Antonio Gramsci

| Antonio Gramsci | |

|---|---|

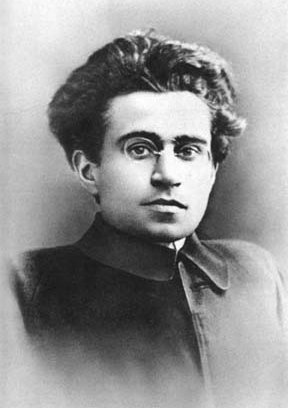

Gramsci in 1916 | |

| Born |

22 January 1891 Ales, Sardinia (Kingdom of Italy) |

| Died |

27 April 1937 (aged 46) Rome |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Marxism |

Main interests | Politics, ideology, culture |

Notable ideas | Hegemony, war of position, the distinction between "traditional" and "organic" intellectuals |

Antonio Gramsci (![]() /anˈtɔːnjo ˈɡramʃi/ ; 22 January 1891 – 27 April 1937) was an Italian Marxist theoretician and politician. He wrote on political theory, sociology and linguistics. He was a founding member and one-time leader of the Communist Party of Italy and was imprisoned by Benito Mussolini's Fascist regime. Gramsci is best known for his theory of cultural hegemony, which describes how states use cultural institutions to maintain power in capitalist societies.

/anˈtɔːnjo ˈɡramʃi/ ; 22 January 1891 – 27 April 1937) was an Italian Marxist theoretician and politician. He wrote on political theory, sociology and linguistics. He was a founding member and one-time leader of the Communist Party of Italy and was imprisoned by Benito Mussolini's Fascist regime. Gramsci is best known for his theory of cultural hegemony, which describes how states use cultural institutions to maintain power in capitalist societies.

Life

Early life

Gramsci was born in Ales, on the island of Sardinia, the fourth of seven sons of Francesco Gramsci (1860–1937). The senior Gramsci was a low-level official from Gaeta, who married Giuseppina Marcias (1861–1932). Gramsci's father was of Arbëreshë descent,[1] while his mother belonged to a local landowning family. The senior Gramsci's financial difficulties and troubles with the police forced the family to move about through several villages in Sardinia until they finally settled in Ghilarza.[2]

In 1898 Francesco was convicted of embezzlement and imprisoned, reducing his family to destitution. The young Antonio had to abandon schooling and work at various casual jobs until his father's release in 1904.[3] As a boy, Gramsci suffered from health problems, particularly a malformation of the spine that stunted his growth (his adult height was less than 5 feet)[4] and left him seriously hunchbacked. For decades, it was reported that his condition had been due to a childhood accident – specifically, having been dropped by a nanny – but more recently it has been suggested that it was due to Pott disease,[5] a form of tuberculosis that can cause deformity of the spine. Gramsci was also plagued by various internal disorders throughout his life.

Gramsci completed secondary school in Cagliari, where he lodged with his elder brother Gennaro, a former soldier whose time on the mainland had made him a militant socialist. However, Gramsci's sympathies then did not lie with socialism, but rather with the grievances of impoverished Sardinian peasants and miners.[6] They perceived their neglect as a result of privileges enjoyed by the rapidly industrialising North, and they tended to turn to Sardinian nationalism as a response.

Turin

In 1911, Gramsci won a scholarship to study at the University of Turin, sitting the exam at the same time as Palmiro Togliatti.[7] At Turin, he read literature and took a keen interest in linguistics, which he studied under Matteo Bartoli. Gramsci was in Turin as it was going through industrialization, with the Fiat and Lancia factories recruiting workers from poorer regions. Trade unions became established, and the first industrial social conflicts started to emerge.[8] Gramsci frequented socialist circles as well as associating with Sardinian emigrants. His worldview was shaped by both his earlier experiences in Sardinia and his environment on the mainland. Gramsci joined the Italian Socialist Party in late 1913.

