Antisymmetry

In linguistics, antisymmetry is a theory of syntactic linearization presented in Richard Kayne's 1994 monograph The Antisymmetry of Syntax.[1] The crux of this theory is that hierarchical structure in natural language maps universally onto a particular surface linearization, namely specifier-head-complement branching order. The theory derives a version of X-bar theory. Kayne hypothesizes that all phrases whose surface order is not specifier-head-complement have undergone movements that disrupt this underlying order. Subsequently, there have also been attempts at deriving specifier-complement-head as the basic word order.[2]

Antisymmetry as a principle of word order is reliant on assumptions that many theories of syntax dispute, e.g. constituency structure (as opposed to dependency structure), X-bar notions such as specifier and complement, and the existence of ordering altering mechanisms such as movement and/or copying.

Asymmetric c-command

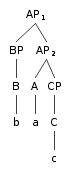

The theory is based on a notion of asymmetric c-command, c-command being a relation between nodes in a tree originally defined by Tanya Reinhart. Kayne uses a simple definition of c-command based on the "first node up". However, the definition is complicated by his use of a "segment/category distinction". A category is a kind of extended node; if two directly connected nodes in a tree have the same label, these two nodes are both segments of a single category. C-command is defined in terms of categories using the notion of "exclusion". A category excludes all categories not dominated by both its segments. A c-commands B if every category that dominates A also dominates B, and A excludes B. The following tree illustrates these concepts:

AP1 and AP2 are both segments of a single category. AP does not c-command BP because it does not exclude BP. CP does not c-command BP because both segments of AP do not dominate BP (so it is not the case that every category that dominates CP dominates BP). BP c-commands CP and A. A c-commands C. The definitions above may perhaps be thought to allow BP to c-command AP, but a c-command relation is not usually assumed to hold between two such categories, and for the purposes of antisymmetry, the question of whether BP c-commands AP is in fact moot.

(The above is not an exhaustive list of c-command relations in the tree, but covers all of those that are significant in the following exposition.)

Asymmetric c-command is the relation that holds between two categories, A and B, if A c-commands B but B does not c-command A. This relationship is a primitive in Kayne's theory of linearization, the process that converts a tree structure into a flat (structureless) string of terminal nodes.

Precedence and asymmetric c-command

Informally, Kayne's theory states that if a nonterminal category A c-commands another nonterminal category B, all the terminal nodes dominated by A must precede all of the terminal nodes dominated by B (this statement is commonly referred to as the "Linear Correspondence Axiom" or LCA). Moreover, this principle must suffice to establish a complete and consistent ordering of all terminal nodes — if it cannot consistently order all of the terminal nodes in a tree, the tree is illicit. Consider the following tree:

(S and S' may either be simplex structures like BP, or complex structures with specifiers and complements like CP.)

In this tree, the set of pairs of nonterminal categories such that the first member of the pair asymmetrically c-commands the second member is as follows: {<BP, A>, <BP, CP>, <A, CP>}. This gives rise to the total ordering: <b, a, c>.

As a result, there is no right adjunction, and hence in practice no rightward movement either.[3] Furthermore, the underlying order must be specifier-head-complement.

Derivation of X-bar theory

The example tree in the first section of this article is in accordance with X-bar theory (with the exception that [Spec,CP] is treated as an adjunct). It can be seen that removing any of the structure in the tree (e.g. deleting the C dominating the 'c' terminal, so that the complement of A is [CP c]) will destroy the asymmetric c-command relations necessary for linearly ordering the terminals of the tree.

The universal order

Kayne notes that his theory permits either a universal specifier-head-complement order or a universal complement-head-specifier order, depending on whether asymmetric c-command establishes precedence or subsequence (S-H-C results from precedence) (pp. 35–36)[1] He argues that there are good empirical grounds for preferring S-H-C as the universal underlying order, since the typologically most widely attested order is for specifiers to precede heads and complements (though the order of heads and complements themselves is relatively free). He further argues that a movement approach to deriving non S-H-C orders is appropriate, since it derives asymmetries in typology (such as the fact that "verb second" languages such as German are not mirrored by any known "verb second-from-last" languages).

