Amasra

| Amasra | |

|---|---|

| |

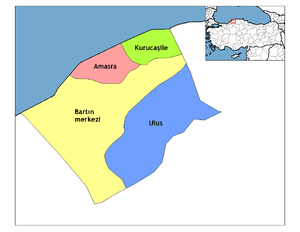

Amasra Location in Turkey | |

| Coordinates: 41°44′58″N 32°23′11″E / 41.74944°N 32.38639°E | |

| Country |

|

| Region | Black Sea |

| Province | Bartın |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mehmet Emin Timur (CHP) |

| Area[1] | |

| • District | 178.82 km2 (69.04 sq mi) |

| Population (2012)[2] | |

| • Urban | 6,601 |

| • District | 15,284 |

| • District density | 85/km2 (220/sq mi) |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| • Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) |

| Postal code | 74XXX |

| Area code(s) | (+90) 378 |

| Climate | Cfb |

Amasra (from Greek Amastris Ἄμαστρις, gen. Ἀμάστριδος) is a small Black Sea port town in the Bartın Province, Turkey. The town is today much appreciated for its beaches and natural setting, which has made tourism the most important activity for its inhabitants. In 2010 the population was 6,500.

Amasra has two islands: the bigger one is called Büyük ada (Great Island) while the smaller one is called Tavşan adası (Rabbit Island).

History

Situated in the ancient region of Paphlagonia, the original city seems to have been called Sesamus (Greek: Σήσαμος), and it is mentioned by Homer[3] in conjunction with Cytorus. Stephanus[4] says that it was originally called Cromna; but in another place,[5] where he repeats the statement, he adds, as it is said; but some say that Cromna is a small place in the territory of Amastris, which is the true account. The place derived its name Amastris from Amastris, the niece of the last Persian king Darius III, who was the wife of Dionysius, tyrant of Heraclea, and after his death the wife of Lysimachus. Four small Ionian colonies, Sesamus, Cytorus, Cromna, also mentioned in the Iliad,[6] and Tium, were combined by Amastris, after her separation from Lysimachus,[7] to form the new community of Amastris, placed on a small river of the same name and occupying a peninsula.[8] According to Strabo, Tium soon detached itself from the community, but the rest kept together, and Sesamus was the acropolis of Amastris. From this it appears that Amastris was really a confederation or union of three places, and that Sesamus was the name of the city on the peninsula. This may explain the fact that Mela[9] mentions Sesamus and Cromna as cities of Paphlagonia, while omitting Amastris.[10]

The territory of Amastris produced a great quantity of boxwood, which grew on Mount Cytorus. Its tyrant Eumenes presented the city of Amastris to Ariobarzanes of Pontus in c. 265–260 BC rather than submit it to domination by Heraclea, and it remained in the Pontic kingdom until its capture by Lucius Lucullus in 70 BC in the second Mithridatic War.[11] The younger Pliny, when he was governor of Bithynia and Pontus, describes Amastris, in a letter to Trajan,[12] as a handsome city, with a very long open place (platea), on one side of which extended what was called a river, but in fact was a filthy, pestilent, open drain. Pliny obtained the emperor's permission to cover over this sewer. On a coin of the time of Trajan, Amastris has the title Metropolis. It continued to be a town of some note to the seventh century of our era. From Amasra got its name an important place of Constantinople, the Amastrianum.

The city was not abandoned in the Byzantine Era, when the acropolis was transformed into a fortress and the still surviving church was built. It was sacked by the Rus during the First Russo-Byzantine War in the 830s. Speros Vryonis states that in the 9th century a "combination of local industry, trade, and the produce of its soil made Amastris one of the more prosperous towns on the Black Sea."[13] In the 13th century Amasra exchanged hands several times, first becoming a possession of the Empire of Trebizond in 1204,[14] then at some point in the next ten years being captured by the Seljuk Turks, until finally in 1261, in her bid to monopolize the Black Sea trade, the town came under the control of the Republic of Genoa. Genoese domination ended when the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II conquered the whole Anatolian shores of the Black Sea.[15]

The bishopric of Amastris was established early: according to Eusebius, its congregation received a letter from the second-century bishop, Dionysius, Bishop of Corinth, wherein he names their bishop, one Palmas.[16] The see was initially a suffragan of the metropolitan of Gangra, capital of the Roman province of Paphlagonia, but in the late 8th century its bishop obtained from the Byzantine Emperor its elevation to the rank of autocephalous archeparchy. It is listed as such in the Notitia Episcopatuum attributed to Basil the Armenian (c. 840) and in that of Leo VI the Wise (early 10th century). In the middle of the 10th century it obtained the rank of metropolitan see without suffragans, a rank it held until, due to the diminution in the number of Christians in the area, it was suppressed. From the 14th century to the second half of the 15th, the town was also the seat of a bishopric of the Latin Church.[17][18][19] No longer a residential bishopric, Amastris is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[20]

Main sights

With its architectural heritage, Amasra is a member of the Norwich-based European Association of Historic Towns and Regions.[21]

Archaeological Museum: there is a fine medium-sized archaeological museum by the sea with remains from both land and underwater. Of particular interest is a statue of the snake god Glykon, a fraudulent creation of a local entrepreneur during Roman imperial times.

