Anglo-Saxon weaponry

| This article is part of the series: |

| Anglo-Saxon Society and Culture |

|---|

|

| People |

| Language |

| Material culture |

| Power and organization |

| Religion |

An array of different weapons were created and used in Anglo-Saxon England from the fifth through to the eleventh century CE. Most common were spears, although other missile weapons included bows and arrows, slings, and throwing axes. Weapons designed for hand-to-hand combat included swords, battle axes, and shields. As well as evidently being used by warriors in a military context, weapons also had great symbolic value for the Anglo-Saxons, apparently having strong connotations pertaining to gender and social status.

Weapons were commonly included as grave goods in the inhumation burials of Early Anglo-Saxon England, which were produced from the mid-fifth to the seventh centuries; in the vast majority of cases these were included with men, although in some instances weapons were also deposited with the burials of women and children. During the seventh century, which coincided largely with the Christianisation of the Anglo-Saxons, grave goods ceased to be commonly included in funerary burials. In other examples, weapons were deposited in the ground or water-places in an apparently non-funerary context. However, the establishment of a literate Christian clergy in Anglo-Saxon England allowed for the production of an array of textual sources from the seventh century onward; weapons and the manner in which they were used in warfare are mentioned in a number of these Late Anglo-Saxon sources, most notably Beowulf and The Battle of Maldon.

From the nineteenth century onward, scholarly interest in Anglo-Saxon England led antiquarians and subsequently archaeologists to analyse the material evidence for weaponry from this period, while historians have examined references to weapons in the textual sources. Further, historical re-enactors have created and used replicas of such items.

Evidence

"The early pagan Anglo-Saxons left ample physical evidence of their lives as a result of their practice of burying their dead with grave goods, yet they left no written record; once converted to Christianity and given the opportunity to record their lives with the written word they disdained the pagan practices of their forebears, burying their dead without material possessions. As a consequence, we are repeatedly driven to interpret artefacts from the pagan period on the basis of much later written records".

Although much archaeological evidence for weaponry exists from the Early Anglo-Saxon period due to the widespread inclusion of weapons as grave goods in inhumation burials, scholarly knowledge of warfare itself relies far more on the literary evidence, which was only being produced in the Christian context of the Late Anglo-Saxon period.[2] These literary sources are almost all authored by Christian clergy, and thus do not deal specifically with weapons or their use in warfare; for instance, Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People mentions various battles that had taken place but does not dwell on them.[3] Thus, scholars have often drawn from the literary sources from neighbouring societies, such as those produced by continental Germanic societies like the Franks and Goths, or later Viking sources.[4]

Archaeological evidence for Anglo-Saxon weaponry allows us to both observe the chronological development of weapon styles over time, and to identify regional variations among such styles.[2] Anglo-Saxonist Stephen Pollington asserted that the "Germanic peoples [including the Anglo-Saxons] took great pride in their weapons and lavished much attention on them, in their appearance and in their effectiveness."[5]

In Old English (OE), the primary language of Anglo-Saxon England, multiple different words were often used for the same type of weapon; for instance, in the Beowulf poem, at least six different words are used for spear, thus suggesting that there may have been slight differences of meaning between these terms.[5] In Old English and other Germanic languages which were spoken across much of Northwestern Europe, tribal groups often had names that appear to be based upon those of weapons; for instances, the Angles may have taken their name from the OE angul ("barbed", "hook"), the Franks from the OE franca ("axe?", "spear"), and the Saxons from the OE seax ("knife").[6]

Literary evidence from Later Anglo-Saxon England indicates that only free men were permitted to bear arms.[7] In the law codes of Ine, who was King of Wessex from 688 to 726 CE, there are fines listed for anyone who assists the escape of another's servant by lending them a weapon. The level of fine varied on the weapon, with the fine being greater for a spear rather than a sword.[7]

Weapon types

Spears and javelins

Spears were the most commonly found weapons in Anglo-Saxon England,[8] and were probably the most commonly used weapons in Early Medieval Western Europe more widely.[9] Examples have been found in around 85% of Early Anglo-Saxon graves containing weapons - around 40% of adult male graves from this period.[10] It is known that across many Northern European societies – and probably including Anglo-Saxon England – spears could only be carried by a freeman, with strict punishments found in various law codes for any slaves caught possessing one.[11] In Old English, they were most commonly termed gār and spere, although also appear in textual evidence under more poetic names, such as æsc ("[item made of] ash wood"), ord ("point"), and þrecwudu ("[thing of] wood for harming").[12] When used as a throwing-spear or javelin, they were typically termed daroþ ("dart").[12]

