American Federation of Teachers

.png) | |

| Full name | American Federation of Teachers |

|---|---|

| Founded | April 15, 1916 |

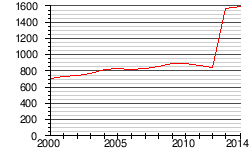

| Members | 1,597,140 (2014)[1] |

| Affiliation | AFL-CIO, EI |

| Key people | Randi Weingarten, President |

| Office location | Washington, D.C. |

| Country | United States |

| Website |

www |

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) is an American labor union that primarily represents teachers. Originally called the American Federation of Teachers and Students, the group was founded in 1900.[2][3] AFT periodically developed additional sub-groups for paraprofessionals and school-related personnel; local, state and federal employees; higher education faculty and staff, and nurses and other healthcare professionals within the organization. The AFT's affiliations include the trade union federation since its founding, the old American Federation of Labor until 1955, and the AFL-CIO.

Membership

At first, many teachers rejected the AFT's assertion that teachers should join unions. The dispute led to a slow member growth rate that lasted for 50 years. The legal and political climate discouraged collective bargaining in education. School boards mounted a campaign against the AFT, pressuring and intimidating teachers to resign from the union. By the end of the 1920s, AFT membership had dropped to fewer than 5,000—about half the membership of 1920."[5] In 1960, the AFT had an estimated 65,000 members. Almost overnight, the AFT's membership swelled by 30 percent due to UFT protests organized by Albert Shanker and Charles Cogen. In 1964, the Industrial Union Department of the AFL-CIO pledged to match dollar-for-dollar the expenditure of AFT funds to organize teachers. But, by the end of the decade the union had swelled to more than 400,000 members. By 2000, the union had 1.1 million members. In July 2010, the AFT was the second-largest education labor union in the United States. AFT represented an estimated 1.5 million members which included 250,000 retirees.[4]

The National Education Association (NEA) is the largest US education trade union with an estimated 3.2 million-members.[6] The NEA rejected a merger with the AFT at their annual meeting in 1998.

AFT presidents

Albert Shanker

In 1964, Albert Shanker was elected president of the UFT. He was the President of AFT until his passing of bladder cancer on February 22, 1997. Shanker published a column entitled, "Where We Stand" in the New York Times as a paid advertisement on December 13, 1970.[7] At that time, Shanker believed it was the best way to share the union's policy from what he considered "filtering and interference of the press." His activism continued throughout the course of his career and included several notable accomplishments.

Ocean Hill–Brownsville strike

On May 8, 1968 the union held a one-day strike in the Ocean Hill–Brownsville school district. The city of New York established the Ocean Hill-Brownsville area of Brooklyn as one of three decentralized school districts in 1968 in an effort to give the minority community more say in school affairs. The school district operated under a separate, community-elected governing board with the power to hire administrators.

The experiment had the early support of the UFT. But the UFT also argued that the new school district should retain its most experienced teachers in the schools.

The crisis began when the governing board fired 13 teachers and six administrators for what the board said were efforts to sabotage the decentralization experiment. Under the terms of the decentralization agreement, the teachers were returned to the control of the New York City public school system, where they sat idle in the school district offices.

UFT president Albert Shanker demanded due process. He declared that the UFT would not be passive while teachers were removed without specific charges being filed and without a chance to defend themselves.

Many observers argued that the decentralization experiment was a canard. Little educational advancement for the poverty-stricken students of Ocean Hill-Brownsville could be achieved without additional resources, which were not provided. But worried, angry parents who saw their children failing in school saw decentralization as something different—and 'different' was better than the existing, failing school system.

There was a protracted dispute between those in the community who supported the Ocean Hill-Brownsville board and those supported UFT's argument that the teachers were denied their rights illegally.

Shanker was jailed for 15 days on February 3, 1969, for sanctioning the Ocean Hill-Brownsville strikes.

But the UFT prevailed. The teachers were re-instated and an agreement worked out reaffirming due process rights for New York City educators.

The Ocean-Hill Brownsville strike deeply affected the AFT. While the union formally recommitted itself to militancy, the AFT slowly began adopting a more moderate stand. Although AFT president David Selden would be arrested on February 23, 1970, during the Newark, New Jersey teachers' strike, becoming the third union president to go to jail, Selden's prison term would mark the last major AFT strike.

