American Idol

| American Idol | |

|---|---|

| |

| Also known as |

American Idol: The Search for a Superstar (season 1) American Idol XIII (season 13) American Idol XIV (season 14) |

| Genre | Reality television |

| Created by | Simon Fuller |

| Directed by |

|

| Presented by |

|

| Judges |

|

| Theme music composer |

|

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language(s) | English |

| No. of seasons | 14 |

| No. of episodes | 505 (as of January 8, 2015) (list of episodes) |

| Production | |

| Executive producer(s) |

|

| Running time | 22–104 minutes |

| Production company(s) | |

| Distributor | FremantleMedia Enterprises |

| Broadcast | |

| Original channel | Fox |

| Picture format | |

| Original run | June 11, 2002 – present |

| External links | |

| Website | |

American Idol is an American singing competition series created by Simon Fuller and produced by 19 Entertainment, and is distributed by FremantleMedia North America. It began airing on Fox on June 11, 2002, as an addition to the Idols format based on the British series Pop Idol and has since become one of the most successful shows in the history of American television. For an unprecedented eight consecutive years, from the 2003–04 television season through the 2010–11 season, either its performance or result show had been ranked number one in U.S. television ratings.[3]

The concept of the series is to find new solo recording artists, with the winner being determined by the viewers in America. Winners chosen by viewers through telephone, Internet, and SMS text voting were Kelly Clarkson, Ruben Studdard, Fantasia Barrino, Carrie Underwood, Taylor Hicks, Jordin Sparks, David Cook, Kris Allen, Lee DeWyze, Scotty McCreery, Phillip Phillips, Candice Glover and Caleb Johnson.

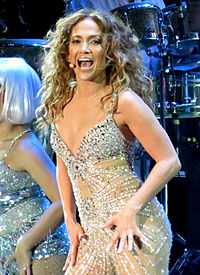

American Idol employs a panel of judges who critique the contestants' performances. The original judges were record producer and music manager Randy Jackson, pop singer and choreographer Paula Abdul and music executive and manager Simon Cowell. The judging panel for the most recent season consisted of country singer Keith Urban, singer and actress Jennifer Lopez, and jazz singer Harry Connick, Jr.[4] The show was originally hosted by radio personality Ryan Seacrest and comedian Brian Dunkleman, with Seacrest continuing on for the rest of the seasons.

The success of American Idol has been described as "unparalleled in broadcasting history".[5] The series was also said by a rival TV executive to be "the most impactful show in the history of television".[6] It has become a recognized springboard for launching the career of many artists as bona fide stars. According to Billboard magazine, in its first ten years, "Idol has spawned 345 Billboard chart-toppers and a platoon of pop idols, including Kelly Clarkson, Carrie Underwood, Daughtry, Fantasia, Ruben Studdard, Jennifer Hudson, Clay Aiken, Adam Lambert and Jordin Sparks while remaining a TV ratings juggernaut."[7]

History

American Idol was based on the British show Pop Idol created by Simon Fuller, which was in turn inspired by the New Zealand television singing competition Popstars. Television producer Nigel Lythgoe saw it in Australia and helped bring it over to Britain.[8] Fuller was inspired by the idea from Popstars of employing a panel of judges to select singers in audition. He then added other elements, such as telephone voting by the viewing public (which at the time was already in use in shows such as the Eurovision Song Contest), the drama of backstories and real-life soap opera unfolding in real time.[9] The show debuted in 2001 in Britain with Lythgoe as showrunner—the executive producer and production leader—and Simon Cowell as one of the judges, and was a big success with the viewing public.[10]

In 2001, Fuller, Cowell, and TV producer Simon Jones attempted to sell the Pop Idol format to the United States, but the idea was met with poor response from United States television networks.[11] However, Rupert Murdoch, head of Fox's parent company, was persuaded to buy the show by his daughter Elisabeth, who was a fan of the British show.[11] The show was renamed American Idol: The Search for a Superstar and debuted in the summer of 2002. Cowell was initially offered the job as showrunner but refused; Lythgoe then took over that position. Much to Cowell's surprise, it became one of the hit shows for the summer that year.[12][13] The show, with the personal engagement of the viewers with the contestants through voting, and the presence of the acid-tongued Cowell as a judge, grew into a phenomenon. By 2004, it had became the most-watched TV shows in the U.S., a position it then held on for eight straight years.[14]

Judges and hosts

Judges

The show had originally planned on having four judges following the Pop Idol format; however, only three judges had been found by the time of the audition round in the first season, namely Randy Jackson, Paula Abdul and Simon Cowell.[11] A fourth judge, radio DJ Stryker, was originally chosen but he dropped out citing "image concerns".[15] In the second season, New York radio personality Angie Martinez had been hired as a fourth judge but withdrew only after a few days of auditions due to not being comfortable with giving out criticism.[16] The show decided to continue with the three judges format until season eight. All three original judges stayed on the judging panel for eight seasons.

In season eight, Latin Grammy Award-nominated singer–songwriter and record producer Kara DioGuardi was added as a fourth judge. She stayed for two seasons and left the show before season ten.[17] Paula Abdul left the show before season nine after failing to agree terms with the show producers.[18] Emmy Award-winning talk show host Ellen DeGeneres replaced Paula Abdul for that season, but left after just one season.[19] On January 11, 2010, Simon Cowell announced that he was leaving the show to pursue introducing the American version of his show The X Factor to the USA for 2011.[20] Jennifer Lopez and Steven Tyler joined the judging panel in season ten,[21] but both left after two seasons.[22] They were replaced by three new judges, Mariah Carey, Nicki Minaj and Keith Urban, who joined Randy Jackson in season 12.[23] However both Carey and Minaj left after one season,[24] and Randy Jackson also announced that he would depart the show after twelve seasons as a judge but would return as a mentor.[25][26] Urban is the only judge from season 12 to return in season 13. He was joined by previous judge Jennifer Lopez and former mentor Harry Connick, Jr..[4] Lopez, Urban and Connick, Jr. all returned as judges for the show's fourteenth season.[27]

Guest judges may occasionally be introduced. In season two, guest judges such as Lionel Richie and Robin Gibb were used, and in season three Donna Summer, Quentin Tarantino and some of the mentors also joined as judges to critique the performances in the final rounds. Guest judges were used in the audition rounds for seasons four, six, nine, and fourteen such as Gene Simmons and LL Cool J in season four, Jewel and Olivia Newton-John in season six, Shania Twain in season eight, Neil Patrick Harris and Katy Perry in season nine, and season eight runner up, Adam Lambert, in season fourteen.

| Judges timeline |

|---|

|

Hosts

The first season was co-hosted by Ryan Seacrest and Brian Dunkleman. Dunkleman quit thereafter,[28] making Seacrest the sole emcee of the show starting with season two.

In-house mentors

Beginning in the tenth season, permanent mentors were brought in during the live shows to help guide the contestants with their song choice and performance. Jimmy Iovine was the mentor in the tenth through twelfth seasons, former judge Randy Jackson was the mentor for the thirteenth season and Scott Borchetta was the mentor for the fourteenth season. The mentors regularly bring in guest mentors to aid them, including Akon, Alicia Keys, Lady Gaga, and current judge Harry Connick, Jr..

Selection process

In a series of steps, the show selects the eventual winner out of many tens of thousands of contestants.

Contestant eligibility

The eligible age-range for contestants is currently fifteen to twenty-eight years old. The initial age limit was sixteen to twenty-four in the first three seasons, but the upper limit was raised to twenty-eight in season four, and the lower limit was reduced to fifteen in season ten. The contestants must be legal U.S. residents, cannot have advanced to particular stages of the competition in previous seasons (varies depending on the season, currently by the semi-final stage until season thirteen), and must not hold any current recording or talent representation contract by the semi-final stage[29] (in previous years by the audition stage).[30]

Initial auditions

Contestants go through at least three sets of cuts. The first is a brief audition with a few other contestants in front of selectors which may include one of the show's producers. Although auditions can exceed 10,000 in each city, only a few hundred of these make it past the preliminary round of auditions. Successful contestants then sing in front of producers, where more may be cut. Only then can they proceed to audition in front of the judges, which is the only audition stage shown on television.[31] Those selected by the judges are sent to Hollywood. Between 10–60 people in each city may make it to Hollywood.