The spears themselves consisted of an iron spearhead mounted on a wooden shaft, often of ash, although other examples have been identified as being of hazel, apple, oak, and maple.[10] There is little evidence how long these spears typically were, although estimates based on grave goods have indicated that they ranged in length from 1.6 to 2.8 metres (5 ft 3 in to 9 ft 3 in).[13] The butt end of the spear was sometimes protected with an iron ferrule, which typically formed a hollow cone which fitted over the shaft; less common were solid cone ferrules.[14] There was great diversity in the size and shapes of the spearheads used in Anglo-Saxon England.[9] These have been categorised into four main-groups, each with its own sub-groups, by J.M. Swanton.[15] Such spearheads were sometimes decorated, with bronze and silver inlay placed on both the blade and the socket; in such instances, a simple ring and dot motif was most common.[16] Occasionally, the ferrule was decorated to match the spearhead.[13] It is possible that the shafts might also have been decorated, perhaps being painted; evidence of such decorated shafts has been found in Danish contexts.[17]

In conflict situations, spears were used both as missiles and as thrusting weapons during hand-to-hand combat.[8] In most cases, it is not possible to identify which of these two purposes a spear was specifically designed for; the exception is with angons, or barbed spears, which were intended for use as missile weapons.[18] Once the spearhead had penetrated a part of an enemy's body, the barb would have made it particularly difficult to remove the weapon, thus increasing the likelihood that the pierced individual would die as a result of the wound.[19] Similarly, if the spearhead had penetrated an enemy's shield, it would have been difficult to remove, thus rendering that shield increasingly heavy, unwieldy, and difficult to use.[20] It is possible that these angons may have developed from the Roman Army's pilum javelins.[18]

"Forðon sceall gar wesan

monig morgenceald mindum bewunden

hæfan on handa"

"Henceforth spear shall be, on many cold morning,

grasped in fist, lifted in hand".

Underwood suggested that when a spear was thrown as a javelin, they its effective range would have been approximately 12 to 15 metres (40 – 50 feet), depending on the javelin's length and weight, and the skill of the individual throwing it.[21] The Battle of Maldon poem describes the use of javelin spears in a fight between earl Byrhtnoth's forces and a Viking group. In this account, one of the Vikings hurled a javelin at Byrhtnoth; although the earl partially deflected it with his shield, he was nevertheless wounded. Byrhtnoth then retaliated by throwing two javelins at the Vikings, piercing one through the neck and another through the chest. The Vikings again threw a javelin, wounding Byrnhoth once more, before one of the earl's warriors pulls that same javelin from the wound, and hurls it back, killing a further Viking. Following this exchange, the two sides drew their swords and engaged in hand-to-hand combat.[21]

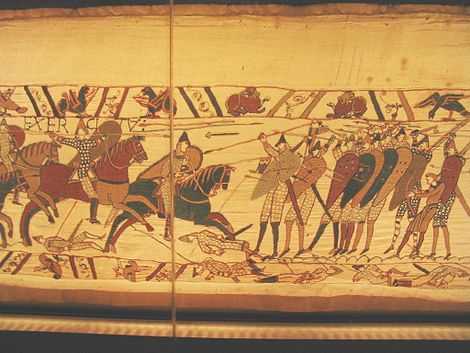

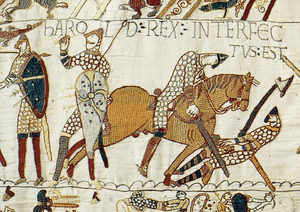

When used in a hand-to-hand combat situation, the spear could be gripped either under-arm or over-arm; examples of the former are depicted on the eighth-century Franks Casket, while the latter is depicted on the eleventh-century Bayeux Tapestry.[22] It is possible that in some instances they were held with two hands at once; there is an eighth-century relief carving from Aberlemno in Scotland depicting a Pictish warrior holding a spear thus, while the Icelandic Late Medieval Grettis saga also describes a spear being used in this manner.[23] However, to do so would have required a warrior relinquishing the protection offered by a shield.[24] To be more effective, ranks of spearmen would stand together to form a shield wall, mutually protecting one another with their shields while pointing their spears at the enemy. Such formations were also known as scyldburh ("shield-fortress"), bordweal ("board-wall"), and wihagan ("war-hedge").[22]

Spears and their uses may also have had symbolic associations. In an account by Bede, the Christian priest Coifi cast a spear into his former pagan temple in order to defile it.[25] In Anglo-Saxon England, the male side of an individual's family was known as "the spear side".[9]