UFT

After the anti-communist purge in 1941, the Teachers Guild remained the sole AFT affiliate in New York City. In 1960, New York City social studies teacher Albert Shanker and Teachers Guild president Charles Cogen led New York City teachers out on strike. At the time, there were more than 106 teacher unions in the New York City public schools – many existing solely on paper with no real membership or organization. At the same time other unions flourished such as the Brooklyn Teachers Association.

The motives behind the strike were wages, establishment of a grievance process, reduced workloads and more funding for public education. But in order to win on these issues, Shanker and Cogen argued, the city's teachers had to be in one union. In early 1960, the Teachers Guild merged with a splinter group from the more militant High School Teachers Association to form the United Federation of Teachers or 'UFT'.

The UFT struck on November 7, 1960. More than 5,600 teachers walked the picket line, while another 2,000 engaged in a sick-out. It was a fraction of the city's 45,000 teachers. But intervention by national, state and local AFL-CIO leaders pressured New York City mayor Robert Wagner Jr. to appoint a pro-labor fact-finding committee to investigate conditions in the city's schools and recommend a solution to the labor problem.

The fact-finding committee recommended a collective bargaining law, which eventually was forced onto the city's Board of Education by the state of New York. Despite political infighting with the NEA, an infusion of cash by the national AFT and the AFL-CIO enabled the UFT to win the December 16, 1961, election with 61.8 percent of the votes.

In 1967, the UFT held a three-week strike for smaller class sizes. Shanker was jailed in the Sing-Sing state prison for 15 days for violating the Taylor Law's prohibition on public employee strikes. On March 30, 1972, Shanker engineered a merger between the AFT and NEA affiliates in New York state to create the New York State United Teachers (NYSUT). On October 20, 1973 Albert Shanker—still only president of the UFT—was elected to AFL-CIO executive council. In 1974, Shanker defeated Selden for the presidency of the AFT after a bitter election contest. The same year, the AFT and NEA affiliates in Florida merged to form FEA-United. In 1975, the UFT persuaded the New York State Teachers Retirement Fund to loan $150 million to New York City to prevent the city's bankruptcy.

As the 1970s drew to a close, the AFT's dwindling militancy led the union to turn inward. Organizing continued, with the AFT winning the right to represent faculty at the State University of New York (SUNY) system in 1978. While the union added about 200,000 members each decade, the 1990s witnesses a slowdown in organizing which accelerated in the new millennium. Shanker pressed for merger with the NEA, but merger seemed to be less and less likely. By the 1990s, merger was no longer one of Shanker's priorities.

The release in 1983 of the United States Department of Education's 'A Nation at Risk,' a report highly critical of the US education system, helped to cement the changes occurring in the AFT. Strong curriculum standards and professional development consumed the union's attention and resources. In 1995, the AFT undertook its own campaign to accomplish the goals of 'A Nation at Risk.' Titled 'Responsibilities, Respect, Results: Lessons for Life,' the campaign sought state legislation to strengthen curriculum and graduation standards; stronger disciplinary standards in classrooms, accompanied by new funding for the education of unruly students and to achieve smaller class sizes; and a new national emphasis on civic education, to strengthen democratic ideals. While praised, the campaign was not well-implemented by AFT affiliates and few successes were achieved.

Sandra Feldman

Sandra Feldman, Shanker's protege and president of the UFT, was elected AFT president in July 1998. Feldman was the first woman to serve as AFT's president since 1930, and was elected to the AFL-CIO executive council. During her presidency, AFT attempted to expand its organizing capacity, build state-level capacity to service existing units and organize new ones, and work with the John Sweeney administration at the AFL-CIO to reinvigorate the labor movement.[8] In many ways, Feldman saw her presidency as one in which the legacy of Al Shanker would be implemented after his untimely death.

But Feldman was hampered by a lack of internal resources and a unified executive council whose allegiance was to Albert Shanker rather than her. Popular with members and advocating a new vision for the union, nevertheless Feldman struggled to overcome the AFT's institutional inertia. Feldman brought a new focus on educational issues to the AFT.