Hollywood week and Las Vegas round

Once in Hollywood, the contestants perform individually or in groups in a series of rounds. Until season ten, there were usually three rounds of eliminations in Hollywood. In the first round the contestants emerged in groups but performed individually. For the next round, the contestants put themselves in small groups and perform a song together. In the final round, the contestants perform solo with a song of their choice a cappella or accompanied by a band—depending on the season. In seasons two and three, contestants were also asked to write original lyrics or melody in an additional round after the first round. In season seven, the group round was eliminated and contestants may, after a first solo performance and on judges approval, skip a second solo round and move directly to the final Hollywood round. In season twelve, the executive producers split up the females and males and chose the members to form the groups in the group round.

In seasons ten and eleven, a further round was added in Las Vegas, where the contestants perform in groups based on a theme, followed by one final solo round to determine the semi-finalists. At the end of this stage of the competition, 24 to 36 contestants are selected to move on to the semi-final stage. In season twelve the Las Vegas round became a Sudden Death round, where the judges had to choose five guys and five girls each night (4 nights) to make the top twenty. In season thirteen, a new round called "Hollywood or Home" was added, where if the judges were uncertain about some contestants, those contestants were required to perform soon after landing in Los Angeles, and those who failed to impress were sent back home before they reached Hollywood.

Audience voting

From the semi-finals onwards, the fate of the contestants is decided by public vote. During the contestant's performance as well as the recap at the end, a toll-free telephone number for each contestant is displayed on the screen. For a two-hour period after the episode ends (up to four hours for the finale) in each US time zone, viewers may call or send a text message to their preferred contestant's telephone number, and each call or text message is registered as a vote for that contestant. Viewers are allowed to vote as many times as they can within the two-hour voting window. However, the show reserves the right to discard votes by power dialers.[32] One or more of the least popular contestants may be eliminated in successive weeks until a winner emerges. Over 110 million votes were cast in the first season, and by season ten the seasonal total had increased to nearly 750 million. Voting via text messaging was made available in the second season when AT&T Wireless joined as a sponsor of the show, and 7.5 million text messages were sent to American Idol that season.[33] The number of text messages rapidly increased, reaching 178 million texts by season eight.[34] Online voting was offered for the first time in season ten. The votes are counted and verified by Telescope Inc.[35]

Semi-finals

In the first three seasons, the semi-finalists were split into different groups to perform individually in their respective night. In season one, there were three groups of ten, with the top three contestants from each group making the finals. In seasons two and three, there were four groups of eight, and the top two of each selected. These seasons also featured a wildcard round, where contestants who failed to qualify were given another chance. In season one, only one wildcard contestant was chosen by the judges, giving a total of ten finalists. In seasons two and three, each of the three judges championed one contestant with the public advancing a fourth into the finals, making 12 finalists in all.

From seasons four to seven and nine, the twenty-four semi-finalists were divided by gender in order to ensure an equal gender division in the top twelve. The men and women sang separately on consecutive nights, and the bottom two in each groups were eliminated each week until only six of each remained to form the top twelve.

The wildcard round returned in season eight, wherein there were three groups of twelve, with three contestants moving forward – the highest male, the highest female, and the next highest-placed singer - for each night, and four wildcards were chosen by the judges to produce a final 13. Starting season ten, the girls and boys perform on separate nights. In seasons ten and eleven, five of each gender were chosen, and three wildcards were chosen by the judges to form a final 13. In season twelve, the top twenty semifinalists were split into gender groups, with five of each gender advancing to form the final 10. In season thirteen, there were thirty semifinalists, but only twenty semifinalists (ten for each gender) were chosen by the judges to perform on the live shows, with five in each gender and three wildcards chosen by the judges composing the final 13.

Finals

The finals are broadcast in prime time from CBS Television City in Los Angeles, in front of a live studio audience. The finals lasted eight weeks in season one, eleven weeks in subsequent seasons until seasons ten and eleven which lasted twelve weeks except for season twelve, which lasted ten weeks, and season thirteen, which lasted for thirteen weeks. Each finalist performs songs based on a weekly theme which may be a musical genre such as Motown, disco, or big band, songs by artists such as Michael Jackson, Elvis Presley or The Beatles, or more general themes such as Billboard Number 1 hits or songs from the contestant's year of birth. Contestants usually work with a celebrity mentor related to the theme. In season ten, Jimmy Iovine was brought in as a mentor for the season. Initially the contestants sing one song each week, but this is increased to two songs from top four or five onwards, then three songs for the top two or three.

The most popular contestants are usually not revealed in the results show, instead typically the three contestants (two in later rounds) who received the lowest number of votes are called to the center of the stage. One of these three is usually sent to safety, the two remaining however are not necessarily the bottom two.[36] The contestant with the fewest votes is then revealed and eliminated from the competition. A montage of the eliminated contestant's time on the show is played and they give their final performance. However, in season six, during the series' first ever Idol Gives Back episode, no contestant was eliminated, but on the following week, two were sent home. Moreover, starting in season eight, the judges may overturn viewers' decision with a "Judges' Save" if they unanimously agree to. "The save" can only be used once, and only up through the top five. In the eighth, ninth, tenth, and fourteenth seasons, a double elimination then took place in the week following the activation of the save, but in the eleventh and thirteenth seasons, a regular single elimination took place. The save was not activated in the twelfth season and consequently, a non-elimination took place in the week after its expiration with the votes then carrying over into the following week.

The "Fan Save" was introduced in the fourteenth season. During the finals, viewers are given a five-minute window to vote for the contestants in danger of elimination by using their Twitter account to decide which contestant will move on to the next show, starting with the Top 8.

Season finale

In the finale, the two remaining contestants perform to determine the winner. For the first six seasons, apart from season two, the finale was broadcast from the Kodak Theatre, which has an audience capacity of approximately 3,400. The finale for season two took place at the Gibson Amphitheatre, which has an audience capacity of over 6,000. From season seven onwards, the venue was changed to the Nokia Theatre, which holds an audience of over 7,000. A two-hour results show the next night follows, where the winner is announced at the end.

Rewards for winner and finalists

The winner receives a record deal with a major label, which may be for up to six albums,[37][38] and secures a management contract with American Idol-affiliated 19 Management (which has the right of first refusal to sign all contestants), as well as various lucrative contracts. All winners prior to season nine reportedly earned at least $1 million in their first year as winner.[38] All the runners-up of the first ten seasons, as well as some of other finalists, have also received record deals with major labels. However, starting in season 11, the runner-up may only be guaranteed a single-only deal.[39] BMG/Sony (seasons 1–9) and UMG (season 10–) had the right of first refusal to sign contestants for three months after the season's finale. Starting in the fourteenth season, the winner was signed with Big Machine Records. Prominent music mogul Clive Davis also produced some of the selected contestants' albums, such as Kelly Clarkson, Clay Aiken, Fantasia Barrino and Diana DeGarmo. All top 10 (11 in seasons 10 and 12) finalists earn the privilege ofs going on a tour, where the participants may each earn a six-figure sum.[40]

Series overview and season synopses

Each season premieres with the audition round, taking place in different cities. The audition episodes typically feature a mix of potential finalists, interesting characters and woefully inadequate contestants. Each successful contestant receives a golden ticket to proceed on to the next round in Hollywood. Based on their performances during the Hollywood round (Las Vegas round for seasons 10 onwards), 24 to 36 contestants are selected by the judges to participate in the semifinals. From the semifinal onwards the contestants perform their songs live, with the judges making their critiques after each performance. The contestants are voted for by the viewing public, and the outcome of the public votes is then revealed in the results show typically on the following night. The results shows feature group performances by the contestants as well as guest performers. The Top-three results show also features the homecoming events for the Top 3 finalists. The season reaches its climax in a two-hour results finale show, where the winner of the season is revealed.

With the exception of seasons one and two, the contestants in the semifinals onwards perform in front of a studio audience. They perform with a full band in the finals. From season four to season nine, the American Idol band was led by Rickey Minor; from season ten onwards, Ray Chew. Assistance may also be given by vocal coaches and song arrangers, such as Michael Orland and Debra Byrd to contestants behind the scene. Starting with season seven, contestants may perform with a musical instrument from the Hollywood rounds onwards. In the first nine seasons, performances were usually aired live on Tuesday nights, followed by the results shows on Wednesdays in the United States and Canada, but moved to Wednesdays and Thursdays in season ten.