Swords

Pollington describes the sword as "the most symbolically important weapon" of the Anglo-Saxon period,[26] while historian Guy Halsall referred to it as "the most treasured item of early medieval military equipment".[9] In the Old English language, sword was rendered as sweord, although other terms used for such weapons included heoru or heru, bill or bile, and mēce or mǣce.[26] Swords in Anglo-Saxon England comprised two-edged flat, straight blades.[26] The tang of the blade was then covered in a hilt, which consisted of an upper and lower guard, a pommel, and a grip by which the sword itself would have been held.[26] Pommels could be highly decorated in a variety of styles such as the Abingdon Sword or the example found in the Bedale Hoard with unique inlaid gold[27] These Anglo-Saxon blades typically measured between 86 and 94 cm (34 and 37 inches) in length (including tang), and between 4.5 and 5.5 cm in width.[28] However, examples that are larger, reaching up to 100 cm (40 in) in length and 6.5 cm in width, have been discovered.[28]

Rather than being able to melt the iron ore into a complete billet, the furnaces of the period were only able to produce small pieces of iron. These were then forge welded into a single blade, either by being beaten into thin sheets that were then hammered together as a laminated blade or placed together as thin rods and then welded together.[29] Some of these blades were instead constructed using pattern welding. In this, the iron was beaten into strips which were twisted together and then forge welded; this twisting action removed much surface slag which could cause weaknesses in the finished blade.[30] Pattern welding also produced patterns in the finished blade, most commonly according to a herringbone pattern.[31] Such patterns are often referenced in Anglo-Saxon literature, where they are described using such terms as brogenmæl ("weaving marks"), wundenmæl ("winding marks"), grægmæl ("grey mark"), and scirmæl ("brightly patterned").[29] It has thus been suggested that the decoration provided by pattern-welding was important and desired in Anglo-Saxon society.[32] Many blades then also had a fuller, or shallow groove that ran down the length of the blade, reducing its overall weight while not compromising the thickness; this was accomplished by hammering into the blade or by chiselling a section out.[33]

A few swords bore runic inscriptions; for instance a sixth-century example found at Gilton in Kent was inscribed with "Sigimer Made This Sword".[34] It is also apparent from textual sources that swords were sometimes given names, such as the example of Hrunting from Beowulf.[35] In various instances from the sixth century onward, sword-rings were also attached to the upper gard or pommel, many of which were decorated with ornamentation.[36] It is likely that in some instances these served a practical purpose, in attaching a cord to the warrior's wrist – a practice which is attested in later Viking sagas – although in some cases ring knobs were used, which would have rendered this practice impossible; in such cases their inclusion was likely symbolic or ritualistic.[36]

In Old English, the scabbard was known as a scēap ("sheath"), although another term that appears in Anglo-Saxon literature, fætels, could have had the same meaning.[37] The scabbard in which the sword was kept were typically made of wood or leather, while the inside was often lined with fleece or fur, which might have contained grease or oil designed to prevent the sword from rusting.[38] Sometimes the scabbard was further protected from wear and tear by a metal binding known as a frog or locket at its neck, and a chape, based on a simple metal U-shape, at the bottom.[39]

In some instances, a single glass, amber, crystal, or meerschaum bead was attached to the neck of the scabbard by a small strap. Examples can be found for similar sword-beads from Germanic-speaking regions of continental Europe during the Iron Age, and it is likely that they were adopted from the Huns during the fifth century. Such beads may have been amuletic in purpose; in later Icelandic sagas there are references to swords with "healing stones" attached, which may represent the same phenomenon as these Anglo-Saxon beads.[40] The sword and scabbard would then suspended either from a baldric on the shoulder or from a belt on the waist; it is apparent that the former manner was more popular in Early Anglo-Saxon England, with the latter gaining popularity in the Later Anglo-Saxon period, for instance being the only method for carrying a sword depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry.[39]

Both the weight and balance of these swords and descriptions of their use in literary sources like The Battle of Maldon indicate that they were used primarily for heavy cutting and slashing rather than thrusting.[41] A number of corpses discovered from Anglo-Saxon contexts have displayed evidence for having been injured or killed in this manner; at the cemetery of Eccles in Kent, three individuals were identified as having longsword cuts to the left side of the skull.[42]

Knives

In Old English, the term used for knives was seax, and this applied both to single-edged knives that had a blade length of between 8 and 31 cm (3 and 12 in) in length, and the 'long-seax' or single-edged swords which had a blade length that ranged from 54 to 76 cm (21 to 30 in).[43] Archaeologists and historians have sometimes referred to the seax as a scaramax, although this term only appears once in an Early Medieval context; here, it was used by Gregory of Tours in his History of the Franks in reference to a knife used to assassinate the sixth-century Frankish king Sigibert.[44] Early forms of the seax are common in Frankish graves from the fifth century, and it is only later that they appear to have gained in popularity in England.[45] Thus, the seax is primarily associated with Frankish weaponry.[46]