Derived orders: the case of Japanese wh-questions

Perhaps the biggest challenge for antisymmetry is to explain the wide variety of different surface orders across languages. Any deviation from Spec-Head-Comp order (which implies overall Subject-Verb-Object order, if objects are complements) must be explained by movement. Kayne argues that in some cases, the need for extra movements (previously unnecessary because different underlying orders were assumed for different languages) can actually explain some mysterious typological generalizations. His explanation for the lack of wh-movement in Japanese is the most striking example of this. From the mid-1980s onwards, the standard analysis of wh-movement involved the wh-phrase moving leftward to a position on the left edge of the clause called [Spec,CP] (i.e., the specifier of the CP phrase). Thus, a derivation of the English question What did John buy? would proceed roughly as follows:

- [CP {Spec,CP position} John did buy what]

- wh-movement →

- [CP What did John buy]

The Japanese equivalent of this sentence is as follows[4] (note the lack of wh-movement):

| John-wa | nani-o | kaimasita | ka |

| John-topic_marker | what-accusative | bought | question_particle |

Japanese has an overt "question particle" (ka), which appears at the end of the sentence in questions. It is generally assumed that languages such as English have a "covert" (i.e. phonologically null) equivalent of this particle in the 'C' position of the clause — the position just to the right of [Spec,CP]. This particle is overtly realised in English by movement of an auxiliary to C (in the case of the example above, by movement of did to C). Why is it that this particle is on the left edge of the clause in English, but on the right edge in Japanese? Kayne suggests that in Japanese, the whole of the clause (apart from the question particle in C) has moved to the [Spec,CP] position. So, the structure for the Japanese example above is something like the following:

- [CP [John-wa nani-o kaimasita] C ka

Now it is clear why Japanese does not have wh-movement — the [Spec,CP] position is already filled, so no wh-phrase can move to it. We therefore predict a seemingly obscure relationship between surface word order and the possibility of wh-movement. A possible alternative to the antisymmetric explanation could be based on the difficulty of parsing languages with rightward movement.[5]

Dynamic antisymmetry

A weak version of the theory of antisymmetry (Dynamic antisymmetry) has been proposed by Andrea Moro, which allows the generation of non-LCA compatible structures (points of symmetry) before the hierarchical structure is linearized at Phonetic Form. The unwanted structures are then rescued by movement: deleting the phonetic content of the moved element would neutralize the linearization problem.[6] From this perspective, Dynamic Antisymmetry aims at unifying movement and phrase structure, which otherwise would be two independent properties that characterize all human language grammars.

Antisymmetry and ternary branching

In a recent manuscript, Kayne (2010) has proposed recasting the antisymmetry of natural language as a condition on "Merge", the operation which combines two linguistic elements into one complex linguistic element.[7] Kayne proposes that merging a head H and its complement C yields an ordered pair  (rather than the standard symmetric set {H,C}).

(rather than the standard symmetric set {H,C}).  involves immediate temporal precedence (or immediate linear precedence), so that H immediately precedes (i-precedes) C. Kayne proposes furthermore that when a specifier S merges, it forms an ordered pair with the head directly,

involves immediate temporal precedence (or immediate linear precedence), so that H immediately precedes (i-precedes) C. Kayne proposes furthermore that when a specifier S merges, it forms an ordered pair with the head directly,  , or S i-precedes H. Invoking i-precedence prevents more than two elements from merging with H; only one element can i-precede H (the specifier), and H can i-precede only one element (the complement).

, or S i-precedes H. Invoking i-precedence prevents more than two elements from merging with H; only one element can i-precede H (the specifier), and H can i-precede only one element (the complement).