Despite showing talent for his studies, Gramsci had financial problems and poor health. Together with his growing political commitment, these led to his abandoning his education in early 1915. By this time, he had acquired an extensive knowledge of history and philosophy. At university, he had come into contact with the thought of Antonio Labriola, Rodolfo Mondolfo, Giovanni Gentile and, most importantly, Benedetto Croce, possibly the most widely respected Italian intellectual of his day. Such thinkers espoused a brand of Hegelian Marxism to which Labriola had given the name "philosophy of praxis".[9] Though Gramsci would later use this phrase to escape the prison censors, his relationship with this current of thought was ambiguous throughout his life.

From 1914 onward, Gramsci's writings for socialist newspapers such as Il Grido del Popolo earned him a reputation as a notable journalist. In 1916 he became co-editor of the Piedmont edition of Avanti!, the Socialist Party official organ. An articulate and prolific writer of political theory, Gramsci proved a formidable commentator, writing on all aspects of Turin's social and political life.[10]

Gramsci was, at this time, also involved in the education and organisation of Turin workers: he spoke in public for the first time in 1916 and gave talks on topics such as Romain Rolland, the French Revolution, the Paris Commune and the emancipation of women. In the wake of the arrest of Socialist Party leaders that followed the revolutionary riots of August 1917, Gramsci became one of Turin's leading socialists when he was both elected to the party's Provisional Committee and made editor of Il Grido del Popolo.[11]

In April 1919 with Togliatti, Angelo Tasca and Umberto Terracini Gramsci set up the weekly newspaper L'Ordine Nuovo (The New Order). In October of the same year, despite being divided into various hostile factions, the Socialist Party moved by a large majority to join the Third International. The L'Ordine Nuovo group was seen by Vladimir Lenin as closest in orientation to the Bolsheviks, and it received his backing against the anti-parliamentary programme of the extreme left Amadeo Bordiga.

Amongst the various tactical debates that took place within the party, Gramsci's group was mainly distinguished by its advocacy of workers' councils, which had come into existence in Turin spontaneously during the large strikes of 1919 and 1920. For Gramsci these councils were the proper means of enabling workers to take control of the task of organising production. Although he believed his position at this time to be in keeping with Lenin's policy of "All power to the Soviets", his stance was attacked by Bordiga for betraying a syndicalist tendency influenced by the thought of Georges Sorel and Daniel DeLeon. By the time of the defeat of the Turin workers in spring 1920, Gramsci was almost alone in his defence of the councils.

In the Communist Party of Italy

The failure of the workers' councils to develop into a national movement led Gramsci to believe that a Communist Party in the Leninist sense was needed. The group around L'Ordine Nuovo declaimed incessantly against the Italian Socialist Party's centrist leadership and ultimately allied with Bordiga's far larger "abstentionist" faction. On 21 January 1921, in the town of Livorno (Leghorn), the Communist Party of Italy (Partito Comunista d'Italia – PCI) was founded. Gramsci supported against Bordiga the Arditi del Popolo, a militant anti-fascist group which struggled against the Blackshirts.

Gramsci would be a leader of the party from its inception but was subordinate to Bordiga, whose emphasis on discipline, centralism and purity of principles dominated the party's programme until the latter lost the leadership in 1924.

In 1922 Gramsci travelled to Russia as a representative of the new party. Here, he met Julia Schucht, a young violinist whom Gramsci married in 1923 and by whom he had two sons, Delio (born 1924) and Giuliano (born 1926).[12] Gramsci never saw his second son.[13]

The Russian mission coincided with the advent of Fascism in Italy, and Gramsci returned with instructions to foster, against the wishes of the PCI leadership, a united front of leftist parties against fascism. Such a front would ideally have had the PCI at its centre, through which Moscow would have controlled all the leftist forces, but others disputed this potential supremacy: socialists did have a certain tradition in Italy too, while the communist party seemed relatively young and too radical. Many believed that an eventual coalition led by communists would have functioned too remotely from political debate, and thus would have run the risk of isolation.

In late 1922 and early 1923, Benito Mussolini's government embarked on a campaign of repression against the opposition parties, arresting most of the PCI leadership, including Bordiga. At the end of 1923, Gramsci travelled from Moscow to Vienna, where he tried to revive a party torn by factional strife.

