Antiguan racer

| Antiguan racer | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Colubridae |

| Subfamily: | Dipsadinae |

| Genus: | Alsophis |

| Species: | A. antiguae |

| Binomial name | |

| Alsophis antiguae Parker, 1933[1] | |

| |

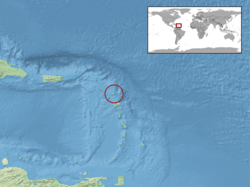

The Antiguan racer (Alsophis antiguae) is a harmless rear-fanged (opisthoglyphous) grey-brown snake found only on Great Bird Island off the coast of Antigua, a small Caribbean island, thus colloquially named the "Antigua racer snake". It is among the rarest snakes in the world. However, in the last 15 years, conservation efforts have boosted numbers from an estimated 50 to some 500 snakes.

Taxonomy

The Antiguan racer is a snake which belongs to the family Colubridae, which includes about half of the world's known snake species. It belongs to the genus Alsophis, which contains several species of West Indian racers. Most of the members of its genus are threatened or extinct.[2]

Description

This racer exhibits sexual dimorphism.[2] The adult racer is about one meter long, with females being larger than the males.[2] The males are a dark brown with light creamy markings, while the females are silvery-gray with pale brown patches and markings.[2] Females also have larger heads than the males.[3]

Distribution and habitat

The Antiguan racer is only found on Great Bird Island, a small island three kilometers off of the northeast coast of Antigua.[4] The island is extremely small at only 20 acres (81,000 m2).[4] It prefers to live in shady areas with logs and dense undergrowth, although it is often found on sandbars, rocky ridges, and forests.[2]

Ecology and behavior

The Antiguan racer is harmless to humans and has a gentle temperament.[2] It is diurnal, being active from dawn to dusk except for a rest around mid-day.[2] At night, it rests in a hidden shelter.[2] The Antiguan racer has a poor resistance to common diseases not found in Antigua, which has ended some attempts at captive breeding.[5]

The racer primarily eats a diet of lizards, including the local Antiguan Ground Lizard.[2] While the species sometimes hunts for its food, it is typically an ambush predator, waiting for prey with most of its body buried beneath leaves.[2] The racer typically eats a lizard once every two weeks.[2]

Relationship with Humans

In the centuries before the Europeans arrived in Antigua, the Antiguan racers were numerous and widespread. The thick forest that covered the island teemed with lizards, the snakes' favored prey, and the racer had no natural predators to threaten them.[6]

In the late 15th century, European settlers began to colonize and develop Antigua and Barbuda for huge plantations of sugar cane. The ships which brought slaves to the island also brought rats. Feasting on the sugar cane and, among other things, the eggs of the Antiguan racer, the rat population rocketed. By the end of the 19th century, the island was overpopulated with rats.[6]

The plantation owners, desperate to rid themselves of the rats, came up with a plan to introduce Asian mongooses to kill the rats. However, they failed to realize that black rats (Rattus rattus) are mainly nocturnal, while the mongooses prefer to hunt during the day. Instead of eating the rats, the mongooses instead ate the native birds, frogs and Antiguan racers. Within sixty years, the snake had vanished completely from Antigua and most of its offshore islands and many believed that it had become extinct.[6]

However, a few Antiguan racers survived on a tiny mongoose-free island known Great Bird Island. In the early 1990s, a local naturalist from the Island Resources Foundation met a zoologist from Fauna & Flora International. Together, they visited Great Bird Island and rediscovered the snake.[6] However, there were only 50 snakes alive in 1995.[7]

Conservation work quickly got underway with surveys of the snake's biology. In December 1995, rat poison was laid across Great Bird Island to eliminate the rats which were threatening the racers.[8] The effort succeeded. In 1996, five adult racers were collected and sent to the Jersey Zoo for the first attempt at captive breeding.[5] The female racers laid eleven eggs with five hatching, but proved to be difficult to keep in captivity due to their feeding habits and low resistance to diseases. Nine of the ten captive racers died because of the common snake mite.[5]

However, the eradication of rats and mongooses on Great Bird Island led to a population explosion, with the number of racers on the island doubling in two years.[9] However, 20% of the racers were underweight because of the lack of number of lizards to maintain the population levels.[9] Efforts began to clean other offshore islands of Antigua of rats and mongooses to reintroduce the snake so that the population can continue to grow.[9]

It is currently threatened by hurricanes, such as Hurricane Luis and Hurricane Georges, flooding, drought, and inbreeding due to low genetic diversity.[10]

References

- ↑ Day, M. (2007). "Alsophis antiguae". 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 "The S Files". The Antiguan Racer Conservation Project. 2001. Archived from the original on 31 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ↑ "Antiguan Racer". ARKive. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "The Last Resort". The Antiguan Racer Conservation Project. 2001. Archived from the original on 14 November 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Safety Net". Antiguan Racer Conservation Project. 2001. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "Hiss-tory". Antiguan Racer Conservation Project. 2001. Archived from the original on 31 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ↑ "The Project: Mission Impossible?". The Antiguan Racer Conservation Project. 2001. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ↑ "Removal Service". Antiguan Racer Conservation Project. 2001. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Safety Net". Antiguan Racer Conservation Project. 2001. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ "Problems". Antiguan Racer Conservation Project. 2001. Archived from the original on 25 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-21.