Season 1

The first season of American Idol debuted as a summer replacement show in June 2002 on the Fox network. It was co-hosted by Ryan Seacrest and Brian Dunkleman.

In the audition rounds, 121 contestants were selected from around 10,000 who attended the auditions. These were cut to 30 for the semifinal, with ten going on to the finals. One semifinalist, Delano Cagnolatti, was disqualified for lying to evade the show's age limit. One of the early favorites to win the show, Tamyra Gray, was eliminated at the top four, the first of several such shock eliminations that were to be repeated in later seasons. Christina Christian was hospitalized before the top six result show due to chest pains and palpitations, and she was eliminated while she was in the hospital.[41] Jim Verraros was the first openly gay contestant on the show; his sexual orientation was revealed in his online journal, however it was removed during the competition after a request from the show producers over concerns that it might be unfairly influencing votes.[42]

The final showdown was between Justin Guarini, one of the favorites, and Kelly Clarkson. Clarkson was not initially thought of as a contender,[43] but impressed the judges with some good performances in the final rounds, such as her performance of Aretha Franklin's "Natural Woman", and Betty Hutton's "Stuff Like That There", and eventually won the crown on September 4, 2002.

In what was to become a tradition, Clarkson performed the coronation song during the finale, and released the song immediately after the season ended. The single, "A Moment Like This", went on to break a 38-year-old record held by The Beatles for the biggest leap to number one on the Billboard Hot 100. Guarini did not release any song immediately after the show and remains the only runner-up not to do so. Both Clarkson and Guarini made a musical film, From Justin to Kelly, which was released in 2003 but was widely panned. Clarkson has since become the most successful Idol contestant around the world, with worldwide album sales of more than 23 million.[44]

Starting September 30, 2006, this season was repackaged as "American Idol Rewind" and syndicated directly to stations in the U.S.

Season 2

Following the success of season one, the second season was moved up to air in January 2003. The number of episodes increased, as did the show's budget and the charge for commercial spots. Dunkleman left the show, leaving Seacrest as the lone host. Kristin Adams was a correspondent for this season.[45]

Corey Clark was disqualified during the finals for having an undisclosed police record; however, he later alleged that he and Paula Abdul had an affair while on the show and that this contributed to his expulsion. Clark also claimed that Abdul gave him preferential treatment on the show due to their affair. The allegations were dismissed by Fox after an independent investigation.[46] Two semi-finalists were also disqualified that year – Jaered Andrews for an arrest on an assault charge, and Frenchie Davis for having previously modelled for an adult website.[47]

Ruben Studdard emerged as the winner, beating Clay Aiken by a small margin. Out of a total of 24 million votes, Studdard finished just 134,000 votes ahead of Aiken. This slim margin of victory was controversial due to the large number of calls that failed to get through.[48] In an interview prior to season five, executive producer Nigel Lythgoe indicated that Aiken had led the fan voting from the wildcard week onward until the finale.[49]

Both finalists found success after the show, but Aiken out-performed Studdard's coronation song "Flying Without Wings" with his single release from the show "This Is the Night", as well as in their subsequent album releases. The fourth-place finisher Josh Gracin also enjoyed some success as a country singer.[50]

Season 3

Season three premiered on January 19, 2004. One of the most talked-about contestants during the audition process was William Hung whose off-key rendition of Ricky Martin's "She Bangs" received widespread attention. His exposure on Idol landed him a record deal and surprisingly he became the third best-selling singer from that season.[51]

Much media attention on the season had been focused on the three black singers, Fantasia Barrino, LaToya London, and Jennifer Hudson, dubbed the Three Divas. All three unexpectedly landed on the bottom three on the top seven result show, with Hudson controversially eliminated.[52] Elton John, who was one of the mentors that season, called the results of the votes "incredibly racist".[53] The prolonged stays of John Stevens and Jasmine Trias in the finals, despite negative comments from the judges, had aroused resentment, so much so that John Stevens reportedly received a death threat, which he dismissed as a joke 'blown out of proportion'.[54]

The performance of "Summertime" by Barrino, later known simply as "Fantasia", at Top 8 was widely praised, and Simon Cowell considered it as his favorite Idol moment in the nine seasons he was on the show.[55] Fantasia and Diana DeGarmo were the last two finalists, and Fantasia was crowned as the winner. Fantasia released as her coronation single "I Believe", a song co-written by season one finalist Tamyra Gray, and DeGarmo released "Dreams". Fantasia went on to gain some successes as a recording artist, while Hudson, who placed seventh became the only Idol-contestant so far to win both an Academy Award and a Grammy.[50]

Season 4

Season four premiered on January 18, 2005; this was the first season of the series to be aired in high definition, although the finale of season three was also aired in high definition. The number of those attending the auditions by now had increased to over 100,000 from the 10,000 of the first season. The age limit was raised to 28 in this season,[30] among those who benefited from this new rule were Constantine Maroulis and Bo Bice, the two rockers of the show.

The top 12 finalists originally included Mario Vazquez, but he dropped out citing 'personal reasons'[56] and was replaced by Nikko Smith. Later, an employee of Freemantle Media which produces the show sued the company for wrongful termination, claiming that he was dismissed after complaining about lewd behavior by Vazquez toward him during the show.[57]

At top 11, due to a mix-up with the contestants' telephone number, voting was repeated on what was normally the result night, with the result reveal postponed until the following night.

In May 2005, Carrie Underwood was announced the winner, with Bice the runner-up. Both Underwood and Bice released the coronation song "Inside Your Heaven". Underwood has since sold 65 million records worldwide,[58] and become the most successful Idol contestant in the U.S. in terms of album sales, selling over 14 million albums copies in the U.S.[59] Underwood has won seven Grammy Awards, the most Grammys by an "American Idol" alumnus.[58][60]

Season 5

Season five began on January 17, 2006. It remains the highest-rated season in the show's run so far. Two of the more prominent contestants during the Hollywood round were the Brittenum twins who were later disqualified for identity theft.[61]

Chris Daughtry's performance of Fuel's "Hemorrhage (In My Hands)" on the show was widely praised and led to an invitation to join the band as Fuel's new lead singer, an invitation he declined.[62] His performance of Live's version of "I Walk the Line" was well received by the judges but later criticized in some quarters for not crediting the arrangement to Live.[63] He was eliminated at the top four in a shock result.

On May 30, 2006, Taylor Hicks was named American Idol, with Katharine McPhee the runner-up. "Do I Make You Proud" was released as Hicks' first single and McPhee's "My Destiny".

Despite being eliminated earlier in the season, Chris Daughtry (as lead of the band Daughtry) became the most successful recording artist from this season.[59] Other contestants, such as Hicks, McPhee, Bucky Covington, Mandisa, Kellie Pickler, and Elliott Yamin have had varying levels of success.

Season 6

Season six began on Tuesday, January 16, 2007. The premiere drew a massive audience of 37.3 million viewers, peaking in the last half hour with more than 41 million viewers.[64]

Teenager Sanjaya Malakar was the season's most talked-about contestant for his unusual hairdo,[65] and for managing to survive elimination for many weeks due in part to the weblog Vote for the Worst and satellite radio personality Howard Stern, who both encouraged fans to vote for him. However, on April 18, Sanjaya was voted off.[66]

This season saw the first Idol Gives Back telethon-inspired event, which raised more than $76 million in corporate and viewer donations.[67] No contestant was eliminated that week, but two (Phil Stacey and Chris Richardson) were eliminated the next. Melinda Doolittle was eliminated in the final three.

In the May 23 season finale, Jordin Sparks was declared the winner with the runner-up being Blake Lewis. Sparks has had some success as a recording artist post-Idol.

