Americas

.svg.png) | |

| Area | 42,549,000 km2 (16,428,000 mi2) |

|---|---|

| Population | 954 million (July 2013 estimate) [1] |

| Demonym | American,[2] New Worlder,[3] and Pan-American[4] are used (see usage) |

| Countries | 35 |

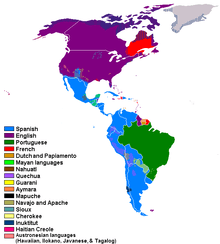

| Languages | English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Quechua, Haitian Creole, Guaraní, Aymara, Nahuatl, Dutch and many others |

| Time zones | UTC-10 to UTC |

| Largest cities | |

The Americas, or America,[5][6][7] also known as the New World, are the combined continental landmasses of North America and South America,[8][9] in the Western Hemisphere.[10] Along with their associated islands, they cover 8.3% of the Earth's total surface area (28.4% of its land area). The topography is dominated by the American Cordillera, a long chain of mountains that run the length of the west coast. The flatter eastern side of the Americas is dominated by large river basins, such as the Amazon, Mississippi, and La Plata. Since the Americas extend 14,000 km (8,700 mi) from north to south, the climate and ecology vary widely, from the arctic tundra of Northern Canada, Greenland, and Alaska, to the tropical rain forests in Central America and South America.

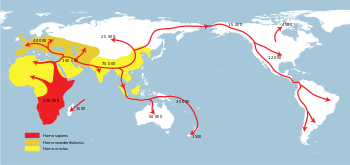

Humans first settled the Americas from Asia between 40,000 BCE and 15,000 BCE. A second migration of Na-Dene speakers followed later from Asia. The subsequent migration of the Inuit into the neoarctic around 3500 BCE completed what is generally regarded as the settlement by the indigenous peoples of the Americas. The first known European settlement in the Americas was by the Norse explorer Leif Ericson.[11] However the colonization never became permanent and was later abandoned. The voyages of Christopher Columbus from 1492 to 1502 resulted in permanent contact with European (and subsequently, other Old World) powers, which led to the Columbian exchange. Diseases introduced from Europe and Africa devastated the Indigenous peoples, and the European powers colonised the Americas.[12] Mass emigration from Europe, including large numbers of indentured servants, and forced immigration of African slaves largely replaced the Indigenous Peoples. Beginning with the American Revolution in 1776 and Haitian Revolution in 1791, the European powers began to decolonise the Americas. Currently, almost all of the population of the Americas resides in independent countries; however, the legacy of the colonisation and settlement by Europeans is that the Americas share many common cultural traits, most notably Christianity and the use of Indo-European languages; primarily Spanish, English, and Portuguese.

More than 900 million people live in the Americas, the most populous countries being the United States, Brazil, and Mexico, the most populous cities being São Paulo, Mexico City and New York City.

History

Settlement

The first inhabitants migrated into the Americas from Asia. Habitation sites are known in Alaska and the Yukon from at least 20 000 years ago, with suggested ages of up to 40,000 years.[14][15][16] Beyond that, the specifics of the Paleo-Indian migration to and throughout the Americas, including the dates and routes traveled, are subject to ongoing research and discussion.[17] Widespread habitation of the Americas occurred during the late glacial maximum, from 16,000 to 13,000 years ago.[16][18] The traditional theory has been that these early migrants moved into the Beringia land bridge between eastern Siberia and present-day Alaska around 40,000–17,000 years ago,[19] when sea levels were significantly lowered due to the Quaternary glaciation.[17][20] These people are believed to have followed herds of now-extinct pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.[21] Another route proposed is that, either on foot or using primitive boats, they migrated down the Pacific coast to South America.[22] Evidence of the latter would since have been covered by a sea level rise of hundreds of meters following the last ice age.[23] Both routes may have been taken, although the genetic evidences suggests a single founding population.[24] The micro-satellite diversity and distributions specific to South American Indigenous people indicates that certain populations have been isolated since the initial colonization of the region.[25]

A second migration occurred after the initial peopling of the Americas;[26] Na Dene speakers found predominantly in North American groups at varying genetic rates with the highest frequency found among the Athabaskans at 42% derive from this second wave;[27] Linguists and biologists have reached a similar conclusion based on analysis of Amerindian language groups and ABO blood group system distributions.[26][28][29][30] Then the people of the Arctic small tool tradition a broad cultural entity that developed along the Alaska Peninsula, around Bristol Bay, and on the eastern shores of the Bering Strait around 2,500 BCE (4,500 years ago) moved into North America.[31] The Arctic small tool tradition, a Paleo-Eskimo culture branched off into two cultural variants, including the Pre-Dorset, and the Independence traditions of Greenland.[32] The decedents of the Pre-Dorset cultural group, the Dorset culture was displaced by the final migrants from the Bering sea coast line the ancestors of modern Inuit, the Thule people by 1000 Common Era (CE).[32] Around the same time as the Inuit migrated into Greenland, Viking settlers began arriving in Greenland in 982 and Vinland shortly thereafter, establishing a settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows, near the northernmost tip of Newfoundland.[33] The Viking settlers quickly abandoned Vinland, and disappeared from Greenland by 1500.[34]

Pre-Columbian era

The pre-Columbian era incorporates all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original settlement in the Upper Paleolithic to European colonization during the Early Modern period. The term Pre-Columbian is used especially often in the context of the great indigenous civilizations of the Americas, such as those of Mesoamerica (the Olmec, the Toltec, the Teotihuacano, the Zapotec, the Mixtec, the Aztec, and the Maya) and the Andes (Inca, Moche, Muisca, Cañaris).

Many pre-Columbian civilizations established characteristics and hallmarks which included permanent or urban settlements, agriculture, civic and monumental architecture, and complex societal hierarchies. Some of these civilizations had long faded by the time of the first permanent European arrivals (c. late 15th–early 16th centuries), and are known only through archaeological investigations. Others were contemporary with this period, and are also known from historical accounts of the time. A few, such as the Maya, had their own written records. However, most Europeans of the time viewed such texts as pagan, and much was destroyed in Christian pyres. Only a few hidden documents remain today, leaving modern historians with glimpses of ancient culture and knowledge.[35]

European colonization

Although there had been previous trans-oceanic contact, large-scale European colonization of the Americas began with the first voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1492. The first Spanish settlement in the Americas was La Isabela in northern Hispaniola. This town was abandoned shortly after in favor of Santo Domingo de Guzmán, founded in 1496, the oldest American city of European foundation. This was the base from which the Spanish monarchy administered its new colonies and their expansion. On the continent, Panama City on the Pacific coast of Central America, founded on August 5, 1519, played an important role, being the base for the Spanish conquest of South America. The spread of new diseases brought by Europeans and Africans killed many of the inhabitants of North America and South America,[36][37] with a general population crash of Native Americans occurring in the mid-16th century, often well ahead of European contact.[38] European immigrants were often part of state-sponsored attempts to found colonies in the Americas. Migration continued as people moved to the Americas fleeing religious persecution or seeking economic opportunities. Millions of individuals were forcibly transported to the Americas as slaves, prisoners or indentured servants.

