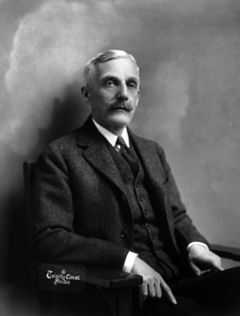

Andrew W. Mellon

| Andrew W. Mellon | |

|---|---|

| |

| 11th United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom | |

| In office February 5, 1932 – March 20, 1933 | |

| President | Herbert Hoover |

| Preceded by | Charles G. Dawes |

| Succeeded by | Robert Worth Bingham |

| 49th United States Secretary of the Treasury | |

| In office March 9, 1921 – February 12, 1932 | |

| President | Warren G. Harding Calvin Coolidge Herbert Hoover |

| Preceded by | David F. Houston |

| Succeeded by | Ogden L. Mills |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Andrew William Mellon March 24, 1855 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | August 26, 1937 (aged 82) Southampton, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Trinity Episcopal Church Cemetery Upperville Fauquier County, Virginia |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Nora McMullen (1878–1973 m. 1900–1912 divorced) |

| Relations | Richard B. Mellon (1858–1933) (brother) |

| Children | Paul Mellon (1907–1999) Ailsa Mellon Bruce (1901–1969) |

| Parents | Thomas Alexander Mellon (1813–1908) Sarah Jane Negley (1817–1909) |

| Alma mater | Western University of Pennsylvania (University of Pittsburgh) |

| Profession | Banker, politician |

| Religion | Episcopalian |

Andrew William Mellon (/ˈmɛlən/; March 24, 1855 – August 26, 1937) was an American banker, businessman, industrialist, philanthropist, art collector, United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom and United States Secretary of the Treasury from March 4, 1921 to February 12, 1932, from the wealthy Mellon family of Pennsylvania. He and his brother Richard Beatty Mellon and (independently) Andrew Carnegie founded two institutes of higher education that would eventually merge to form Carnegie Mellon University.

Early life

Mellon was born in Pittsburgh on March 24, 1855. His name is listed on the 1860 Census as "William A. Mellon." His father was Thomas Mellon, a banker and judge who was a Scots-Irish immigrant from County Tyrone, Ireland; his mother was Sarah Jane Negley Mellon. He had three older brothers, Thomas A., James R. and Samuel, and he also had a younger brother named Richard B. Mellon. He was educated at the Western University of Pennsylvania (now the University of Pittsburgh) and left before graduating.[1]

Financial prodigy

Mellon demonstrated financial ability early. In 1872 his father set him up in a lumber and coal business, which he soon turned into a profitable enterprise. He joined his father's banking firm, T. Mellon & Sons, in 1880 and two years later had ownership of the bank transferred to him. In 1889, Mellon helped organize the Union Trust Company and Union Savings Bank of Pittsburgh. He also branched into industrial activities: oil, steel, shipbuilding, and construction.

Areas where Mellon's backing created giant enterprises included aluminum, industrial abrasives ("carborundum"), and coke. Mellon financed Charles Martin Hall, whose refinery grew into the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa). He became the partner of Edward Goodrich Acheson in manufacturing silicon carbide, a revolutionary abrasive, in the Carborundum Company. He created an entire industry through his help to Heinrich Koppers, inventor of coke ovens which transformed industrial waste into usable products such as coal-gas, coal-tar, and sulfur. He also became an early investor in the New York Shipbuilding Corporation.[2]

Mellon was one of the wealthiest people in the United States, the third-highest income-tax payer in the mid-1920s, behind John D. Rockefeller and Henry Ford.[1] While he served as Secretary of the U.S. Treasury Department his wealth peaked at around $300–$400 million in 1929–1930.

Mellon was a member of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club (whose earthen dam failed in May, 1889, causing the Johnstown Flood), and he belonged to the Duquesne Club in Pittsburgh. Along with his closest friends Henry Clay Frick and Philander Knox (also South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club members), Mellon served as a director of the Pittsburgh National Bank of Commerce.[3]

Career

Secretary of the Treasury

Andrew Mellon was appointed Secretary of the Treasury by new President Warren G. Harding in 1921. He served for 10 years and 11 months; the third-longest tenure of a Secretary of the Treasury. His service continued through the Coolidge and Hoover administrations. Along with Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson and Secretary of Labor James J. Davis, he is one of only three Cabinet members to serve in the same post under three consecutive Presidents.