This season also saw the launch of the American Idol Songwriter contest which allows fans to vote for the "coronation song". Thousands of recordings of original songs were submitted by songwriters, and 20 entries selected for the public vote. The winning song, "This Is My Now", was performed by both finalists during the finale and released by Sparks on May 24, 2007.[68]

Season 7

Season seven premiered on January 15, 2008, for a two-day, four-hour premiere. The media focused on the professional status of the season seven contestants, the so-called 'ringers',[69] many of whom, including Kristy Lee Cook, Brooke White, Michael Johns, and in particular Carly Smithson, had prior recording contracts.[70] Contestant David Hernandez also attracted some attention due to his past employment as a stripper.[71]

For the finals, American Idol debuted a new state-of-the-art set and stage on March 11, 2008, along with a new on-air look. David Cook's performance of "Billie Jean" on top-ten night was lauded by the judges, but provoked controversy when they apparently mistook the Chris Cornell arrangement to be David Cook's own even though the performance was introduced as Cornell's version. Cornell himself said he was 'flattered' and praised David Cook's performance.[72] David Cook was taken to the hospital after the top-nine performance show due to heart palpitations and high blood pressure.[73]

David Archuleta's performance of John Lennon's "Imagine" was considered by many as one of the best of the season. Jennifer Lopez, who was brought in as a judge in season ten, called it a beautiful song-moment that she will never forget.[74] Jason Castro's semi-final performance of "Hallelujah" also received considerable attention, and it propelled Jeff Buckley's version of the song to the top of the Billboard digital song chart.[75] This was the first season in which contestants' recordings were released onto iTunes after their performances, and although sales information was not released so as not to prejudice the contest, leaked information indicated that contestants' songs frequently reached the top of iTunes sales chart.[76]

Idol Gives Back returned on April 9, 2008, and raised $64 million for charity.[67]

The finalists were Cook and Archuleta. David Cook was announced the winner on May 21, 2008, the first rocker to win the show. Both Cook and Archuleta had some success as recording artists with both selling over a million albums in the U.S.[59]

The American Idol Songwriter contest was also held this season. From ten of the most popular submissions, each of the final two contestants chose a song to perform, although neither of their selections was used as the "coronation song". The winning song, "The Time of My Life", was recorded by David Cook and released on May 22, 2008.

Season 8

Season eight premiered on January 13, 2009. Mike Darnell, the president of alternative programming for Fox, stated that the season would focus more on the contestants' reality and emotional state.[77] Much early attention on the show was therefore focused on the widowhood of Danny Gokey.

In the first major change to the judging panel, a fourth judge, Kara DioGuardi, was introduced. This was also the first season without executive producer Nigel Lythgoe who left to focus on the international versions of his show So You Think You Can Dance.[78] The Hollywood round was moved to the Kodak Theatre for 2009 and was also extended to two weeks. Idol Gives Back was canceled for this season due to the global recession at the time.

There were 13 finalists this season, but two were eliminated in its first result show of the finals. A new feature introduced was the "Judges' Save", and Matt Giraud was saved from elimination at the top seven by the judges when he received the fewest votes. The next week, Lil Rounds and Anoop Desai were eliminated.

The two finalists were Kris Allen and Adam Lambert, both of whom had previously landed in the bottom three at the top five. Allen won the contest in the most controversial voting result since season two. It was claimed,[79] later retracted,[80] that 38 million of the 100 million votes cast on the night came from Allen's home state of Arkansas alone, and that AT&T employees unfairly influenced the votes by giving lessons on power-texting at viewing parties in Arkansas.[81]

Both Allen and Lambert released the coronation song, "No Boundaries" which was co-written by DioGuardi. This is the first season in which the winner has failed to achieve gold album status, and none from that season achieved platinum album status in the U.S.

Season 9

Season nine premiered on January 12, 2010. The upheaval at the judging panel continued. Ellen DeGeneres joined as a judge to replace Paula Abdul at the start of Hollywood Week.

One of the most prominent auditioners this season was General Larry Platt whose performance of "Pants on the Ground" became a viral hit song.[82]

Crystal Bowersox, who has Type-I diabetes, fell ill due to diabetic ketoacidosis on the morning of the girls performance night for the top 20 week and was hospitalized.[83] The schedule was rearranged so the boys performed first and she could perform the following night instead; she later revealed that Ken Warwick, the show producer, wanted to disqualify her but she begged to be allowed to stay on the show.[83]

Michael Lynche was the lowest vote getter at top nine and was given the Judges' Save. The next week Katie Stevens and Andrew Garcia were eliminated. That week, Adam Lambert was invited back to be a mentor, the first Idol alum to do so. Idol Gives Back returned this season on April 21, 2010, and raised $45 million.[67]

A special tribute to Simon Cowell was presented in the finale for his final season with the show. Many figures from the show's past, including Paula Abdul, made an appearance.

The final two contestants were Lee DeWyze and Bowersox. DeWyze was declared the winner during the May 26 finale. No new song was used as coronation song this year; instead, the two finalists each released a cover song – DeWyze chose U2's "Beautiful Day", and Bowersox chose Patty Griffin's "Up to the Mountain". This is the first season where neither finalist achieved significant album sales.[84]

Season 10

Season ten of the series premiered on January 19, 2011. Many changes were introduced this season, from the format to the personnel of the show. Jennifer Lopez and Steven Tyler joined Randy Jackson as judges following the departures of Simon Cowell (who left to launch the U.S. version of The X Factor), Kara DioGuardi (whose contract was not renewed) and Ellen DeGeneres,[21] while Nigel Lythgoe returned as executive producer. Jimmy Iovine, chairman of the Interscope Geffen A&M label group, the new partner of American Idol, acted as the in-house mentor in place of weekly guest mentors,[21] although in later episodes special guest mentors such as Beyoncé, will.i.am and Lady Gaga were brought in.

Season ten is the first to include online auditions where contestants could submit a 40-second video audition via Myspace.[85] Karen Rodriguez was one such auditioner and reached the final rounds.

One of the more prominent contestants this year was Chris Medina, whose story of caring for his brain-damaged fiancée received widespread coverage.[86] Medina was cut in the Top 40 round. Casey Abrams, who suffers from ulcerative colitis, was hospitalized twice and missed the Top 13 result show. The judges used their one save on Abrams on the Top 11, and as a result this was the first season that 11 finalists went on tour instead of 10. In the following week, Naima Adedapo and Thia Megia were both eliminated the following week.

Pia Toscano, one of the presumed favorites to advance far in the season, was unexpectedly eliminated on April 7, 2011, finishing in ninth place. Her elimination drew criticisms from some former Idol contestants, as well as actor Tom Hanks.[87]

The two finalists in 2011 were Lauren Alaina and Scotty McCreery, both teenage country singers. McCreery won the competition on May 25, being the youngest male winner and the fourth male in a row to win American Idol. McCreery released his first single, "I Love You This Big", as his coronation song, and Alaina released "Like My Mother Does". McCreery's debut album, Clear as Day, became the first debut album by an Idol winner to reach No. 1 on the US Billboard 200 since Ruben Studdard's Soulful in 2003, and he became the youngest male artist to reach No. 1 on the Billboard 200.[88]

Season 11

Season 11 premiered on January 18, 2012. On February 23, it was announced that one more finalist would join the Top 24 making it the Top 25, and that was Jermaine Jones. However, on March 14, Jones was disqualified in 12th place for concealing arrests and outstanding warrants. Jones denied the accusation that he concealed his arrests.[89]

Finalist Phillip Phillips suffered from kidney pain and was taken to hospital before the Top 13 results show, and later received medical procedure to alleviate a blockage caused by kidney stones.[90] He was reported to have eight surgeries during his Idol run, and had considered quitting the show due to the pain.[91] He underwent surgery to remove the stones and reconstruct his kidney soon after the season had finished.[92]

Jessica Sanchez received the fewest number of votes during the Top 7 week, and the judges decided to use their "save" option on her, making her the first female recipient of the save. The following week, unlike previous seasons, Colton Dixon was the only contestant sent home. Sanchez later made the final two, the first season where a recipient of the save reached the finale.

Phillips became the winner, beating Sanchez. Prior to the announcement of the winner, season five finalist Ace Young proposed marriage to season three runner-up Diana DeGarmo on stage – which she accepted.

Phillips released "Home" as his coronation song, while Sanchez released "Change Nothing". Phillips' "Home" has since become the best selling of all coronation songs.[93]

Season 12

Season 12 premiered on January 16, 2013. Judges Jennifer Lopez and Steven Tyler left the show after two seasons. This season's judging panel consisted of Randy Jackson, along with Mariah Carey, Keith Urban and Nicki Minaj. This was the first season since season nine to have four judges on the panel. The pre-season buzz and the early episodes of the show were dominated by the feud between the judges Minaj and Carey after a video of their dispute was leaked to TMZ.[94]

The top 10 contestants started with five males and five females, however, the males were eliminated consecutively in the first five weeks, with Lazaro Arbos the last male to be eliminated. For the first time in the show's history, the top 5 contestants were all female. It was also the first time that the judges' "save" was not used, the top four contestants were therefore given an extra week to perform again with their votes carried over with no elimination in the first week.

