Anderson Creek (Pennsylvania)

Anderson Creek is a 23.6-mile-long (38.0 km)[1] tributary of the West Branch Susquehanna River in Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, in the United States.[2]

The upstream portion of the Anderson Creek Watershed is a PA DCNR Conservation Area, and falls from Rockton Mountain, the highest mountain east of the Mississippi River on Interstate I-80 in Clearfield County, Pennsylvania.[3] Anderson Creek is classified as a Class II-III+ whitewater stream and defines the Eastern Continental Divide.[4] Brown Springs, in the Moshannon State Forest, near Rockton, Pennsylvania, is a put-in for kayaking to the West Branch Susquehanna River at Bridgeport, Pennsylvania. The vertical drop of Anderson Creek is 1450 ft. to 1175 ft. "Anderson is a stream of considerable size, and in a region not so well supplied with raftable waters as this, might be well classed among rivers."[5]

Great Shamokin Path

The Anderson Creek corridor is part of the Great Shamokin Path from the native village Shamokin, on the Susquehanna River, to Kittanning, Pennsylvania, on the Allegheny River. The path ascended the steep Anderson Creek Gorge several miles, then it turned west at what is now known as Chestnut Grove, Bloom Township, Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, and then on to The Big Spring near Luthersburg, Brady Township, Pennsylvania.

Bilger's Rocks Prehistoric Site

The Anderson Creek corridor is the location of the Bilger's Rocks prehistoric McFate Culture site.[6] During the latter portion of the Late Woodland Period (A.D. 1000–1580) groups belonging to the McFate culture inhabited portions of along the Allegheny Front in north central Pennsylvania. The site is in Bloom Township, Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, near the town of Grampian, Pennsylvania. The Bilger’s Rocks Association owns and cares for the 175-acre tract and conducts educational programs for visitors.[7] McFate sites have been located in Clearfield and Elk counties. A McFate site near Du Bois, Pennsylvania, the Hickory Kingdom "Kalgren site", was a stockaded fort on a projecting point of the Eastern Continental Divide and close to trail systems.[8]

Early native peoples

Artifacts from the Curwensville, Pennsylvania, area demonstrate that various groups of Native Americans occupied the confluence of Anderson Creek and West Susquehanna Branch over a 10,000-year period.[9] From AD 1000 to AD 1600, at least half a dozen groups lived in the vicinity of the Anderson Creek; the Clemson Island, Owasco, Shenks Ferry, Monongahela, and McFate or Black Minquas who were the last tribal entity to occupy the corridor. The Senecas from northern Pennsylvania wiped them out about 1650.

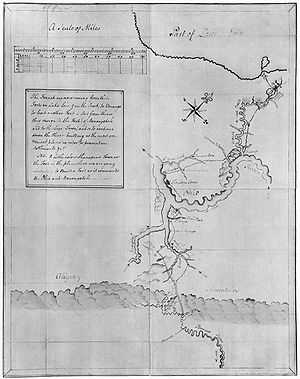

The French and Indian War

During the French and Indian War in 1757–1758, several hundred French and Indian troops traveled the Great Shamokin Path in an effort to destroy Fort Augusta, the main stronghold of the English at the junction of the east and west branches of the Susquehanna River. This army was gathered from the French posts at Duquesne, Kittanning, Venango and Le Boeuf and assembled at the mouth of Anderson Creek. Here, crude boats, rafts and bateau were constructed for passage down the Susquehanna River for the proposed attack. They dragged along with them two small brass cannon, but after reconnoitering found the distance too great for the guns to shoot from the hill opposite the fort. The defense at Fort Augusta was strong enough to resist attack by storming or by siege, and the attack was abandoned. A British defeat at Fort Augusta could have altered the history of the course of the French and Indian War.[10]

Moravian expeditions

The Anderson Creek corridor is part of the Great Shamokin Path from the native village Shamokin, on the Susquehanna River, to Kittanning, Pennsylvania, on the Allegheny River. The Anderson Creek area was known by Native Americans as "the place where there is a mountain halfway on the other side". Native Americans recognized that Anderson Creek was the boundary between two river systems, the Susquehanna River and the Ohio River. For several decades in the early 18th century, the villages of Shamokin and Kittanning were two of the most important Native American villages in Pennsylvania. Perhaps the path's best known use was by Moravian Bishop John Ettwein and his group of some 200 Lenape and Mohican Christians in 1772. They traveled west along the path from their village of Friedenshütten (Cabins of Peace) near modern Wyalusing on the North Branch Susquehanna River to their new village of Friedensstadt on the Beaver River in southwestern Pennsylvania.