Decolonization of the Americas began with the American Revolution and the Haitian Revolution in the late 1700s. This was followed by numerous Latin American wars of independence in the early 1800s. Between 1811 and 1825, Paraguay, Argentina, Chile, Gran Colombia, the United Provinces of Central America, Mexico, Brazil, Peru, and Bolivia gained independence from Spain and Portugal in armed revolutions. After the Dominican Republic won independence from Haiti, it was re-annexed by Spain in 1861, but reclaimed its independence in 1865 at the conclusion of the Dominican Restoration War. The last violent episode of decolonisation was the Cuban War of Independence which became the Spanish–American War, which resulted in the independence of Cuba in 1898, and the transfer of sovereignty over Puerto Rico from Spain to the United States. Peaceful decolonisation began with the purchase by the United States of Louisiana from France in 1803, Florida from Spain in 1819, of Alaska from Russia in 1867, and the Danish West Indies from Denmark in 1916. Canada became independent of the United Kingdom, starting with the Balfour Declaration of 1926, Statute of Westminster 1931, and ending with the patriation of the Canadian Constitution in 1982. The Dominion of Newfoundland similarly achieved partial independence under the Balfour Declaration and Statute of Westminster, but was re-absorbed into the United Kingdom in 1934. It was subsequently confederated with Canada in 1949. Beginning with Jamaica in 1962, the remaining European colonies began to achieve peaceful independence. Trinidad and Tobago also became independent in 1962, and Guyana and Barbados both achieved independence in 1966. In the 1970s, the Bahamas, Grenada, Dominica, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines all became independent of the United Kingdom, and Suriname became independent of the Netherlands. Belize, Antigua and Barbuda, and Saint Kitts and Nevis achieved independence from the United Kingdom in the 1980s.

Etymology and naming

The earliest known use of the name America dates to April 25, 1507, where it was applied to what is now known as South America.[39] It appears on a small globe map with twelve time zones, together with the largest wall map made to date, both created by the German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller in Saint-Dié-des-Vosges in France.[40] These were the first maps to show the Americas as a land mass separate from Asia. An accompanying book, Cosmographiae Introductio, anonymous but apparently written by Waldseemüller's collaborator Matthias Ringmann,[41] states, "I do not see what right any one would have to object to calling this part [that is, the South American mainland], after Americus who discovered it and who is a man of intelligence, Amerigen, that is, the Land of Americus, or America: since both Europa and Asia got their names from women". Americus Vespucius is the Latinized version of the Florentine explorer Amerigo Vespucci's name, and America is the feminine form of Americus. Amerigo itself is an Italian form of the medieval Latin Emericus (see also Saint Emeric of Hungary), which like the German form Heinrich (in English, Henry) derives from the Old High German name Haimirich.[42]

Vespucci was apparently unaware of the use of his name to refer to the new landmass, as Waldseemüller's maps did not reach Spain until a few years after his death.[41] Ringmann may have been misled into crediting Vespucci by the widely published Soderini Letter, a sensationalized version of one of Vespucci's actual letters reporting on the mapping of the South American coast, which glamorized his discoveries and implied that he had recognized that South America was a continent separate from Asia; in fact, it is not known what Vespucci believed on this count, and he may have died believing, like Columbus, that he had reached the East Indies in Asia rather than a new continent.[43] Spain officially refused to accept the name America for two centuries, saying that Columbus should get credit, and Waldseemüller's later maps, after Ringmann's death, did not include it; however, usage was established when Gerardus Mercator applied the name to the entire New World in his 1538 world map. Acceptance may have been aided by the "natural poetic counterpart" that the name America made with Asia, Africa, and Europa.[41]

In modern English, North and South America are generally considered separate continents, and taken together are called the Americas in the plural, parallel to similar situations such as the Carolinas. When conceived as a unitary continent, the form is generally the continent of America in the singular. However, without a clarifying context, singular America commonly refers in English to the United States of America.[7]

Geography

Extent

The northernmost point of the Americas is Kaffeklubben Island, which is the most northerly point of land on Earth.[44] The southernmost point is the islands of Southern Thule, although they are sometimes considered part of Antarctica.[45] The mainland of the Americas is the world's longest north-to-south landmass. The distance between its two polar extremities, the Boothia Peninsula in northern Canada and Cape Froward in Chilean Patagonia, is roughly 14,000 km (8,700 mi).[46] The mainland's most westerly point is the end of the Seward Peninsula in Alaska; Attu Island, further off the Alaskan coast to the west, is considered the westernmost point of the Americas. Ponta do Seixas in northeastern Brazil forms the easternmost extremity of the mainland,[46] while Nordostrundingen, in Greenland, is the most easterly point of the continental shelf.

Geology

South America broke off from the west of the supercontinent Gondwana around 135 million years ago, forming its own continent.[47] Around 15 million years ago, the collision of the Caribbean Plate and the Pacific Plate resulted in the emergence of a series of volcanoes along the border that created a number of islands. The gaps in the archipelago of Central America filled in with material eroded off North America and South America, plus new land created by continued volcanism. By three million years ago, the continents of North America and South America were linked by the Isthmus of Panama, thereby forming the single landmass of the Americas.[48] The Great American Interchange resulted in many species being spread across the Americas, such as the cougar, porcupine, opossums, armadillos and hummingbirds.[49]

Topography

The geography of the western Americas is dominated by the American cordillera, with the Andes running along the west coast of South America[50] and the Rocky Mountains and other North American Cordillera ranges running along the western side of North America.[51] The 2,300-kilometer-long (1,400 mi) Appalachian Mountains run along the east coast of North America from Alabama to Newfoundland.[52] North of the Appalachians, the Arctic Cordillera runs along the eastern coast of Canada.[53]

The ranges with the highest peaks are the Andes and Rocky Mountain ranges. Although high peaks exist in the Sierra Nevada and the Cascade Range, on average there are not as many reaching a height greater than 14,000 feet. In North America, the greatest number of fourteeners are in the United States, and more specifically in the U.S. state of Colorado. The highest peaks of the Americas are located in the Andes, with Aconcagua of Argentina being the highest; in North America Mount McKinley (Denali) in the U.S. state of Alaska is the tallest.