Ownership of the seax indicated the freedom of the owner, and the knife was used primarily for domestic use though could also be used in battle. For some warriors a mid to large sized scramasax took the place of a sword. This knife varies from other knives and swords with its single cutting edge and its length. The Scramasax varied in length from 4–20 in (10–51 cm) with a long handle that was typically wood, though was occasionally iron.[47]

On the basis of the shape of the blade, six main types of Anglo-Saxon knife have been identified.[48] Anglo-Saxon seaxes were commonly constructed using pattern-welding, even in the Late Anglo-Saxon period when pattern-welding had become uncommon among swords.[49] The blades of seaxes were sometimes decorated with incised lines or metal inlays,[50] while a number of examples contain inscriptions bearing the name of the owner or maker.[51] Such weapons were kept in leather sheaths, which were themselves sometimes decorated with embossed designs and silver or bronze fittings.[52] Evidence from graves suggests that the seax and scabbard was then worn across the subject, with the hilt on the right hand side of the body.[53]

It is apparent that most Anglo-Saxons, both women and men, carried knives for use in preparing food and other domestic activities.[54] However, in a conflict situation, such smaller weapons could have been used to kill an already wounded enemy.[54] Alternately, they could have been used in a brawl.[54] Pollington suggested that the longer seaxes might be considered a weapon, while the shorter examples were general-purpose tools.[51] Underwood suggested that the long-seax might have been used for hunting rather than warfare, as evidence highlighting a Frankish pictorial calendar which featured two men killing a boar, one wielding a long-seax.[54]

Axes

In Old English, the axe was referred to as an æsce, from which the Modern English word derives.[55] The Anglo-Saxon hand-axe had a curved outward blade with a long cutting edge, which then narrowed toward the neck.[56] Most examples found in Early Anglo-Saxon graves were fairly small with a straight or only slightly curved blade.[55] Only fragments of the wooden haft survive in a few examples, thus making it difficult to ascertain the typical overall size of the weapon.[57] Such hand-axes primarily served as a tool rather than a weapon, but could have been used as the latter if the need arose.[57]

Various examples of the francisca, or throwing axe, have been found in England.[58] Such weapons can be distinguished from domestic hand axes by the curved shape of their heads.[58] Two main forms of francisca have been identified in England, with one having a convex upper edge, and the other handing an S-shaped upper edge; however, examples that do not clearly fit into either category have also been discovered.[58] Writing in the sixth century CE, the Roman author Procopius described the use of such throwing axes among the Franks of continental Europe, noting that they would be hurled at the enemy prior to engaging in hand-to-hand combat.[59] In that same century, the Frankish chronicler Gregory of Tours described the throwing of an axe at the enemy in his History of the Franks.[59] It is from the Franks that the term francisca originated, however various Medieval authors used the term to refer both to throwing-axes and hand axes.[60] By the seventh century, the throwing axe no longer appeared in the archaeological record and it does not appear in the Frankish Ripuarian Law; this decline in use may indicate the rise of more rightly arrayed formations in battle strategy.[61] It would later be reintroduced into Early Medieval Europe in the late eighth and ninth centuries when it was adopted by the Vikings.[62]

Bow and arrows

Examples of archery equipment from Anglo-Saxon England are rare.[63] Iron arrowheads have been identified in approximately 1% of Early Anglo-Saxon graves, while traces of the wood from the bow save are occasionally identified in the soil of inhumations; in the rare case of the Chessel Down cemetery on the Isle of Wight a bow and arrows were found as grave goods.[25] It is possible that other arrows were fire-hardened or tipped with organic materials such as bone and antler, and thus have not survived in graves.[64] Given that neither bow staves or arrows – both being made of wood – are likely to survive in the soils of England, it is likely that the frequency with which they were included as grave goods was probably higher.[25] In Old English, the bow was known as a boga.[64]

In neighbouring areas of continental Europe with differing soil types, finds of archery equipment are more common; for instance, around forty bow staves and various arrows were uncovered at Nydam Mose in Denmark and dated to the third or fourth century CE, while similar equipment was discovered at Thorsberg moor in Germany.[65] From such continental evidence, it has been asserted that the form of bow common to Early Medieval Northwestern Europe was the long bow with a stave constructed from a single piece of wood. The string would then have been made of hair or animal gut.[66] Underwood suggested that the maximum range of an Anglo-Saxon bow would have been around 150 to 200 metres (500 to 650 feet), although noted that beyond a range of 100 to 120 metres (325 to 400 feet) the power of the arrow would have been much diminished, meaning that it would only be able to cause relatively minor wounds.[67]