Amasra Castle

Amasra Castle was built during the Roman period. The walls of the castle were built by the Byzantines. The front walls and gates were built by the Genoese in the 14th and 15th centuries.[22] Though located on a narrow peninsula, a tunnel under the castle leads to a fresh water pool.

Church Mosque

Built as a Byzantine church in the 9th century AD. The church is a small chapel and its narthex section consists of three parts. After Fatih Sultan Mehmet conquered Amasra in 1460, it was converted to a mosque. The church mosque was closed to prayer in 1930.[22]

Bird's Rock Road Monument

Bird's Rock Road Monument was created between AD 41-54 by order of Bithynia et Pontus Governor Gaius Julius Aquila. It was a resting place and monument. At the time when Claudius was Rome's Emperor, Aguila was the commander of the building army in the eastern provinces.[22] It is located a little outside Amasra on the road in, it is easily accessed by steps leading from the roadside.

Power Station

In 2009 a coal-fired power station of 2640 MWe (or 1200 MWe) was proposed.[23] It will have a super critical boiler, will utilise a nearby bituminous coal mine and is to be seawater cooled. An application has been made to acquire 49-year long-term concession rights for exploitation of local bituminous proven coal reserves of approximately 573 million metric tons.[24] Concerns have been raised about the effect on air quality,[25] marine ecology [26] and ash [27]

References

- ↑ "Area of regions (including lakes), km²". Regional Statistics Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2002. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- ↑ "Population of province/district centers and towns/villages by districts - 2012". Address Based Population Registration System (ABPRS) Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad, ii. 853

- ↑ Stephanus, Ethnica, s.v. "Amastris"

- ↑ Stephanus, Ethnica, s.v. "Cromna"

- ↑ Homer, ii. 855

- ↑ Memnon, History of Heraclea, 5, 9

- ↑ Strabo, Geography, xii. 3

- ↑ Pomponius Mela, De chorographia, i. 93

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History, vi. 2

- ↑ Appian, The Foreign Wars, "The Mithridatic Wars", 82

- ↑ Pliny the Younger, Letters, x. 99

- ↑ Vryonis, The decline of medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor: and the process of Islamization from the eleventh through the fifteenth century, (Berkeley: University of California, 1971), p. 14

- ↑ Anthony Bryer, "David Komnenos and Saint Eleutherios", Archeion Pontou, 42 (1988-1989), p. 179

- ↑ Franz Babinger dates the conquest to autumn of 1460, although Halil İnalcık would date its capture to A.H. 863 (AD 1458/1459). Babinger, Mehmed the Conqueror and his Time (Princeton: University Press, 1978), p. 181 and note.

- ↑ Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica, 4.23

- ↑ Michel Lequien, Oriens christianus in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus, Paris 1740, Vol. I, coll. 561-566

- ↑ Jean Richard, La Papauté et les missions d'Orient au Moyen Age (XIII-XV siècles), École Française de Rome, 1977, pp. 236 and 246

- ↑ Siméon Vailhé, v. Amastris, in Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie ecclésiastiques, vol. XII, Paris 1953, coll. 971-973

- ↑ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 830

- ↑ "Turkey". European Association of Historic Towns and Regions. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Local signage

- ↑ http://www.hemaenerji.com/en/home/about_company.asp

- ↑ http://www.turkishweekly.net/columnist/3261/new-thermal-power-plant-investment-in-amasra-county-of-bartin-province.html

- ↑ http://energynewsletterturkey.blogspot.com/2010/04/on-amasra-new-thermal-power-plant.html

- ↑ http://energynewsletterturkey.blogspot.com/2009/12/new-thermal-power-plant-investment.html

- ↑ http://www.amasra.biz/haber/221-haberler-amasra39yi-seviyorumtermik-santral-istemiyorum.html

Sources

- "Amastris" from the Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)

- Richard Stillwell, William L. MacDonald, Marian Holland McAllister (editors); The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, "Amastris", Princeton, (1976)

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Amastris". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Amastris". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amasra. |