23-year-old Candice Glover won the season with Kree Harrison taking the runner-up spot. Glover is the first female to win American Idol since Jordin Sparks. Glover released "I Am Beautiful" as a single while Harrison released "All Cried Out" immediately after the show. Glover sold poorly with her debut album, and this is also the first season that the runner-up was not signed by a music label.[95]

Towards the end of the season, Randy Jackson, the last remaining of the original judges, announced that he would no longer serve as a judge to pursue other business ventures.[25] Both judges Mariah Carey and Nicki Minaj also decided to leave after one season to focus on their music careers.[24]

Season 13

The thirteenth season premiered on January 15, 2014, with Ryan Seacrest returning as host. Randy Jackson and Keith Urban returned, though Jackson moved from the judging panel to the role of in-mentor. Mariah Carey and Nicki Minaj left the panel after one season. Former judge Jennifer Lopez and former mentor Harry Connick, Jr. joined Urban on the panel. Also, Nigel Lythgoe and Ken Warwick were replaced as executive producers by Per Blankens, Jesse Ignjatovic and Evan Pragger. Bill DeRonde replaced Warwick as a director of the audition episodes, while Louis J. Horvitz replaced Gregg Gelfand as a director of the show.[96]

This was the first season where the contestants were permitted to perform in the final rounds songs they wrote themselves. In the Top 8, Sam Woolf received the fewest votes, but he was saved from elimination by the judges. The 500th episode of the series was the Top 3 performance night.[97]

Caleb Johnson was named the winner of the season, with Jena Irene as the runner-up.[98] Johnson released "As Long as You Love Me" as his coronation single while Irene released "We Are One". Caleb Johnson's album however performed very poorly commercially.[99]

Season 14

The fourteenth season premiered on January 7, 2015. Ryan Seacrest returned to host, while Jennifer Lopez, Keith Urban and Harry Connick, Jr. returned for their respective fourth, third and second seasons as judges. Eighth season runner-up Adam Lambert filled in for Urban during the New York City auditions. Randy Jackson did not return as the in-house mentor for this season.[100] Changes this season include only airing one episode a week during the final ten.[101] Also Coca Cola ended their longtime sponsorship of the show.[102]

Geographical, ethnic, and gender bias

Since the show's inception in 2002, ten of the thirteen Idol winners, including its first five, have come from the Southern United States.[103] The three exceptions are: Jordin Sparks, from Arizona; David Cook, from Missouri (which is considered part of the "Upland South",[104] and he was born in Houston and living in Tulsa at the time of his audition); and Lee DeWyze, from Illinois. A large number of other notable finalists during the series' run have also hailed from the American South, including Clay Aiken, Kellie Pickler, and Chris Daughtry,[103] who are all from North Carolina. In 2012, an analysis of the 131 contestants who have appeared in the finals of all seasons of the show up to that point found that 48% have some connection to the Southern United States.[105]

The show itself is popular in the Southern United States, with households in the Southeastern United States 10% more likely to watch American Idol during the eighth season in 2009, and those in the East Central region, such as Kentucky, were 16 percent more likely to tune into the series.[103] Data from Nielsen SoundScan, a music-sales tracking service, showed that of the 47 million CDs sold by Idol contestants through January 2010, 85 percent were by contestants with ties to the American South.[103]

Theories given for the success of Southerners on Idol have been: more versatility with musical genres, as the Southern U.S. is home to several music genre scenes; not having as many opportunities to break into the pop music business; text-voting due to the South having the highest percentage of cell-phone only households; and the strong heritage of music and singing, which is notable in the Bible Belt, where it is in church that many people get their start in public singing.[103][106][107] Others also suggest that the Southern character of these contestants appeal to the South, as well as local pride.[108] According to season five winner Taylor Hicks, who is from the state of Alabama, "People in the South have a lot of pride ... So, they're adamant about supporting the contestants who do well from their state or region."[103]

For five consecutive seasons, starting in season seven, the title was given to a white male who plays the guitar – a trend that Idol pundits call the "White guy with guitar" or "WGWG" factor.[109] Just hours before the season eleven finale, where Phillip Phillips was named the winner, Richard Rushfield, author of the book American Idol: The Untold Story, said, "You have this alliance between young girls and grandmas and they see it, not necessarily as a contest to create a pop star competing on the contemporary radio, but as .... who's the nicest guy in a popularity contest," he says, "And that has led to this dynasty of four, and possibly now five, consecutive, affable, very nice, good-looking white boys."[109]

Controversy

The show had been criticized in earlier seasons over the onerous contract contestants had to sign that gave excessive control to 19 Entertainment over their future career,[110] and handed a large part of their future earnings to the management.[111][112]

Individual contestants have generated controversy in this competition for their past actions,[47][113] or for being 'ringers' planted by the producers.[69] A number of contestants had been disqualified for various reasons, such as for having an existing contract or undisclosed criminal records, although the show had been accused of double standard for disqualifying some but not the others.[114]

Voting results have been a consistent source of controversy. The mechanism of voting had also aroused considerable criticisms, most notably in season two when Ruben Studdard beat Clay Aiken in a close vote,[48] and in season eight, when the massive increase in text votes (100 million more text votes than season 7)[34] fueled the texting controversy.[81] Concerns about power voting have been expressed from the very first season.[115] Since 2004, votes also have been affected to a limited degree by online communities such as DialIdol, Vote for the Worst (closed in 2013), and Vote for the Girls (started 2010).

Idol Gives Back

Idol Gives Back is a special charity event started in season six featuring performances by celebrities and various fund-raising initiatives. This event was also held in seasons seven and nine and has raised nearly $185 million in total.[67]

U.S. television ratings

Seasonal rankings (based on average total viewers per episode) of American Idol. It holds the distinction of having the longest winning streak in the Nielsen annual television ratings; it became the highest-rated of all television programs in the United States overall for an unprecedented seven consecutive years,[116] or eight consecutive (and total) years when either its performance or result show was ranked number one overall .[3]

- Each U.S. network television season starts in late September and ends in late May, which coincides with the completion of May sweeps.

| Season | Premiered | Ended | TV season | Season Timeslot | Season viewers |

Season ranking | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Viewers (in millions) |

Date | Viewers (in millions) | |||||

| 1[117][118][119] | June 11, 2002 | 9.85 | Final Performances: September 3, 2002 | 18.69 | 2002 | Tuesday 9:00 pm (performance) |

12.07 | 30 |

| Season Finale: September 4, 2002 | 23.02 | Wednesday 9:30 pm (results) |

11.75 | 25 | ||||

| 2[117][118][120] | January 21, 2003 | 26.50 | Final Performances: May 20, 2003 | 25.67 | 2002–03 | Tuesday 8:00 pm (performance) |

21.03[121] | 5 |

| Season Finale: May 21, 2003 | 38.06 | Wednesday 8:30 pm (results) |

19.63[121] | 3 | ||||

| 3[117][118][122] | January 19, 2004 | 28.96 | Final Performances: May 25, 2004 | 25.13 | 2003–04 | Tuesday 8:00 pm (performance) |

25.73[123] | 1 |

| Season Finale: May 26, 2004 | 28.84 | Wednesday 8:30 pm (results) |

24.31[123] | 3 | ||||

| 4[117][118][124] | January 18, 2005 | 33.58 | Final Performances: May 24, 2005 | 28.05 | 2004–05 | Tuesday 8:00 pm (performance) |

27.32[125] | 1 |

| Season Finale: May 25, 2005 | 30.27 | Wednesday 8:00 pm (results) |

26.07[125] | 3 | ||||

| 5[117][118][126] | January 17, 2006 | 35.53 | Final Performances: May 23, 2006 | 31.78 | 2005–06 | Tuesday 8:00 pm (performance) |

31.17[127] | 1 |

| Season Finale: May 24, 2006 | 36.38 | Wednesday 8:00 pm (results) |

30.16[127] | 2 | ||||

| 6[117][118][128] | January 16, 2007 | 37.44 | Final Performances: May 22, 2007 | 25.33 | 2006–07 | Tuesday 8:00 pm (performance) |