In 1924 Gramsci, now recognised as head of the PCI, gained election as a deputy for the Veneto. He started organizing the launch of the official newspaper of the party, called L'Unità (Unity), living in Rome while his family stayed in Moscow. At its Lyon Congress in January 1926, Gramsci's theses calling for a united front to restore democracy to Italy were adopted by the party.

In 1926 Joseph Stalin's manoeuvres inside the Bolshevik party moved Gramsci to write a letter to the Comintern, in which he deplored the opposition led by Leon Trotsky, but also underlined some presumed faults of the leader. Togliatti, in Moscow as a representative of the party, received the letter, opened it, read it, and decided not to deliver it. This caused a difficult conflict between Gramsci and Togliatti which they never completely resolved.[14]

Imprisonment and death

On 9 November 1926 the Fascist government enacted a new wave of emergency laws, taking as a pretext an alleged attempt on Mussolini's life several days earlier. The fascist police arrested Gramsci, despite his parliamentary immunity, and brought him to the Roman prison Regina Coeli.

At his trial, Gramsci's prosecutor stated, "For twenty years we must stop this brain from functioning".[15] He received an immediate sentence of 5 years in confinement on the island of Ustica and the following year he received a sentence of 20 years of prison in Turi, near Bari. In prison his health deteriorated. In 1932, a project for exchanging political prisoners (including Gramsci) between Italy and the Soviet Union failed. In 1934 he gained conditional freedom on health grounds, after visiting hospitals in Civitavecchia, Formia and Rome. He died in 1937, at the "Quisisana" Hospital in Rome at the age of 46. His ashes are buried in the Protestant Cemetery there.

In an interview archbishop Luigi de Magistris, former head of the Apostolic Penitentiary of the Holy See stated that during Gramsci's final illness, he "returned to the faith of his infancy" and "died taking the sacraments."[16] However, Italian State documents on his death show that no religious official was sent for or received by Gramsci. Other witness accounts of his death also do not mention any conversion to Catholicism or recantation by Gramsci of his atheism.[17] Cremation, which was banned for Catholics, and his ashes being buried in a Protestant cemetery, would both be further evidence that he had no deathbed conversion.

Thought

Gramsci was one of the most important Marxist thinkers of the twentieth century, and a particularly key thinker in the development of Western Marxism. He wrote more than 30 notebooks and 3000 pages of history and analysis during his imprisonment. These writings, known as the Prison Notebooks, contain Gramsci's tracing of Italian history and nationalism, as well as some ideas in Marxist theory, critical theory and educational theory associated with his name, such as:

- Cultural hegemony as a means of maintaining and legitimising the capitalist state.

- The need for popular workers' education to encourage development of intellectuals from the working class.

- An analysis of the modern capitalist state that distinguishes between political society, which dominates directly and coercively, and civil society, where leadership is constituted by means of consent.

- "Absolute historicism".

- A critique of economic determinism that opposes fatalistic interpretations of Marxism.

- A critique of philosophical materialism.

Hegemony

Hegemony was a term previously used by Marxists such as Vladimir Ilyich Lenin to denote the political leadership of the working-class in a democratic revolution.[18] Gramsci greatly expanded this concept, developing an acute analysis of how the ruling capitalist class – the bourgeoisie – establishes and maintains its control.[19]

Orthodox Marxism had predicted that socialist revolution was inevitable in capitalist societies. By the early 20th century, no such revolution had occurred in the most advanced nations. Capitalism, it seemed, was even more entrenched than ever. Capitalism, Gramsci suggested, maintained control not just through violence and political and economic coercion, but also through ideology. The bourgeoisie developed a hegemonic culture, which propagated its own values and norms so that they became the "common sense" values of all. People in the working-class (and other classes) identified their own good with the good of the bourgeoisie, and helped to maintain the status quo rather than revolting.

To counter the notion that bourgeois values represented "natural" or "normal" values for society, the working class needed to develop a culture of its own. Lenin held that culture was "ancillary" to political objectives, but for Gramsci it was fundamental to the attainment of power that cultural hegemony be achieved first. In Gramsci's view, a class cannot dominate in modern conditions by merely advancing its own narrow economic interests. Neither can it dominate purely through force and coercion. Rather, it must exert intellectual and moral leadership, and make alliances and compromises with a variety of forces. Gramsci calls this union of social forces a "historic bloc", taking a term from Georges Sorel. This bloc forms the basis of consent to a certain social order, which produces and re-produces the hegemony of the dominant class through a nexus of institutions, social relations, and ideas. In this manner, Gramsci developed a theory that emphasized the importance of the political and ideological superstructure in both maintaining and fracturing relations of the economic base.

