Antiaromaticity

Antiaromaticity is a characteristic of a cyclic molecule with a π electron system that has higher energy due to the presence of 4n electrons in it. Unlike aromatic compounds, which follow Hückel's rule ([4n+2] π electrons)[1] and are highly stable, antiaromatic compounds are highly unstable and highly reactive. To avoid the instability of antiaromaticity, molecules may change shape, becoming non-planar and therefore breaking some of the π interactions. In contrast to the diamagnetic ring current present in aromatic compounds, antiaromatic compounds have a paramagnetic ring current, which can be observed by NMR spectroscopy.

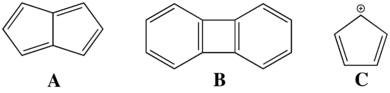

Examples of antiaromatic compounds are pentalene (A), biphenylene (B), cyclopentadienyl cation (C). The prototypical example of antiaromaticity, cyclobutadiene, is the subject of debate, with some scientists arguing that antiaromaticity is not a major factor contributing to its destabilization.[2] Cyclooctatetraene is an example of a molecule adopting a non-planar geometry to avoid the destabilization that results from antiaromaticity. If it were planar, it would have a single eight-electron π system around the ring, but it instead adopts a boat-like shape with four individual π bonds.[3] Because antiaromatic compounds are often short-lived and difficult to work with experimentally, antiaromatic destabilization energy is often modeled by simulation rather than by experimentation.[2]

Definition

The term 'antiaromaticity' was first proposed by Ronald Breslow in 1967 as "a situation in which a cyclic delocalisation of electrons is destabilising".[4] The IUPAC criteria for antiaromaticity are as follows:[5]

1. The molecule must be cyclic.

2. The molecule must be planar.

3. The molecule must have a complete conjugated π-electron system within the ring.

4. The molecule must have 4n π-electrons where n is any integer within the conjugated π-system.

This differs from aromaticity in the fourth criterion: aromatic molecules have 4n +2 π-electrons in the conjugated π system and therefore follow Hückel’s rule. Non-aromatic molecules are either noncyclic, nonplanar, or do not have a complete conjugated π system within the ring.

| Aromatic | Antiaromatic | Non-aromatic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic? | Yes | Yes | Will fail at least one of these |

| Has completely conjugated system of p orbitals in ring of molecule? | Yes | Yes | |

| Planar? | Yes | No | |

| How many π electrons in the conjugated system? | 4n+2 (i.e., 2, 6, 10, …) | 4n (4, 8, 12, …) | N/A |

Having a planar ring system is essential for maximizing the overlap between the p orbitals which make up the conjugated π system. This explains why being a planar, cyclic molecule is a key characteristic of both aromatic and antiaromatic molecules. However, in reality, it is difficult to determine whether or not a molecule is completely conjugated simply by looking at its structure: sometimes molecules can distort in order to relieve strain and this distortion has the potential to disrupt the conjugation. Thus, additional efforts must be taken in order to determine whether or not a certain molecule is genuinely antiaromatic.[6]

An antiaromatic compound may demonstrate its antiaromaticity both kinetically and thermodynamically. As will be discussed later, antiaromatic compounds experience exceptionally high chemical reactivity (being highly reactive is not “indicative” of an antiaromatic compound, it merely suggests that the compound could be antiaromatic). An antiaromatic compound may also be recognized thermodynamically by measuring the energy of the cyclic conjugated π electron system. In an antiaromatic compound, the amount of conjugation energy in the molecule will be significantly higher than in an appropriate reference compound.[7]

In reality, it is recommended that one analyze the structure of a potentially antiaromatic compound extensively before declaring that it is indeed antiaromatic. If an experimentally determined structure of the molecule in question does not exist, a computational analysis must be performed. The potential energy of the molecule should be probed for various geometries in order to assess any distortion from a symmetric planar conformation.[6] This procedure is recommended because there have been multiple instances in the past where molecules which appear to be antiaromatic on paper turn out to be not truly so in actuality. The most famous (and heavily debated) of these molecules is cyclobutadiene, as is discussed later.

Examples of antiaromatic compounds are pentalene (A), biphenylene (B), cyclopentadienyl cation (C). The prototypical example of antiaromaticity, cyclobutadiene, is the subject of debate, with some scientists arguing that antiaromaticity is not a major factor contributing to its destabilization.[2] Cyclooctatetraene appears at first glance to be antiaromatic, but is an excellent example of a molecule adopting a non-planar geometry to avoid the destabilization that results from antiaromaticity.[3] Because antiaromatic compounds are often short-lived and difficult to work with experimentally, antiaromatic destabilization energy is often modeled by simulation rather than by experimentation.[2]