Anglo-Saxon arrowheads have been divided into three main types.[68] The first are the leaf-shaped arrowheads, which typically contained a socket which allowed the head to be attached to the wooden shaft.[68] The second are triangular of square-sectioned bodkins.[68] The third are barbed arrowheads which typically contained a simple tang that was either driven into the end of the shaft or tied on to it.[68] Underwood suggested that the leaf-shaped and barbed arrowheads developed from styles of arrow that had been used for hunting.[68] Conversely, he suggested that bodkins were designed for use in battle against armoured opponents, because the long tapering point would pass through the links of a chainmail short or puncture the iron plate of a helmet if fired at close range.[69] The size of the arrowheads varied from 5.5 cm (2 inches) to 15.5 cm (6 inches),[68] and thus it is not always possible to distinguish between the larger arrow heads and the smaller javelin heads.[70]

Despite their infrequent appearance in the burial record, bows appear more widely in Anglo-Saxon art and literature.[71] On the eighth-century Northumbrian Franks Casket, a single archer is depicted defending a hall from a group of warriors.[72] There are 29 archers depicted on the eleventh-century Bayeux Tapestry, 23 of whom appear in the border and 6 in the main scene; however, only one of these is explicitly identified as being an Anglo-Saxon, the rest being Norman.[73] Underwood suggested that most men in Anglo-Saxon England would have known how to use a bow for the purposes of hunting,[58] with Pollington suggesting that it was primarily an item used for hunting rather than for warfare.[74]

Sling

There is limited evidence for the use of slings as weapons in Anglo-Saxon England, with these items instead normally being depicted as hunting items.[75] In Old English, the sling was known as a liðere or liðera, and sometimes as a stæfliðere ("staff-pouch").[74] In the Vita Sancti Wilfrithi, an eighth-century hagiography of the bishop and later saint, Wilfrid, reference is made to an event in which the saint and his companions were attacked by pagans when their ship ran aground; one of the saint's companions fired a stone from a sling which killed the pagan priest.[60] An image of a man hunting birds using a sling appears on the lower margin of the Bayeux Tapestry.[76] Underwood has suggested that the sling may not have been used in war, and that its use as a weapon – as in the account of Saint Wilfred – was only as a last resort.[76] Further, he suggested that the scene with the sling in Wilfrid's hagiography may not constitute an accurate account of the event but that it may instead reflect the writer's desire to draw Biblical parallels.[76]

Armour and defensive equipment

Shield

The shield is the second most common item of wargear found from Anglo-Saxon England.[77] Examples have been found from almost a quarter of male graves from the Early Anglo-Saxon period.[77] In Old English, the shield was termed a bord, rand, scyld, and lind ("linden-wood").[78] These shields consisted of a circular wooden board that had been constructed from planks of solid wood which had been glued together, with an iron boss then affixed to the centre. The shield was then often covered in leather, which served to help hold the planks together, and decorated with bronze or iron fittings and studs.[79] Textual and pictoral depictions of shields suggest that in some cases they may have had a convex shape, although this has yet to be corroborated archaeologically, with known archaeological examples suggesting that they were non-convex.[80] Although there is no archaeological evidence that shields in Anglo-Saxon England were painted, contemporary examples of painted shields have been found in Denmark, while in Beowulf shields are described as "bright" and "yellow", suggesting that this might have been the case in some instances.[81]

Although in Old English poetry the shields are always referred to as being made out of lime (linden-wood), archaeological discoveries instead indicate that this wood was used rarely, with alder, willow, and poplar being most common, and maple, birch, ash, and oak also being found.[82] The size of the shields varied widely, from between 0.3 to 0.92 m (1 to 3 ft) in diameter, although the majority fitted within a range of 0.46 to 0.66 m (1 ft 6 in to 2 ft 2 in) in diameter.[83] Similarly, the thickness of the board also appears to have varied, from between 5 mm and 13 mm, although the majority were in the range between 6 mm and 8 mm in width.[81]

The types of boss found in Anglo-Saxon England have been divided into two main types on the basis of how they were manufactured.[84] The most common form is known as the carinated boss; originating in continental European designs, this was found in England from the fifth until at least the mid-seventh century. The precise manner of manufacture remains elusive.[84] The second type was the tall cone boss, which became popular in the seventh century and which was made from a sheet or multiple sheets of iron, with welds that run from the rim to the apex of the boss.[85] The boss was then attached to the wooden shield with iron or bronze rivets; usually four or five were used, although in some cases as many as twelve were used.[85] Behind the boss, the board was cut away and an iron grip fitted across the opening, with which the shield was held.[86] Most of these grips were a strap 10 to 16 cm (4 to 6 in) in length, with the sides being either straight or gently curved; in a few cases, flanges are evident, which would have enclosed a wooden handle.[87]

