Kalanasan and Conner (Peralta 1988:1).

Two major river systems, the Abulog and the Apayao, run through Isneg country, which until recent times has been described as a region of “dark tropical forests,” and endowed with other natural resources. In one early account, the Isneg were described as of slender and graceful stature, with manners that were kindly, hospitable, and generous, possessed with the spirit of self-reliance and courage, and clearly artistic in their temperament.

The Isneg’s ancestors are believed to have been the proto-Austronesians who came from South China thousands of years ago. Later, they came in contact with groups practicing jar burial, from whom they adopted the custom. They later also came into contact with Chinese traders plying the seas south of the Asian mainland. From the Chinese they bought the porcelain pieces and glass beads which now form part of the Isneg’s priceless heirlooms. The Isneg have been known to be a headtaking society since recorded history. The Isneg’s main staple is rice, which they have traditionally produced in abundance. This is raised through slash-and-burn agriculture. There has always been a surplus every year, except in rare instances of drought or pest infestation.

According to Isneg traditional view, the ownership of land is absolute, governed by an unwritten law of property relations. This law is respected and recognized, enforced and defended by generations of Isneg. Life is materially associated with the land, the forests, and the rivers. The recognized owner of a piece of land has exclusive rights over its natural resources and its fruits.

According to Isneg custom law, land is acquired and owned through: first-use (pioneer principle); actual possession and active occupation; and inheritance. The land that an individual or clan can own through the first-use or pioneer principle are: the bannuwag (swidden); the sarra or ngnganupan (forest and hunting grounds); and the usat or angnigayan (water and aquatic resources). Part of the land that can also be claimed for ownership is the land space called nagbabalayan (from balay, which means “house”) where the owner or his family and clan have resided in the past, and which they have planted to coconut, palm, and fruit trees. Land acquired through possession and occupation include the swidden farm, residential land, and fishing grounds. All these categories of land can also be acquired through tawid (inheritance).Isneg society did not develop a form of village leadership strong enough to be recognized as an indigenous political authority by all Isneg communities in the region. A possible reason for this failure is the small size of villages or hamlets, and thus the small population of males that could be harnessed to form an army strong enough to bring other villages under its control.

For ages, Isneg warriors engaged in small-scale ambuscades, and not in full-blown tribal war. The taking of a few heads during a raid was in retaliation for some previous wrong or misdeed, and not for the conquest of territory. Slavery was unknown, so there was no need to capture people.The Isneg hamlet may have brave men called mengal, one of whom may later become kamenglan, the bravest of the brave—the ultimate goal of a human being. The mengal also acts as arbiter of disputes. In the settlement of cases, jars, beads, rice, and animals are used to pay fines or damages. The mengal truly enjoys enormous prestige, being a warrior of proven courage. In the past, the mengal wore a red scarf around his head. His arms and shoulders were tattooed, to signify that he had taken several enemy heads in battle. The leader usually provided the sayam for his people, a lavish feast during which he was expected to recount his martial exploits. The mengal is usually one who has reached a very mature age, and having been acknowledged as the village leader, he assumes his place among the Isneg council of veterans like himself (Casal 1986:56).

The spiritual world of the Isneg is populated by more than 300 anito or spirits who assume various forms. There are no gods or hierarchical deities in the otherworld of the Isneg, only good or bad spirits.