The private travel diary of the Rev. Johann Roth, a Moravian Church missionary among the Indians in the American East, describes his journey along the Anderson Creek corridor in the summer of 1772. In this account of his day-by-day progress, the Rev. Roth mentions a number of Delaware (or Lenni Lenape) Indian names for Pennsylvania. Roth mentions a night camp in a region which the Indians called "Wachtschunglelawi awossijaje." These are really three words, Wachtschiink leldwi awossijaje: wachtsch[u], 'a hill, mountain'; -iink, locative suffix, 'place where'; leldwi, 'halfway, in the middle'; awossijaje, 'over, over there, beyond, on the other side, behind.' This makes the three words signify, 'place where there is a mountain halfway on the other side'; or, rather, 'where there is a mountain halfway between the one side and the other.' That is, 'a divide' between two river systems; in this case, between the Susquehanna River and the Ohio River.[11]

The Mead brothers and French Creek

In his report to Governor Robert Dinwiddie, George Washington made reference to a beautiful rolling country, suitable for settlement, that he had found along the waters of French Creek. In 1788, brothers John and David Mead were ready to investigate Washington's story, and left Fort Augusta, now Sunbury, Pennsylvania, to explore the far west. They journeyed up mouth of Anderson Creek and turned at Coal Hill towards camp site and crossroads at The Big Spring. From there, they continued northwest on the Goschgoschink Path to the Venango Path and the waters of French Creek.[10] On May 12, 1788, the Mead brothers founded Meadville, Pennsylvania, at the confluence of Cussewago Creek and French Creek.

War of 1812

During the War of 1812, Major William McClelland departed Fort Loudoun, near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, on March 4, 1814 and marched a division of troops numbering two hundred and twenty-one privates, three captains. five lieutenants and two ensigns along Anderson Creek to meet the Goschgoschink Path, later known as Mead's Path, at The Big Spring, Brady Township, Pennsylvania.[12] These soldiers with their wagon train of equipment and cannon camped at Thunderbird Spring (Old State Road), just east of Kiwanis Trail, and near the Jefferson–Clearfield County Line. The march from Fort Loudoun to Erie took twenty-eight days.[13] Major William McClelland's division relieved American forces at Lake Erie and later gave a good account of themselves at the Battle of Chippewa and Battle of Lundy’s Lane.[14]

Underground Railroad

The various paths, river routes and safe waypoints that escaped slaves and their guides used in their journey northwards towards freedom are collectively known as the Underground Railroad. In western Pennsylvania, routes began at the Maryland–Pennsylvania border and traveled through Bedford, Pennsylvania, where the route split and converged at the Great Shamokin Path at the mouth of Anderson Creek. From there, the route led to The Big Spring near Luthersburg, Pennsylvania, and thence on Meade's Path to the Venango Path, Lake Erie and onward to Canada. Quaker settlers living along the Great Shamokin Path in Clearfield County did what they could to assist escaped slaves. The natural topography and terrain of the Eastern Continental Divide provided excellent cover and access to the zigzagging, sometimes backtracking, and myriad alternative routes that were needed to ensure the secrecy of the "Railroad."[15]

