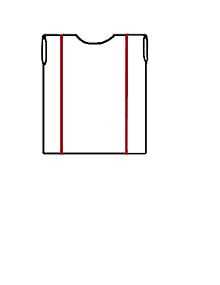

Angusticlavia

An angusticlavia, angusticlavus, or angustus clavus in ancient Rome, was a narrow-strip tunica, or tunic with two narrow and vertical red-purple stripes (clavi). The stripes were worn underneath of the toga, but one was made visible over the right shoulder.[1]

Usage and Significance

The angusticlavia was the tunic associated with the rank and office of the eques, or equestrians, one of the two Roman aristocratic classes. These were military men, often patricians, (patrici) who supplied most of the cavalry in times of war, and in times of peace they were businessmen, often carrying senators' personal businesses. Equestrians wore the angusticlavia under the Trabea, a short toga of distinctive form and color. They also wore equestrian shoes (calcei), and a gold ring (anulus aureus). The tunic's stripes were about an inch wide, which contrasted with the senator's laticlavus marked by the three inch wide stripes.[2][3]

Its two purply slender cloth-bands distinguished members of the Equestrian order from other Roman officers, like the senators who wore the laticlavus, and also from the rest of the citizens who used simpler togas. The color purple became increasingly linked to high class, and then to the Emperor and the empire's magistrates. Thus, the angusticlavia was a clear indication of social status, but one that was recognizable below the senators'.[4][5][6][7]

However, in rare occasions, in times of political or social upheaval, senators in Rome chose to wear the equestrian tunic to make public displays of distress. This practice was part of the semi-egalitarian legacy of the Republic, which at times sprung up to voice the senators', and by association, the people's alarm. In 53 BCE, for example, in the midst of unrestrained civic violence, the consuls put aside their senatorial dress (the laticlavus) and summoned the senate in equestrian attire (the angusticlavia ). And earlier in 58 BCE, when the tribune of the plebs Clodius was pushing Cicero into exile, the senators took on the angusticlavia in public protest.[8] Additionally, as it would be expected of a history that spanned several centuries and involved many regions and people, these dress distinctions were not always evident in Roman societies. Wall paintings and other representations of the Roman past "show all types of men and boys wearing stripes of similar width-- but there were later attempts to enforce or reintroduce the senatorial and equestrian classes."[9]

Etymology

The Latin word angusticlavia, is compounded of angustus ("narrow; small"), and clavus ("nail; stud"). The word clavus, or nail, refers to the stripes, for being long as nails. The term angustus, or narrow, refers to these stripes or ornaments as being slimmer than in the senatorial laticlavus.[10]

See also

- Clothing in ancient Rome

- Laticlavus

References

- ↑ Talbert, Richard (1996). The Senate and Senatorial and Equestrian Posts. In Cambridge Ancient History, Vol X 2nd Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 326. ISBN 0521264308.

- ↑ Goldman, Norma (2001). "Reconstructing Roman Clothing," in title=The World of Roman Costume. Cambridge: Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 221. ISBN 0299138542.

- ↑ Golden, Gregory K (2013). Crisis Management During the Roman Republic: The Role of Political Institutions in Emergencies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 49. ISBN 9781107032859.

- ↑ Johnston, Harold Whetsone (2010). Selected Orations and Letters of Cicero; To Which Is Added the Catiline of Sallust. Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Co.,. p. 51.

- ↑ Grotowsk, Piotr (2010). Arms and Armour of the Warrior Saints: Tradition and Innovation in Byzantine Iconography (843–1261). BRILL. pp. 301 (note 658). ISBN 9004185488.

- ↑ Hart-Davis, Adam (2012). History: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Present Day. Penguin. p. 107. ISBN 9780756698584.

- ↑ Bastús y Carrera, Vicente Joaquín (2008). Tratado de declamación o arte dramático. Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos. p. 253. ISBN 9788424511326.

- ↑ Swan, Peter Michael (2004). The Augustan succession : an historical commentary on Cassius Dio's Roman history, Books 55-56 (9 B.C.-A.D. 14). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 307. ISBN 1423720849.

- ↑ Cleland, Liza; Glenys Davies; and Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2007). Greek and Roman Dress from A to Z. New York: Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 9780415226615.

- ↑ Chambers, Ephraim (1728). Cyclopædia, or, An universal dictionary of arts and sciences : containing the definitions of the terms, and accounts of the things signify'd thereby, in the several arts, both liberal and mechanical, and the several sciences, human and divine : the figures, kinds, properties, productions, preparations, and uses, of things natural and artificial : the rise, progress, and state of things ecclesiastical, civil, military, and commercial : with the several systems, sects, opinions, &c : among philosophers, divines, mathematicians, physicians, antiquaries, criticks, &c : the whole intended as a course of antient and modern learning. London: J. and J. Knapton. p. 99.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ancient Roman fashion. |