The shield would have been the only piece of defensive equipment available to most Anglo-Saxon warriors.[88] Pollington suggested that it was also "perhaps the most culturally significant piece of defensive equipment" in Anglo-Saxon England, because the shield-wall would represent a symbolic demarcation of "us" and "them" on the battlefield.[78] Smaller shields would have been lighter to carry and easier to manoeuver, and thus were better suited to small skirmishes and single combat.[88] Conversely, the larger shields would have been of greater use in pitched battles, when they provided greater protection from projectile weapons and were necessary to construct a shield wall against the enemy.[88]

In Old English, mailcoats worn as a form of body armour were referred to as byrne and hlenca.[89] The wearing of mail is repeatedly referred to in Late Anglo-Saxon textual sources, however it appears rarely in an archaeological context.[90] The only known surviving example of a complete mail shirt from this period was discovered during the excavation of the cemetery of Sutton Hoo in Suffolk, although even here it is badly corroded.[91] This lack of archaeological evidence may therefore be due to general corrosion rather than an actual lack of mail being deposited in the archaeologial record.[90] A full, well-preserved mail shirt akin to those that were likely used in Anglo-Saxon England was found in Vimose, Denmark, and dated to the fourth or fifth century.[90]

The Sutton Hoo mail shirt was composed of iron rings which were 8 mm (0.31 in) in diameter, some of which were closed with copper rivets, suggesting that the mail was probably created using alternate rows of riveted and forged or welded rings.[91] It probably reached hip length when worn.[90] To produce such an item, a thin metal strand of wire would have to have been produced, either by swaging (hammering a heated billet into grooves of decreasing size) or drawing (pulling the heated metal through channels of decreasing size).[92] At this point, the wire would then have been coiled tightly around a circular rod approximately 10 mm (0.39 in) in diameter. Individual circuits would then have been chiselled off the rod, before being reheated and then annealed; these individual links would then be joined and closed using welding and riveting.[93] Once the mailcoat had been constructed in this manner, it would have been case hardened by being packed in charcoal and reheated to enable some of the carbon to transfer to the metal's outer face.[93]

Shirts of mail would have offered much protection during conflict, lessening the impact of any blow received, and thus would have given a significant advantage to those wearing it against opponents who were not.[94] They were particularly effective against cutting blows from a sword or axe, because the impact of the blow was absorbed and distributed across the many mail links; they would be less effective at preventing a direct hit from a spearpoint, the concentrated impact of which could break a few links and impale into the body, sometimes forcing links into the body with it.[95] Further, they added much weight to the warrior, making mobility more difficult, disadvantaging the wearer greatly during skirmishing situations or on occasions when the battle line moved quickly.[96] They also rusted easily, and thus had to be cared for.[97]

Helmets

In Old English, the helmet was referred to as a helm.[98] Available evidence suggests that helmets were not common at any point in the Anglo-Saxon period,[99] although their usage might have increased by the eleventh century; a 1008 edict of Cnut the Great stipulated that those presenting themselves for active service had to have a helmet.[98] It is possible that many of these were made from boiled leather, and hence do not survive archaeologically.[98] Four largely complete examples of Anglo-Saxon helmets have been discovered, although fragments of what could be others have also been unearthed from archaeological contexts.[100] All of these examples show significant differences in their construction and ornamentation.[96] Helmets are further mentioned in Late Anglo-Saxon texts, such as Beowulf.[101] In conflict situations, helmets would have been useful in defending the head from enemy blows.[101]

The earliest dated example was that found at Sutton Hoo, an elite burial dated to the seventh century; the helmet itself however could be older, and may date to the first quarter of the sixth century.[102] The helmet's bowl is composed of a single piece of metal, to which cheek-pieces, a metal neck-guard, and a face-mask, were attached.[103] The helmet is elaborately decorated, with two dragons designed on it, and embossed foil plates of tinned bronze making out at least five designs.[104] The artistic depictions on the helmet have similar parallels elsewhere in England and also in Germany and Scandinavia; the helmet itself is similar to examples found at Vendel and Valsgärde in Sweden, resulting in some suggestions that it was made in Sweden or by a Swedish craftsman active in England.[105] Possible fragments of helmet crests akin to that on the Sutton Hoo example have been discovered from Rempstone in Nottinghamshire and Icklingham in Suffolk, suggesting the possibility that helmets such as these might have been more common that the evidence suggests.[106]