Gramsci stated that bourgeois cultural values were tied to folklore, popular culture and religion, and therefore much of his analysis of hegemonic culture is aimed at these. He was also impressed by the influence Roman Catholicism had and the care the Church had taken to prevent an excessive gap developing between the religion of the learned and that of the less educated. Gramsci saw Marxism as a marriage of the purely intellectual critique of religion found in Renaissance humanism and the elements of the Reformation that had appealed to the masses. For Gramsci, Marxism could supersede religion only if it met people's spiritual needs, and to do so people would have to think of it as an expression of their own experience.

For Gramsci, hegemonic dominance ultimately relied on a "consented" coercion, and in a "crisis of authority" the "masks of consent" slip away, revealing the fist of force.

Intellectuals and education

Gramsci gave much thought to the role of intellectuals in society. Famously, he stated that all men are intellectuals, in that all have intellectual and rational faculties, but not all men have the social function of intellectuals.[20] He saw modern intellectuals not as talkers, but as practically-minded directors and organisers who produced hegemony through ideological apparatuses such as education and the media. Furthermore, he distinguished between a "traditional" intelligentsia which sees itself (wrongly) as a class apart from society, and the thinking groups which every class produces from its own ranks "organically". Such "organic" intellectuals do not simply describe social life in accordance with scientific rules, but instead articulate, through the language of culture, the feelings and experiences which the masses could not express for themselves. The need to create a working-class culture relates to Gramsci's call for a kind of education that could develop working-class intellectuals, whose task was not to introduce Marxist ideology from without the proletariat, but to renovate and make critical of the status quo the already existing intellectual activity of the masses. His ideas about an education system for this purpose correspond with the notion of critical pedagogy and popular education as theorized and practised in later decades by Paulo Freire in Brazil, and have much in common with the thought of Frantz Fanon. For this reason, partisans of adult and popular education consider Gramsci an important voice to this day.

State and civil society

Gramsci's theory of hegemony is tied to his conception of the capitalist state. Gramsci does not understand the 'state' in the narrow sense of the government. Instead, he divides it between 'political society' (the police, the army, legal system, etc.) – the arena of political institutions and legal constitutional control – and 'civil society' (the family, the education system, trade unions, etc.) – commonly seen as the 'private' or 'non-state' sphere, mediating between the state and the economy. He stresses, however, that the division is purely conceptual and that the two, in reality, often overlap.[21] The capitalist state, Gramsci claims, rules through force plus consent: political society is the realm of force and civil society is the realm of consent.

Gramsci proffers that under modern capitalism, the bourgeoisie can maintain its economic control by allowing certain demands made by trade unions and mass political parties within civil society to be met by the political sphere. Thus, the bourgeoisie engages in passive revolution by going beyond its immediate economic interests and allowing the forms of its hegemony to change. Gramsci posits that movements such as reformism and fascism, as well as the 'scientific management' and assembly line methods of Frederick Taylor and Henry Ford respectively, are examples of this.

Drawing from Machiavelli, he argues that 'The Modern Prince' – the revolutionary party – is the force that will allow the working-class to develop organic intellectuals and an alternative hegemony within civil society. For Gramsci, the complex nature of modern civil society means that a 'war of position', carried out by revolutionaries through political agitation, the trade unions, advancement of proletarian culture, and other ways to create an opposing civil society was necessary alongside a 'war of maneuver' – a direct revolution – in order to have a successful revolution without a danger of a counter-revolution or degeneration.

Despite his claim that the lines between the two may be blurred, Gramsci rejects the state-worship that results from identifying political society with civil society, as was done by the Jacobins and Fascists. He believes the proletariat's historical task is to create a 'regulated society' and defines the 'withering away of the state' as the full development of civil society's ability to regulate itself.

