Antenna aperture

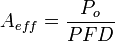

In electromagnetics and antenna theory, antenna aperture or effective area is a measure of how effective an antenna is at receiving the power of radio waves. The aperture is defined as the area, oriented perpendicular to the direction of an incoming radio wave, which would intercept the same amount of power from that wave as is produced by the antenna receiving it. At any point, a beam of radio waves has an irradiance or power flux density (PFD) which is the amount of radio power passing through a unit area. If an antenna delivers an output power of Po watts to the load connected to its output terminals when irradiated by a uniform field of power density PFD watts per square metre, the antenna's aperture Aeff in square metres is given by:[1]

.

.

So the power output of an antenna in watts is equal to the power density of the radio waves in watts per square metre, multiplied by its aperture in square metres. The larger an antenna's aperture is, the more power it can collect from a given field of radio waves. To actually obtain the predicted power available Po, the polarization of the incoming waves must match the polarization of the antenna, and the load (receiver) must be impedance matched to the antenna's feedpoint impedance.

Although this concept is based on an antenna receiving a radio frequency wave, knowing Aeff directly supplies the (power) gain of that antenna. Due to reciprocity, an antenna's gain in receiving and transmitting are identical. Therefore Aeff can just as well be used to compute the performance of a transmitting antenna. Note that Aeff is a function of the direction of the radio wave relative to the orientation of the antenna, since the gain of an antenna varies according to its radiation pattern. When no direction is specified, Aeff is understood to refer to its maximum value, with the antenna oriented so its main lobe, the axis of maximum sensitivity, is directed toward the source.

Aperture efficiency

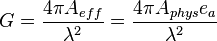

In general, the aperture of an antenna is not directly related to its physical size.[2] However some types of antennas, for example parabolic dishes and horns, have a physical aperture (opening) which collects the radio waves. In these aperture antennas, the effective aperture Aeff must always be less than the area of the antenna's physical aperture Aphys, as can be seen from the definition above. An antenna's aperture efficiency, ea is defined as the ratio of these two areas:

The aperture efficiency is a dimensionless parameter between 0 and 1.0 that measures how close the antenna comes to using all the radio power entering its physical aperture. If the antenna were perfectly efficient, all the radio power falling within its physical aperture would be converted to electrical power delivered to the load attached to its output terminals, so these two areas would be equal Aeff = Aphys and the aperture efficiency would be 1.0. But all antennas have losses, such as power dissipated as heat in the resistance of its elements, nonuniform illumination by its feed, and radio waves scattered by structural supports and diffraction at the aperture edge, which reduce the power output. Aperture efficiencies of typical antennas vary from 0.35 to 0.70 but can range up to 0.90.

Aperture and gain

The directivity of an antenna, its ability to direct radio waves in one direction or receive from a single direction, is measured by a parameter called its gain, which is the ratio of the power received by the antenna to the power that would be received by a hypothetical isotropic antenna, which receives power equally well from all directions.

It can be shown that the aperture of a lossless isotropic antenna, which by definition has unity gain, is:

where λ is the wavelength of the radio waves. So the gain of any antenna is proportional to its aperture:

So antennas with large effective apertures are high gain antennas, which have small angular beam widths. Most of their power is radiated in a narrow beam in one direction, and little in other directions. As receiving antennas, they are most sensitive to radio waves coming from one direction, and are much less sensitive to waves coming from other directions. Although these terms can be used as a function of direction, when no direction is specified, the gain and aperture are understood to refer to the antenna's axis of maximum gain, or boresight.

Friis transmission equation

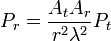

The fraction of the power delivered to a transmitting antenna that is received by a receiving antenna is proportional to the product of the apertures of both the antennas. This is given by a form of the Friis transmission equation:.[2]

where

- Pr is the power delivered by the receiving antenna in watts

- Pt is the power applied to the transmitting antenna in watts

- Ar is the aperture of the receiving antenna in m2

- At is the aperture of the transmitting antenna in m2

- r is the distance between the antenna in m

- λ is the wavelength of the radio waves in m

Thin element antennas

In the case of thin element antennas such as monopoles and dipoles, there is no simple relationship between physical area and effective area. However, the effective areas can be calculated from their power gain figures:[3]

| Wire antenna | Power gain | Effective area |

|---|---|---|

| Short dipole (Hertzian dipole) | 1.5 | 0.1194  2 2 |

| Half-wave dipole | 1.64 | 0.1305  2 2 |

| Quarter-wave monopole | 1.28 | 0.1025  2 2 |

This assumes that the monopole antenna is mounted above an infinite ground plane and that the antennas are lossless. When resistive losses are taken into account, particularly with small antennas, the antenna gain might be substantially less than the directivity, and the effective area is less by the same factor.[4]

Effective length

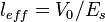

For antennas which are not defined by a physical area, such as monopoles and dipoles consisting of thin rod conductors, the aperture bears no obvious relation to the size or area of the antenna. An alternate measure of antenna gain that has a greater relationship to the physical structure of such antennas is effective length leff measured in metres, which is defined for a receiving antenna as:[5]

where

- V0 is the open circuit voltage appearing across the antenna's terminals

- Es is the electric field strength of the radio signal, in volts per metre, at the antenna.

The longer the effective length the more voltage and therefore the more power the antenna will receive. Note, however, that an antenna's gain or Aeff increases according to the square of leff, and that this proportionality also involves the antenna's radiation resistance. Therefore this measure is of more theoretical than practical value and is not, by itself, a useful figure of merit relating to an antenna's directivity.

References

- ↑ Bakshi, K.A.; A.V.Bakshi, U.A.Bakshi (2009). Antennas And Wave Propagation. Technical Publications. p. 1.17. ISBN 81-8431-278-4.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Narayan, C.P. (2007). Antennas And Propagation. Technical Publications. p. 51. ISBN 81-8431-176-1.

- ↑ Orfanidis, Sophocles J. (2010) Electromagnetic Waves and Antennas chapter 15 page 609, retrieved 2011-04-05 from http://www.ece.rutgers.edu/~orfanidi/ewa/

- ↑ Weeks, W.L. (1968) Antenna Engineering, McGraw Hill Book Company, chapters 8, pp. 297-299 and 9, pp. 343-346.

- ↑ Rudge, Alan W. (1982). The Handbook of Antenna Design, Vol. 1. USA: IET. p. 24. ISBN 0-906048-82-6.