Between its coastal mountain ranges, North America has vast flat areas. The Interior Plains spread over much of the continent, with low relief.[54] The Canadian Shield covers almost 5 million km² of North America and is generally quite flat.[55] Similarly, the north-east of South America is covered by the flat Amazon Basin.[56] The Brazilian Highlands on the east coast are fairly smooth but show some variations in landform, while farther south the Gran Chaco and Pampas are broad lowlands.[57]

Climate

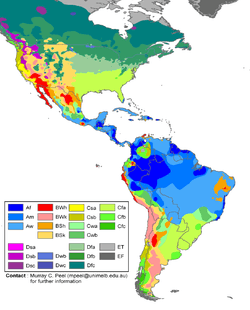

The climate of the Americas varies significantly from region to region. Tropical rainforest climate occurs in the latitudes of the Amazon, American cloud forests, Florida and Darien Gap. In the Rocky Mountains and Andes, a similar climate is observed. Often the higher altitudes of these mountains are snow-capped.

Southeastern North America is well known for its occurrence of tornadoes and hurricanes, of which the vast majority of tornadoes occur in the United States' Tornado Alley.[58] Often parts of the Caribbean are exposed to the violent effects of hurricanes. These weather systems are formed by the collision of dry, cool air from Canada and wet, warm air from the Atlantic.

Hydrology

With coastal mountains and interior plains, the Americas have several large river basins that drain the continents. The largest river basin in North America is that of the Mississippi, covering the second largest watershed on the planet.[59] The Mississippi-Missouri river system drains most of 31 states of the U.S., most of the Great Plains, and large areas between the Rocky and Appalachian mountains. This river is the fourth longest in the world and tenth most powerful in the world.

In North America, to the east of the Appalachian Mountains, there are no major rivers but rather a series of rivers and streams that flow east with their terminus in the Atlantic Ocean, such as the Hudson River, Saint John River, and Savannah River. A similar instance arises with central Canadian rivers that drain into Hudson Bay; the largest being the Churchill River. On the west coast of North America, the main rivers are the Colorado River, Columbia River, Yukon River, Fraser River, and Sacramento River.

The Colorado River drains much of the Southern Rockies and parts of the Great Basin and Range Province. The river flows approximately 1,450 miles (2,330 km) into the Gulf of California,[60] during which over time it has carved out natural phenomena such as the Grand Canyon and created phenomena such as the Salton Sea. The Columbia is a large river, 1,243 miles (2,000 km) long, in central western North America and is the most powerful river on the West Coast of the Americas. In the far northwest of North America, the Yukon drains much of the Alaskan peninsula and flows 1,980 miles (3,190 km)[61] from parts of Yukon and the Northwest Territory to the Pacific. Draining to the Arctic Ocean of Canada, the Mackenzie River drains waters from the Arctic Great Lakes of Arctic Canada, as opposed to the Saint-Laurence River that drains the Great Lakes of Southern Canada into the Atlantic Ocean. The Mackenzie River is the largest in Canada and drains 1,805,200 square kilometres (697,000 sq mi).[62]

The largest river basin in South America is that of the Amazon, which has the highest volume flow of any river on Earth.[63] The second largest watershed of South America is that of the Paraná River, which covers about 2.5 million km².[64]

Ecology

North America and South America began to developed a shared population of flora and fauna around 2.5 million years ago, when continental drift brought the two continents into contact via the Isthmus of Panama. Initially, the exchange of biota was roughly equal, with North American genera migrating into South America in about the same proportions as South American genera migrated into North America. This exchange is known as the Great American Interchange. The exchange became lopsided after roughly a million years, with the total spread of South American genera into North America far more limited in scope than the spread on North American genera into South America.[65]

Demography

Population

The total population of the Americas is about 951 million people and is divided as follows:

- North America: 565 million (includes Central America and the Caribbean)

- South America: 386 million

Largest urban centers

There are three urban centers that each hold titles for being the largest population area based on the three main demographic concepts:[66]

- A city proper is the locality with legally fixed boundaries and an administratively recognized urban status that is usually characterized by some form of local government.[67][68][69][70][71]

- An urban area is characterized by higher population density and vast human features in comparison to areas surrounding it. Urban areas may be cities, towns or conurbations, but the term is not commonly extended to rural settlements such as villages and hamlets. Urban areas are created and further developed by the process of urbanization and do not include large swaths of rural land, as do metropolitan areas.

- Unlike an urban area, a metropolitan area includes not only the urban area, but also satellite cities plus intervening rural land that is socio-economically connected to the urban core city, typically by employment ties through commuting, with the urban core city being the primary labor market.

In accordance with these definitions, the three largest population centers in the Americas are: Mexico City, anchor to the largest metropolitan area in the Americas; New York City, anchor to the largest urban area in the Americas; and São Paulo, the largest city proper in the Americas. All three cities maintain Alpha classification and large scale influence.

- Urban Centers within the Americas

-

São Paulo – Largest city proper in the Americas with a population of 10,886,534 in 2010.

-

New York City – Largest urban area in the Americas with a population of 18,351,295 in 2010.

-

Mexico City – Largest metropolitan area in the Americas with a population of 20,116,842 in 2010.

| Country | City | City Population | Metro Area Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico City | 8,864,000[72] | 20,116,842[73] | |

| New York City | 8,405,837[74] | 19,949,502[75] | |

| São Paulo | 11,821,876[76] | 19,889,559[76] |

Ethnology

The population of the Americas is made up of the descendants of four large ethnic groups and their combinations.

- The Indigenous peoples of the Americas, being Amerindians, Inuit, and Aleuts.

- Those of European ancestry, mainly Spanish, British and Irish, Portuguese, Italian, French, Polish, German, Dutch, Russians and Scandinavians.

- Those of African ancestry, mainly of West African descent.

- Asians, that is, those of Eastern, South, and Southeast Asian ancestry.

- Mestizos, those of mixed European and Amerindian ancestry.

- Metis people, those of mixed European and Native American/First Nations ethnic ancestry in the United States and Canada.

- Mulattoes, people of mixed African and European ancestry.

- Zambos (Spanish) or Cafusos (Portuguese), those of mixed African and Amerindian ancestry.

The majority of the population live in Latin America, named for its predominant cultures, rooted in Latin Europe (including the two dominant languages, Spanish and Portuguese, both Romance languages), more specifically in the Iberian nations of Portugal and Spain (hence the use of the term Ibero-America as a synonym). Latin America is typically contrasted with Anglo-America, where English, a Germanic language, is prevalent, and which comprises Canada (with the exception of francophone Canada rooted in Latin Europe [France]—see Québec and Acadia) and the United States. Both countries are located in North America, with cultures deriving predominantly from Anglo-Saxon and other Germanic roots.