Historicism

Gramsci, like the early Marx, was an emphatic proponent of historicism.[22] In Gramsci's view, all meaning derives from the relation between human practical activity (or "praxis") and the "objective" historical and social processes of which it is a part. Ideas cannot be understood outside their social and historical context, apart from their function and origin. The concepts by which we organise our knowledge of the world do not derive primarily from our relation to things (to an objective reality), but rather from the social (economic, for Marx) relations between the bearers of those concepts. As a result, there is no such thing as an unchanging "human nature". Furthermore, philosophy and science do not "reflect" a reality independent of man. Rather, a theory can be said to be "true" when, in any given historical situation, it expresses the real developmental trend of that situation.

For the majority of Marxists, truth was truth no matter when and where it is known, and scientific knowledge (which included Marxism) accumulated historically as the advance of truth in this everyday sense. On this view, Marxism (or the Marxist theory of history and economics) could not be said to not belong to the (largely) illusory realm of the superstructure because it is a science. In contrast, Gramsci believed Marxism was "true" in a socially pragmatic sense: by articulating the class consciousness of the proletariat, Marxism expressed the "truth" of its times better than any other theory. This anti-scientistic and anti-positivist stance was indebted to the influence of Benedetto Croce. However, it should be underlined that Gramsci's "absolute historicism" broke with Croce's tendency to secure a metaphysical synthesis in historical "destiny". Though Gramsci repudiates the charge, his historical account of truth has been criticised as a form of relativism.

Critique of "economism"

In a notable pre-prison article entitled "The Revolution against Das Kapital", Gramsci claimed that the October Revolution in Russia had invalidated the idea that socialist revolution had to await the full development of capitalist forces of production. This reflected his view that Marxism was not a determinist philosophy. The principle of the causal "primacy" of the forces of production, he held, was a misconception of Marxism. Both economic changes and cultural changes are expressions of a "basic historical process", and it is difficult to say which sphere has primacy over the other. The belief, widespread within the workers' movement in its earliest years, that it would inevitably triumph due to "historical laws", was, in Gramsci's view, a product of the historical circumstances of an oppressed class restricted mainly to defensive action. Such a fatalistic doctrine was to be abandoned as a hindrance once the working-class became able to take the initiative. Because Marxism is a "philosophy of praxis", it cannot rely on unseen "historical laws" as the agents of social change. History is defined by human praxis and therefore includes human will. Nonetheless, will-power cannot achieve anything it likes in any given situation: when the consciousness of the working-class reaches the stage of development necessary for action, it will encounter historical circumstances that cannot be arbitrarily altered. However, it is not predetermined by historical inevitability or "destiny" as to which of several possible developments will take place as a result.

His critique of economism also extended to that practiced by the syndicalists of the Italian trade unions. He believed that many trade unionists had settled for a reformist, gradualist approach in that they had refused to struggle on the political front in addition to the economic front. For Gramsci, much as the ruling class can look beyond its own immediate economic interests to reorganise the forms of its own hegemony, so must the working-class present its own interests as congruous with the universal advancement of society. While Gramsci envisioned the trade unions as one organ of a counter-hegemonic force in capitalist society, the trade union leaders simply saw these organizations as a means to improve conditions within the existing structure. Gramsci referred to the views of these trade unionists as "vulgar economism", which he equated to covert reformism and even liberalism.

Critique of materialism

By virtue of his belief that human history and collective praxis determine whether any philosophical question is meaningful or not, Gramsci's views run contrary to the metaphysical materialism and 'copy' theory of perception advanced by Engels[23][24] and Lenin,[25] though he does not explicitly state this. For Gramsci, Marxism does not deal with a reality that exists in and for itself, independent of humanity.[26] The concept of an objective universe outside of human history and human praxis was, in his view, analogous to belief in God.[27] Gramsci defined objectivity in terms of a universal intersubjectivity to be established in a future communist society.[27] Natural history was thus only meaningful in relation to human history. In his view philosophical materialism resulted from a lack of critical thought,[28] and could not be said to oppose religious dogma and superstition.[29] Despite this, Gramsci resigned himself to the existence of this arguably cruder form of Marxism. Marxism was a philosophy for the proletariat, a subaltern class, and thus could often only be expressed in the form of popular superstition and common sense.[30] Nonetheless, it was necessary to effectively challenge the ideologies of the educated classes, and to do so Marxists must present their philosophy in a more sophisticated guise, and attempt to genuinely understand their opponents’ views.

