Anamorphism

In category theory, the concept of anamorphism ("ana" from the Greek ἀνά = upwards; "morphism" from the Greek μορφή = form, shape) denotes a morphism from a coalgebra to the final coalgebra for that endofunctor. These objects have been applied to functional programming as unfolds. The categorical dual of the anamorphism is the catamorphism.

Anamorphisms in functional programming

In functional programming, an anamorphism is a generalization of the concept of unfolds on lists. Formally, anamorphisms are generic functions that can corecursively construct a result of a certain type and which is parameterized by functions that determine the next single step of the construction.

Example

An unfold on lists would build a (potentially infinite) list from a seed value. Typically, the unfold takes a seed value x, a one-place operation unspool that yields a pairs of such items, and a predicate finished which determines when to finish the list (if ever). In the action of unfold, the first application of unspool, to the seed x, would yield unspool x => (y,z). The list defined by the unfold would then begin with y and be followed with the (potentially infinite) list that unfolds from the second term, z, with the same operations. So if unspool z => (u,v), then the list will begin y:u:..., where ... is the result of unfolding v with r, and so on.

A Haskell definition of an unfold, or anamorphism for lists, called ana, is as follows:

-- The type signature of 'ana': ana :: (state -> (value, state)) -> (state -> Bool) -> state -> [value] -- Its definition: ana unspool finished state = if finished state then [] else value : (ana unspool finished state') where (value, state') = unspool state

(Here finished and unspool are parameters of the function, like state.)

In the case where we're finished (finished x == True), we do not use unspool x. We can thus group together unspool and finished into one function f :: (b -> Maybe (a,b)), where f x => Just (a,y) means finished x == False and unspool x == (a,y), while f x == Nothing means we're done (finished x == True). We now have:

-- The type signature of 'ana': ana :: (b -> Maybe (a,b)) -> b -> [a] -- Its definition: ana f x = case (f x) of Nothing -> [] Just (a,y) -> a:(ana f y)

We can now implement quite general functions using ana.

Anamorphisms on other data structures

An anamorphism can be defined for any recursive type, according to a generic pattern, generalizing the second version of ana for lists.

For example, the unfold for the tree data structure

data Tree a = Leaf a | Branch (Tree a) a (Tree a)

is as follows

ana :: (b->Either a (b,a,b)) -> b -> Tree a ana unspool x = case unspool x of Left a -> Leaf a Right (l,x,r) -> Branch (ana unspool l) x (ana unspool r)

To better see the relationship between the recursive type and its anamorphism, note that Tree and List can be defined thus:

newtype List a = List {unCons :: Maybe (a, List a)} newtype Tree a = Tree {unNode :: Either a (Tree a, a, Tree a))}

The analogy with ana appears by renaming b in its type:

newtype List a = List {unCons :: Maybe (a, List a)} anaList :: ( list_a -> Maybe (a, list_a)) -> (list_a -> List a) newtype Tree a = Tree {unNode :: Either a (Tree a, a, Tree a))} anaTree :: (tree_a -> Either a (tree_a, a, tree_a)) -> (tree_a -> Tree a)

With these definitions, the argument to the constructor of the type has the same type as the return type of the first argument of ana, with the recursive mentions of the type replaced with b.

History

One of the first publications to introduce the notion of an anamorphism in the context of programming was the paper Functional Programming with Bananas, Lenses, Envelopes and Barbed Wire,[1] by Erik Meijer et al., which was in the context of the Squiggol programming language.

Applications

Functions like zip and iterate are examples of anamorphisms. zip takes a pair of lists, say ['a','b','c'] and [1,2,3] and returns a list of pairs [('a',1),('b',2),('c',3)]. Iterate takes a thing, x, and a function, f, from such things to such things, and returns the infinite list that comes from repeated application of f, i.e. the list [x, (f x), (f (f x)), (f (f (f x))), ...].

zip (a:as) (b:bs) = if (as==[]) || (bs ==[]) -- || means 'or' then [(a,b)] else (a,b):(zip as bs) iterate f x = x:(iterate f (f x))

To prove this, we can implement both using our generic unfold, ana, using a simple recursive routine:

zip2 = ana unsp fin where fin (as,bs) = (as==[]) || (bs ==[]) unsp ((a:as), (b:bs)) = ((a,b),(as,bs)) iterate2 f = ana (\a->(a,f a)) (\x->False)

In a language like Haskell, even the abstract functions fold, unfold and ana are merely defined terms, as we have seen from the definitions given above.

Anamorphisms in category theory

In category theory, anamorphisms are the categorical dual of catamorphisms (and catamorphisms are the categorical dual of anamorphisms).

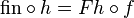

That means the following. Suppose (A, fin) is a final F-coalgebra for some endofunctor F of some category into itself. Thus, fin is a morphism from A to FA, and since it is assumed to be final we know that whenever (X, f) is another F-coalgebra (a morphism f from X to FX), there will be a unique homomorphism h from (X, f) to (A, fin), that is a morphism h from X to A such that fin . h = Fh . f. Then for each such f we denote by ana f that uniquely specified morphism h.

In other words, we have the following defining relationship, given some fixed F, A, and fin as above:

Notation

A notation for ana f found in the literature is ![[\!(f)\!]](../I/m/66214b56426b80e3463c1a6d75778b52.png) . The brackets used are known as lens brackets, after which anamorphisms are sometimes referred to as lenses.

. The brackets used are known as lens brackets, after which anamorphisms are sometimes referred to as lenses.

See also

References

- ↑ Meijer, Erik; Fokkinga, Maarten; Paterson, Ross (1991). "Functional Programming with Bananas, Lenses, Envelopes and Barbed Wire". CiteSeerX: 10

.1 ..1 .41 .125