Kayne (2010) notes that  is not mappable to a tree structure, since H would have two mothers, and that it has the consequence that

is not mappable to a tree structure, since H would have two mothers, and that it has the consequence that  and

and  would seem to be constituents. He suggests that

would seem to be constituents. He suggests that  is replaced by

is replaced by  , "with an ordered triple replacing the two ordered pairs and then being mappable to a ternary-branching tree" (pp. 17). Kayne goes on to say, "This would lead to seeing my [(1981)][8] arguments for binary branching to have two subcomponents, the first being the claim that syntax is n-ary branching with n having a single value, the second being that that value is 2. Mapping [

, "with an ordered triple replacing the two ordered pairs and then being mappable to a ternary-branching tree" (pp. 17). Kayne goes on to say, "This would lead to seeing my [(1981)][8] arguments for binary branching to have two subcomponents, the first being the claim that syntax is n-ary branching with n having a single value, the second being that that value is 2. Mapping [ to

to  ] would retain the first subcomponent and replace 2 by 3 in the second, arguably with no loss in restrictiveness."

] would retain the first subcomponent and replace 2 by 3 in the second, arguably with no loss in restrictiveness."

Theoretical arguments

According to Kayne's Antisymmetry theory, there is no head-directionality parameter as such: it is claimed that at an underlying level, all languages are head-initial. In fact, it is argued that all languages have the underlying order Specifier-Head-Complement. Deviations from this order are accounted for by different syntactic movements applied by languages.

Kayne argues that a theory that allows both directionalities would imply an absence of asymmetries between languages, whereas in fact languages are found not to be symmetrical in many respects. Some examples of linguistic asymmetries which may be cited in support of the theory (although they do not concern head direction) are listed below.

- Hanging topics appear at the start of sentences, as in "Henry – I've known that guy for a long time".[9] They are not attested at the end of sentences.[10]

- Number agreement is stronger when the noun phrase precedes the verb (Greenberg's Universal 33). Examples of this are found in English sentences such as There's books on the table, where the verb frequently fails to agree with the following plural noun, and in French and Italian compound tenses,[11] where the past participle may agree with a preceding direct object but not with a following one.

- Relative clauses which precede the noun (as in Chinese and Japanese) tend to differ from those that follow the noun: they more often lack complementizers (akin to English that) or relative pronouns, and are more likely to be non-finite (this can be found, for example, in Quecha.[12])

- Other areas in which asymmetries are found, according to Kayne, include clitics and clitic dislocation, serial verb constructions, coordination, and forward and backward pronominalization.

.png)

In arguing for a universal underlying Head-Complement order, Kayne uses the concept of a probe-goal search (based on the Minimalist program). The idea of probes and goals in syntax is that a head acts as a probe and looks for a goal, namely its complement. Kayne proposes that the direction of the probe-goal search must share the direction of language parsing and production.[13] Parsing and production proceed in a left-to-right direction: the beginning of sentence is heard or spoken first, and the end of the sentence is heard or spoken last. This implies (according to the theory) an ordering whereby probe comes before goal, i.e. head precedes complement.

Kayne's theory also addresses the position of the specifier of a phrase. He represents the relevant scheme as follows:[14]

- S H [c...

S...]

The specifier, at first internal to the complement, is moved to the unoccupied position to the left of the head. In terms of merged pairs, this structure can also be represented as:

- <S, H> <H, C>

This process can be mapped onto X-bar syntactic trees as shown in the diagram to the right.

Antisymmetry, then, leads to a universal Specifier-Head-Complement order. The many cases of different ordering found in various languages would have to be explained by syntactic movement away from this underlying base order. It has been pointed out, though, that in predominantly head-final languages such as Japanese and Basque, this would involve complex and massive leftward movement, which is not in accordance with the ideal of grammatical simplicity.[15] An example of the type of movement scheme that would need to be envisaged is provided by Tokizaki:[16]

a. [CP C [IP ... [VP V [PP P [NP N [Genitive Affix Stem]]]]]] b. [CP C [IP ... [VP V [PP P [NP N [Genitive Stem Affix]]]]]] c. [CP C [IP ... [VP V [PP P [NP [Genitive Stem Affix] N]]]]] d. [CP C [IP ... [VP V [PP [NP [Genitive Stem Affix] N] P]]]] e. [CP C [IP ... [VP [PP [NP [Genitive Stem Affix] N] P] V]]] f. [CP [IP ... [VP [PP [NP [Genitive Stem Affix] N] P] V]] C] |

Here, at each phrasal level in turn, the head of the phrase moves from left to right position relative to its complement. The eventual result reflects the ordering of complex nested phrases found in a language like Japanese.