Influence

Gramsci's thought emanates from the organized left, but he has also become an important figure in current academic discussions within cultural studies and critical theory. Political theorists from the center and the right have also found insight in his concepts; his idea of hegemony, for example, has become widely cited. His influence is particularly strong in contemporary political science (see Neo-gramscianism). His work also heavily influenced intellectual discourse on popular culture and scholarly popular culture studies in whom many have found the potential for political or ideological resistance to dominant government and business interests.

His critics charge him with fostering a notion of power struggle through ideas. They find the Gramscian approach to philosophical analysis, reflected in current academic controversies, to be in conflict with open-ended, liberal inquiry grounded in apolitical readings of the classics of Western culture. Gramscians would counter that thoughts of "liberal inquiry" and "apolitical reading" are utterly naive; for the Gramscians, these are intellectual devices used to maintain the hegemony of the capitalist class. To credit or blame Gramsci for the travails of current academic politics is an odd turn of history, since Gramsci himself was never an academic, and was in fact deeply intellectually engaged with Italian culture, history, and current liberal thought.

As a socialist, Gramsci's legacy has been disputed.[31] Togliatti, who led the Party (renamed as Italian Communist Party, PCI) after World War II and whose gradualist approach was a forerunner to Eurocommunism, claimed that the PCI's practices during this period were congruent with Gramscian thought. Others, however, have argued that Gramsci was a Left Communist, who would likely have been expelled from his Party if prison had not prevented him from regular contact with Moscow during the leadership of Joseph Stalin.

In culture

Occupations – Gramsci is a central character in Trevor Griffiths's 1970 play Occupations about workers taking over car factories in Turin in 1920.

A major road going through the lower portion of Genoa, along the coast, is named after Antonio Gramsci.

Bibliography

- Pre-Prison Writings (Cambridge University Press)

- The Prison Notebooks (three volumes) (Columbia University Press)

- Selections from the Prison Notebooks (International Publishers)

See also

- Category:Italian anarchists

- Cultural hegemony

- Subaltern Studies

- Reformism

- Articulation

- Risorgimento

- Praxis School

- Liberation theology

- Antonio Gramsci Battalion

References

- ↑ Dante L. Germino, Antonio Gramsci: Architect of a New Politics, Louisiana Press University, 1990 ISBN 0-8071-1553-3 page 157

- ↑ Hoare, Quentin & Smith, Geoffrey Nowell, (1971). "Introduction". In Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, pp. xvii–xcvi. New York: International Publishers, p. xviii.

- ↑ Hoare, Quentin & Smith, Geoffrey Nowell, (1971). "Introduction". In Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, pp. xvii–xcvi. New York: International Publishers, p. xviii–xix.

- ↑ Crehan, Kate. Gramsci, Culture, and Anthropology. University of California Press. 2002. page 14.

- ↑ Daniel M. Markowicz, "Gramsci, Antonio," The Encyclopedia of Literary and Cultural Theory, Edited by: Michael Ryan, eISBN 9781405183123, Print publication date: 2011

- ↑ Hoare, Quentin & Smith, Geoffrey Nowell, (1971). "Introduction". In Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, pp. xvii–xcvi. New York: International Publishers, p. xix.

- ↑ Hoare, Quentin & Smith, Geoffrey Nowell, (1971). "Introduction". In Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, pp. xvii–xcvi. New York: International Publishers, p. xx.

- ↑ Hoare, Quentin & Smith, Geoffrey Nowell, (1971). "Introduction". In Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, pp. xvii–xcvi. New York: International Publishers, p. xxv.

- ↑ Hoare, Quentin & Smith, Geoffrey Nowell, (1971). "Introduction". In Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, pp. xvii–xcvi. New York: International Publishers, p. xxi.

- ↑ Hoare, Quentin & Smith, Geoffrey Nowell, (1971). "Introduction". In Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, pp. xvii–xcvi. New York: International Publishers, p. xxx.