30.11[129] | 2 |

| Season Finale: May 23, 2007 | 30.76 | Wednesday 8:00 pm (results) |

30.58[129] | 1 | ||||

| 7[117][130][131] | January 15, 2008 | 33.48 | Final Performances: May 20, 2008 | 27.06 | 2007–08 | Tuesday 8:00 pm (performance) |

28.80[132] | 1 |

| Season Finale: May 21, 2008 | 31.66 | Wednesday 8:00 pm (results) |

27.81[132] | 2 | ||||

| 8[117][133][134] | January 13, 2009 | 30.45 | Final Performances: May 19, 2009 | 23.82 | 2008–09 | Tuesday 8:00 pm (performance) |

26.25[135] | 2 |

| Season Finale: May 20, 2009 | 28.84 | Wednesday 8:00 pm (results) |

26.77[135] | 1 | ||||

| 9[117][136][137] | January 12, 2010 | 29.95 | Final Performances: May 25, 2010 | 20.07 | 2009–10 | Tuesday 8:00 pm (performance) |

22.97[138] | 1 |

| Season Finale: May 26, 2010 | 24.22 | Wednesday 8:00 pm (results) |

21.95[138] | 2 | ||||

| 10[139][140][141] | January 19, 2011 | 26.23 | Final Performances: May 24, 2011 (Tues) | 20.57 | 2010–11 | Wednesday 8:00 pm (performance) |

25.97[142] | 1 |

| Season Finale: May 25, 2011 (Wed) | 29.29 | Thursday 8:00 pm (results) |

23.87[142] | 2 | ||||

| 11[143][144][145] | January 18, 2012 | 21.93 | Final Performances: May 22, 2012 (Tues) | 14.85 | 2011–12 | Wednesday 8:00 pm (performance) |

19.81[146] | 2 |

| Season Finale: May 23, 2012 (Wed) | 21.49 | Thursday 8:00 pm (results) |

18.33[146] | 4 | ||||

| 12[147][148][149] | January 16, 2013 | 17.93 | Final Performances: May 15, 2013 (Tues) | 12.11 | 2012–13 | Wednesday 8:00 pm (performance) |

15.04[150] | 7 |

| Season Finale: May 16, 2013 (Wed) | 14.31 | Thursday 8:00 pm (results) |

14.65[150] | 9 | ||||

| 13[151][152][153] | January 15, 2014 | 15.19 | Final Performances: May 20, 2014 (Tues) | 6.76 | 2013–14 | Wednesday 8:00 pm (performance) |

11.94[154] | 17 |

| Season Finale: May 21, 2014 (Wed) | 10.53 | Thursday 8:00 pm (results) |

11.43[154] | 22 | ||||

| 14[155] | January 7, 2015 | 11.20 | Final Performances: May 12, 2015 (Tues) | TBC | 2014–15 | Wednesday 8:00 pm (results & performance March 19 onwards) |

||

| Season Finale: May 13, 2015 (Wed) | TBC | Thursday 8:00 pm (results until March 12) |

||||||

American Idol premiered in June 2002 and became the surprise summer hit show of 2002. The first show drew 9.9 million viewers, giving Fox the best viewing figure for the 8.30 pm spot in over a year.[156] The audience steadily grew, and by finale night, the audience had averaged 23 million, with more than 40 million watching some part of that show.[157] That episode was placed third amongst all age groups, but more importantly it led in the 18–49 demographic, the age group most valued by advertisers.[13]

The growth continued into the next season, starting with a season premiere of 26.5 million.[117] The season attracted an average of 21.7 million viewers, and was placed second overall amongst the 18–49 age group.[158] The finale night when Ruben Studdard won over Clay Aiken was also the highest-rated ever American Idol episode at 38.1 million for the final hour.[159] By season three, the show had become the top show in the 18–49 demographic[159] a position it has held for all subsequent years up to and including season ten, and its competition stages ranked first in the nationwide overall ratings. By season four, American Idol had become the most watched series amongst all viewers on American TV for the first time, with an average viewership of 26.8 million.[160] The show reached its peak in season five with numbers averaging 30.6 million per episode, and season five remains the highest-rated season of the series.[160]

Season six premiered with the series' highest-rated debut episode and a few of its succeeding episodes rank among the most watched episodes of American Idol. During this time, many television executives begun to regard the show as a programming force unlike any seen before,[6] as its consistent dominance of up to two hours two or three nights a week exceeded the 30- or 60-minute reach of previous hits such as NBC's The Cosby Show. The show was dubbed "the Death Star",[64] and competing networks often rearranged their schedules in order to minimize losses.[6] However, season six also showed a steady decline in viewership over the course of the season. The season finale saw a drop in ratings of 16% from the previous year. Season six was the first season wherein the average results show rated higher than the competition stages (unlike in the previous seasons), and became the second highest-rated of the series after the preceding season.[159]

The loss of viewers continued into season seven. The premiere was down 11% among total viewers,[117] and the results show in which Kristy Lee Cook was eliminated delivered its lowest-rated Wednesday show among the 18–34 demo since the first season in 2002.[161] However, the ratings rebounded for the season seven finale with the excitement over the battle of the Davids, and improved over season six as the series' third most watched finale. The strong finish of season seven also helped Fox become the most watched TV network in the country for the first time since its inception, a first ever in American television history for a non-Big Three major broadcast network.[162] Overall ratings for the season were down 10% from season six,[163] which is in line with the fall in viewership across all networks due in part to the 2007–2008 Writers Guild of America strike.[164]

The declining trend however continued into season eight, as total viewers numbers fell by 5–10% for early episodes compared to season seven,[165] and by 9% for the finale.[118] In season nine, Idol 's six-year extended streak of perfection in the ratings was broken, when NBC's coverage of the 2010 Winter Olympics on February 17 beat Idol in the same time slot with 30.1 million viewers over Idol's 18.4 million.[166] Nevertheless, American Idol overall finished its ninth season as the most watched TV series for the sixth year running, breaking the previous record of five consecutive seasons achieved by CBS' All in the Family and NBC's The Cosby Show.[167]

In season ten, the total viewer numbers for the first week of shows fell 12–13%, and by up to 23% in the 18–49 demo compared to season nine.[139] Later episodes, however, retained viewers better, and the season ended on a high with a significant increase in viewership for the finale – up 12% for the adults 18–49 demo and a 21% increase in total viewers from the season nine finale.[168] While the overall viewer number has increased this season, its viewer demographics have continued to age year on year – the median age this season was 47.2 compared to a median age of 32.1 in its first season.[169] By the time of the 2010-2011 television season, Fox was in its seventh consecutive season of victory overall in the 18-49 demographic ratings in the United States.

Season eleven, however, suffered a steep drop in ratings, a drop attributed by some to the arrival of new shows such as The Voice and The X-Factor.[170] The ratings for the first two episodes of season eleven fell 16–21% in overall viewer numbers and 24–27% in the 18/49 demo,[143] while the season finale fell 27% in total viewer number and 30% in the 18-49 demo.[144] The average viewership for the season fell below 20 million viewers the first time since 2003, a drop of 23% in total viewers and 30% in the 18/49 demo. For the first time in eight years, American Idol lost the leading position in both the total viewers number and the 18/49 demo, coming in second to NBC Sunday Night Football, although the strengths of Idol in its second year in the Wednesday-Thursday primetime slots helped Fox achieve the longest period of 18-49 demographic victory in the Nielsen ratings, standing at 8 straight years from 2004 to 2012.[145]

The loss of viewers continued into season 12, which saw the show hitting a number of series low in the 18-49 demo.[171] The finale had 7.2 million fewer viewers than the previous season, and saw a drop of 44% in the 18-49 demo.[172] The season viewers averaged at 13.3 million, a drop of 24% from the previous season.[173] The thirteenth season suffered a huge decline in the 18-49 demographic, a drop of 28% from the twelfth season, and American Idol lost its Top 10 position in the Nielsen ratings by the end of the 2013-2014 television season for the first time since its entry to the rankings in 2003 as a result, although the entire series to date had not yet been dropped from the Nielsen Top 30 rankings since its inception in 2002.[27]