Antiaromaticity in NMR Spectra

The paramagnetic ring current resulting from the electron delocalization in antiaromatic compounds can be observed by NMR. This ring current leads to a deshielding (downfield shift) of nuclei inside the ring and a shielding (upfield shift) of nuclei outside the ring. [12]annulene is an antiaromatic hydrocarbon that is large enough to have protons both inside and outside of the ring. The chemical shift for the protons inside its ring is 5.91 ppm and that for the protons outside the ring is 7.86 ppm, compared to the normal range of 4.5-6.5 ppm for nonaromatic alkenes. This effect is of a smaller magnitude than the corresponding shifts in aromatic compounds.[8]

Many aromatic and antiaromatic compounds (benzene and cyclobutadiene) are too small to have protons inside of the ring, where shielding and deshielding effects can be more diagnostically useful in determining if a compound is aromatic, antiaromatic, or nonaromatic. Nucleus Independent Chemical Shift (NICS) analysis is a method of computing the ring shielding (or deshielding) at the center of a ring system to predict aromaticity or antiaromaticity. A negative NICS value is indicative of aromaticity and a positive value is indicative of antiaromaticity.[9]

Examples of Antiaromaticity

While there are multitudes of molecules in existence which would appear to be antiaromatic on paper, the number of molecules are antiaromatic in actuality is considerably less. This is compounded by the fact that one cannot typically make derivatives of antiaromatic molecules by adding more antiaromatic hydrocarbon rings, etc. because the molecule typically loses either its planar nature or its conjugated system of π-electrons and becomes nonaromatic.[10] In this section, only examples of antiaromatic compounds which are non-disputable are included.

Pentalene is an antiaromatic compound which has been well-studied both experimentally and computationally for decades. It is dicyclic, planar and has eight π-electrons, fulfilling the IUPAC definition of antiaromaticity. Pentalene’s dianionic and dicationic states are aromatic, as they follow Hückel’s 4n +2 π-electron rule.[11]

Like its relative [12]annulene, hexadehydro[12]annulene is also antiaromatic. The structure of hexadehydro[12]annulene has been studied computationally via ab initio and density functional theory calculations and is confirmed to be antiaromatic.[12]

Cyclobutadiene

Cyclobutadiene is the classic textbook example of an antiaromatic compound. It is conventionally understood to be planar, cyclic and has a 4n conjugated π-electron system.

However, it has long been questioned if cyclobutadiene is genuinely antiaromatic and recent discoveries have suggested that it may not be. Cyclobutadiene is particularly destabilized and this was originally attributed to antiaromaticity. However, none of its 4n π-electron relatives (cyclooctatetraene, etc.) had even close to as much destabilization, suggesting there was something more going on in the case of cyclobutadiene. It was found that a combination of angle strain, torsional strain, and Pauli repulsion leads to the extreme destabilization experienced in cyclobutadiene.[2]

Further erasing the label of antiaromaticity is the argument that the molecule does not even have delocalized electrons. Cyclobutadiene adopts more double bond character in two of its parallel bonds than others, giving it a rectangular shape as opposed to the square shape that it is represented with on paper.[3] This inequality in the bonds prevents the “π” electrons from delocalizing and forming the conjugated “π” electron system required for an antiaromatic compound.

This discovery is awkward in that it contradicts basic teachings of antiaromaticity. At this point of time, it is presumed that cyclobutadiene will continue to be used to introduce the concept of antiaromaticity in textbooks as a matter of convenience, even though classifying it as antiaromatic technically may not be accurate.

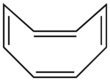

Cyclooctatetraene

Another example of a molecule which is not antiaromatic even though it might initially appear to be so is cyclooctatetraene. Cyclooctatetraene assumes a tub (i.e., boat-like) conformation. As it is not planar, even though it has 4n π-electrons, these electrons are not delocalized and conjugated. The molecule is therefore nonaromatic.[3]

Examples of Antiaromaticity Affecting Reactivity

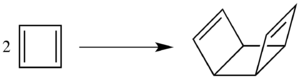

Antiaromatic compounds, often being very unstable, can be highly reactive in order to relieve the antiaromatic destabilization. Cyclobutadiene, for example, rapidly dimerizes with no potential energy barrier via a Diels-Alder reaction to form tricyclooctadiene[13] While the antiaromatic character of cyclobutadiene is the subject of debate, the relief of antiaromaticity is usually invoked as the driving force of this reaction.

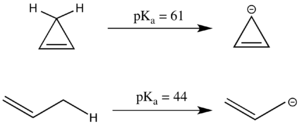

Antiaromaticity can also have a significant effect on pKa. The linear compound 1-propene has a pKa of 44, which is relatively acidic for an sp3 carbon center because the resultant allyl anion can be resonance stabilized. The analogous cyclic system appears to have even more resonance stabilized, as the negative charge can be delocalized across three carbons instead of two. However, the cyclopropenyl anion has 4 π electrons in a cyclic system and in fact has a substantially higher pKa than 1-propene because it is antiaromatic and thus destabilized.[3] Because antiaromatic compounds are often short-lived and difficult to work with experimentally, antiaromatic destabilization energy is often modeled by simulation rather than by experimentation.[2]