Harding, in his inaugural address on March 4, 1921, called for a prompt and thorough revision of the tax system, an emergency tariff act, readjustment of war taxes, and creation of a federal budget system. These were policies Mellon wholeheartedly subscribed to, and his long experience as a banker qualified him to set about implementing these programs immediately. As a conservative Republican and a financier, Mellon was irritated by the manner in which the government's budget was maintained, with expenses due now and rising rapidly, with the failure of income or revenues to keep pace with those expense increases, and with the lack of savings.

In 1926 Mellon was involved in drafting the Mellon-Berenger Agreement to set the amount of French debts to the United States arising from loans during World War I and define the repayment schedule. The agreement was named after him and the French Ambassador Henry Bérenger who signed the agreement in April 1926 subject to ratification by the French parliament. The agreement greatly reduced the amount owing, but was felt to be as much as the French would be able to pay.[4]

Mellon was a key negotiator on Germany's war debt, even traveling to Paris in the summer of 1931 to conduct talks on it. He responded to fears that Germany might strike out against its debt plight with: "everything will work out all right".[5]

Mellon plan

Mellon came into office with a goal of reducing the huge federal debt from World War I. To do this, he needed to increase federal receipts and decrease federal spending. He believed that if the tax rates were too high, then the people would try to avoid paying them. Mellon also believed that by reducing taxes the federal government could actually increase receipts, an idea he termed "scientific taxation." He observed that as tax rates had increased during the first part of the 20th century, investors moved to avoid the highest rates—by choosing tax-free municipal bonds, for instance. As Mellon wrote in 1924:[6]

The history of taxation shows that taxes which are inherently excessive are not paid. The high rates inevitably put pressure upon the taxpayer to withdraw his capital from productive business.

If the rates were set more reasonably, taxpayers would have less incentive to avoid paying. His theory was that by lowering the tax rates across the board, he could increase the overall tax revenue. This is similar to the Laffer curve.

Andrew Mellon's plan had four main points:

- Cut the top income tax rate from 77 to 24 percent – predicting that large fortunes would be put back into the economy.

- Cut taxes on low incomes from 4 to 1/2 percent – tax policy "must lessen, so far as possible, the burden of taxation on those least able to bear it."

- Reduce the Federal Estate tax – large income taxes tempted the wealthy to shift their fortunes into tax-exempt shelters.

- Efficiency in government – lower tax rates meant few tax returns to process by few government workers; cutting the actual size of paper bills to fit into wallets saved expenses in paper and ink.

Mellon believed that the income tax should remain progressive, but with lower rates than those enacted during World War I. He thought that the top income earners would willingly pay their taxes only if rates were 25% or lower. Mellon proposed tax rate cuts, which Congress enacted in the Revenue Acts of 1921, 1924, and 1926. The top marginal tax rate was cut from 73% to 58% in 1922, 50% in 1923, 46% in 1924, 25% in 1925, and 24% in 1929. Rates in lower brackets were also cut substantially, relieving burdens on the middle-class, working-class, and poor households.

By 1926 65% of the income tax revenue came from incomes $300,000 and higher, when five years prior, less than 20% did. During this same period, the overall tax burden on those that earned less than $10,000 dropped from $155 million to $32.5 million.[7]

Mellon also championed preferential treatment for "earned" income relative to "unearned" income. As he argued in his 1924 book, Taxation: The People's Business[8]

The fairness of taxing more lightly incomes from wages, salaries and professional services than the incomes from business or from investments is beyond question. In the first case, the income is uncertain and limited in duration; sickness or death destroys it and old age diminishes it. In the other, the source of the income continues; the income may be disposed of during a man's life and it descends to his heirs.Surely we can afford to make a distinction between the people whose only capital is their mental and physical energy, and the people whose income is derived from investments. Such a distinction would mean much to millions of American workers and would be an added inspiration to the man who must provide a competence during his few productive years to care for himself and his family when his earning capacity is at an end.[9]

Mellon's policies helped reduce the overall public debt (the national debt skyrocketed from $1.5 billion in 1916 to $24 billion in 1919 because of World War I obligations) from $33 billion in 1919 to about $16 billion in 1929,[10] but then the Depression caused it to rise again because of reduced revenue and increasing spending. The top tax rate went to 80% by 1935 and the federal government increased excise taxes in an attempt to make up for the lost revenue.[7]

