Andromède

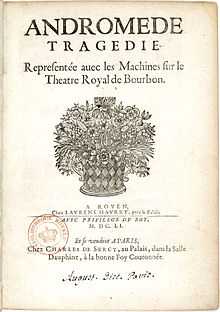

Andromède (Andromeda) is a French verse play in a prologue and five acts by Pierre Corneille, first performed c. 1 February 1650 by the Troupe Royale de l'Hôtel de Bourgogne at the Théâtre Royal de Bourbon in Paris.[1] The story is taken from Books IV and V of Ovid's Metamorphoses and concerns the transformation of Perseus and Andromeda.[2]

Background

The play was commissioned by Cardinal Mazarin in 1648 but wasn't finished until 1650. Corneille dedicated the piece to an unknown woman designated by four uppercase M's.[3] According to Abel Lefranc, the M's represent Madame de Motteville, the confidante of Anne of Austria.[4]

Plot

- Prologue: Respects to the King

- Act I: Venus predicts the marriage of Andromeda while a final victim will be chosen for the monster Cetus.

- Act II: Andromeda is designated as the victim.

- Act III: Perseus kills the monster; the Nereids promise to avenge it.

- Act IV: Phineus wants to kill Perseus and gets the aid of Juno.

- Act V: Perseus astounds Phineus; all the characters ascend to heaven to become gods.

Characters

|

Gods in the Machines[5]

|

Mortals

|

Premiere

The premiere production incorporated spectacular scenery, set changes, and special effects, designed by Giacomo Torelli. Many of the sets were recycled from Torelli's production of Luigi Rossi's opera Orfeo, performed at the Palais-Royal in 1647. A series of six engravings created by François Chauveau depicted scenes from the prologue and five acts of Andromède, and these were published in Rouen in 1651, both separately and with the second edition of the play.[6] Charles d'Assoucy composed incidental music, which included airs, duets, and choruses, that primarily functioned to cover up the noise of the stage machinery during scene changes and special effects, such as the descent of Jupiter, Juno and Neptune in the final act. Corneille did not look too favorably on the music: "I have employed music only to satisfy the ear while the eyes are looking at the machines, but I have been careful to have nothing sung that is essential to the understanding of the play because the words are generally badly understood in music."[7] Most of the music has been lost, except for two choruses published in Airs à quatre parties (Robert Ballard, Paris, 1653).[8]

Engravings by Chauveau

-

Prologue: Melpomène, flying in the sky, and the Sun in his "luminously bright chariot"

-

Act 1: Vénus in her "glory"

-

Act 3: Persée rescues the rock-bound Andromède from the Sea Monster

Later productions

- 1655: Andromède was revived at the Théâtre du Marais with machinery and sets designed by Denis Buffequin.[9]

- 1682: A revival by the Comédie-Française at the Théâtre Guénégaud included a live horse flying through the air. According to the Parfaict brothers, the horse was persuaded to portray a "warlike ardor" by a severe fast, and "when he appeared a theatre employee was in the wings sifting oats. The horse overcome by hunger, neighed, stamped his feet and thus acted exactly as it was wished he should. [...] This acting on the part of the horse greatly contributed to the success the tragedy enjoyed at that time."[10]

References

Notes

- ↑ Powell 2000, p. 25; Garreau 1984, p. 554. Regarding the date of the premiere, Powell says: "The Troupe Royale of the Hôtel Bourgogne finally produced Andromède during 1–22 February 1650", citing G. Mongrédien, "Sur quelques représentations d'Andromède", XVIIe siècle, vol. 116 (1977), pp. 59–61, ISSN 0012-4273. Garreau merely says "early 1650". The Notice de spectacle (Andromède) of the BnF gives 26 January 1650; Jean Claude Brenac's Le magazine de l'opéra baroque ("Andromède") says: "représentée en 1650 (pendant la Fronde)".

- ↑ Corneille 1651a, "Argument"; 1651b, "Argument".

- ↑ Corneille 1651a, "Epistre"; 1651b, "Epistre".

- ↑ Abel Lefranc, "Le mythe d'Andromède dans la tragèdie de Corneille", Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, vol. 72 (1928), no. 3, pp. 246–248. ISSN 0065-0536.

- ↑ The list of characters is from Corneille 1651b, "Acteurs".

- ↑ Powell 2000, p. 25; John 1998; Coeyman 1998, p. 63; Howarth 1997, pp. 205–209.

- ↑ Quoted and translated by Isherwood 1973, p. 126.

- ↑ Powell 2000, p. 25 note 63; Margaret M. McGowan, "Dassoucy, Charles” in Grove Music Online.

- ↑ Powell 2000, p. 26; Howarth 1997, p. 210.

- ↑ Howarth 1997, pp. 355, 357.

Sources

- Coeyman, Barbara (1998). "Opera and Ballet in Seventeenth-Century French Theatres: Case Studies of the Salle des Machines and the Palais Royal Theater" in Radice 1998, pp. 37–71.

- Corneille, Pierre (1651a). Andromède, 1st edition. Rouen: Laurens Maurry. Copy at Gallica.

- Corneille, Pierre (1651b). Andromède, 2nd edition with engravings. Rouen: Laurens Maurry. Copy at Gallica.

- Garreau, Joseph E. (1984). "Corneille, Pierre", vol. 1, pp. 545–554, in McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of World Drama, Stanley Hochman, editor in chief. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780070791695.

- Howarth, William D., editor (1997). French Theatre in the Neo-classical Era, 1550–1789. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521100878.

- Isherwood, Robert M. (1973). Music in the Service of the King. France in the Seventeenth Century. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801407345.

- John, Richard (1998). "Torelli, Giacomo" in Turner 1998, vol. 31, pp. 165–166.

- Powell, John S. (2000). Music and Theatre in France 1600–1680. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198165996.

- Radice, Mark A., editor (1998). Opera in Context: Essays on Historical Staging from the Late Renaissance to the Time of Puccini. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 9781574670325.

- Turner, Jane, editor (1998). The Dictionary of Art, reprinted with minor corrections, 34 volumes. New York: Grove. ISBN 9781884446009.

| ||||||||