Anderson Creek corridor

The historic Anderson Creek corridor was later used for railroad passenger travel and commercial transportation of logs, coal and stone. Early settlers established logging mills and villages along Anderson Creek, and a railroad from Du Bois, Pennsylvania, to Curwensville, Pennsylvania, was completed in 1893. The settlement of Home Camp, Union Township, was once a thriving logging town with saw mills, splash dams and boarding houses for lumbermen. Water was sufficient for floating logs to the West Branch Susquehanna River. The last log drive on Anderson Creek was in 1901.[16] The area is also rich in history from more recent times. During the Golden Age of railroading, passengers and freight rolled along this route, taking students to school and soldiers to war. Millions of tons of coal were pulled along this route, and stone quarried for bridges and buildings throughout the East. Clay was also extracted, with brickyards all along the tracks. Raftsmen plied the Susquehanna, riding logs to market hundreds of miles downstream. The resources help fuel the industrial might of the nation. This trail today is a resource as precious as the coal, timber, stone, and clay carried on the rails along this corridor.[17] Recently, the Anderson Creek corridor has been considered as a venue for environmental and recreational tourism.[18]

The Bickford Railroad Line

In 1881, the shipping interests of the Buffalo, Rochester and Pittsburgh Railway became eager to have an eastern outlet and what is known as the Clearfield & Mahoning Railroad Company obtained a charter from the State and built a line from C. & M. Junction in Brady Township, Pennsylvania, by way of Luthersburg and Curwensville, to Clearfield, Pennsylvania. The first construction work was started in June 1892, and the first passenger train over this road was run on the first day of June 1893. The line is 17.4 miles long and is named after the Bickford junction west of Curwensville.[19] The Bickford Line traveled along the Eastern Continental Divide bounding Anderson Creek from Rockton, Union Township, Pennsylvania, to the West Branch Susquehanna River at Bridgeport, Pennsylvania. The line is no longer active and the rails have been removed. The last passenger train ride on the Bickford Line from Du Bois to Clearfield was on June 15, 1954, and hundreds of local residents enjoyed the historic journey. The railroad tracks have been removed and the ownership of the right-of-way is uncertain.[20] The old rail line is popular with ATV enthusiasts.

Du Bois Reservoir

The Du Bois Reservoir in Union Township, Clearfield County, consists of 210 acres, has a listed capacity of 615 million gallons and is located near the headwaters of Anderson Creek. The reservoir is a PA DCNR Conservation Area and serves as the water supply for the City of Du Bois. The Du Bois Reservoir is also known as the Anderson Creek Reservoir. The dam at Du Bois Reservoir controls the flow of water from the headwaters of Anderson Creek.

Village of Rockton

Rockton is a village in Union Township, Clearfield County, resting along Anderson Creek near Brown Springs in the Moshannon State Forest. Rockton gets its name from a time when the stagecoach came over the mountain from Clearfield with the mail, and passengers would argue about the weight of a large rock.[21] Rockton had its own school, weekly newspaper, several stores, three churches, a number of mills, both grist and lumber, and an emergency landing field for air mail pilots. Farms did well in the shelter of the surrounding mountains.

Rockton was divided in two, upper and lower. What is known as Rockton today was begun through lumbering by people such as John Brubaker. In 1885, Jason E. Kirk and David W. Kirk built a steam-powered feed mill. Lower Rockton began in 1837 with a saw mill and grist mill built by Jason Kirk and Jeremiah Moore. It sits along Anderson Creek as did the wool mill of William Johnson. The Kirk mill was designed to provide adequate height and space at the front of the building for men and horse-drawn wagons to load and unload products.

Rockton once had rail service on the Bickford Line from Du Bois to Clearfield. The Buffalo, Rochester & Pittsburgh Rockton Station built in 1898 was dismantled in the 1970s and is now in Kane, Pennsylvania.[22]

The greatest disaster for Rockton was a tornado on September 14, 1945, beginning in the Coal Hill area of Brady Township. Many buildings were destroyed with the Hollopeter Poultry Farm receiving most of the damage. The William Irwin house was moved several inches off of its foundation and a barn demolished. The storm cleared a path approximately 100 feet wide and eight miles long. After the storm crossed Anderson Creek and moved up Montgomery Run, it dispersed. No one was injured.