Mellon's tax plan also had social ramifications on society and the cultural development of the American people. The tax reforms exemplified the transition from a 19th-century rural society to the industrial capitalist power the country had become into the 1920s. Populists and rebellious republicans representing constituencies from the south, west, and mid-west, all opposed Mellon's tax reforms because they were resistant to trend toward an urban society.[11] Since the tax system is a legal system bound by the law, the economic ramifications of its implementation transformed society's interaction and contribution to the overall economy. Mellon's tax plan replaced the United States main source of revenue from national tariffs and general state property taxes to a progressive income tax system. Combined with an pro-big business dominant political ideology and the reformation of the federal government's revenue stream, Mellon's tax cut on the wealthy and big corporations encouraged greater investment by wealthy individuals and big companies.[11] He believed tax cut's effectiveness on encouraging investment spending was more beneficial to the economy than placing a higher tax burden on the rich. As Mellon had postulated, reducing tax rates on the wealthy class encouraged wealthy individuals to invest more into projects that contributed to the infrastructural development of cities and neighborhoods within. In New York City during the 1920s, the social ramifications were realized as many neighborhoods sprang up and were settled by people of different ethnicities and income that has given the city the cultural diversity it is known for today.[12]

Great Depression

Mellon became unpopular with the onset of the Great Depression. Herbert Hoover, in memoirs published decades later, wrote that Mellon advised him as President to "liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate farmers, liquidate real estate... it will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up from less competent people." Hoover claimed credit for disregarding this advice and intervening in the market, though with little success.[13] There is no corroboration that Mellon ever said such a thing, however, and the claim that he did is inconsistent with his published speeches, which supported anti-recessionary measures by the Federal Reserve. As Treasury Secretary, Mellon was an ex-officio member of the Federal Reserve Board. There successfully urged the Fed to cut its discount rate after the stock market crash in October 1929, and supported subsequent rate cuts. [14] In November 1929, he recommended a cut of 1 percentage point in personal and corporate income tax rates. He supported Hoover's proposal to increase federal construction spending as an antirecession measure. [1]

In 1929–31, Mellon spent much of the time overseas, negotiating for repayment of European war debts from World War I. In 1928 Mellon issued a denial to allegations made by a speaker for the Democratic Party in North Carolina that he held an interest in a liquor distillery, and that he was the largest distiller in the world prior to Prohibition. In a letter written to the Republican executive committee of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, Mellon admits having stock in a distillery, but that he had disposed of all interest in the company prior to becoming Secretary of the Treasury.[15]

Impeachment proceedings

In January 1932, 25,000 jobless men from Pennsylvania (Cox's Army) marched to Washington to petition Congress and Hoover to start a job program. Hoover, fearing Communist agitation, ordered an investigation. The investigation discovered that the march was financed by Mellon. Mellon's motives may be difficult to understand, but the action undermined Hoover's faith in his Treasury Secretary. This, coupled with the impeachment hearing (below) led to Mellon's resignation.[16]

In January 1932, Rep. Wright Patman (D-TX) (later an F.D.R. New Deal supporter) and others introduced articles of impeachment against Mellon,[17] with hearings before the House Judiciary Committee at the end of that month.[18] After the hearings were over, but before the scheduled vote on whether to report the articles to the full House, Mellon accepted an appointment to the post of Ambassador to the Court of St. James and resigned as Treasury secretary in February. He served for one year as ambassador and then retired to private life. Representative Louis Thomas McFadden (R-PA) invoked Mellon's appointment while an impeachment was pending in his subsequent attempt to impeach President Hoover.

Personal life

In 1900, Mellon, then 45 years old, married Nora Mary McMullen (1879–1973), a 20-year-old Englishwoman who was the daughter of Alexander P. McMullen,[19] a major shareholder of the Guinness Brewing Co. They had two children, Ailsa, born in 1901, and Paul, born in 1907. Their marriage ended in a bitter divorce in 1912, which was granted on grounds of Nora Mellon's desertion and her adultery with Capt. George Alfred Curphey, an English soldier, and other men.[19] Mellon did not remarry. In 1923 his former wife married Harvey Arthur Lee, a British-born antiques dealer 14 years her junior.[20] Two years after the Lees' divorce in 1928, Nora Lee resumed the surname Mellon, at the request of her son, Paul.[21]