Religion

The most prevalent faiths in the Americas are as follows:

- Christianity (86 percent)[77]

- Roman Catholicism: Practiced by 69 percent[78] of the Latin American population, 81 percent[78] in Mexico and 61 Percent[78] in Brazil whose Roman Catholic population of 123 million is the greatest of any nation's; approximately 24 percent of the United States' population[79] and about 39 percent of Canada's.[80]

- Protestantism: Practiced mostly in the United States, where half of the population are Protestant, and Canada, with slightly more than a quarter of the population; there is a growing contingent of Evangelical and Pentecostal movements in predominantly Catholic Latin America.[81]

- Eastern Orthodoxy: Found mostly in the United States (1 percent)and Canada; this Christian group is growing faster than many other Christian groups in Canada and now represents roughly 3 percent of the Canadian population.[80]

- Non-denominational Christians and other Christians (some 1,000 different Christian denominations and sects practiced in the Americas

- Irreligion: About 12 Percent, including atheists and agnostics, as well as those who profess some form of spirituality but do not identify themselves as members of any organized religion)

- Islam: Together, Muslims constitute about 1 percent of the North American population and 0.3 percent of all Latin Americans. It is practiced by 3 percent [80] of Canadians and 0.6 percent of the U.S. population.[79] Argentina has the largest Muslim population in Latin America with up to 600,000 persons, or 1.9 percent of the population.[82]

- Judaism (practiced by 2 percent of North Americans—approximately 2.5 percent of the U.S. population and 1.2 percent of Canadians[83]—and 0.23 percent of Latin Americans—Argentina has the largest Jewish population in Latin America with 200,000 members)[84]

Other faiths include Buddhism; Hinduism; Sikhism; Bahá'í Faith; a wide variety of indigenous religions, many of which can be categorized as animistic; new age religions and many African and African-derived religions. Syncretic faiths can also be found throughout the Americas.

Languages

Various languages are spoken in the Americas. Some are of European origin, others are spoken by indigenous peoples or are the mixture of various idioms like the different creoles.

The most widely spoken language in the Americas is Spanish. The dominant language of Latin America is Spanish, though the most populous nation in Latin America, Brazil, speaks Portuguese. Small enclaves of French-, Dutch- and English-speaking regions also exist in Latin America, notably in French Guiana, Suriname, and Belize and Guyana respectively, and Haitian Creole, of French origin, is dominant in the nation of Haiti. Native languages are more prominent in Latin America than in Anglo-America, with Nahuatl, Quechua, Aymara and Guaraní as the most common. Various other native languages are spoken with less frequency across both Anglo-America and Latin America. Creole languages other than Haitian Creole are also spoken in parts of Latin America.

The dominant language of Anglo-America is English. French is also official in Canada, where it is the predominant language in Quebec and an official language in New Brunswick along with English. It is also an important language in Louisiana, and in parts of New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont. Spanish has kept an ongoing presence in the Southwestern United States, which formed part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, especially in California and New Mexico, where a distinct variety of Spanish spoken since the 17th century has survived. It has more recently become widely spoken in other parts of the United States due to heavy immigration from Latin America. High levels of immigration in general have brought great linguistic diversity to Anglo-America, with over 300 languages known to be spoken in the United States alone, but most languages are spoken only in small enclaves and by relatively small immigrant groups.

The nations of Guyana, Suriname, and Belize are generally considered not to fall into either Anglo-America or Latin America due to lingual differences with Latin America, geographic differences with Anglo-America, and cultural and historical differences with both regions; English is the primary language of Guyana and Belize, and Dutch is the official and written language of Suriname.

Most of the non-native languages have, to different degrees, evolved differently from the mother country, but are usually still mutually intelligible. Some have combined, however, which has even resulted in completely new languages, such as Papiamento, which is a combination of Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch (representing the respective colonizers), native Arawak, various African languages, and, more recently English. The lingua franca Portuñol, a mixture of Portuguese and Spanish, is spoken in the border regions of Brazil and neighboring Spanish-speaking countries.[85] More specifically, Riverense Portuñol is spoken by around 100,000 people in the border regions of Brazil and Uruguay. Due to immigration, there are many communities where other languages are spoken from all parts of the world, especially in the United States, Brazil, Argentina, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica and Uruguay—very important destinations for immigrants.[86][87][88]

Terminology

| Subdivisions of the Americas | |

|---|---|

| Map | Legend |

|

North America (NA)

South America (SA)

May be included in either NA or SA |

|

North America (NA)

May be included in NA

Central America

Caribbean

South America |

|

North America (NA)

May be included in NA

Northern America Middle America (MA)

Caribbean (may be

included in MA) South America (SA)

May be included in MA or SA |

|

Anglo-America (A-A)

May be included in A-A

Latin America (LA)

May be included in LA |

English

Speakers of English generally refer to the landmasses of North America and South America as the Americas, the Western Hemisphere, or the New World.[89] The adjective American may be used to indicate something pertains to the Americas,[2] but this term is primarily used in English to indicate something pertaining to the United States.[2][90][91] Some non-ambiguous alternatives exist, such as the adjective Pan-American,[92] or New Worlder as a demonym for a resident of the Americas.[3] Use of America in the hemispherical sense is sometimes retained, or can occur when translated from other languages.[93] For example, the Association of National Olympic Committees (ANOC) in Paris maintains a single continental association for "America", represented by one of the five Olympic rings.[94]

The English-language use of "American" as the demonym for citizens of the United States has caused offense to some from Latin America[95] who may identify themselves with the term "American" and feel that using the term solely for the United States misappropriates it.[96] To avoid this usage, they prefer constructed terms in their languages derived from "United States" or even "North America".[91][97][98] In Canada, its southern neighbor is often referred to as "the United States", "the U.S.A.", or (informally) "the States," while citizens are generally referred to as Americans.[91] Most Canadians resent being referred to as Americans,[91] but some are said to have protested the use of American as a national demonym.[91][99]

Spanish

In Spanish, América is a single continent composed of the subcontinents of Sudamérica and Norteamérica, the land bridge of Centroamérica, and the islands of the Antillas. Americano or americana in Spanish refers to a person from América in a similar way that europeo or europea refers to a person from Europa. The terms sudamericano/a, centroamericano/a, antillano/a and norteamericano/a can be used to more specifically refer to the location where a person may live.