The Benty Grange Helmet was discovered at Benty Grange in Derbyshire and has been dated to the mid-seventh century.[107] Constructed from seven iron bands, it is topped with the bronze figure of a boar, which has been decorated with garnet eyes in beaded gold mounts and gilded inlayed tusks and ears.[108] Thomas Bateman, who had discovered the Benty Grange Helmet in 1848, also noted finding metal bands that he thought came from a second helmet in a second burial mound about a mile away; this artefact has not been preserved, and thus it has not been positively identified as such.[109] A similar bronze boar has been found in a female grave from Guilden Morden in Cambridgeshire; while it appears to have come from the crest of the helmet, there were no other traces of a helmet, suggesting that it might have been detached prior to being included as a grave good.[110] The Pioneer Helmet, found in Wollaston in Northamptonshire, also has a boar crest, although this is made of iron.[111]

Dated to the mid-to-late eighth century, the Coppergate Helmet was found from a Viking settlement in York, although identified as Anglian in origin.[110] It comprises a bowl made of iron plates with added hinged iron cheek-pieces and a mail curtain at the back of the neck.[112] The nasal plate is decorated with an animal interlace design, which extend over the eyebrow area of the helmet, terminating in small canine head designs.[110] On the two crests of the bowl are Christian inscriptions written in Latin praising the Trinity.[113]

Manufacture of weapons

Underwood suggested that simple weapons, such as spearheads and knives, could have been produced by any smith.[114] Conversely, he suggested that many other weapons, and in particular swords, would have required specialist skills to manufacture.[114] In some cases, smith's tools have been archaeologically identified; for instance, a set of seventh-century tools including an anvil, hammers, tongs, a file, shears, and punches were discovered in a grave at Tattershall Thorpe in Lincolnshire.[114]

Artistic elements of Anglo-Saxon weapons show many similarities with those in other parts of northern Europe and Scandinavia, testifying to continual contact between these regions in the period.[115] While some developments were imported to England from elsewhere, it is clear that English developments also influenced the continent.[115] For instance, the sword ring appears to have first developed in mid-sixth century Kent before being exported elsewhere, becoming widespread across the continent by the seventh century, in both linguistically-Germanic areas and Finland and Lombardic Italy.[116]

Weapon deposition

Inhumation burials

According to historian Guy Halsall, the "deposition of grave-goods was a ritual act, wherein weaponry could symbolise age, ethnicity or rank; at various times and places a token weapon might be used to illustrate such concepts."[117]

Non-funerary depositions

Many Late Anglo-Saxon swords have been found in riverside sites.[118] Pollington suggested that this was either due to a return to prehistoric practices of "deposition in sacred waters" or a reflection that battles were increasingly being fought at fords, something that is attested to in contemporary textual sources such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.[118]

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Underwood 1999, pp. 15, 18.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Underwood 1999, p. 13.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 15.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Pollington 2001, p. 104.

- ↑ Pollington 2001, p. 108.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Underwood 1999, p. 114.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Underwood 1999, p. 23.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Halsall 2003, p. 164.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Underwood 1999, p. 39.

- ↑ Pollington 2001, p. 128.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Pollington 2001, p. 129.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Underwood 1999, p. 44.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, pp. 39, 43–44; Pollington 2001, p. 131.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, pp. 39–40; Pollington 2001, p. 130.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 43.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 44; Pollington 2001, p. 129.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Underwood 1999, p. 24; Pollington 2001, p. 130; Halsall 2003, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 24; Pollington 2001, p. 130.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 24.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Underwood 1999, p. 25.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Underwood 1999, p. 46.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Pollington 2001, p. 137.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Underwood 1999, p. 26.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Pollington 2001, p. 110.

- ↑ "Beauty of hoard is revealed as rare Viking treasures displayed". Yorkshire Post. 2014-12-12. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Underwood 1999, p. 47.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Underwood 1999, p. 48.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 48; Pollington 2001, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 48; Pollington 2001, p. 119.

- ↑ Pollington 2001, p. 119.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 48; Pollington 2001, p. 110.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 54; Pollington 2001, p. 122.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 54.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Underwood 1999, p. 56; Pollington 2001, p. 114.

- ↑ Pollington 2001, p. 118.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 58; Pollington 2001, p. 117.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Underwood 1999, p. 59; Pollington 2001, p. 117.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 61; Pollington 2001, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 62; Pollington 2001, p. 123.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 63.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 68.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 68; Pollington 2001, p. 165.

- ↑ Pollington 2001, p. 165.

- ↑ Brown, Katherine (1989). "The Morgan Scramasax". Metropolitan Museum Journal 24: 71–3. doi:10.2307/1512870.