Feldman's relationship with the AFL-CIO was difficult to characterize. The AFT had opposed the election of John Sweeney as AFL-CIO president in 1995. But Feldman supported Sweeney's efforts to encourage new organizing and restructure the umbrella group. Yet Feldman was deeply critical of the Sweeney administration's interference in the internal politics of the Teamsters union. Feldman's position on the AFL-CIO executive council was strengthened in December 2001 when AFT secretary-treasurer Edward J. McElroy was elected to the body.

In early 2003, Sandra Feldman was diagnosed with breast cancer. After treatment, she resumed her duties in December 2003. A recurrence of the cancer in the spring of 2004 led Feldman to announce her retirement at the biennial AFT convention in July 2004. Sandra Feldman died September 18, 2005.

Edward J. McElroy

Edward J. McElroy, the AFT's secretary-treasurer since 1992, was elected president of the AFT to replace Feldman. McElroy's emphasis as president has been on the union basics such as external and internal organizing, collective bargaining, and political and legislative activity. McElroy was a strong supporter of John Sweeney during the 2004–05 debates over the future of the AFL-CIO, while acknowledging that SEIU president Andy Stern was correct in critiquing the AFL-CIO's organizing and servicing efforts.

On February 12, 2008, McElroy announced he would retire at the union's regularly scheduled biennial convention in July. On July 14, 2008, Randi Weingarten was elected to succeed him. Weingarten served for 12 years—from 1997 to 2009—as president of the United Federation of Teachers.[9]

Political activities

In 2008, AFT provided a campaign contribution of $1,784,808.59 to Hillary Rodham Clinton. AFT also awarded Barack Obama with a contribution of $1,997,375.00 that same year.[10]

Civil rights activities

Racial tension

The AFT was one of the first trade unions to allow African-Americans and minorities to become full members of their trade union.[11] In 1918, the AFT called for equal pay for African-American teachers, the election of African Americans to local school boards and compulsory school attendance for African-American children. In 1919, the AFT demanded equal educational opportunities for African-American children, and in 1928 called for the social, political, economic, and cultural contributions of African Americans to be taught in the public schools.[12]

In 1941 under pressure from the AFL, the union ejected Local 5 (New York City), Local 537 (the City College of New York), and Local 192 (Philadelphia) for being communist-dominated. The charter revocations represented nearly a third of the union's national membership.

In 1936 teachers in Butte, Montana, negotiated the first AFT collective bargaining agreement. In 1948 the union stopped chartering segregated locals. It filed an amicus brief in the historic 1954 US Supreme Court desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education. On December 10, 1956, Local 89 in Atlanta, Georgia, left the AFT because it would not comply with the AFT directive that all locals integrate. In 1957, the AFT expelled all locals that refused to desegregate.

In 1963, the AFT (unlike many other unions) actively supported the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom organized by civil rights leaders, at which Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. Busloads of AFT members came to the nation's capital for the event.

In 1965, the UFT put its funds in a bank that refused to have dealings with the apartheid regime in South Africa—20 years before most other unions began to campaign against apartheid.

However, a series of strikes ensued between September 9 and November 17, 1968. Many supporters of the local school board resorted to racial invective. Shanker was routinely branded a racist, and many African-Americans accused the UFT of being 'Jewish-dominated'.

Collective bargaining

Throughout this period, the union also struggled over the issue of militancy. Margaret Haley, an early AFT leader, said that they had realized that they "had to fight the devil with fire".[13] But Haley's view was not shared by a majority of AFT members in the union's first decades. Like many unions of the era, the AFT relied heavily on making a statistical case for its wage and benefit proposals and then consulting with the school board rather than utilizing the power of collective action.

By the late 1940s, AFT was slowly moving toward collective bargaining as an official policy. The St. Paul Federation of Teachers struck on November 25, 1946. It was the first AFT local to ever strike. The local settled on January 1, 1947 after 38 days on the picket line. Nearly a decade later, the union held—and won—its first collective bargaining election in East St. Louis, Illinois, on December 10, 1956. The vote tally was AFT-226, NEA-201. Robert G. Porter was treasurer of the East St. Louis Federation of Teachers at the time of the election and later went on to become the longest serving secretary-treasurer in the history of the national AFT. In 1963, the AFT convention voted to end the union's no-strike policy.