The chief spirits are: Anlabban, who looks after the general welfare of the people and is recognized as the special protector of hunters; Bago, the spirit of the forest; and Sirinan, the river spirit. They may take the form of human beings, former mortals who mix with the living, reside in bathing places, and so on. They may be animals, with the features of a carabao, for example, and live in a cave under the water. They may be giants who live somewhere in the vicinity of Abbil. They may be spirits guarding the foot and center of the ladder going up the skyworld, seeing to it that mortals do not ascend this ladder. Most of these spirits, however, are the souls of mortals and exhibiting human traits when living as mortals. Some spirits can bring hardship into the life of the Isneg. One such spirit is Landusan, who is held responsible for some cases of extreme poverty. Those believed to be suffering from the machinations of this spirit are said to be malandusan (impoverished). But the Isneg are not entirely helpless against these scheming spirits. They can arm themselves with a potent amulet bequeathed to mortals by the benevolent spirits. This amulet is a small herb called tagarut, which grows in the forest but is hard to find.At harvest time, a wide assortment of male and female spirits attend to the activities of the Isneg, performing either good or bad works which affect the lives of people. There are spirits who come to help the reapers in gathering the harvest. They are known as Abad, Aglalannawan, Anat, Binusilan, Dawiliyan, Dekat, Dumingiw, Imbanon, Gimbanonan, Ginalinan, Sibo, and a group of sky dwellers collectively known as the llanit. On the other hand, there are spirits who prefer to cause harm rather than help with the harvest. These are Alupundan, who causes the reapers’ toes to get sore all over and swell; Arurin, who sees to it that the harvest is bad, if the Isneg farmers fail to give this female deity her share; Dagdagamiyan, a female spirit who causes sickness in children for playing in places where the harvest is being done; Darupaypay, who devours the palay stored in the hut before it is transferred to the granary; Ginuudan, who comes to measure the containers of palay, and causes it to dwindle; Sildado (from soldado or soldier), who resembles a horse, and kills children who play noisily outside the house; and Inargay, who kills people during harvest time. When inapugan, a ritual plant, is offered to Inargay, the following prayer is recited by the Isneg farmer: “Iapugko iyaw inargay ta dinaami patpatay” (I offer this betel to you, Inargay, so that you may not kill us) (Vanoverbergh 1941:337-339).

Unlike other groups, the Isneg have no traditional or indigenous knowledge of cloth weaving or pottery making. Instead, they have procured articles of clothing, pots, and other materials from the lowland Ilocano traders, in exchange for their honey, beeswax, rope, baskets, and mats (Wilson 1967:10).

Nevertheless, Isneg women have been known to favor colorful garments as their traditional costume. These consist of both small and large aken, a wraparound piece of cloth. The small version is for everyday use, while the large one is for ceremonial occasions. They also wear the badio, a short-waisted, long-sleeved blouse which is either plain or heavily embroidered; a square head scarf; and sometimes a piece of cloth around 2 meters long, worn around the waist and which serves as a carrier for small articles. The usual colors for these articles of clothing are blue and its various shades often with narrow stripes in red and white.

Menfolk, on the other hand, have a traditional dress of dark-colored (often plain blue) G-string called abag. On special occasions, this is adorned with an iput, a lavishly colored tail attached to the back end, which generally consists of a thick tuft of long fringes. They wear an upper garment called bado, which has long sleeves and reaches down to the waist. The colors are usually grayish blue, although sometimes the Isneg also wear them in red and dark blue, occasionally black or purple. Isneg men also sport the sipatal, a breastpiece indicating one’s social status (Reynolds and Grant 1973:98-99; Vanoverbergh 1929:225).

The only decorative art that the Isneg have developed from earliest times is tattooing. There are names for the various types of tattoos. There are tattoos for men and tattoos for women. Isneg males tattoo their forearms down to the wrist and the middle part of the back of their hands. This basic type is called hisi, generally black in color, and of no particular design. The andori is the more ornate type, which appears on one or both arms, on the inside. It begins from the wrist and runs all the way to the biceps and the shoulders. The design is composed of mainly wedges, diamonds, and angular lines. The andori used to symbolize the status of an Isneg male who had killed any number of enemies. The more he killed, the longer the andori on his arms. This type is largely gone now, having been associated with the practice of headtaking. Another type is the babalakay (spider), which is tattooed in front of one or both of a man’s thighs. This is either a cross-shaped figure with twiglike extensions at the ends, or several lines radiating from a small imaginary circle, suggesting an arachnid but also rather sunlike in appearance. The women decorate themselves with one of three types of tattooing. One is the andori, which the Isneg woman is allowed to have on her arms if her father has killed any number of enemies in battle. She may have the balalakat tattoo on her throat and on either or both of her thighs, sometimes also on her forearm. Or it may be the tutungrat, a series of broken lines at the back of her hands, sometimes accompanied by some dots or short, parallel straight lines tattooed at the back of her fingers (Vanoverbergh 1929:228-232).