An attempt to provide evidence for Kayne's scheme is made by Lin,[17] who considered Standard Chinese sentences with the sentence-final particle le. This particle is taken to convey perfect aspectual meaning, and thus to be the head of an aspect phrase, having the verb phrase as its complement. If phrases are always to be underlyingly head-initial, then a case like this must entail movement, since the particle comes after the verb phrase. It is proposed that here the complement moves into specifier position, which precedes the head.

As evidence for this, Lin considers (among others) wh-adverbials such as zenmeyang ("how?"). Based on prior work by Huang,[18] it is postulated that (a) adverbials of this type are subject to movement at Logical Form (LF) level (even though, in Chinese, they do not display wh-movement at surface level); and (b) movement is not possible from within a non-complement (Huang's Condition on Extraction Domain or CED). This would imply that zenmeyang could not appear in a verb phrase with sentence-final le, assuming the above analysis, since that verb phrase has moved into a non-complement (specifier) position, and thus further movement (such as that which zenmeyang is required to undergo at LF level) is not possible. Such a restriction on the occurrence of zenmeyang is indeed found:[19]

(a) Zhangsan zenmeyang xiu che?

Zhangsan how repair car

"How does Zhangsan repair the car?"

(b) *Zhangsan zenmeyang xiu che le?

Zhangsan how repair car PF

("How has Zhangsan repaired the car?") |

Sentence (b), in which zenmeyang co-occurs with sentence-final le, is found to be ungrammatical. Lin cites this and other related findings as evidence that the above analysis is correct, supporting the view that Chinese aspect phrases are deeply head-initial.

Surface true approach

According to the "surface true" viewpoint, analysis of head direction must take place at the level of surface derivations, or even the Phonetic Form (PF), i.e. the order in which sentences are pronounced in natural speech. This rejects the idea of an underlying ordering which is then subject to movement, as posited in the Antisymmetry theory and in certain other approaches. In a 2008 article, the linguist Marc Richards argued that a head parameter must only reside at PF, as it is unmaintainable in its original form as a structural parameter.[20] In this approach the relative positions of head and complement that are actually attested at this surface level, which are found to show variation both between and within languages (see above), must be treated as the "true" orderings.

Existence of true head-final languages

Takita (2009) argues against the conclusion of Kayne's Antisymmetry Theory which states that all languages are head-initial at an underlying level. He claims that a language such as Japanese is truly head-final, since the mass movement which would be required to take an underlying head-initial structure to the head-final ones actually found in such languages would violate other constraints. It is implied that such languages are likely following a head-final parameter value, as originally conceived. (For a head-initial/Antisymmetry analysis of Japanese, see Kayne 2003.[21])

Takita's argument is based on the analysis provided by Lin concerning Chinese (see above). Since surface head-final structures are derived from underlying head-initial structures from the act of moving the complements, further extraction from within the moved complement violates CED.

One of the examples of movement which Takita looks at is that of VP-fronting in Japanese. Grammatically, there is not a significant difference between the sentence without VP-fronting (a) and the sentence where the VP moves to the matrix clause (b).[22]

a. [CP1 Taro-ga [CP2[IP2 Hanako-ga [VP2 hon-o sute]-sae sita to] omotteiru]

Taro-NOM Hanako-NOM book-ACC discard-even did C think

'Taro thinks [that Hanako [even discarded his books]]'

(Takita 2009 57: (33a)

b. [CP1[VP2 Hon-o sute]-saei Taro-ga [CP2[IP2 Hanako-ga sita] to] omotteiru

book-ACC discard-even Taro-NOM Hanako-NOM did C think

'[Even discarded his books], Taro thinks [that Hanako did ti]'