Today, Rockton has a post office, two churches, St. John’s Lutheran and the Church of the Brethren, a gas station, a fast-food restaurant, and several shops.[23]

David S. Ammerman Trail

Once known as the Clearfield and Grampian Trail, in 2011, the name was changed to the David S. Ammerman Trail in memory of the man who championed turning the abandoned rail corridor into a recreational trail. The David S. Ammerman Trail traverses Anderson Creek in Curwensville, Pennsylvania, and connects to Grampian, Pennsylvania, and Clearfield, Pennsylvania.

Anderson Creek Watershed Association

The Anderson Creek Watershed Association has partnered projects with the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy Watershed Restoration Project. Clearfield County has more acreage affected by abandoned mines than any county in the state.[24]

See also

- List of Pennsylvania rivers

References

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map, accessed August 8, 2011

- ↑ Gertler, Edward. Keystone Canoeing, Seneca Press, 2004. ISBN 0-9749692-0-6

- ↑ Rockton Mountain is a popular recreation area for mountain biking and snowmobiling.

- ↑ See http://www.americanwhitewater.org./

- ↑ Aldrich, History of Clearfield County, pp. 652, 1887.

- ↑ Bilger’s Rocks lies within the heart of the Mid-Atlantic Highlands of the Appalachian Mountains. The area has a rich mix of animal and plant species. There are more than 6,200 caves in the Mid-Atlantic Highlands which shelter a less visible but fascinating habitat for cave crickets, albino spiders, blind salamanders and endangered bats. In 2000, the Nature Conservancy made the region one of its top conservation priorities because of its biological richness. See "Common ground: Highlands' program links environment, economy" at www.bayjournal.com/article.cfm?article=3211

- ↑ Rocks suddenly appear along the side of the road, big monoliths of stone with fissures and cracks, which seem to lead to paths and perhaps caves within the rocks. Just past this outcropping is a parking area, concession stand, some picnic tables, a playground and a pavilion. Jaime Kostelink and Jim Shaulis of DCNR's geological survey explored Bilger’s Rocks to determine if the site belongs on the Pennsylvania National Heritage Site list. There are 270 acres of rocks and rock outcroppings involved in the project. It was noted that the age of the rocks are between 275 to 300 million years old. The site was visited by Native Americans and immigrants for thousands of years and is the home of a rare fern that only grows in certain places in the country. One of the dreams of the Bilger’s Rocks Association is to build an education and classroom center. Designation as a Pennsylvania National Heritage Site requires that the site have scientific and educational value, scenic value, recreational value and historical value. “Bilger's Rocks may be designated as heritage site”, The Progress, July 06, 2007. See www.offroaders.com/album/clearfield/clear1099/bilgers.html.

- ↑ See MacMinn, "Indian Forts in Hickory Kingdom" in Matclack, Indians of Clearfield County 10,000 BC to 1800 AD, Clearfield County Historical Society, 1990. The site is six miles northeast of the City of Du Bois in Sandy Township. See Myers, "An Examination of Late Prehistoric McFate Trail Locations" in PA Archaeology at www.pennsylvaniaarchaeology.com.

- ↑ "In the heart of Curwensville once stood a blacksmith shop owned by Paul Clover. Here he raised his family in the late 1700s. A daughter, Nancy, is the first white settler buried in this area. A large marker on a plot of ground next to the Curwensville VFW Post is her final resting place. She died in 1804. This historical burial ground on River Street near the VFW is believed to be a place where the Shawnees, a sub-tribe of the Leni-Lenape Indians of Algonquin stock who inhabited Clearfield County at that time, buried their dead. Clearfield County Comprehensive Plan, Chapter 4: History, Resource Inventory & Preservation Plan, 2006, p.2, 36.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 M.I. McCreight, Du Bois History, Memory Sketches of Du Bois, Pennsylvania: A History, (1939), p.69.

- ↑ This divide extends over Brady and Bell Twps., Clearfield County." Mahr, "How to Locate Indian Places on Modern Maps", The Ohio Journal of Science, May 1953, pp. 129, 134.

- ↑ "The Goschgoschink Path begins at the junction of the Great Shamokin Path at "Big Spring" near Luthersburg. The path then proceeds to Thunderbird Spring, Sandy Valley Station, north of Reynoldsville, thence through the Horme Settlement and slightly north of Emerickville to Brookville; north of Clarion, to Franklin and along French Creek to LeBoeuf and Presque Isle at Lake Erie.

