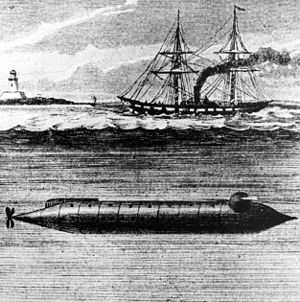

American submarine Alligator (1862)

Contemporary artist's rendering of Alligator | |

| Career (United States of America) | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Alligator |

| Namesake: | Alligator mississippiensis |

| Ordered: | 1 November 1861 |

| Builder: | Neafie & Levy |

| Launched: | 1 May 1862 |

| In service: | 13 June 1862 |

| Fate: | Foundered 2 April 1863 |

| Status: | Lost |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 275 tons surface, 350 tons submerged |

| Length: | 47 ft (14 m) |

| Beam: | 4 ft 6 in (1.37 m) (excluding oars); height of hull 6 ft (1.8 m) |

| Propulsion: | 1862: 16 × hand-powered oars 1863: Hand-cranked propeller |

| Speed: | 1862: 2 knots (3.7 km/h); 1863: 4 knots (7.4 km/h) |

| Test depth: | 6.8 ft (2.1 m) |

| Complement: | 12 - One officer, one helmsman, one or two divers, and 8 oarsmen |

| Armament: | 2 × limpet mines |

The USS Alligator, the fourth United States Navy ship of that name, is the first known U.S. Navy submarine, and was active during the American Civil War. The first American submarine, built in the Revolutionary War era, was the Turtle; however, the U.S. Navy did not exist when this craft was operational.

Construction

In the autumn of 1861, the Navy asked the firm of Neafie & Levy to construct a small submersible ship designed by the French engineer Brutus de Villeroi, who also acted as a supervisor during the first phase of the construction.

The ship was about 30 ft (9 m) long and 6 ft (1.8 m) or 8 ft (2.4 m) in diameter. "It was made of iron, with the upper part pierced for small circular plates of glass, for light, and in it were several water tight compartments." For propulsion, she was equipped with sixteen hand-powered paddles protruding from the sides, but on 3 July 1862, the Washington Navy Yard had the paddles replaced by a hand-cranked propeller, which improved its speed to about four knots.[1] Air was to be supplied from the surface by two tubes with floats, connected to an air pump inside the submarine.

The Navy wanted such a vessel to counter the threat posed to its wooden-hulled blockaders by the former screw frigate Merrimack which, according to intelligence reports, the Norfolk Navy Yard was rebuilding as an ironclad ram for the Confederacy (the CSS Virginia). The Navy's agreement with the Philadelphia shipbuilder specified that the submarine was to be finished in not more than 40 days; its keel was laid down almost immediately following the signing on 1 November 1861 of the contract for her construction. Nevertheless, the work proceeded so slowly that more than 180 days had elapsed when the novel craft finally was launched on 1 May 1862.

Operational history

Soon after being launched, she was towed to the Philadelphia Navy Yard to be fitted out and manned. A fortnight later, she was placed under command of a civilian, Mr. Samuel Eakins. On 13 June, the Navy formally accepted this small, unique ship.

Next, the steam tug Fred Kopp was engaged to tow the submarine to Hampton Roads, Virginia. The two vessels got underway on 19 June and proceeded down the Delaware River to the Delaware and Chesapeake Canal through which they entered the Chesapeake Bay for the last leg of the voyage. At Norfolk, the submarine was moored alongside the sidewheel steamer Satellite which was to act as her tender during her service with the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. A short while after reaching Hampton Roads on the 23rd, the submarine acquired the name Alligator, a moniker which soon appeared in official correspondence.

Several tasks were considered for the strange vessel: destroying a bridge across Swift Creek, a tributary of the Appomattox River; clearing away the obstructions in the James River at Fort Darling which had prevented Union gunboats from steaming upstream to support General McClellan's drive up the peninsula toward Richmond; and blowing up Virginia II if that ironclad were completed on time and sent downstream to attack Union forces. Consequently, the submarine was sent up the James to City Point where she arrived on the 25th. Commander John Rodgers, the senior naval officer in that area, examined Alligator and reported that neither the James off Fort Darling nor the Appomattox near the bridge was deep enough to permit the submarine to submerge completely. Moreover, he feared that while his theater of operation contained no targets accessible to the submarine, the Union gunboats under his command would be highly vulnerable to her attacks should Alligator fall into enemy hands. He therefore requested permission to send the submarine back to Hampton Roads.

The ship headed downriver on the 29th and then was ordered to proceed to the Washington Navy Yard for more experimentation and testing. In August, Lt. Thomas O. Selfridge, Jr. was given command of Alligator and she was assigned a naval crew. The tests proved unsatisfactory, and Selfridge pronounced "the enterprise… a failure."

The Navy Yard on 3 July 1862 replaced Alligator's oars with a hand cranked screw propeller, thereby increasing her speed to about 4 knots (7.4 km/h). On 18 March 1863, President Lincoln observed the submarine in operation.

About this time, Rear Admiral Samuel Francis du Pont—who had become interested in the submarine while in command of the Philadelphia Navy Yard early in the war—decided that Alligator might be useful in carrying out his plans to take Charleston, South Carolina, the birthplace of secession. Acting Master John F. Winchester, who then commanded the Sumpter, was ordered to tow the submarine to Port Royal, South Carolina. The odd pair got underway on 31 March.

The next day, the two ships encountered bad weather which, on 2 April, forced Sumpter to cut Alligator adrift off Cape Hatteras.[2] She either immediately sank or drifted for a while before sinking, ending the career of the United States Navy's first submarine.

See also

References

- ↑ "Alligator IV". Dictionary of American Naval Fightin Ships. Naval History and Heritage Command, United States Navy Department. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ Submarine Photo Index

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- Veit, Chuck, "The Innovative, Mysterious Alligator" - Naval History magazine (August 2010), pp. 26–29