- ↑ Powell, John (2010). Weapons and Warfare, Rev. Ed. Salem Press. ISBN 978-1-58765-594-4.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Pollington 2001, p. 166.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 70; Pollington 2001, p. 167.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Pollington 2001, p. 167.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 70; Pollington 2001, pp. 167–168.

- ↑ Pollington 2001, p. 168.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 Underwood 1999, p. 71.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Pollington 2001, p. 138.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 72.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Underwood 1999, p. 73.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 Underwood 1999, p. 35.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Underwood 1999, pp. 35, 37.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Underwood 1999, p. 37.

- ↑ Halsall 2003, p. 165.

- ↑ Halsall 2003, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 26; Halsall 2003, p. 166.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Pollington 2001, p. 170.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, pp. 26–28; Pollington 2001, p. 170.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 28.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, pp. 32, 34.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 68.3 68.4 68.5 Underwood 1999, p. 29.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 31.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 29; Pollington 2001, p. 171.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 32.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 32; Pollington 2001, p. 173.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 32; Pollington 2001, pp. 173–174.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Pollington 2001, p. 175.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 37; Pollington 2001, p. 175.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 Underwood 1999, p. 38.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Underwood 1999, p. 77.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Pollington 2001, p. 141.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, pp. 77, 79; Pollington 2001, pp. 144, 148–149.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 79; Pollington 2001, p. 148.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Underwood 1999, p. 79.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 77; Pollington 2001, p. 148.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 79; Pollington 2001, p. 147.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Underwood 1999, p. 81.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Underwood 1999, p. 82.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 77; Pollington 2001, p. 146.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 84.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 Underwood 1999, p. 89.

- ↑ Pollington 2001, p. 151.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 90.3 Underwood 1999, p. 91.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Underwood 1999, p. 91; Pollington 2001, p. 152.

- ↑ Pollington 2001, p. 153.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Pollington 2001, p. 154.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 93.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Underwood 1999, p. 94.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 94; Pollington 2001, p. 154.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 98.2 Pollington 2001, p. 155.

- ↑ Pollington 2001, p. 103.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 94; Pollington 2001, p. 155.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Underwood 1999, p. 105.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 95; Pollington 2001, p. 156.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 95; Pollington 2001, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 98; Pollington 2001, p. 156.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 98.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 100; Pollington 2001, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 100; Pollington 2001, p. 160.

- ↑ Pollington 2001, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 110.2 Underwood 1999, p. 102.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, pp. 103–104; Pollington 2001, p. 162.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 102; Pollington 2001, pp. 163–164.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 103; Pollington 2001, p. 164.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 114.2 Underwood 1999, p. 115.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 Underwood 1999, p. 145.

- ↑ Underwood 1999, p. 145; Pollington 2001, p. 114.

- ↑ Halsall 2003, p. 163.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 Pollington 2001, p. 116.

Bibliography

- Bone, Peter (1989). Development of Anglo-Saxon Swords from the Fifth to the Eleventh Century. Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology Monograph.

- Brady, Caroline (1979). "Weapons in Beowulf: Analysis of the Nominal Compounds and an Evaluation of the Poet's Use of Them". Anglo-Saxon England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 8: 79–141. doi:10.1017/s0263675100003045.

- Brooks, N. (1991). "Weapons and Armour". The Battle of Maldon, AD 991. Donald Scragg (ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 208–219.

- Cameron, Esther (2000). Sheaths and Scabbards in Anglo-Saxon England, AD 400–1000. British Archaeological Reports, British Series 301. Oxbow.

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1994) [1962]. The Sword in Anglo-Saxon England: Its Archaeology and Literature. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851157160.

- Dickinson, Tanya; Härke, Heinrich (1993). Early Anglo-Saxon Shields. London: Society of Antiquaries.

- Halsall, Guy (2003). Warfare and Society in the Barbarian West, 450–900. London and New York: Routledge.

- Pollington, Stephen (2001). The English Warrior: From Earliest Times till 1066 (second ed.). Hockwold-cum-Wilton: Anglo-Saxon Books. ISBN 1 898281 42 4.

- Reynolds, Andrew; Semple, Sarah (2011). "Anglo-Saxon Non-Funerary Weapon Depositions". Studies in Early Anglo-Saxon Art and Archaeology: Papers in Honour of Martin G. Welch. Stuart Brookes, Sue Harrington, and Andrew Reynolds (eds.). Archaeopress. pp. 40–48. ISBN 9781407307510.

- Swanton, M.J. (1973). The Spearheads of the Anglo-Saxon Settlements. Leeds: Royal Archaeological Institute.

- Underwood, Richard (1999). Anglo-Saxon Weapons and Warfare. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 07524 1412 7.