Antvorskov

Antvorskov was the principal Scandinavian monastery of the Roman Catholic Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, located about one kilometer south of the town of Slagelse on Zealand, Denmark.

It served as the Scandinavian headquarters of the Order, known also as "the Hospitallers", and the prior of Antvorskov reported directly to the great officer of the Order in Germany, the Grand Master of the Order on Rhodes (and, later, on Malta), and the pope. As a result, Antvorskov was one of the most important monastic houses in Denmark. Before the Reformation, its prior often served as a member of the Council of State (Danish:rigsråd) as well.

History

In 1165, Valdemar the Great, who was himself an honorary Knight of St John, gave the Order land at Antvorskov. The monastery (Danish:kloster) was constructed soon thereafter, during the time of Archbishop Eskil. The mother monastery, on Rhodes, and a monastery on Cyprus were built to house pilgrims to the Holy Land. Daughter houses such as Antvorskov were to forward any profits from properties to the monastery on Rhodes. Over time, however, especially after the collapse of Crusader kingdoms in Palestine, the Order focused more on helping local people, especially those suffering from leprosy, which was not uncommon in mediaeval Europe.[1]

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the monastery became one of Denmark's major landowners. Many persons nearing death and seeking to withdraw from the world into a quasi-religious life donated some or all of their goods to the monastery. Many families seeking heavenly rest for their kinsmen donated property to buy prayers in perpetuity for those deceased relatives, or to buy burial places inside the abbey church.

Despite the vast landholdings attached to the monastery, the central government of the Order on Rhodes (and, later, on Malta) often scolded Antvorskov for failing to send the required excess to the mother house. In time, Antvorskov came to own farms and land all over Denmark and as far south as Rűgen, where a daughter abbey at Maschenholt was established in 1435.

Notable residents

The list of priors is long, but a few outstandingly notable names appear. Henrik of Hohenscheid was an advisor to the Danish kings Erik V and Erik VI, from whom the monastery received many lucrative holdings. Jep Mortensen rebuilt the monastery between 1468 and 1490, and he added a new chapel attached to the abbey church. Eskil Thomesen, the last Roman Catholic prior, received permission to wear the vestments of a bishop and perform a bishop's functions without being ordained. Thomesen opposed the introduction of Lutheran teaching and was responsible for sending Hans Tausen, who lived at the monastery, to prison in Viborg for teaching Lutheran "heresy" in the Good Friday sermon in 1525 that sparked the Reformation in Denmark. Thomesen refused to ratify the election in 1534 of Christian III, whom he fiercely opposed, to the Danish throne. When Count Christopher of Oldenburg failed to achieve the reinstatement of Christian II as king, Christian III persecuted both Thomesen and the monastic institution. The king demanded money from the monastery to pay off the debt he had incurred in securing his election to the throne.[1]

Other residents

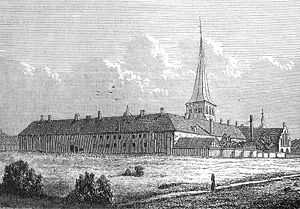

After the Reformation, the monastery complex became a royal residence. In 1585, it became illegal to use the name "Antvorskov Abbey" to refer to the property; it was thenceforth to be called "Antvorskov Castle" (Danish: Antvorskov Slot).[2] Frederik II died at Antvorskov in 1588. Frederik IV's wife was created Countess of Antvorskov, but upon her death the properties reverted to the crown. In 1717, the castle became for a while a staging location for the Danish army, housing troops.

The abbey church was reopened for services in 1722, but the new owner, Finance Minister Koes, ordered the church to be pulled down and the materials used to rebuild his manor at Falkenstein. In 1774, lands at Anvorskov were broken into nine large estates, which passed into the hands of local noble families. In 1799, State Minister Bruun bought the remaining estate, divided it into four parcels, and sold them off.

The remnants of the monastic complex crumbled, visited by Danes and others as a picturesque reminder of the distant past; in his autobiography, Hans Christian Andersen, for example, mentions excursions to the ruins of the monastery. But by 1816, the last of the ancient buildings stood in hopeless disrepair and were torn down.