Citizens of the United States of America are normally referred to by the term estadounidense (rough literal translation: "United Statesian") instead of americano or americana which is discouraged,[100][101] and the country's name itself is officially translated as Estados Unidos de América (United States of America), commonly abbreviated as Estados Unidos.[101] Also, the term norteamericano (North American) may refer to a citizen of the United States. This term is primarily used to refer to citizens of the United States, and less commonly to those of other North American countries.[100]

Portuguese

In Portuguese, América[102] is a single continent composed of América do Sul (South America), América Central (Central America) and América do Norte (North America).[103] It can be ambiguous, as América can be used to refer to the United States of America, but is avoided in print and formal environments.[104][105]

French

In French the word américain may be used for things relating to the Americas, however, similar to English, it is most often used for things relating to the United States. Panaméricain may be used as an adjective to refer to the Americas without ambiguity.[106] French speakers may use the noun Amérique to refer to the whole landmass as one continent, or two continents, Amérique du Nord and Amérique du Sud. In French, Amérique is also used to refer to the United States, making the term ambiguous. Similar to English usage, les Amériques or des Amériques is used to refer unambiguously to the Americas.

Dutch

In Dutch, the word Amerika mostly refers to the United States. Although the United States is equally often referred to as de Verenigde Staten or de VS, Amerika relatively rarely refers to the Americas, but it is the only commonly used Dutch word for the Americas. This often leads to ambiguity; and to stress that something concerns the Americas as a whole, Dutch uses a combination, namely Noord- en Zuid-Amerika (North and South America).

Latin America is generally referred to as Latijns Amerika or Midden-Amerika for Central America.

The adjective Amerikaans is most often used for things or people relating to the United States. There are no alternative words to distinguish between things relating to the United States or to the Americas. Dutch uses the local alternative for things relating to elsewhere in the Americas, such as Argentijns for Argentine, etc.

Politics

Countries and territories

There are 35 sovereign states in the Americas, as well as an autonomous country of Denmark, three overseas departments of France, three overseas collectivities of France,[107] and one uninhabited territory of France, eight overseas territories of the United Kingdom, three constituent countries of the Netherlands, three public bodies of the Netherlands, two unincorporated territories of the United States, and one uninhabited territory of the United States.[108]

| Country or territory | Area (km²)[109] |

Population[note 1] | Population density (per km²) |

Languages (official in bold) | Capital | Gross Domestic Product (Purchasing Power Parity) USD [1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

91 | 13,452 | 164.8 | English | The Valley | $175,400,000 |

| |

442 | 86,295 | 199.1 | Creole,[110] English | St. John's | $1,605,000,000 |

| |

2,766,890 | 42,669,500 | 14.3 | Spanish | Buenos Aires | $777,900,000,000 |

| |

180 | 101,484 | 594.4 | Papiamentu, Spanish,[111] Dutch | Oranjestad | $2,516,000,000 |

| |

13,943 | 351,461 | 24.5 | Creole,[112] English | Nassau | $11,240,000,000 |

| |

430 | 285,000 | 595.3 | Bajan,[113] English | Bridgetown | $7,169,000,000 |

| |

22,966 | 349,728 | 13.4 | Spanish, Kriol, English[114] | Belmopan | $3,048,000,000 |

| |

54 | 64,237 | 1,203.7 | English | Hamilton | $5,600,000,000 |

| |

1,098,580 | 10,027,254 | 8.4 | Spanish, Quechua, Aymara, 35 additional indigenous languages | La Paz and Sucre [115] | $56,140,000,000 |

| |

294 | 12,093 | 41.1 | Papiamentu, Spanish, Dutch[116] | Kralendijk | |

| |

8,514,877 | 203,106,000 | 23.6 | Portuguese | Brasília | $2,423,000,000,000 |

| |

151 | 29,537 | 152.3 | English | Road Town | $500,000,000 |

| |

9,984,670 | 35,427,524 | 3.4 | English, French | Ottawa | $1,526,000,000,000 |

| |

264 | 55,456 | 212.1 | English | George Town | $2,250,000,000 |

| |

756,950 | 17,773,000 | 22 | Spanish | Santiago | $334,800,000,000 |

| |

6[118] | 0[119] | 0.0 | No | — | $0 |

| |

1,138,910 | 47,757,000 | 40 | Spanish | Bogotá | $527,600,000,000 |

| |

51,100 | 4,667,096 | 89.6 | Spanish | San José | $45,130,000,000 |

| |

109,886 | 11,167,325 | 102.0 | Spanish | Havana | $121,000,000,000 |

| |

444 | 150,563 | 317.1 | Papiamentu, Dutch[116] | Willemstad | $2,838,000,000 |

| |

751 | 71,293 | 89.2 | French Patois, English[120] | Roseau | $1,018,000,000 |

| |

48,671 | 10,378,267 | 207.3 | Spanish | Santo Domingo | $100,400,000,000 |

| |

283,560 | 15,819,400 | 53.8 | Spanish, Quechua[121] | Quito | $159,000,000,000 |

| |

21,041 | 6,401,240 | 293.0 | Spanish | San Salvador | $47,090,000,000 |

| |

12,173 | 3,000 | 0.26 | English | Port Stanley | $164,500,000 |

| |

91,000 | 237,549 | 2.7 | French | Cayenne | |

| |

2,166,086 | 56,483 | 0.026 | Greenlandic, Danish | Nuuk (Godthåb) | $2,133,000,000 |

| |

344 | 103,328 | 302.3 | English | St. George's | $1,467,000,000 |

| |

1,628 | 405,739 | 246.7 | French | Basse-Terre | |

| |

108,889 | 15,806,675 | 128.8 | Spanish, Garifuna and 23 Mayan languages | Guatemala City | $79,970,000,000 |

| |

214,999 | 784,894 | 3.5 | English | Georgetown | $6,256,000,000 |

| |

27,750 | 10,745,665 | 361.5 | Creole, French | Port-au-Prince | $13,150,000,000 |

| |

112,492 | 8,555,072 | 66.4 | Spanish | Tegucigalpa | $38,420,000,000 |

| |

10,991 | 2,717,991 | 247.4 | Patois, English | Kingston | $25,620,000,000 |

| |

1,128 | 392,291 | 352.6 | Patois,[123] French | Fort-de-France | |

| |

1,964,375 | 119,713,203 | 57.1 | Spanish, 68 indigenous languages | Mexico City | $1,843,000,000,000 |

| |

102 | 4,922 | 58.8 | Creole English, English[124] | Plymouth; Brades[125] | $43,780,000 |

| |

5[118] | 0[119] | 0.0 | No | — | $0 |

| |

130,373 | 6,071,045 | 44.1 | Spanish | Managua | $27,100,000,000 |

| |

75,417 | 3,405,813 | 45.8 | Spanish | Panama City | $58,020,000,000 |

| |

406,750 | 6,783,374 | 15.6 | Guaraní, Spanish | Asunción | $41,550,000,000 |

| |

1,285,220 | 30,814,175 | 22 | Spanish, Quechua, Aymara | Lima | $344,200,000,000 |