(Takita 2009 57: (33b) |

In (b), the fronted VP precedes the matrix subject, confirming that the VP is located in the matrix clause. If Japanese were underlyingly head-initial, (b) should not be grammatical because it allows for extraction of an element (VP2) from the moved complement (CP2).[22]

Thus Takita shows that surface head-final structures in Japanese do not block movement, as they do in Chinese. He concludes that, because Japanese does not block movement as shown in previous sections, it is a genuinely head-final language, and not derived from an underlying, head-initial structure. These results imply that Universal Grammar is equipped with the binary head-directionality, and is not antisymmetric. Takita briefly applies the same tests to Turkish, another seemingly head-final language, and finds similar results.[23]

References and footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kayne, Richard S. (1994). The Antisymmetry of Syntax. Linguistic Inquiry Monograph Twenty-Five. MIT Press.

- ↑ Li, Yafei (2005). A Theory of the Morphology-Syntax Interface. MIT Press.

- ↑ Since any rightward movement must also be downward movement if there are no rightward specifiers or right adjunction, and downward movement is generally assumed to be illicit.

- ↑ Jamal Ouhalla (1999). Introducing Transformational Grammar (Second Edition). Arnold/Oxford University Press. (See p. 461 for the Japanese example.)

- ↑ Neeleman, Ad & Peter Ackema (2002). "Effects of Short-Term Storage in Processing Rightward Movement" In S. Nooteboom et al. (eds.) Storage and Computation in the Language Faculty. Dordrecht: Kluwer. Pages 219-256.

- ↑ Moro, A. 2000 Dynamic Antisymmetry, Linguistic Inquiry Monograph Series 38, MIT press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- ↑ Kayne, Richard S. (2010). "Why are there no directionality parameters?" In WCCFL XXVIII. Available on http://ling.auf.net/lingBuzz/001100

- ↑ Kayne, Richard S. (1981) “Unambiguous Paths,” in Robert May and Jan Koster (eds.) Levels of Syntactic Representation. Dordrecht: Kluwer. Pages 143-183

- ↑ Nolda, Andreas (2004). Topics Detached to the Left: On ‘Left Dislocation’, ‘Hanging Topic’, and Related Constructions in German. Berlin: ZAS Papers in Linguistics. pp. 423–448.

- ↑ Kayne (2010), p. 4.

- ↑ Kayne (2010), p. 7.

- ↑ Courtney, Ellen H. (2011). "Learning to produce Quechua relative clauses". Acquisition of Relative Clauses : Processing, typology and function. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 150.

- ↑ Kayne (2010), p. 12.

- ↑ Kayne (2010), p. 15.

- ↑ Elordieta, Arantzazu (2014). Biberauer, T.; Sheehan, M., eds. "On the relevance of the Head Parameter in a mixed OV language". Theoretical Approaches to Disharmonic Word Order (Oxford Scholarship Online), p. 5.

- ↑ Tokizaki, Hisao (2011). "The nature of linear information in the morphosyntax-PF interface". English Linguistics 28 (2), p. 238.

- ↑ Lin, Tzong-Hong J. (2006), "Complement-to-specifier movement in Mandarin Chinese". Ms., National Tsing Hua University.

- ↑ Huang, C-T. J. (1982). "Logical relations in Chinese and the theory of grammar". PhD dissertation, MIT.

- ↑ Takita, Kensuke (2009). "If Chinese is head-initial, Japanese cannot be". Journal of East Asian Linguistics 18 (1), p. 44.

- ↑ Richards, Marc D. (2008). "Desymmetrization: Parametric variation at the PF-Interface". The Canadian Journal of Linguistics 53 (2-3), p. 283.

- ↑ Kayne, Richard S. (2003). "Antisymmetry and Japanese". English Linguistics 20: 1–40.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Takita (2009), p. 57.

- ↑ Takita (2009), p. 59.