In 1967, the New York State Legislature passed the Taylor Law, which provided collective bargaining rights to public employees (but prohibiting them to strike). The AFT began rapidly organizing new members in New York state. Nearby states such as Rhode Island, Connecticut, Pennsylvania and New Jersey also saw large membership increases.

Controversies

AFT statement on shared governance in higher education

In 2002, the Higher Education Program and Policy Council of the American Federation of Teachers also published a statement on shared governance. The policy statement is a response to the fact that many governing boards have adopted the "mantra of business” (American Federation of Teachers 2002). The AFT (2002: 5) iterates purpose by which higher education achieves democratic organizational processes between administration and faculty, believing shared governance is under attack in six ways: (1) The outsourcing of instruction, particularly to learning technologies; (2) Redirecting teaching to part-time and temporary faculty; (3) Re-orienting curriculum to business oriented coursework; (4) The buying and selling of courseware for commercial exploitation; (5) For profit teaching and research; (6) Through the formation of a “commercial consortia with other universities and private investors."

Steve Jobs opposition to teacher's unions

In a meeting with US President Barack Obama in October 2010, Apple Inc. CEO Steve Jobs said that the work rules of teacher's unions were crippling America's education system. To improve the nation's educational outcomes Jobs recommended giving principals the power to hire and fire teachers based on merit, increasing the length of each school day and of each school year, and using interactive teaching technologies in schoolrooms that would provide personalized feedback to students.[14]

Media

Film

In 2010, four American film documentaries, most notably Waiting for Superman, portrayed the AFT as hurting children by opposing charter schools and protecting incompetent teachers.[15]

Literature

American Educator

AFT publishes a quarterly magazine for teachers covering various issues about children and education called American Educator. In mid-2009, AFT estimated its total circulation at over 900,000.[16]

AFT members

- J. Quinn Brisben, writer and activist

- Ralph Bunche, former United Nations Under-Secretary-General and Nobel Peace Prize winner

- Tony Danza, film and television actor

- Paul Douglas, US Senator from Illinois

- John Dewey, educator

- Albert Einstein, scientist

- Michael Harrington, political activist

- Hubert Humphrey, US vice-president and US Senator from Minnesota

- Mike Mansfield, former United States Senate Majority Leader and US Ambassador to Japan

- Frank McCourt, Pulitzer Prize-winning author

- Robert Oppenheimer, scientist[17]

- Donna Shalala, former United States Secretary of Health and Human Services

- Elie Wiesel, Nobel Peace Prize winner

Notes

- ↑ US Department of Labor, Office of Labor-Management Standards. File number 000-012. Report submitted October 7, 2014.

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=ePgBAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA531

- ↑ http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F20F13FD355811738DDDA10894DC405B808CF1D3

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 US Department of Labor, Office of Labor-Management Standards. File number 000-012. (Search)

- ↑ "History (July 2004)". American Federation of Teachers. Archived from the original on June 14, 2006. Retrieved 2006-06-18.

- ↑ Hornick-Lockard, Barbara. "Teacher's Unions - Past and Present.". Research Starters Education (Online Edition).

- ↑ "Remembering Albert Shanker: A Pivotal Figure in AFT History.". American Teacher 91.5 (2007): 9.

- ↑ "Interview with Sandra Feldman.". Association for Career & Technical Education (1998) 73.

- ↑ Green, Elizabeth (July 14, 2008). "Obama Tells Teachers Union He Opposes Vouchers". New York Sun. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ http://www.fec.gov/press/press2008/2008indexp/2008iebycommittee.pdf

- ↑ Dewing, Rolland. "The American Federation of Teachers and Desegregation.". Journal of Negro Education 42.1 (1973): 79-92.

- ↑ Eaton, The American Federation of Teachers, 1916–1961, 1975, p. 61-72.