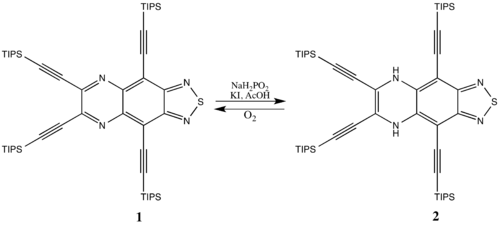

Some antiaromatic compounds are stable, especially larger cyclic systems (in which the antiaromatic destabilization is not as substantial). For example, the aromatic species 1 can be reduced to 2 with a relatively small penalty for forming an antiaromatic system. The antiaromatic 2 does revert to the aromatic species 1 over time by reacting with oxygen in the air because the aromaticity is preferred.[14]

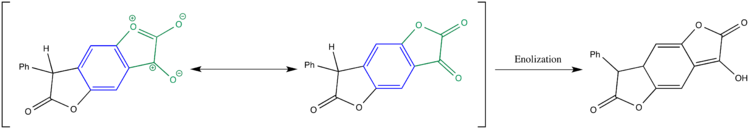

The loss of antiaromaticity can sometimes be the driving force of a reaction. In the following keto-enol tautomerization, the product enol is more stable than the original ketone even though the ketone contains an aromatic benzene moiety (blue). However, there is also an antiaromatic lactone moiety (green). The relief of antiaromatic destabilization provides a driving force that outweighs even the loss of an aromatic benzene.[15]

References

- ↑ "IUPAC Gold Book: Antiaromaticity". Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Wu, Judy I-Chia; Yirong Mo; Francesco Alfredo Evangelista; Paul von Ragué Schleyer (June 2012). "Is cyclobutadiene really highly destablilized by antiaromaticity?". Chem. Comm. 48: 8437–8439. doi:10.1039/c2cc33521b.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Anslyn, Eric V. (2006). Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. University Science Books. ISBN 978-1-891389-31-3.

- ↑ Breslow, Ronald.; Brown, John.; Gajewski, Joseph J. (August 1967). "Antiaromaticity of cyclopropenyl anions". Journal of the American Chemical Society 89 (17): 4383–4390. doi:10.1021/ja00993a023.

- ↑ Moss, G. P.; P. A. S. Smith and D. Tavernier (1995). "Glossary of class names of organic compounds and reactivity intermediates based on structure". Rue and Applied Chemistry 67: 1307–1375. doi:10.1351/pac199567081307.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Podlogar, Brent L.; William A. Glauser; Walter R. Rodriguez; Douglas J. Raber (1988). "A Conformational Criterion for Aromaticity and Antiaromaticity". J. Org. Chem. 53: 2127–2129. doi:10.1021/jo00244a059.

- ↑ Breslow, Ronald (December 1973). "Antiaromaticity". Accounts of Chemical Research 6 (12): 393–398. doi:10.1021/ar50072a001.

- ↑ Alkorta, Ibon; Isabel Rozas, Jose Elguero. (June 1992). "An ab initio study of the NMR properties (absolute shielding and NICS) of a series of significant aromatic and antiaromatic compouds". Teterahedron 118: 880–885. doi:10.1021/ja921663m.

- ↑ What is aromaticity? Paul von Ragué Schleyer and Haijun Jiao Pure & Appl. Chem., Vol. 68, No. 2, pp. 209-218, 1996 Link

- ↑ Jusélius, Jonas; Dage Sundholm (2008). "Polycyclic antiaromatic hydrocarbons". Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10: 6630–6634. doi:10.1039/b808082h.

- ↑ Liu, Binyao; Wei Shen; Xiaohua Xie; Lidan Deng; Ming Li (August 2011). "Theoretical analysis on geometries and electronic structures of antiaromatic pentalene and its N-substituted derivatives: monomer, oligomers and polymer". Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry 25 (4): 278–286. doi:10.1002/poc.1907.

- ↑ Jusélias, Jonas; Dage Sundholm (2001). "The aromaticity and antiaromaticity of dehydroannulenes". Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 3: 2433–2437. doi:10.1039/B101179K.

- ↑ Yi, Li; K. N. Houk. (July 2001). "The Dimerization of Cyclobutadiene. An ab Initio CASSCF Theoretical Study". JACS 57: 6043–6049. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)00585-3.

- ↑ A Thiadiazole-Fused N,N-Dihydroquinoxaline: Antiaromatic but Isolable Shaobin Miao, Paul v. R. Schleyer, Judy I. Wu, Kenneth I. Hardcastle, and Uwe H. F. Bunz Org. Lett.; 2007; 9(6) pp 1073 - 1076; (Letter) doi:10.1021/ol070013i

- ↑ Lawrence, Anthony J.; Michael G, Hutchings, Alan R. Kennedy, Joseph J. W. McDouall. (2010). "Benzodifurantrione: A Stable Phenylogous Enol". JOC 75: 690–701. doi:10.1021/jo9022155.