Anharmonicity

In classical mechanics, anharmonicity is the deviation of a system from being a harmonic oscillator. An oscillator that is not oscillating in simple harmonic motion is known as an anharmonic oscillator where the system can be approximated to a harmonic oscillator and the anharmonicity can be calculated using perturbation theory. If the anharmonicity is large, then other numerical techniques have to be used.

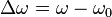

As a result, oscillations with frequencies  and

and  etc., where

etc., where  is the fundamental frequency of the oscillator, appear. Furthermore, the frequency

is the fundamental frequency of the oscillator, appear. Furthermore, the frequency  deviates from the frequency

deviates from the frequency  of the harmonic oscillations. As a first approximation, the frequency shift

of the harmonic oscillations. As a first approximation, the frequency shift  is proportional to the square of the oscillation amplitude

is proportional to the square of the oscillation amplitude  :

:

In a system of oscillators with natural frequencies  ,

,  , ... anharmonicity results in additional oscillations with frequencies

, ... anharmonicity results in additional oscillations with frequencies  .

.

Anharmonicity also modifies the profile of the resonance curve, leading to interesting phenomena such as the foldover effect and superharmonic resonance.

General principle

A generalized version of harmonic oscillator in which the relationship between force and displacement is linear. The harmonic oscillator is a highly idealized system that oscillates with a single frequency, irrespective of the amount of pumping or energy injected into the system. Consequently, the harmonic oscillator's fundamental frequency of vibration is independent of the amplitude of the vibrations. Applications of the harmonic oscillator model abound in various fields, but perhaps the most commonly studied system is the Hooke's law mass-spring system. In the Hooke's law system the restoring force exerted on the mass is proportional to the displacement of the mass from its equilibrium position. This linear relationship between force and displacement mandates that the oscillation frequency of the mass will be independent of the amplitude of the displacement.

In a mechanical anharmonic oscillator, the relationship between force and displacement is not linear but depends upon the amplitude of the displacement. The nonlinearity arises from the fact that the spring is not capable of exerting a restoring force that is proportional to its displacement because of, for example, stretching in the material comprising the spring. As a result of the nonlinearity, the vibration frequency can change, depending upon the system's displacement. These changes in the vibration frequency result in energy being coupled from the fundamental vibration frequency to other frequencies through a process known as parametric coupling.

Examples in physics

There are many systems throughout the physical world that can be modeled as anharmonic oscillators in addition to the nonlinear mass-spring system. For example, an atom, which consists of a positively charged nucleus surrounded by a negatively charged electronic cloud, experiences a displacement between the center of mass of the nucleus and the electronic cloud when an electric field is present. The amount of that displacement, called the electric dipole moment, is related linearly to the applied field for small fields, but as the magnitude of the field is increased, the field-dipole moment relationship becomes nonlinear, just as in the mechanical system.

Further examples of anharmonic oscillators include the large-angle pendulum, which exhibits chaotic behavior as a result of its anharmonicity; nonequilibrium semiconductors that possess a large hot carrier population, which exhibit nonlinear behaviors of various types related to the effective mass of the carriers; and ionospheric plasmas, which also exhibit nonlinear behavior based on the anharmonicity of the plasma. In fact, virtually all oscillators become anharmonic when their pump amplitude increases beyond some threshold, and as a result it is necessary to use nonlinear equations of motion to describe their behavior.

Anharmonicity plays a role in lattice and molecular vibrations, in quantum oscillations (see Lim, Kieran F. ; Coleman, William F. (August 2005), "The Effect of Anharmonicity on Diatomic Vibration: A Spreadsheet Simulation", J. Chem. Educ. 82 (8): 1263, Bibcode:2005JChEd..82.1263F, doi:10.1021/ed082p1263.1), and in acoustics. The atoms in a molecule or a solid vibrate about their equilibrium positions. When these vibrations have small amplitudes they can be described by harmonic oscillators. However, when the vibrational amplitudes are large, for example at high temperatures, anharmonicity becomes important. An example of the effects of anharmonicity is the thermal expansion of solids, which is usually studied within the quasi-harmonic approximation. Studying vibrating anharmonic systems using quantum mechanics is a computationally demanding task because anharmonicity not only makes the potential experienced by each oscillator more complicated, but also introduces coupling between the oscillators. It is possible to use first-principles methods such as density-functional theory to map the anharmonic potential experienced by the atoms in both molecules[1] and solids.[2] Accurate anharmonic vibrational energies can then be obtained by solving the anharmonic vibrational equations for the atoms within a mean-field theory. Finally, it is possible to use Møller–Plesset perturbation theory to go beyond the mean-field formalism.

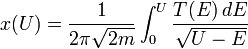

Potential energy from period of oscillations

Let us consider a potential well  .

Assuming that the curve

.

Assuming that the curve  is symmetric about the

is symmetric about the  -axis, the shape of the curve can be implicitly determined from the period

-axis, the shape of the curve can be implicitly determined from the period  of the oscillations of particles with energy

of the oscillations of particles with energy  according to the formula:

according to the formula:

See also

References

- Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1976), Mechanics (3rd ed.), Pergamon Press, ISBN 0-08-021022-8

- Filipponi, A.; Cavicchia, D. R. (2011), Anharmonic dynamics of a mass O-spring oscillator, American Journal of Physics, Volume 79, Issue 7, pp. 730

- ↑ Jung, J. O.;Benny Gerber, R. (1996), "Vibrational wave functions and spectroscopy of (H2O)n, n=2,3,4,5: Vibrational self‐consistent field with correlation corrections", J. Chem. Phys. 105: 10332, Bibcode:1996JChPh.10510332J, doi:10.1063/1.472960

- ↑ Monserrat, B.; Drummond, N.D.; Needs, R.J. (2013), "Anharmonic vibrational properties in periodic systems: energy, electron-phonon coupling, and stress", Phys. Rev. B 87: 144302, arXiv:1303.0745, Bibcode:2013PhRvB..87n4302M, doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.87.144302

External links

- Elmer, Franz-Josef (July 20, 1998), Nonlinear Resonance, University of Basel, retrieved October 28, 2010