Philanthropy

In 1913, along with his brother, Richard B. Mellon, he established a memorial for his father, the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research, as a department of the University of Pittsburgh. Today the institute is a part of Carnegie Mellon University. Mellon also served as an alumni president[22] and trustee[23] of the University of Pittsburgh, and made several major donations to the school, including the land on which the Cathedral of Learning and Heinz Chapel were constructed.[24] In total it is estimated that Mellon donated over $43 million to the University of Pittsburgh.[25] During World War I he participated in many fundraising activities such as the American Red Cross, the National War Council of the Y.M.C.A., the Executive Committee of the Pennsylvania State Council of National Defense, and the National Research Council of Washington.

During his retirement years, as he had done in earlier years, Mellon was an active philanthropist, and gave generously of his private fortune to support art and research causes.[26] In 1937, he donated his substantial art collection, collected at a cost of $25 million and valued at $40 million, plus $10 million for construction,[27] to establish the National Gallery of Art on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The Gallery was authorized in 1937 by Congress.

The Mellon tax trial

The administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt subjected Mellon to intense investigation of his personal income tax returns. The US Justice Department empaneled a grand jury, which declined to issue an indictment. Roosevelt hated Mellon, as the embodiment of everything he thought was bad about the 1920s; Mellon vehemently denied the charges. A two-year civil action beginning in 1935, dubbed the "Mellon Tax Trial", eventually exonerated Mellon, albeit several months after his death.

Death

Mellon died on August 26, 1937, in Southampton, Long Island, New York, and was buried at Trinity Episcopal Church Cemetery, Upperville, Virginia.

Legacy

The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the product of the merger of the Avalon Foundation and the Old Dominion Foundation (set up separately by his children), is named in his honor, as is the 378-foot US Coast Guard Cutter Mellon (WHEC-717). Washington, D.C.'s Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium and Andrew Mellon Building were both named in Mellon's honor as was the National Gallery of Art during its early years.

Books

- Mellon, Andrew W., Taxation: The People's Business

In popular culture

Andrew W. Mellon appears in the HBO drama series Boardwalk Empire, in the fifth, eighth and twelfth episodes of the third season, in his capacity as Secretary of the Treasury. His character is played by Carnegie Mellon alumnus James Cromwell.

See also

- Mellonomics.

- In Sunlight, In a Beautiful Garden, a novel by Kathleen Cambor about the Johnstown flood.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Cannadine, David. Mellon: An American Life. New York: A.A. Knopf, 2006. pp. 48-49, 165, 349. ISBN 0-679-45032-7.

- ↑ Bennett, Robert A. "Mellon Bank stumbles over merger." Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 11, 1986. pp 17, 19. Google News Archives. Retrieved October 15, 2013.

- ↑ Ingham, John N. Biographical Dictionary of American Business Leaders, Vol. 2. ISBN 0313239088. Google Books. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ↑ Love, Philip H. (2003-06-01). Andrew W. Mellon: The Man and His Work. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 136–136. ISBN 978-0-7661-6111-5. Retrieved 2013-07-12.

- ↑ "Mellon Starts Real Vacation". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. July 30, 1931.

- ↑ Mellon, Andrew W. (1924). Taxation: The People's Business. New York: Macmillan. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-405-05101-2.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Folsom, Burton W. Jr. (1987). The Myth of the Robber Barons. Young America's Foundation. ISBN 978-0-9630203-1-4.

- ↑ Thorndike, Joseph J. (24 Mar 2003). "Was Andrew Mellon Really the Supply Sider That Conservatives Like to Believe?". Tax History Project.

- ↑ Mellon, Andrew W. (1924). Taxation: The People's Business. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 56–57. Archived from the original on 28 April 2005. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ Government Debt Chart: United States 1920-1930 - Federal State Local Data. www.usgovernmentdebt.us. Retrieved on 2013-07-17.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Murnane, M. S. (2006). The mellon tax plan: The income tax and the penetration of marginalist economic thought into american life and law in the 1920s. (Order No. 3240536, Case Western Reserve University). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, , 441-441 p. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/docview/305354571?accountid=14816. (305354571).