| |

8,870 | 3,615,086 | 448.9 | Spanish, English | San Juan | $127,000,000,000 |

| |

13 | 1,537[126] | 118.2 | English, Dutch | The Bottom | |

| |

21[118] | 8,938[119] | 354.7 | French | Gustavia | |

| |

261 | 55,000 | 199.2 | English | Basseterre | $946,300,000 |

| |

539 | 180,000 | 319.1 | English, French Creole | Castries | $2,233,000,000 |

| |

54[118] | 36,979 | 552.2 | French | Marigot | $561,500,000 |

| |

242 | 6,081 | 24.8 | French | Saint-Pierre | $215,300,000 |

| |

389 | 109,000 | 280.2 | English | Kingstown | $1,312,000,000 |

| |

21 | 2,739[126] | 130.4 | Dutch, English | Oranjestad | |

| |

34 | 37,429 | 1,176.7 | English, Spanish, Dutch | Philipsburg | $798,300,000 |

| South Sandwich Islands (United Kingdom)[127] |

3,093 | 20 | 0.01 | English | Grytviken | |

| |

163,270 | 534,189 | 3 | Dutch, Hindi-Urdu, Srana, Javanese, English Creole[128] | Paramaribo | $6,874,000,000 |

| |

5,130 | 1,328,019 | 261.0 | English | Port of Spain | $27,140,000,000 |

| |

948 | 31,458 | 34.8 | Creole English, English[129] | Cockburn Town | $632,000,000 |

| |

9,629,091 | 320,206,000 | 34.2 | English, Spanish | Washington, D.C. | $16,800,000,000,000 |

| |

347 | 106,405 | 317.0 | English, Spanish | Charlotte Amalie | |

| |

176,220 | 3,286,314 | 19.4 | Spanish | Montevideo | $54,670,000,000 |

| |

916,445 | 30,206,307 | 30.2 | Spanish and 40 indigenous languages | Caracas | $407,900,000,000 |

| Total | 42,320,985 | 953,700,000 | 21.9 | $24,864,000,000,000 |

Multinational organizations in the Americas

- Alliance for Progress

- American Capital of Culture

- Andean Community of Nations

- Association of Caribbean States

- Bank of the South

- Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas

- Caribbean Community

- CARICOM Single Market and Economy

- Central American Common Market

- Central American Parliament

- Community of Latin American and Caribbean States

- Contadora Group

- Free Trade Area of the Americas

- Latin American Free Trade Agreement

- Latin American Parliament or (Parlatino)

- List of Parliamentary Speakers in the Americas in 1984

- Mercosur or Mercosul

- North American Free Trade Agreement

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization

- Organization of American States

- Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

- Organization of Ibero-American States

- Pan American Sports Organization

- Regional Security System

- Rio Group

- School of the Americas

- Summit of the Americas

- Union of South American Nations

- YOA Orchestra of the Americas

See also

- Amerrique Mountains

- British North America

- Columbia (name)

- Conquistadors

- Ethnic groups in Central America

- List of former sovereign states

- French America

- La Merika

- List of conflicts in the Americas

- List of countries in the Americas by population

- Middle America (Americas)

- Monarchies in the Americas

- New Sweden

- Northern America

- Paleo-Indians

- Pan-Americanism

- Southern Cone

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "American". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "New Worlder". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005.

- ↑ "Pan-American - definition of Pan-American by The Free Dictionary". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ↑ See for example: america – Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved on January 27, 2008; "dictionary.reference.com america". Dictionary.com. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. Accessed: January 27, 2008.

- ↑ Marjorie Fee and Janice MacAlpine, Oxford Guide to Canadian English Usage (2008) page 36 says "In Canada, American is used almost exclusively in reference to the United States and its citizens." Others, including The New Zealand Oxford Dictionary, The Canadian Oxford Dictionary, The Australian Oxford Dictionary and The Concise Oxford English Dictionary all specify both the Americas and the United States in their definition of "American".

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "America." The Oxford Companion to the English Language (ISBN 0-19-214183-X). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 33: "[16c: from the feminine of Americus, the Latinized first name of the explorer Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512). The name America first appeared on a map in 1507 by the German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller, referring to the area now called Brazil]. Since the 16c, a name of the western hemisphere, often in the plural Americas and more or less synonymous with the New World. Since the 18c, a name of the United States of America. The second sense is now primary in English: ... However, the term is open to uncertainties: ..."

- ↑ Webster's New World College Dictionary, 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio.

- ↑ Merriam Webster dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. 2013.

- ↑ "continent n. 5. a." (1989) Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition. Oxford University Press ; "continent1 n." (2006) The Concise Oxford English Dictionary, 11th edition revised. (Ed.) Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson. Oxford University Press; "continent1 n." (2005) The New Oxford American Dictionary, 2nd edition. (Ed.) Erin McKean. Oxford University Press; "continent [2, n] 4 a" (1996) Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged. ProQuest Information and Learning ; "continent" (2007) Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 14 January 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ "Leif Erikson (11th century)". BBC. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ↑ [examiner.com/article/apocalypic-mysterious-plague-killed-millions-of-native-americans-the-1500s Examiner, 2012]

- ↑ Burenhult, Göran (2000). Die ersten Menschen. Weltbild Verlag. ISBN 3-8289-0741-5.

- ↑ "Introduction". Government of Canada. Parks Canada. 2009. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

Canada's oldest known home is a cave in Yukon occupied not 12,000 years ago like the U.S. sites, but at least 20,000 years ago

- ↑ "Pleistocene Archaeology of the Old Crow Flats". Vuntut National Park of Canada. 2008. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

However, despite the lack of this conclusive and widespread evidence, there are suggestions of human occupation in the northern Yukon about 24,000 years ago, and hints of the presence of humans in the Old Crow Basin as far back as about 40,000 years ago.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Jorney of mankind". Brad Shaw Foundation. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Atlas of the Human Journey-The Genographic Project". National Geographic Society. 1996–2008. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ↑ Bonatto, SL; Salzano, FM (1997). "A single and early migration for the peopling of the Americas supported by mitochondrial DNA sequence data". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (National Academy of Sciences) 94 (5): 1866–71. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.5.1866. PMC 20009. PMID 9050871.

- ↑ Wells, Spencer; Read, Mark (2002). The Journey of Man – A Genetic Odyssey (DIGITISED ONLINE BY GOOGLE BOOKS). Random House. pp. 138–140. ISBN 0-8129-7146-9. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ↑ Fitzhugh, Drs. William; Goddard, Ives; Ousley, Steve; Owsley, Doug; Stanford, Dennis. "Paleoamerican". Smithsonian Institution Anthropology Outreach Office. Archived from the original on January 5, 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ↑ "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". Scientific American. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ↑ Fladmark, K. R. (1979). "Alternate Migration Corridors for Early Man in North America". American Antiquity, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Jan., 1979), p2 44 (1): 55–69. doi:10.2307/279189. JSTOR 279189.

