Animal husbandry

|

| Agriculture |

|---|

| General |

|

| History |

| Types |

| Categories |

|

| Agriculture / Agronomy portal |

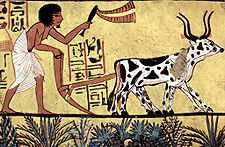

Animal husbandry is the management and care of farm animals by humans for profit, in which genetic qualities and behaviour, considered to be advantageous to humans, are further developed. The term can refer to the practice of selectively breeding and raising livestock to promote desirable traits in animals for utility, sport, pleasure, or research.[1]

History of breeding

Animal husbandry has been practiced for thousands of years since the first domestication of animals. Selective breeding for desired traits was first established as a scientific practice by Robert Bakewell during the British Agricultural Revolution in the 18th century. One of his most important breeding programs was with sheep. Using native stock, he was able to quickly select for large, yet fine-boned sheep, with long, lustrous wool. The Lincoln Longwool was improved by Bakewell and in turn the Lincoln was used to develop the subsequent breed, named the New (or Dishley) Leicester. It was hornless and had a square, meaty body with straight top lines.[2] These sheep were exported widely and have contributed to numerous modern breeds.

Under his influence, English farmers began to breed cattle for use primarily as beef for consumption - (previously, cattle were first and foremost bred for pulling ploughs as oxen). Long-horned heifers were crossed with the Westmoreland bull to eventually create the Dishley Longhorn. Over the following decades, farm animals increased dramatically in size and quality. In 1700, the average weight of a bull sold for slaughter was 370 pounds (168 kg). By 1786, that weight had more than doubled to 840 pounds (381 kg).

Animal herding professions specialized in the 19th century to include the cowboys of the United States and Canada, charros and vaqueros of Mexico, gauchos and huasos of South America, and the farmers and stockmen of Australia.

In more modern times herds are tended on horses, all-terrain vehicles, motorbikes, four-wheel drive vehicles, and helicopters, depending on the terrain and livestock concerned. Today, herd managers often oversee thousands of animals and many staff. Farms, stations and ranches may employ breeders, herd health specialists, feeders, and milkers to help care for the animals.

Breeding techniques

Techniques such as artificial insemination and embryo transfer are frequently used today, not only as methods to guarantee that females breed regularly but also to help improve herd genetics. This may be done by transplanting embryos from high-quality females into lower-quality surrogate mothers - freeing up the higher-quality mother to be reimpregnated. This practice vastly increases the number of offspring which may be produced by a small selection of the best quality parent animals. On the one hand, this improves the ability of the animals to convert feed to meat, milk, or fiber more efficiently, and improve the quality of the final product. On the other, it decreases genetic diversity, increasing the severity of certain disease outbreaks among other risks.

History in Europe

The semi-natural, unfertilized pastures formed by traditional agricultural methods in Europe, were managed and maintained by the grazing and mowing of livestock.[3] Because the ecological impact of this land management strategy is similar to the impact of a natural disturbance, the agricultural system will share many beneficial characteristics with a natural habitat including the promotion of biodiversity.[3] This strategy is declining in the European context due to the intensification of agriculture,[3] and the mechanized chemical based methods that became popular during and following the industrial revolution .

Climate change

Due to the significant contribution of agriculture to the emissions of non-CO2 greenhouse gases methane and nitrous oxide, the relationship between humans and livestock is being analyzed for its potential to help mitigate climate change. Strategies for the mitigation include optimizing the use of gas produced from manure for energy production (biogas).[4]

See also

|

References

Notes

- ↑ "Animal husbandry". Encyclopaedia Brittanica. Retrieved 5 June 2013.Jarman, M.R.; Clark, Grahame; Grigson, Caroline; Uerpmann, H.P.; Ryder, M.L (1976). "Early Animal Husbandry". The Royal Society 275 (936): 85–97. doi:10.1098/rstb.1976.0072.

- ↑ "Robert Bakewell (1725 - 1795)". BBC History. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Pykala, Juha (2000). "Mitigating Human Effects of European Biodiversity Through Traditional Animal Husbandry". Conservation Biology 14 (3): 705–712. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99119.x.

- ↑ Monteny, Gert-Jan; Andre Bannink; David Chadwick (2006). "Greenhouse Gas Abatement Strategies for Animal Husbandry, Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment". Agriculutre, Ecosystems, and Environment 112 (2–3): 163–170. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2005.08.015. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

Bibliography

- Antonio, Saltini. Storia delle scienze agrarie, 4 vols, Bologna 1984-89, ISBN 88-206-2412-5, ISBN 88-206-2413-3, ISBN 88-206-2414-1, ISBN 88-206-2415-X

- Juliet, Clutton Brock. The walking larder. Patterns of domestication, pastoralism and predation, Unwin Hyman, London 1988

- Juliet, Clutton Brock. Horse power: a history of the horse and donkey in human societies, National history Museum publications, London 1992

- Fleming G., Guzzoni M. Storia cronologica delle epizoozie dal 1409 av. Cristo sino al 1800, in Gazzetta medico-veterinaria, I-II, Milano 1871-72

- Hall S and Juliet, Clutton Brock. Two hundred years of British farm livestock, Natural History Museum Publications, London 1988

- Jules, Janick; Noller, Carl H. and Rhyker, Charles L. The Cycles of Plant and Animal Nutrition, in Food and Agriculture, Scientific American Books, San Francisco 1976

- Manger, Louis N. A History of the Life Sciences, M. Dekker, New York, Basel 2002

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Animal husbandry. |

| Look up husbandry in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Breeding. |

- Animal husbandry practices - National Animal Interest Alliance

- Research Institute for Animal Husbandry

- Institute of Genetics and Animal Breeding PAS

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)

- In situ conservation of livestock and poultry, 1992, Online book, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the United Nations Environment Programme

- Dr. Temple Grandin's Web Page Livestock Behaviour, Design of Facilities and Humane Slaughter

| Library resources about Animal husbandry |