- ↑ Ward, D. (n.d.). Population Growth, Migration, and Urbanization, 1860-1920. Population Growth, Migration, and Urbanization, 1860-1920. Retrieved October 6, 2014, from https://cascourses.uoregon.edu/geog471/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/WardImmigration.pdf

- ↑ Hoover, Herbert. The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover, Volume 3: The Great Depression. Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum. www.hoover.nara.gov. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ↑ White, Lawrence H. "Did Hayek and Robbins Deepen the Great Depression?," Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 40, No. 4, (June 2008), pp. 758-60.

- ↑ "Mellon Denies Liquor Interests." The Free Lance-Star (Fredericksburg, Virginia), September 27, 1928. Google News Archives. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ↑ Dailey, Ruth Ann (March 26, 2012). "The Mystery of Mellon's Motive". Post-Gazette (Pittsburgh). and Barcousky, Len (January 8, 2012). "Eyewitness 1932: Pittsburgh minister leads 'army' to D.C.". Post-Gazette (Pittsburgh).

- ↑ "Wright Patman Impeachment motion - Andrew Mellon." Congressional Record - House, 1932, pp.1398–1401. www.scribd.com. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ↑ "National Affairs: Texan, Texan & Texan". TIME. 25 Jan 1932. www.time.com. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Mary Conover." www.thepeerage.com. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Milestones: Jun. 11, 1928". TIME. 11 June 1928. www.time.com. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Names make news". TIME. August 18, 1930. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ The 1937 Owl. University of Pittsburgh. 1937. p. 32. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- ↑ Alberts, Robert C. (1986). Pitt: The Story of the University of Pittsburgh 1787–1987. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-8229-1150-7. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- ↑ Starrett, Agnes Lynch (1937). Through one hundred and fifty years: the University of Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 256. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- ↑ Alberts, Robert C. (1986). Pitt: The Story of the University of Pittsburgh 1787–1987. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 182. ISBN 0-8229-1150-7. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- ↑ The Philanthropy Hall of Fame, Andrew Mellon

- ↑ Laurent, Stefan. "Historic Pittsburgh Chronology". Historic Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

Bibliography

- Cannadine, David. Mellon: An American Life. New York: A.A. Knopf, 2006. ISBN 0-679-45032-7.

- Finley, David Edward. A Standard of Excellence: Andrew W. Mellon Founds the National Gallery of Art. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1975. ISBN 0874741327.

- Folsom, Burton W., Jr. The Myth of the Robber Barons (A New Look at the Rise of Big Business in America). Herndon, Virginia: Young America's Foundation, 1991. ISBN 0963020315.

- Holbrook, Stewart H. The Age of the Moguls. New York: Harmony Books, 1985. ISBN 0517556790 (Original work published 1953).

- Koskoff, David E. The Mellons: The Chronicle of America's Richest Family. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1978. ISBN 0690011903.

- Mellon, Andrew. Taxation: The People's Business. S.I.: Gale, 2011. ISBN 124012709X (Original work published 1924).

- O'Connor, Harvey. Mellon's Millions, the Biography of a Fortune: The Life and Times of Andrew W. Mellon. New York: John Day Company, 1933. ISBN 9110118934.

- Thorndike, Joseph J. (24 March 2003). "Was Andrew Mellon Really the Supply Sider That Conservatives Like to Believe?". Tax History Project.

- "Andrew W. Mellon." U.S. Treasury.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Andrew W. Mellon. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Andrew W. Mellon. |

- The Andrew W. Mellon – Mellon Foundation Biography by David Cannadine

- The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation

- Overview of Mellon Tax Cut Plans

- Andrew W. Mellon and the National Gallery

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article on history of the Mellons and Mellon Financial

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette series on Mellon's involvement in the oil industry and mid-east oil

- "Andrew W. Mellon". Find a Grave. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- "The Published Writings of Herbert Hoover." Herbert Hoover Presidential Library.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by David F. Houston |

U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Served under: Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover March 4, 1921 – February 12, 1932 |

Succeeded by Ogden L. Mills |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by Charles G. Dawes |

US Ambassador to the United Kingdom 1932–1933 |

Succeeded by Robert Worth Bingham |

| Awards and achievements | ||

| Preceded by Edward M. House |

Cover of Time Magazine 2 July 1923 |

Succeeded by Mason M. Patrick |

| Preceded by John D. Rockefeller |

Cover of Time Magazine 28 May 1928 |

Succeeded by John Dewey |

| ||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|