- ↑ "68 Responses to "Sea will rise 'to levels of last Ice Age'"". Center for Climate Systems Research, Columbia University. Archived from the original on October 27, 2009. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ↑ Ledford, Heidi (8 January 2009). "Earliest Americans took two paths". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2009.7.

- ↑ "Summary of knowledge on the subclades of Haplogroup Q". Genebase Systems. 2009. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 David J. Meltzer (27 May 2009). First Peoples in a New World: Colonizing Ice Age America. University of California Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-520-25052-9.

- ↑ Reich et al. (16 August 2012). "Reconstructing Native American population history" 488 (7411). Nature. pp. 370–374.

- ↑ Lyovi, Anatole (1997). An introduction to the languages of the world. Oxford University Press. p. 309. ISBN 0-19-508115-3. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ↑ Mithun, Marianne (1990). "Studies of North American Indian Languages". Annual Review of Anthropology 19 (1): 309–330. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.19.100190.001521.

- ↑ Vajda, Edward (2010). "A Siberian link with Na-Dene languages" 5. Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska.

- ↑ Fagan, Brian M. (2005). Ancient North America: The Archaeology of a Continent. (4 ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson Inc. pp. 390, p396. ISBN 0-500-28148-3.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 T. Kue Young; Peter Bjerregaard (28 June 2008). Health Transitions in Arctic Populations. University of Toronto Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-8020-9401-8.

- ↑ "Vinland". Canadian Museum of Civilization.

- ↑ "The Norse settlers in Greenland – A short history". Greenland Guide – The Official Travel Index.

- ↑ Mann, Charles C. (2005). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-1-4000-4006-3. OCLC 56632601.

- ↑ Russell Thornton (1997). "Aboriginal North American Population and Rates of Decline, c.a. A.D. 1500–1900". Current Anthropology 38 (2): 310–315. doi:10.1086/204615. JSTOR 00113204.

- ↑ Alfred W. Crosby (April 1976). "Virgin Soil Epidemics as a Factor in the Aboriginal Depopulation in America". David and Mary Quarterly 33 (2): 289–299. JSTOR 1922166.

- ↑ Henry F. Dobyns (1993). "Disease Transfer at Contact". Annual Review of Anthropology 22 (22): 273–291. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.22.100193.001421. JSTOR 2155849.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholomaei traditionem et Americi Vespucii alioru[m]que lustrationes.". Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ↑ Martin Waldseemüller. "Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholomaei traditionem et Americi Vespucii alioru[m]que lustrationes.". Washington, DC: Library of Congress. LCCN 2003626426. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Toby Lester, December (2009). "Putting America on the Map". Smithsonian 40: 9.

- ↑ "Amerigo – meaning of Amerigo name". Thinkbabynames.com. Archived from the original on July 12, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ↑ "UK | Magazine | The map that changed the world". BBC News. October 28, 2009. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ↑ Charles Burress (June 17, 2004). "Romancing the north Berkeley explorer may have stepped on ancient Thule". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ "South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, Antarctica – Travel".

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "America". The World Book Encyclopedia 1. World Book, Inc. 2006. p. 407. ISBN 0-7166-0106-0.

- ↑ Brian C. Story (September 28, 1995). "The role of mantle plumes in continental breakup: case histories from Gondwanaland". Nature 377 (6547): 301–309. doi:10.1038/377301a0.

- ↑ "Land bridge: How did the formation of a sliver of land result in major changes in biodiversity". Public Broadcasting Corporation.

- ↑ "Panama: Isthmus that Changed the World". NASA Earth Observatory. Retrieved July 1, 2008.

- ↑ "Andes Mountain Range". Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Rocky Mountains".

- ↑ "Appalachian Mountains". Ohio History Central.

- ↑ Arctic Cordillera

- ↑ "Interior Plains Region". Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Natural History of Quebec". Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Strategy". Amazon Conservation Association.

- ↑ "South America images". Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ↑ Sid Perkins (May 11, 2002). "Tornado Alley, USA". Science News. pp. 296–298. Archived from the original on August 25, 2006. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ↑ "Mississippi River".

- ↑ Kammerer, J.C. "Largest Rivers in the United States". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ↑ "Yukoninfo.com". Yukoninfo.com. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Mackenzie River". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Greatest Places: Notes: Amazonia".

- ↑ "Great Rivers Partnership – Paraguay-Parana".

- ↑ Webb, S. David (1991). "Ecogeography and the Great American Interchange". Paleobiology (Paleontological Society) 17 (3). JSTOR 2400869.

- ↑ David E. Bloom, David Canning, Günther Fink, Tarun Khanna, Patrick Salyer. "Urban Settlement" (PDF). Working Paper No. 2010/12. Helsinki: World Institute for Development Economics Research. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ↑ klaus kästle (August 31, 2009). "United States most populated cities". Nationsonline.org. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ↑ "World Urbanization Prospects: The 2007 Revision Population Database". United Nations. Archived from the original on August 22, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ↑ "United Nations Statistics Division – Demographic and Social Statistics". Millenniumindicators.un.org. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ↑ Demographic Yearbook 2005, Volume 57. United Nations. 2008. p. 756. ISBN 92-1-051099-2. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ↑ United Nations. Dept. of Economic and Social Affairs (2002). Demographic yearbook, 2000. United Nations Publications, 2002. p. 23. ISBN 92-1-051091-7.

- ↑ "Mexico City Population 2013". World Population Statistics. World Population Statistics. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Mexico City Population 2014". World Population Review. World Population Review. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- ↑ "New York City Population Hits Record High". The Wall Street Journal. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2013 - United States -- Metropolitan Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico". Census Bureau. Census Bureau. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 "Sao Paulo Population 2013". World Population Statistics. World Population Statistics. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Global Christianity". Pew.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 "2014 Religion in Latin America". Retrieved November 1 16, 2014. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 79.0 79.1 "United States". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. November 16, 2010. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 "Religions in Canada—Census 2011". Statistics Canada/Statistique Canada.

- ↑ "The World Today – Catholics faced with rise in Protestantism". Australia: ABC. April 19, 2005. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- ↑ "Argentina". International Religious Freedom Report. U.S. Department of State. 2006. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ↑ "Canadian Jewry Today: Portrait of a Community in the Process of Change – Ira Robinson". Jcpa.org. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- ↑ Naomi Segal. "First Planeload of Jews Fleeing Argentina Arrives in Israel". Ujc.org. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- ↑ Lipski, John M. (2006). Timothy L. Face; Carol A. Klee), eds. "Too Close for Comfort? The Genesis of "Portuñol/Portunhol"". Selected Proceedings of the 8th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium: 1–22. ISBN 978-1-57473-408-9. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ↑ Juan Bialet Massé en su informe sobre "El estado de las clases obreras en el interior del país"

- ↑ SOCIAL IDENTITY Marta Fierro Social Psychologist.