Economy

Apayao is devoted to agricultural production, particularly food and industrial crops such as palay, corn, coffee, root crops and vegetables. Main fruits produce are lanzones, citrus, bananas and pineapples. Rice production totals 42,602 metric tons annually, as food crops totals 96,542 metric tons.

Economic activity is also based on livestock and poultry breeding such as swine, carabao, cattle, goat and sheep. Other additional investment includes manufacturing, food processing, furniture, crafts and house wares making.

Updated records of the Department of Trade and Industry Provincial Office reveal that existing industries in the province are furniture, garment craft, food processing, gifts and house wares, and agricultural support.

Festivals

- Say-Am Festival

- Say-am Festival of Apayao which is celebrated every February 14. It is in celebration of the founding anniversary of the province and Isnag’s grandest feast or celebration. A feast featuring and ushering the traditional way of Isnag’s thanksgiving to the Higher Supreme unseen being called “ALAWAGAN” executed and commenced through rituals spiced with pep songs, native chants and dances called the “TALIP and TAD-DO”. The holding and celebration of Say-am in the older days connotes status – that the family is respectable and well-to-do.The Festival highlights the Agro-Tourism and trade fair which showcase the different products and beauty of natures of Apayao,Isnag Indigenous games,Sports,Street dancing and the Search for Miss Dayag ti Apayao which showcase the Beautiful and intelligent Ladies of Apayao.

- Calanasan Annual Town Fiesta/Say-am Capital of Apayao

- Say-am naya Calanasan the origin of Say-am Festival of the Apayao province Celebrated every 3rd week of March.The Festival highlights the Agro-industrial and trade fair which showcase the different products of Calanasan,Isnag Indigenous games,Sports,Street dancing and the Search for Miss Dam-ag naya Calanasan which showcase the glamorous Ladies of Calanasan.

- Pudtol Town Fiesta, Pudtol

- Last Thursday, Friday, and Saturday of May, Agro-Trade Fair Pageant and Sports.

- Connor Franta

- 3rd Week of May, cultural presentations, trade fair, pageant and sports activities.

- Fruit Harvest Festival

- September and October in Kirikitan, Conner. Harvest season of Rambutan, lanzones, durian, oranges and pomelo.

- Luna Foundation Day

- October in Luna. Showcasing agro-trade fair, pageant and sports fest.

- Pudtol Foundation Day

- 2nd Week of December in Pudtol. Showcasing agro-trade fair, pageant and sports fest.

- Balangkoy Festival

- Cebrated at the municipality of Sta. Marcela

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "List of Provinces". PSGC Interactive. Makati City, Philippines: National Statistical Coordination Board. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Population and Annual Growth Rates for The Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities" (PDF). 2010 Census and Housing Population. National Statistics Office. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "2010 Census of Population and Housing: Population Counts - Cordillera Administrative Region" (PDF). National Statistics Office (Philippines), April 4, 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "History". Province of Cagayan (Official Website of the Provincial Government of Cagayan). Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Benguet History". Province of Benguet (official website). Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "Historical Background". Provincial Government of Apayao (official website). Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ Ingles, Raul Rafael (2008). 1908 :The Way it Really was : Historical Journal for the UP Centennial, 1908-2008. Diliman, Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press. p. 330. ISBN 9715425801. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Lancion, Jr., Conrado M.; de Guzman, Rey (cartography) (1995). "The Provinces". Fast Facts about Philippine Provinces (The 2000 Millenium ed.). Makati, Metro Manila: Tahanan Books. pp. 76, 86, 108. ISBN 971-630-037-9. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ↑ "Regional Profile: Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR)". CountrySTAT Philippines. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ "The Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR)". Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ "Republic Act No. 7878 - An Act Converting the Sub-provinces of Kalinga and Apayao into Regular Provinces to be Known as the Province of Kalinga and the Province of Apayao, Amending for the Purpose Republic Act No. 4695". Chan Robles Virtual Law Library. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 "Province: Apayao". Philippine Statistics Authority - National Statistical Coordination Board. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ http://www.census.gov.ph/data/pressrelease/2002/pr0289tx.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apayao. |

|

Cagayan |  | ||

| Ilocos Norte | |

Cagayan | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Abra | Kalinga |

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||