Cultural impact

Television

The enormous success of the show and the revenue it generated was transformative for Fox Broadcasting Company. American Idol and fellow competing shows Survivor and Who Wants to Be a Millionaire were altogether credited for expanding reality television programming in the United States in the 1990s and 2000s, and Idol became the most watched non-scripted primetime television series for almost a decade, from 2003 to 2012, breaking records on U.S. television (dominated by drama shows and sitcoms in the preceding decades).[174]

The show pushed Fox to become the number one U.S. TV network amongst adults 18–49,[175] the key demographic coveted by advertisers, for an unprecedented eight consecutive years by 2012.[176] Its success also helped lift the ratings of other shows that were scheduled around it such as House and Bones, and Idol, for years, had become Fox's strongest platform primetime television program for promoting eventual hit shows of 2010s (of the same network) such as Glee and New Girl.[6] The show, its creator Simon Fuller claimed, "saved Fox".[177]

The show's massive success in the mid-2000s and early 2010s spawned a number of imitating singing-competition shows, such as Rock Star, Nashville Star, The Voice, Rising Star and The X Factor.[178][179] Its format also served as a blueprint for non-singing TV shows such as Dancing with the Stars and So You Think You Can Dance, of which almost all shows, however, would contribute to the currently highly competitive reality TV landscape on American television.[180]

Music

As one of the most successful shows on U.S. television history, American Idol has a strong impact not just on television, but also in the wider world of entertainment.[181] It helped create a number of highly successful recording artists, such as Kelly Clarkson, Daughtry and Carrie Underwood, as well as others of varying notability.

Various American Idol alumni had success on various record charts around the world; in the U.S. they had achieved 345 number ones on the Billboard charts in its first ten years.[7] According to Fred Bronson, author of books on the Billboard charts, no other entity has ever created as many hit-making artists and best-selling albums and singles.[182] In 2007, American Idol alums accounted for 2.1% of all music sales.[183] Its alumni have a massive impact on radio; in 2007, American Idol had become "a dominant force in radio" according to the president of the research company Mediabase which monitors radio stations Rich Meyer.[184] By 2010, four winners each had more than a million radio spins, with Kelly Clarkson leading the field with over four million spins.[185]

As of 2013, the American Idol alumni in their post-Idol careers have amassed over 59 million albums and 120 million singles and digital track downloads in the United States alone.

Film and theater

The impact of American Idol is also strongly felt in musical theatre, where many of Idol alumni have forged successful careers. The striking effect of former American Idol contestants on Broadway has been noted and commented on.[186][187] The casting of a popular Idol contestant can lead to significantly increased ticket sales. Other alumni have gone on to work in television and films, the most notable being Jennifer Hudson who, on the recommendation of the Idol vocal coach Debra Byrd,[188] won a role in Dreamgirls and subsequently received an Academy Award for her performance.

American Idol alumni accolades

| Idol contestant & season | American Music Awards | Billboard Music Awards | Grammy Awards | Academy Awards |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kelly Clarkson (Season 1, winner) |

4 2005 Favorite Adult Contemporary Artist 2005 Artist of the Year 2006 Favorite Pop/Rock Female 2006 Favorite Adult Contemporary Artist |

12 | 3 2006 Best Female Pop Vocal 2006 Best Pop Vocal Album 2013 Best Pop Vocal Album |

0 |

| Clay Aiken (Season 2, runner-up) |

1 2003 Fan's Choice Award |

3 | 0 | 0 |

| Fantasia Barrino (Season 3, winner) |

0 | 3 | 1 2011 Best Female R&B Vocal |

0 |

| Jennifer Hudson (Season 3, 7th place) |

0 | 0 | 1 2009 Best R&B Album |

1 2007 Best Supporting Actress |

| Carrie Underwood (Season 4, winner) |

8 2006 Breakthrough Artist 2007 Artist of the Year 2007 Favorite Country Album 2007 Country Female Artist 2008 Favorite Country Album 2010 Favorite Country Album 2012 Favorite Country Album 2014 Favorite Country Female Artist |

17 | 7 2007 Best New Artist 2007 Best Female Country Vocal 2008 Best Female Country Vocal 2009 Best Female Country Vocal 2010 Best Country Collaboration with Vocals 2013 Best Country Solo Performance 2015 Best Country Solo Performance |

0 |

| Chris Daughtry (Season 5, 4th place) |

4 2007 Breakthrough Artist 2007 Best Adult Contemporary Artist 2007 Best Pop/Rock Album 2008 Favorite Band, Duo or Group- Pop/Rock |

6 | 0 | 0 |

| Mandisa (Season 5, 9th Place) |

0 | 0 | 1 2014 Best Contemporary Christian Music Album |

0 |

| Jordin Sparks (Season 6, winner) |

1 2008 Favorite Adult Contemporary Artist |

0 | 0 | 0 |

Critical reception

Early reviews were mixed in their assessment. Ken Tucker of Entertainment Weekly considered that "As TV, American Idol is crazily entertaining; as music, it's dust-mote inconsequential".[189] Others, however, thought that "the most striking aspect of the series was the genuine talent it revealed".[13] It was also described as a "sadistic musical bake-off",[190] and "a romp in humiliation".[191] Other aspects of the show have attracted criticisms. The product placement in the show in particular was noted,[192] and some critics were harsh about what they perceived as its blatant commercial calculations – Karla Peterson of The San Diego Union-Tribune charged that American Idol is "a conniving multimedia monster" that has "absorbed the sin of our debauched culture and spit them out in a lump of reconstituted evil".[193] The decision to send the season one winner to sing the national anthem at the Lincoln Memorial on the first anniversary of the September 11 attacks in 2002 was also poorly received by many. Lisa de Moraes of The Washington Post noted with satirical flair that "The terrorists have won" and, with a sideswipe at the show's commercialism and voting process, that the decision as to who "gets to turn this important site into just another cog in the 'Great American Idol Marketing Mandala' is in the hands of the millions of girls who have made American Idol a hit. Them and a handful of phone-redialer geeks who have been clocking up to 10,000 calls each week for their contestant of choice (but who, according to Fox, are in absolutely no way skewing the outcome)."[194]

Some of the later writers about the show were more positive, Michael Slezak, again of Entertainment Weekly, thought that "for all its bloated, synthetic, product-shilling, money-making trappings, Idol provides a once-a-year chance for the average American to combat the evils of today's music business."[195] Singer Sheryl Crow, who was later to act as a mentor on the show, however took the view that the show "undermines art in every way and promotes commercialism".[196] Pop music critic Ann Powers nevertheless suggested that Idol has "reshaped the American songbook", "led us toward a new way of viewing ourselves in relationship to mainstream popular culture", and connects "the classic Hollywood dream to the multicentered popular culture of the future."[197] Others focused on the personalities in the show; Ramin Setoodeh of Newsweek accused judge Simon Cowell's cruel critiques in the show of helping to establish in the wider world a culture of meanness, that "Simon Cowell has dragged the rest of us in the mud with him."[198] Some such as singer John Mayer disparaged the contestants, suggesting that those who appeared on Idol are not real artists with self-respect.[199]

Some in the entertainment industry were critical of the star-making aspect of the show. Usher, a mentor on the show, bemoaning the loss of the "true art form of music", thought that shows like American Idol made it seem "so easy that everyone can do it, and that it can happen overnight", and that "television is a lie".[200] Musician Michael Feinstein, while acknowledging that the show had uncovered promising performers, said that American Idol "isn't really about music. It's about all the bad aspects of the music business – the arrogance of commerce, this sense of 'I know what will make this person a star; artists themselves don't know.' "[201] That American Idol is seen to be a fast track to success for its contestants has been a cause of resentment for some in the industry. LeAnn Rimes, commenting on Carrie Underwood winning Best Female Artist in Country Music Awards over Faith Hill in 2006, said that "Carrie has not paid her dues long enough to fully deserve that award".[202] It is a common theme that has been echoed by many others. Elton John, who had appeared as a mentor in the show but turned down an offer to be a judge on American Idol, commenting on talent shows in general, said that "there have been some good acts but the only way to sustain a career is to pay your dues in small clubs".[203]

The success of the show's alumni however has led to a more positive assessment of the show, and the show was described as having "proven it has a valid way to pick talent and a proven way to sell records".[204] While the industry is divided on the show success, according to a CMT exec, reflecting on the success of Idol alumni in the country genre, "if you want to try and get famous fast by going to a cattle call audition on TV, Idol reasonably remains the first choice for anyone," and that country music and Idol "go together well".[205]