- ↑ Etnicidad y ciudadanía en América Latina.

- ↑ Burchfield, R. W. 2004. Fowler's Modern English Usage. (ISBN 0-19-861021-1) Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; p. 48.

- ↑ Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. "American Heritage Dictionary Entry: american". Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 91.2 91.3 91.4 "America." Oxford Guide to Canadian English Usage. (ISBN 0-19-541619-8) Fee, Margery and McAlpine, J., ed., 1997. Toronto: Oxford University Press; p. 36.

- ↑ Pan-American - Definition from the Merriam Webster dictionary.

- ↑ Reader's Digest Oxford Complete Wordfinder. 1993. (ISBN 0-276-42101-9) New York, USA: Reader's Digest Association; p. 45.

- ↑ The Olympic symbols. International Olympic Committee. 2002. Lausanne: Olympic Museum and Studies Centre. The five rings of the Olympic flag represent the five inhabited, participating continents: (Africa, America, Asia, Europe, and Oceania).

- ↑ "America." Microsoft Encarta Dictionary. 2007. Microsoft. Archived October 31, 2009.

- ↑ Mencken, H. L. (December 1947). "Names for Americans". American Speech (American Speech) 22 (4): 241–256. doi:10.2307/486658. JSTOR 486658.

- ↑ "American." The Oxford Companion to the English Language (ISBN 0-19-214183-X); McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 35.

- ↑ "Estados Unidos". Diccionario panhispánico de dudas (in Spanish). Real Academia Española. October 2005. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ↑ de Ford, Miriam Allen (April 1927). "On the difficulty of indicating nativity in the United States". American Speech: 315.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Diccionario panhispánico de dudas:Norteamérica. Real Academia Española. 2005.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Diccionario panhispánico de dudas: Estados Unidos. Real Academia Española. 2005. "debe evitarse el empleo de americano para referirse exclusivamente a los habitantes de los Estados Unidos" ("the use of the term americano referring exclusively to the United States inhabitants must be avoided")

- ↑ "Países da América". Brasil Escola. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ↑ "América". Mundo Educação. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Estados Unidos". Itamaraty. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Estados Unidos". ESPN. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ↑ "panaméricain". Office québéqois de la langue français. 1978. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Les Collectivités". Ministère des Outre-Mer. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 20 September 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ↑ Unless otherwise noted, land area figures are taken from "Demographic Yearbook—Table 3: Population by sex, rate of population increase, surface area and density" (PDF). United Nations Statistics Division. 2008. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- ↑ Sara Louise Kras (2008). Antigua and Barbuda. Marshall Cavendish. p. 95. ISBN 0-7614-2570-5.

- ↑ "Aruba Census 2010 Languages spoken in the household". Central Bureau of Statistics.

- ↑ Paul M. Lewis (2009). "Languages of Bahamas". Dallas: Ethnologue.

- ↑ Paul M. Lewis, ed. (2009). "Languages of Barbados". Dallas: Ethnologue: Languages of the World.

- ↑ "Belize 2000 Housing and Population Census". Belize Central Statistical Office. 2000. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- ↑ La Paz is the administrative capital of Bolivia;

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 "Households by the most spoken language in the household Population and Housing Census 2001". Central Bureau of Statistics.

- ↑ Includes Easter Island in the Pacific Ocean, a Chilean territory frequently reckoned in Oceania. Santiago is the administrative capital of Chile; Valparaíso is the site of legislative meetings.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 118.2 118.3 Land area figures taken from "The World Factbook: 2010 edition". Government of the United States, Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 119.2 These population estimates are for 2010, and are taken from "The World Factbook: 2010 edition". Government of the United States, Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ↑ Paul M. Lewis, M. Paul, ed. (2009). "Languages of Dominica". Dallas: Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ↑ David Levinson (1998). Ethnic Groups Worldwide: A Ready Reference Handbook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 347. ISBN 1-57356-019-7.

- ↑ Claimed by Argentina.

- ↑ Paul M. Lewis, ed. (2009). "Languages of Martinique". Dallas: Ethnologue.

- ↑ Paul M. Lewis, ed. (2009). "Languages of Montserrat". Dallas: Ethnologue.

- ↑ Due to ongoing activity of the Soufriere Hills volcano beginning in July 1995, much of Plymouth was destroyed and government offices were relocated to Brades. Plymouth remains the de jure capital.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 Population estimates are taken from the Central Bureau of Statistics Netherlands Antilles. "Statistical information: Population". Government of the Netherlands Antilles. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ↑ Claimed by Argentina; the South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean are commonly associated with Antarctica (due to proximity) and have no permanent population, only hosting a periodic contingent of about 100 researchers and visitors.

- ↑ Lewis, Paul (2009). "Languages of Suriname". Dallas, Texas: Ethnologue.

- ↑ Lewis, M. Paul (2009). "Languages of Turks and Caicos Islands". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas: SIL International.

Further reading

- "Americas". The Columbia Gazetteer of the World Online. 2006. New York: Columbia University Press.

- "Americas". Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th ed. 1986. (ISBN 0-85229-434-4) Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- Burchfield, R. W. 2004. Fowler's Modern English Usage. ISBN 0-19-861021-1 Oxford University Press.

- Churchill, Ward A Little Matter of Genocide 1997 City Lights Books ISBN 0-87286-323-9

- Fee, Margery and McAlpine, J. 1997. Oxford Guide to Canadian English Usage. (ISBN 0-19-541619-8) Toronto: Oxford University Press.

- Kane, Katie Nits Make Lice: Drogheda, Sand Creek, and the Poetics of Colonial Extermination Cultural Critique, No. 42 (Spring, 1999), pp. 81–103 doi:10.2307/1354592

- Pearsall, Judy and Trumble, Bill., ed. 2002. Oxford English Reference Dictionary, 2nd ed. (rev.) (ISBN 0-19-860652-4) Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- What's the difference between North, Latin, Central, Middle, South, Spanish and Anglo America? Geography at about.com.

External links

| Look up americas in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Media related to America at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to America at Wikimedia Commons- United Nations population data by latest available Census: 2008–2009

- Organization of American States

- Council on Hemispheric Affairs

-

Henry Gannett, Ernest Ingersoll, George Parker Winship and others (1905). "America". New International Encyclopedia.

Henry Gannett, Ernest Ingersoll, George Parker Winship and others (1905). "America". New International Encyclopedia.

Coordinates: 19°N 96°W / 19°N 96°W

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)