- ↑ Hoare, Quentin & Smith, Geoffrey Nowell, (1971). "Introduction". In Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, pp. xvii–xcvi. New York: International Publishers, p. xxx–xxxi.

- ↑ Picture of Gramsci's wife and their two sons at the Italian-language Antonio Gramsci Website.

- ↑ Crehan, Kate. Gramsci, Culture, and Anthropology. University of California Press. 2002. page 17.

- ↑ Giuseppe Vacca.Vita e Pensieri Di Antonio Gramsci.Einaudi.Torino 2012

- ↑ Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, Lawrence and Wishart, 1971, ISBN 0-85315-280-2, p.lxxxix.

- ↑ Owen, Richard (25 November 2008). "The founder of Italian Communism had deathbed conversion". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ↑ Allen Jr., John L. (25 November 2008). "Founder of Italian Communism died a good Catholic, Vatican prelate says". National Catholic Reporter Conversation Cafe. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ↑ Perry Anderson, 1976. The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci. New Left Review., p. 15-17.

- ↑ Perry Anderson, 1976. The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci. New Left Review., p. 20.

- ↑ Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Books, p.9. Lawrence and Wishart: 1982. ISBN 0-85315-280-2.

- ↑ Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Books, p.160. International Publishers: 1992. ISBN 0-7178-0397-X.

- ↑ Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Books, p.404-407. Lawrence and Wishart: 1982. ISBN 0-85315-280-2.

- ↑ Friedrich Engels: Anti-Duehring

- ↑ Friedrich Engels: Dialectics of Nature

- ↑ Lenin: Materialism and Empirio-Criticism.

- ↑ Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Books, p.440-448. Lawrence and Wishart: 1982. ISBN 0-85315-280-2.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Books, p.445. Lawrence and Wishart: 1982. ISBN 0-85315-280-2.

- ↑ Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Books, p.444-445. Lawrence and Wishart: 1982. ISBN 0-85315-280-2.

- ↑ Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Books, p.420. Lawrence and Wishart: 1982. ISBN 0-85315-280-2.

- ↑ Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Books, p.419-425. Lawrence and Wishart: 1982. ISBN 0-85315-280-2.

- ↑ Perry Anderson, 1976. The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci. New Left Review., p. 6-7.

Further reading

- Anderson, Perry (1976). The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci. London: New Left Review.

- Boggs, Carl (1984). The Two Revolutions: Gramsci and the Dilemmas of Western Marxism. London: South End Press. ISBN 0-89608-226-1.

- Bottomore, Tom (1992). The Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-18082-6.

- Gramsci, Antonio (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0397-X.

- Harman Chris Gramsci, the Prison Notebooks and Philosophy

- Jay, Martin (1986). Marxism and Totality: The Adventures of a Concept from Lukacs to Habermas. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05742-2.

- Joll, James (1977). Antonio Gramsci. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-12942-9.

- Kolakowski, Leszek (1981). Main Currents of Marxism, Vol. III: The Breakdown. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-285109-8.

- Maitan, Livio (1978). Il marxismo rivoluzionario di Antonio Gramsci. Milano: Nuove edizioni internazionali.

- Pastore, Gerardo (2011), Antonio Gramsci. Questione sociale e questione sociologica. Livorno: Belforte. ISBN 978-88-7467-059-8.

- Santucci, Antonio A. (2010). Antonio Gramsci. Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-210-5.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Antonio Gramsci |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Antonio Gramsci. |

- Gramsci's writings at MIA

- The International Gramsci Society

- "Notes on Language". TELOS

- Fondazione Instituto Gramsci

- Special issue of International Socialism journal with a collection on Gramsci's legacy

- Roberto Robaina: Gramsci and revolution: a necessary clarification

- Dan Jakopovich: Revolution and the Party in Gramsci's Thought: A Modern Application

- Gramsci's contribution to the field of adult and popular education

- The life and work of Antonio Gramsci

- (Italian) Antonio Gramsci, 1891–1937

- The Whole Picture – Gramscian Epistemology through the Praxis Prism

- Gramsci Links Archive

- Bob Jessop's lectures on Gramsci

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|