Amine gas treating

NUST, also known as amine scrubbing, gas sweetening and acid gas removal, refers to a group of processes that use aqueous solutions of various alkylamines (commonly referred to simply as amines) to remove hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and carbon dioxide (CO2) from gases.[1][2][3] It is a common unit process used in refineries, and is also used in petrochemical plants, natural gas processing plants and other industries.

Processes within oil refineries or chemical processing plants that remove hydrogen sulfide are referred to as "sweetening" processes because the odor of the processed products is improved by the absence of hydrogen sulfide. An alternative to the use of amines involves membrane technology. However, membranes are less attractive since the relatively high capital and operation costs as well as other technical factors. [4]

Many different amines are used in gas treating:

- Diethanolamine (DEA)

- Monoethanolamine (MEA)

- Methyldiethanolamine (MDEA)

- Diisopropanolamine (DIPA)

- Aminoethoxyethanol (Diglycolamine) (DGA)

The most commonly used amines in industrial plants are the alkanolamines DEA, MEA, and MDEA. These amines are also used in many oil refineries to remove sour gases from liquid hydrocarbons such as liquified petroleum gas (LPG).

Description of a typical amine treater

Gases containing H2S or both H2S and CO2 are commonly referred to as sour gases or acid gases in the hydrocarbon processing industries.

The chemistry involved in the amine treating of such gases varies somewhat with the particular amine being used. For one of the more common amines, monoethanolamine (MEA) denoted as RNH2, the chemistry may be expressed as:

- RNH2 + H2S

RNH+

RNH+

3 + SH−

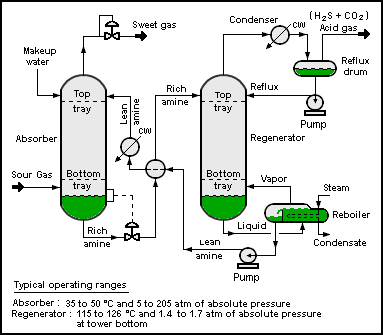

A typical amine gas treating process (as shown in the flow diagram below) includes an absorber unit and a regenerator unit as well as accessory equipment. In the absorber, the downflowing amine solution absorbs H2S and CO2 from the upflowing sour gas to produce a sweetened gas stream (i.e., a gas free of hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide) as a product and an amine solution rich in the absorbed acid gases. The resultant "rich" amine is then routed into the regenerator (a stripper with a reboiler) to produce regenerated or "lean" amine that is recycled for reuse in the absorber. The stripped overhead gas from the regenerator is concentrated H2S and CO2.

Amines

The amine concentration in the absorbent aqueous solution is an important parameter in the design and operation of an amine gas treating process. Depending on which one of the following four amines the unit was designed to use and what gases it was designed to remove, these are some typical amine concentrations, expressed as weight percent of pure amine in the aqueous solution:[1]

- Monoethanolamine: About 20 % for removing H2S and CO2, and about 32 % for removing only CO2.

- Diethanolamine: About 20 to 25 % for removing H2S and CO2

- Methyldiethanolamine: About 30 to 55% % for removing H2S and CO2

- Diglycolamine: About 50 % for removing H2S and CO2

The choice of amine concentration in the circulating aqueous solution depends upon a number of factors and may be quite arbitrary. It is usually made simply on the basis of experience. The factors involved include whether the amine unit is treating raw natural gas or petroleum refinery by-product gases that contain relatively low concentrations of both H2S and CO2 or whether the unit is treating gases with a high percentage of CO2 such as the offgas from the steam reforming process used in ammonia production or the flue gases from power plants.[1]

Both H2S and CO2 are acid gases and hence corrosive to carbon steel. However, in an amine treating unit, CO2 is the stronger acid of the two. H2S forms a film of iron sulfide on the surface of the steel that acts to protect the steel. When treating gases with a high percentage of CO2, corrosion inhibitors are often used and that permits the use of higher concentrations of amine in the circulating solution.

Another factor involved in choosing an amine concentration is the relative solubility of H2S and CO2 in the selected amine.[1] The choice of the type of amine will affect the required circulation rate of amine solution, the energy consumption for the regeneration and the ability to selectively remove either H2S alone or CO2 alone if desired. For more information about selecting the amine concentration, the reader is referred to Kohl and Nielsen's book.

Activated MDEA or aMDEA uses piperazine as a catalyst to increase the speed of the reaction with CO2. It has been commercially successful.[5]

Uses

In oil refineries, that stripped gas is mostly H2S, much of which often comes from a sulfur-removing process called hydrodesulfurization. This H2S-rich stripped gas stream is then usually routed into a Claus process to convert it into elemental sulfur. In fact, the vast majority of the 64,000,000 metric tons of sulfur produced worldwide in 2005 was byproduct sulfur from refineries and other hydrocarbon processing plants.[6][7] Another sulfur-removing process is the WSA Process which recovers sulfur in any form as concentrated sulfuric acid. In some plants, more than one amine absorber unit may share a common regenerator unit. The current emphasis on removing CO2 from the flue gases emitted by fossil fuel power plants has led to much interest in using amines for removing CO2. (See also: Carbon capture and storage and Conventional coal-fired power plant.)

In the specific case of the industrial synthesis of ammonia, for the steam reforming process of hydrocarbons to produce gaseous hydrogen, amine treating is one of the commonly used processes for removing excess carbon dioxide in the final purification of the gaseous hydrogen.

See also

- Ammonia production

- Hydrodesulfurization

- WSA Process

- Claus process

- Selexol

- Rectisol

- Amine

- Ionic liquids

- Solid sorbents for carbon capture

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Arthur Kohl and Richard Nielson (1997). Gas Purification (5th ed.). Gulf Publishing. ISBN 0-88415-220-0.

- ↑ Gary, J.H. and Handwerk, G.E. (1984). Petroleum Refining Technology and Economics (2nd ed.). Marcel Dekker, Inc. ISBN 0-8247-7150-8.

- ↑ US 4080424, Loren N. Miller & Thomas S. Zawacki, "Process for acid gas removal from gaseous mixtures", issued 21 Mar 1978, assigned to Institute of Gas Technology

- ↑ Baker, R. W. "Future Directions of Membrane Gas Separation Technology" Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, volume 41, pages 1393-1411. doi:10.1021/ie0108088

- ↑ "Piperazine – Why It's Used and How It Works". The Contactor (Optimised Gas Treating, Inc.) 2 (4). 2008. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ↑ Sulfur production report by the United States Geological Survey

- ↑ Discussion of recovered byproduct sulfur

External links

- Description of Gas Sweetening Equipment and Operating Conditions

- Selecting Amines for Sweetening Units, Polasek, J. (Bryan Research & Engineering) and Bullin, J.A. (Texas A&M University), Gas Processors Association Regional Meeting, Sept. 1994.

- Natural Gas Supply Association Scroll down to Sulfur and Carbon Dioxide Removal

- Description of the classic book on gas treating by Arthur Kohl & Richard Nielsen. Gas Purification (Fifth ed.). Gulf Publishing. ISBN 0-88415-220-0.