American Idol was nominated for the Emmy's Outstanding Reality Competition Program for nine years but never won.[206] Director Bruce Gower won a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Directing For A Variety, Music Or Comedy Series in 2009, and the show won a Creative Arts Emmys each in 2007 and 2008, three in 2009, and two in 2011, as well as a Governor's Award in 2007 for its Idol Gives Back edition. It won the People's Choice Award, which honors the popular culture of the previous year as voted by the public, for favorite competition/reality show in 2005, 2006, 2007, 2010, 2011 and 2012.[207] It won the first Critics' Choice Television Award in 2011 for Best Reality Competition.[208]

Revenue and commercial ventures

The dominance of American Idol in the ratings has made it the most profitable show in U.S. TV for many years. The show was estimated to generate $900 million for the year 2004 through sales of TV ads, albums, merchandise and concert tickets.[177] By season seven, the show was estimated to earn around $900 million from its ad revenue alone, not including ancillary sponsorship deals and other income.[209][210] One estimate puts the total TV revenue for the first eight seasons of American at $6.4 billion.[211] Sponsors that bought fully integrated packages can expect a variety of promotions of their products on the show, such as product placement, adverts and product promotion integrated into the show, and various promotional opportunities.[212] Other off-air promotional partners pay for the rights to feature "Idol" branding on their packaging, products and marketing programs.[213] American Idol also partnered with Disney in its theme park attraction The American Idol Experience.

Advertising revenue

American Idol became the most expensive series on broadcast networks for advertisers starting season four,[214] and by the next season, it had broken the record in advertising rate for a regularly scheduled prime-time network series, selling over $700,000 for a 30-seconds slot,[215] and reaching up to $1.3 million for the finale.[216] Its ad prices reached a peak in season seven at $737,000.[210] Estimated revenue more than doubled from $404 million in season three to $870 million in season six.[217] While that declined from season eight onwards, it still earned significantly more than its nearest competitor,[218][219] with advertising revenue topping $800 million annually the next few seasons.[220] However, the sharp drop in ratings in season eleven also resulted in a sharp drop in advertising rate for season twelve, and the show lost its leading position as the costliest show for advertisers.[221]

Media sponsorship

Ford Motor Company and Coca-Cola were two of the first sponsors of American Idol in its first season. The sponsorship deal cost around $10 million in season one,[222] rising to $35 million by season 7,[213] and between $50 to $60 million in season 10.[223] The third major sponsor AT&T Wireless joined in the second season but ended after season 12, and Coca-Cola officially ended its sponsorship after season 13 amidst the declining ratings of Idol in the mid-2010s. iTunes sponsored the show since season seven.

American Idol prominent display of its sponsors' logo and products had been noted since the early seasons.[13][157] By season six, Idol showed 4,349 product placements according to Nielsen Media Research.[224] The branded entertainment integration proved beneficial to its advertisers – promotion of AT&T text-messaging as a means to vote successfully introduced the technology into the wider culture,[33][225] and Coca-Cola has seen its equity increased during the show.[226]

- Coca-Cola – Cups bearing logo of Coca-Cola, and occasionally its subsidiary Vitaminwater,[227] are featured prominently on the judges table. Contestants are shown between songs held in the "Coca-Cola Red Room", the show's equivalent of the green room. (The Coca-Cola logo however is obscured during rebroadcast in the UK which until 2011 banned product placement.[228])

- Ford – Contestants appear in the special Ford videos on the results shows, and winners Kelly Clarkson, Taylor Hicks, and Kris Allen have also appeared in commercials for Ford.[212] The final two each won a free Ford Mustang in seasons four, five and six, Ford Escape Hybrid in season seven, Ford Fusion Hybrid in season eight, Ford Fiesta in season nine, and 2013 Ford Fusion in season eleven. In season ten Scotty McCreery chose a Ford F-150 and Lauren Alaina chose Shelby Mustang. In the red room, there is a glass table with a Ford wheel as its base.

- AT&T – AT&T Mobility is promoted as the service provider for text-voting. AT&T created an ad campaign that centered on an air-headed teenager going around telling people to vote.

- Apple iTunes – Ryan Seacrest announces the availability of contestants' performances exclusively via iTunes. Videos are regularly shown of contestants learning their songs by rehearsing with iPods.

- Previous sponsors include Old Navy and Clairol's Herbal Essences. In seasons two and three, contestants sometimes donned Old Navy clothing for their performances with celebrity stylist Steven Cojocaru assisting with their wardrobe selection,[229] and contestants received Clairol-guided hair makeovers. In the season seven finale, both David Cook and David Archuleta appeared in "Risky Business"-inspired commercials for Guitar Hero, a sponsor of the tour that year.

Coca-Cola's archrival PepsiCo declined to sponsor American Idol at the show's start. What the Los Angeles Times later called "missing one of the biggest marketing opportunities in a generation" contributed to Pepsi losing market share, by 2010 falling to third place from second in the United States. PepsiCo sponsored the American version of Cowell's The X Factor in hopes of not repeating its Idol mistake until its cancellation.[230]

American Idol tour

The top ten (eleven in season ten) toured at the end of every season. In the season twelve tour a semi-finalist who won a sing-off was also added to the tour. Kellogg's Pop-Tarts was the sponsor for the first seven seasons, and Guitar Hero was added for the season seven tour. M&M's Pretzel Chocolate Candies was a sponsor of the season nine tour. The season five tour was the most successful tour with gross of over $35 million.[231]

Music releases

American Idol has traditionally released studio recordings of contestants' performances as well as the winner's coronation single for sale. For the first five seasons, the recordings were released as a compilation album at the end of the season. All five of these albums reached the top ten in Billboard 200 which made then American Idol the most successful soundtrack franchise of any motion picture or television program.[232] Starting late in season five, individual performances were released during the season as digital downloads, initially from the American Idol official website only. In season seven the live performances and studio recordings were made available during the season from iTunes when it joined as a sponsor. In Season ten the weekly studio recordings were also released as compilation digital album straight after performance night.

19 Recordings, a recording label owned by 19 Entertainment, currently hold the rights to phonographic material recorded by all the contestants. 19 originally partnered with Bertelsmann Music Group (BMG) to promote and distribute the recordings through its labels RCA Records, Arista Records, J Records, Jive Records. In 2005-2007, BMG partnered with Sony Music Entertainment to form a joint venture known as Sony BMG Music Entertainment. From 2008-2010, Sony Music handled the distribution following their acquisition of BMG. Sony Music was partnered with American Idol and distribute its music, and In 2010, Sony was replaced by as the music label for American Idol by UMG's Interscope-Geffen-A&M Records.[233]

Tie-ins

American Idol video games

- American Idol – PlayStation 2, PC, Game Boy Advance, mobile phone

- Karaoke Revolution Presents American Idol – PlayStation 2, Xbox 360

- Karaoke Revolution Presents American Idol Encore – PlayStation 2, PlayStation 3, Wii, Xbox 360

- Karaoke Revolution Presents American Idol Encore 2 – PlayStation 3, Wii, Xbox 360

- Idol 011 – Wii, Xbox 360

Theme park attraction

On February 14, 2009, The Walt Disney Company debuted "The American Idol Experience" at its Disney's Hollywood Studios theme park at the Walt Disney World Resort in Florida. In this live production, co-produced by 19 Entertainment, park guests choose from a list of songs and audition privately for Disney cast members. Those selected then perform on a stage in a 1000-seat theater replicating the Idol set. Three judges, whose mannerisms and style mimic those of the real Idol judges, critique the performances.[234] Audience members then vote for their favorite. There are several preliminary-round shows during the day that culminate in a "finals" show in the evening where one of the winners of previous rounds that day is selected as the overall winner.[235] The winner of the finals show receives a "Dream Ticket" that grants them front-of-the-line privileges at any American Idol audition.[234] The attraction closed on August 30, 2014.[236]

Other broadcasts

American Idol is broadcast to over 100 nations outside of the United States.[237] In most nations these are not live broadcasts and may be tape delayed by several days or weeks. In Canada, the first thirteen seasons of American Idol were aired live by CTV and/or CTV Two, in simulcast with Fox. CTV dropped Idol after its thirteenth season and in August 2014, Yes TV announced that it had picked up Canadian rights to American Idol beginning in its 2015 season.[238][239]