- ↑ Haley, Margaret (1982). Battleground: the autobiography of Margaret Haley (edited by Robert L. Reid). Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- ↑ Isaacson, Walter (2011), Steve Jobs, Simon & Schuster, pp. 544–45, ISBN 9781451648539

- ↑ Richard Whitmire, The bee eater: Michelle Rhee takes on the nation's worst school district (2011) p. 126. John Wiley and Sons, 2011 ISBN 0-470-90529-8, ISBN 978-0-470-90529-6

- ↑ "American Educator". American Federation of Teachers Main Website. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- ↑ Herken, Brotherhood of the Bomb: The Tangled Lives and Loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller, 2002, p. 30.

References

- American Federation of Teachers. "Shared Governance in Colleges and Universities." Policy statement. 2002. Retrieved September 27, 2006.

- Archives of Labor History. Wayne State University. An American Federation of Teachers Bibliography. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-8143-1659-X

- Berube, Maurice R. Teacher Politics: The Influence of Unions, Vol. 26. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1988. ISBN 0-313-25685-3

- Braun, Robert J. Teachers and Power: The Story of the American Federation of Teachers. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1972. ISBN 0-671-21167-6

- Cain, Timothy Reese. "For Education and Employment: The American Federation of Teachers and Academic Freedom, 1926–1941." History of Higher Education Annual, 26 (2007), 67–102.

- Dewing, Rolland. "The American Federation of Teachers and Desegregation," Journal of Negro Education Vol. 42, No. 1 (Winter, 1973), pp. 79–92 in JSTOR

- Eaton, William Edward. The American Federation of Teachers, 1916–1961: A History of the Movement. Urbana, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1975. ISBN 0-8093-0708-1

- Gaffney, Dennis. Teachers United: The Rise of New York State United Teachers. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 2007. ISBN 0-7914-7191-8

- Gordon, Jane Anna. Why They Couldn't Wait: A Critique of the Black-Jewish Conflict Over Community Control in Ocean-Hill Brownsville, 1967–1971. Oxford: RoutledgeFalmer, 2001. ISBN 0-415-92910-5

- Haley, Margaret. Battleground: The Autobiography of Margaret A. Haley. Robert L. Reid, ed. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1982. ISBN 0-252-00913-4

- Moe, Terry M. Special Interest: Teachers Unions and America's Public Schools (Brookings Institution Press; 2011) 513 pages; argues that teachers' unions cause serious problems with education in the US and contribute to the slowness of reform.

- Murphy, Marjorie. Blackboard Unions: The AFT and the NEA, 1900–1980. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-8014-2365-1

- O'Connor, Paula. "Grade School Teachers Become Labor Leaders." Labor's Heritage. 7:2 (Fall 1995).

- Podair, Jerald. The Strike That Changed New York: Blacks, Whites, and the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Crisis. Princeton, NJ: Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-300-08122-7

- Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. AFT Historical Timeline. No date. Accessed June 18, 2006.

- Knudsen, Andrew. Communism, Anti-Communism, and Faculty Unionization: The American Federation of Teachers Union at the University of Washington, 1935–1948, Great Depression in Washington State Project, 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to American Federation of Teachers. |

- Official website

- Campaign for Children's Health Care

- The Washington State Teacher (1945–1951), from The Labor Press Project

Archives

- AFT official archives. Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. Detroit, Michigan

- American Federation of Teachers Local 200 Records. 1951-1979. 11.05 cubic feet.

- American Federation of Teachers Local 200 Photograph Collection. circa 1970-1974. 69 photographic prints (1 box) ; various sizes, 12 negatives.

- American Federation of Teachers, Local 336 Records. 1948-1978. 0.42 cubic feet.

- American Federation of Teachers Local 772 Records. 1963-1982. 1.14 cubic feet.

- American Federation of Teachers Local 401 Records. 1 volume plus approximately 214 items.

- Washington State Federation of Teachers Records. 1937-2006. 22.39 cubic feet.

- American Federation of Teachers, Yakima Local 1485 Records. 1969-1997. 12 cubic feet.

- AFT Antecedents to Historical Reform, a digital library project to host primary resources from the AFT historical collections in the Walter P. Reuther Library that document various education reform initiatives that union and school boards have collaborated on from 1983 to present.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||