- ↑ They encamped at Soldier’s Run, in what is now Winslow Township, rested at Port Barnett for four days, and encamped over night at the "four mile spring", on what is now the Afton farm. Elijah M. Graham was impressed with his two "pack horses" into their service, and was taken as far as French Creek, now in Venango County. These soldiers were volunteers and were from Franklin County. Major McClelland, with his officers and men, passed through where Brookville now is. Three detachments of troops left Franklin County during the years 1812–1814 at three different times, one by way of Pittsburgh, one by way of Baltimore, and the last through this wilderness. Upon the arrival of these troops at Erie they were put into the Fifth Regiment of the Pennsylvania troops, commanded by Col. James Fenton, of that regiment, the whole army being under the command of Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown. These soldiers fought in the desperate battles of Chippewa and Lundy’s Lane, on July 5 and 25, 1814. William James McKnight, M.D., A Pioneer History of Northwestern Pennsylvania, 1905, p.243.

- ↑ Major Israel McCreight, Memory Sketches of Du Bois Pennsylvania 1874-1938: A History, (1939) at pp. 68–71. See Wallace, Indian Paths of Pennsylvania, (1965), at p.61.

- ↑ Switala, William J. The Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania pp. 30–37, 2001.

- ↑ Hughes, A Twentieth Century History of Clearfield County, Pa. (1900-2000), 2006, at 1290–1291.

- ↑ See Skip Cleaver on the Clearfield-Grampian Trail.

- ↑ "Local citizens look optimistically at the Anderson Creek Gorge as a major recreational draw for the region. An abandoned railroad traverses much of the Anderson Creek Gorge and development of a rail-to-trail using this rail line would connect nicely with the trail along Kratzer Run and the West Branch Susquehanna River. Additionally, other nearby rail trails could be connected to an Anderson Creek rail trail. Improving the water resource will be a key to developing any additional recreational and economic value within the watershed. Recreational boaters also consider Anderson Creek a challenging whitewater stream. Its numerous rapids and remote character make it an appealing whitewater run. Only its poor water quality degrades what could be a premier boating experience." Anderson Creek Watershed: Assessment, Restoration, and Implementation Plan, Western PA Conservancy, PA DEP and U.S. EPA at II-19, September 2006. See Anderson Creek AMD Assessment, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy at www.paconserve.org/116/watershed-restoration-projects.

- ↑ Pentz, William C., The City of Du Bois, pp. 161–162, 1932.

- ↑ "Reconnecting the B&P with the RJC in Clearfield would provide a needed 18-mile connection." See North Central PA LRTP at p. 44.

- ↑ Hughes at 1297.

- ↑ The Rockton (BR&P) Station was originally built in 1898 for the Buffalo, Rochester & Pittsburgh Railroad at Rockton, Pennsylvania, on the Clearfield Branch. The depot was dismantled and first moved to Sloan Cornell's Penn View Mountain Railroad near Blairsville, Pennsylvania, in the 1970s. The depot was dismantled and moved a second time to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on Sloan Cornell's Gettysburg Railroad in the late '70s. An expansion of the nearby Gettysburg College later necessitated the station to be dismantled and placed in storage. The station was moved a third time and recently reassembled in Kane, Pennsylvania, on Cornell's Knox and Kane Railroad. The reassembly was in progress when a tornado destroyed several piers of the Kinzua Bridge. The station has been finished, but regular passenger and freight service has ceased on the K&K, and the railroad is for sale. – See Kevin Moore, 2007, at http://www.west2k.com/pastations/clearfield.shtml.

- ↑ Gene M. Aravich, Du Bois Area Historical Society at http://duboishs.com/index.php/rockton/

- ↑ The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania will receive approximately $1.4 billion in federal funds over 15 years to clean up abandoned mines in the state. Clearfield County has more acreage affected by abandoned mines than any county in the state. "DEP seeks input on mine cleanup", Progress, September 13, 2007, p. 1.